MAG / Shutterstock.com

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are among the most high-risk medicines prescribed in primary care. By suppressing the immune response to inflammation in autoimmune and related conditions, they increase susceptibility to infections, which tend to be more severe. In addition, some of the drugs are directly hepatotoxic.

DMARDs are typically initiated by a specialist in secondary care, sometimes under a shared care guideline, with responsibility for subsequent prescribing and monitoring then passed to GPs. Patients on these drugs need regular blood tests to ensure that the treatment is not doing more harm than good. Following titration, the frequency of monitoring will usually reduce.

In early 2020, I investigated two significant events involving DMARDs at one of the practices I work in. In one — an example of poor transfer of care — a patient had been started on tacrolimus without any ongoing monitoring having been arranged. In the other, a patient established on leflunomide had not attended for monitoring for several months, but prescriptions were still being issued. Thankfully, neither patient came to harm.

A concurrent review of all patients’ monitoring frequencies in response to the COVID-19 emergency, which led to a national attempt to reduce face-to-face contact in general practice, demonstrated that we could not swiftly determine each patient’s current monitoring frequency. The practice clearly needed more robust procedures and awareness around DMARD monitoring.

I led the project, with substantial input from our primary care network (PCN) pharmacists and the practice’s prescribing lead GP. Everyone supported the project because its safety implications were clearly understood and good communication with both the clinical and administrative teams throughout enabled its smooth implementation.

Our approach involved developing clear standard operating procedures (SOPs) and batch reports (bespoke searches arranged to automatically run at specified intervals) — in our case, using the clinical system TPP SystmOne.

We introduced a SOP for initiating DMARDs to standardise the workflow. The SOP states that the clinician processing the letter from the specialist should arrange the first few blood test appointments at the time of processing the letter (the administrative task of booking is delegated to the reception team). Thus, the patient becomes used to attending for regular monitoring from the outset.

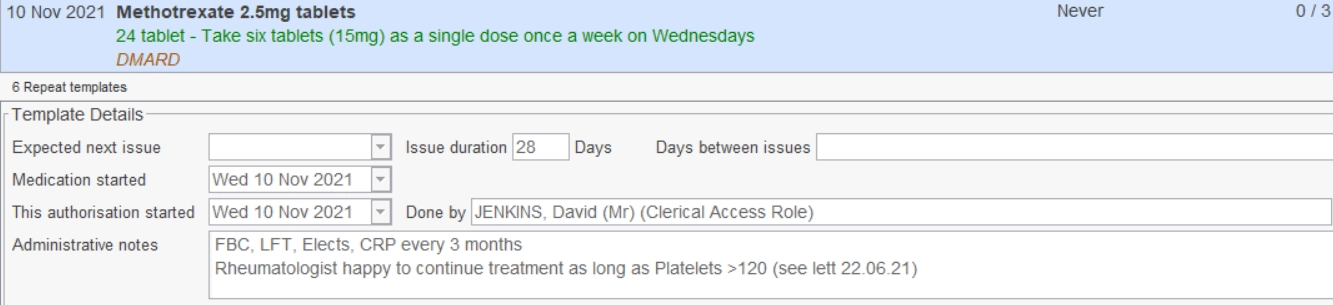

Previously it was not easy for non-clinicians to even identify a DMARD, let alone the patient’s current monitoring frequency. To rectify this issue, we now label the drug on the medicines screen as DMARD (see Figure 1) by an automated process, and the current blood test frequency is also annotated manually.

Note: 1. Drug clearly labelled as DMARD;

2. Authorised only for three issues (until next monitoring is due);

3. Frequency of blood tests clearly identifiable;

4. Comment regarding an out-of-range result that has previously been addressed.

The prescription clerk’s SOP was also rewritten. For each DMARD request, whether or not the medicine has been authorised for issue by a GP, the clerk checks that monitoring has been conducted within the specified period and, if so, that blood test results were filed as normal. If either of these criteria is not met, the GP is provided with relevant information to confirm that the medicine may be issued.

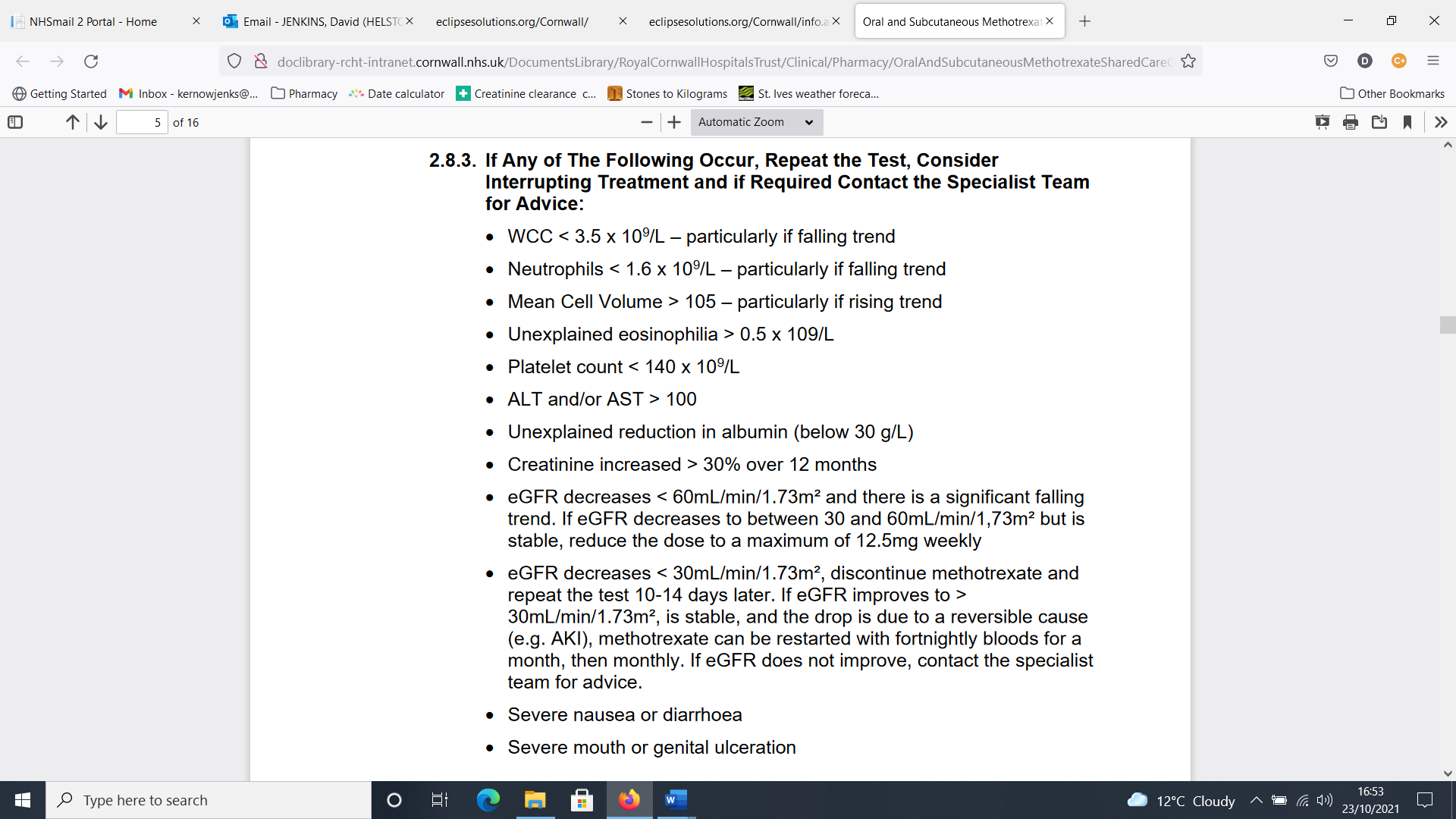

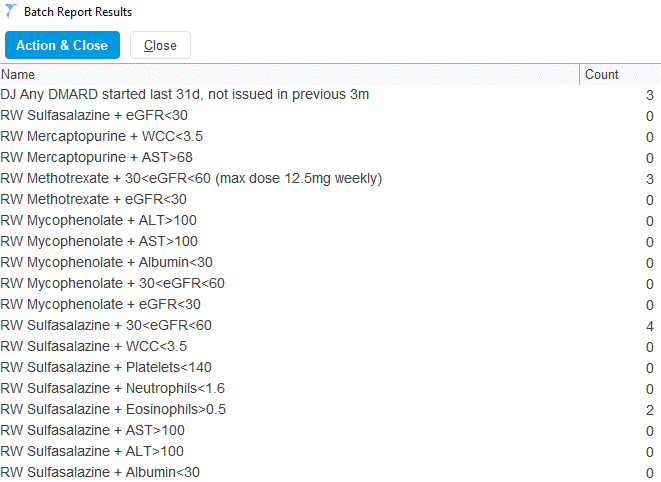

Given the large amount of monitoring advice to consider (see Figure 2), it is not surprising that overloaded clinicians, still filing lab results at 8pm, may sometimes miss important out-of-range blood test results in relation to DMARDs. Computers, on the other hand, never tire and we developed an array of reports that automatically run monthly. When the results are received (see Figure 3), the pharmacy team processes them, with an SOP to guide them. These searches find:

- Patients started (or restarted) on a DMARD in the past month (as an additional safety net to the initiation procedure above);

- Patients whose monitoring results are outside acceptable range;

- Patients whose most recent monitoring is not within the past 12 weeks.

The project has been considered a success, particularly by our GPs who are reassured that if they miss a blood test outlier, it will be captured. Awareness of DMARDs has also been raised among non-clinicians; chiefly prescription clerks, but also the reception team. A useful phrase to use when training non-clinicians is: “When you see DMARD, think ‘D for Danger — first and last!’”

Our approach has been shared with the other PCN practices and they have incorporated some aspects, especially batch reports and the welcome reassurance they bring.

The work continues; our processes are continuously being refined. If a patient has been found to have slipped through the net, we establish which procedure failed and whether it can be improved further. My two guiding principles are that only by being brutally honest about our systems’ failings can we really improve anything, and that we rarely do anything as well as we think we do.

The next step in the project is to ensure that we are capturing all patients within the PCN prescribed biologics elsewhere,for whom we have been asked to conduct monitoring. Does anyone know whether all monoclonal antibody treatments (including those for respiratory indications) need “DMARD bloods”? We would love to know…

David Jenkins is a pharmacist working in Helston, Cornwall

You may also be interested in

Coroner flags lack of clarity around expanded role of community pharmacists under Pharmacy First

Patient safety commissioner to approach PM over ‘disappointing’ delay to valproate compensation