Shutterstock.com

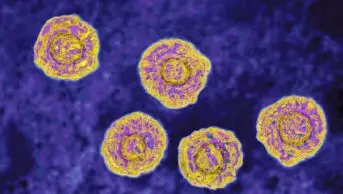

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne virus that affects the liver. If left untreated, it can, over time, lead to complications, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition to these direct health consequences, the stigma attached can lead to patients feeling ashamed. The World Health Organization has set a target to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health threat by 2030.

Hepatitis C was historically treated with peginterferon and ribavirin. Treatment could take up to 11 months, had many side effects, and required close monitoring so was always administered via secondary care clinics. When newer direct-acting antivirals came on to the market, they cut treatment times to 8–12 weeks and increased the cure rate to more than 95%. The all-oral regimens and greatly improved side-effect profile meant that far less monitoring was required, so treatment pathways could be modified.

In the UK, hepatitis C is most prevalent among people who inject drugs, but these are often seen as “hard to reach” patients who do not attend hospital appointments. This may be because they:

- are experiencing homelessness and do not receive their appointment letters;

- cannot afford/manage travel to a hospital;

- have previously felt judged by healthcare professionals;

- require additional support.

After multiple missed appointments, these patients are discharged from hospital waiting lists; therefore, missing the opportunity to be treated and leading to an increased risk of complications for themselves and onward transmission to others. We wanted to change this and find a way to treat patients in a manner that worked for them.

We were able to inform patients whether they had hepatitis C within one hour

In 2019, we set up a pilot project in Wrexham, North Wales, to treat hepatitis C in the community by developing an accelerated treatment pathway. The pathway was aimed at people with hepatitis C experiencing homelessness or those who are vulnerably housed. We gained access to a weekly drop-in session at a Salvation Army church in Wrexham. They provided food and had multiple providers present, such as GPs, probation services and housing. As a prescribing pharmacist, I, together with a colleague, worked alongside a blood-borne virus nurse from the health board’s harm reduction team. A grant from the pharmaceutical company Gilead enabled us to hire a rapid point-of-care testing machine and we were able to inform patients whether they had hepatitis C within one hour.

When patients tested positive, we did further blood tests where needed and, as independent prescribing pharmacists, we prescribed treatment and brought it to patients at the drop-in sessions. Medication was dispensed weekly if the patient had no safe storage. Support was given as needed; in some cases, this was through encouragement, reminders or catching up weekly at the drop-in sessions.

In other cases, support was more practical; for instance, supplying basic mobile phones so that we were able to keep in touch with patients. These phones could also be used to set daily alarms to remind them to take their medication. There were no fixed appointments, but a flexible approach was taken with patients able to have a test or a chat about treatment at a time that suited them. Some patients were given a positive result and started treatment the next week, while others would talk to us over the course of many weeks before they felt ready for treatment. Thirteen homeless or vulnerably housed patients started treatment between June 2019 and early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic closed the drop-in clinic.

The biggest reward of being part of these clinics has been hearing from those whose lives have been changed by hepatitis C treatment

COVID-19 meant that we had to adapt our approach, but we continued to work with community blood-borne virus nurses and the harm reduction team. Nurses were also able to see patients in substance misuse clinics, and pharmacists joined via Microsoft Teams calls to counsel or assess patients. Appointment times are given for these clinics, but patients receive phone calls to remind them and provide support from key workers. Missed appointments do not result in them forgoing the opportunity to be treated. This approach also proved successful, and we were able to secure health board funding to roll out pharmacist-led community clinics across North Wales.

More than 100 patients have now been treated across North Wales through pharmacist-led community clinics. Many individuals had hepatitis C for years (in one case, 20 years) but had felt unable to access treatment previously.

In 2021, the service won the Wales Advancing Healthcare Award for ‘Improving public health outcomes’. Personally, however, the biggest reward of being part of these clinics has been hearing from those whose lives have been changed by hepatitis C treatment. These have included a man who made contact with his children again after years of feeling that he was “dirty” and might pass the virus to them, and patients who felt more confident to have other health issues investigated following positive engagement with healthcare. In conclusion, this programme has enabled us to reach many vulnerable patients and make a positive and lasting improvement on their lives, their physical health and their emotional wellbeing.