Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

In the 18 years since legislation changed in the UK to allow pharmacists to become independent prescribers, the qualification has become synonymous with advanced pharmacy practice.

The term ‘independent’ not only suggests mastery of a skill but emphasises the ability to work autonomously. Before the General Pharmaceutical Council (GPhC) published updated training standards in 2021, prescribing training had predominantly attracted experienced pharmacists who saw it as a natural progression of their roles, often in specialist areas[1].

In the early days of pharmacist prescribing, it was sensible for prescribers to train in a specific therapeutic area as their ‘scope of practice’ because it gave trainee prescribers a scaffold on which to hang prescribing competencies in the context of the service they planned to support. This underscored the need for an experienced supervisor in that field.

However, from 2025/2026, all trainee pharmacists will need to demonstrate their prescribing competence ahead of registration as prescribing training becomes integrated into the initial five years of a pharmacist’s education.

This poses a distinct challenge for the pharmacy profession as many designated supervisors, responsible for overseeing trainee pharmacists during their foundation year, are not qualified prescribers themselves. NHS England requires all trainee pharmacists to also have a designated prescribing practitioner (DPP) to validate their prescribing competence.

This presents a complex workforce development conundrum for pharmacy organisations

However, DPPs are in short supply. A scoping report published by Health Education England London and the South East in 2022 revealed that there are not enough DPPs across London and the South East of England to support trainee pharmacists during their foundation year in 2025[2]. This regional scarcity tells a story all too familiar with colleagues elsewhere in the UK, indicating a significant challenge in meeting the supervisory needs of trainee pharmacists as they become prescribers.

This presents a complex workforce development conundrum for pharmacy organisations, as they look to ‘retrofit’ the traditional model of DPP supervision in a specific therapeutic area, to the newly reformed training of pharmacists.

Doing so may have serious implications for the feasibility of the foundation year and for the future of the profession.

Current training model

The traditional DPP model supports the development of a prescribing portfolio as part of a dedicated 30–60 credit, level 7 prescribing course — something that our trainee pharmacists will not have. Instead, their prescribing training will be a continuum of learning over five years, so it is important that the approach to scope of practice is integrated and the DPP model reflects this change too.

‘Superimposing’ a DPP’s scope of practice on to a trainee pharmacist could create inconsistencies in training, as each DPP’s scope of practice can vary so widely. Alternatively, choosing a specific therapeutic area for all trainees could create more challenges in pairing trainee pharmacists with DPPs, as the DPP would need to be competent in the therapeutic area chosen for the trainee pharmacist, exacerbating the shortage issue.

It is also clear that pharmacists prescribers often do not use their prescribing skills as much as they could, and find it challenging to broaden their scope[3,4]. By continuing to use the traditional DPP and scope of practice model, we risk further limiting the flexibility of the future workforce.

With this in mind, perhaps now is the time to consider alternative models that are more fit for purpose.

Rethinking scope of practice

The first step to alleviating concerns around the lack of DPPs is to rethink the concept of applying a traditional ‘scope of practice’ to trainee pharmacists as they develop their competency in prescribing.

This is reflected in the principles recently published by the NHS England Workforce, Training and Education directorate, which describes scopes of practice that “include generalist skills, aligned to processes” (e.g. medicines reconciliation)[5].

The reasons for prescribing within a ‘scope of practice’ are typically linked to patient safety. This was certainly a theme in the GPhC consultation in 2021 on revising the education and training standards[6]. However, more research is needed in this area because there is little evidence to suggest that prescribing autonomously within a defined list of medicines is always the safest option. For example, treating one disease in a patient with complex comorbidities through the prism of a ‘narrow’ scope could give rise to unconscious incompetence.

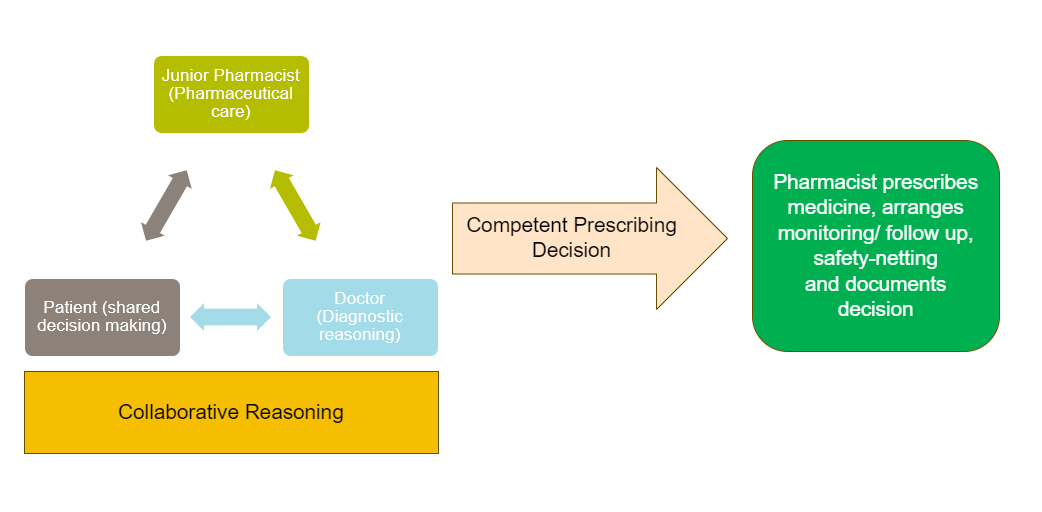

A novel approach to scope of practice could be to consider it from a service delivery perspective as opposed to a ‘therapeutic area’; for example, by using the word ‘collaborative’. Here, newly qualified prescribing pharmacists would be encouraged to support services (such as medicines reconciliation) by sharing their pharmaceutical care knowledge within a collaborative team, allowing for a competent and safe prescribing decision (see Figure). It should be noted that an important part of this collaborative approach is highlighting any prescribing restrictions, such as prohibiting the prescribing of high-risk medicines or prescribing in certain patient groups. With this approach, it is important that the pharmacist understands the diagnosis, in the same way that the doctor should understand and agree with the therapeutics.

William Swain

By reframing the approach to scope of practice as ‘collaborative’, as opposed to prescribing from a defined lists of medicines, the education and training across the first five years can focus on communication, interprofessional collaboration and the process of decision making, rather than autonomous practice in a given therapeutic area. After all, if we wanted prescribers to practice ‘independently’, we would not encourage multidisciplinary team working and shared decision making with patients quite so strongly[7].

Internationally, collaborative prescribing models involving pharmacists have showcased their effectiveness in improving patient care and medication management across various settings. Although prescribing pharmacists in Singapore are more closely aligned with the UK definition of supplementary prescribers, they are seamlessly integrated with physicians to enhance care in community contexts, underscoring the benefits of shared responsibilities in medication optimisation and chronic disease management, albeit through the statutory scaffolding of a ‘Collaborative Practice Agreement’ (CPA)[8]. This practice, mirrored in countries such as Australia, highlights the positive impact on patient outcomes and healthcare efficiency when pharmacists are empowered to prescribe and manage medications collaboratively within multidisciplinary teams, offering valuable insights for the UK[9].

For a ‘collaborative’ approach to work, trainees would likely need to access a DPP in a prescribing environment in another sector

For a ‘collaborative’ approach to prescribing training to work in community pharmacy, trainees would likely need to access a DPP in a prescribing environment in another sector, something that might dovetail with the requirement for a 13-week placement from 2026/2027. Having been trained to prescribe ‘collaboratively’, the fully qualified community pharmacist could then engage in additional service-specific training to prescribe more autonomously as required.

Concerns with collaborative prescribing

A concern with the collaborative approach to scope of practice is that early-career pharmacists might feel pressured to prescribe in situations where there is no support. This is indeed a valid concern, particularly when you consider that the annual cost pressure for NHS negligence claims was around £2.7bn in 2022/2023[10]. However, this risk can be mitigated by ensuring that graduates are equipped with a tangible understanding of legal accountability, as well as the communication tools necessary to navigate their way through such issues.

It would also be important to ensure that teams within organisations understand the differences between early-career pharmacists and more experienced ones when delivering services. This is formalised in the various named stages of training for doctors but pharmacy roles are not gatekept in the same way.

Another important question when tackling the DPP shortage is whether a single pharmacist could act as a DPP for multiple trainees? This could be realised in some settings by using a hub and spoke model. Here, other clinicians deliver the bulk of practice supervision, with the DPP responsible for monitoring overall development of competence through regular assessment and reviews of progress. It should be noted that NHS England currently requires the DPP to spend ‘sufficient time’ with trainees to be able to make an informed decision about prescribing competence.

Is the DPP role needed?

It is conceivable that by combining a collaborative approach to prescribing training, with the strategic use of the wider workforce, the need for a prescriber to act in the role as DPP could be reconsidered in some settings. By harnessing the expertise of other prescribers for practice supervision, including hands-on workplace assessments, this raises an interesting possibility: could a designated supervisor that is not a prescriber, working within such a framework, sign-off a trainee as competent to prescribe?

This concept finds some parallel in current practices within undergraduate MPharm (working to the 2021 IETS) and prescribing courses, where academic staff, not necessarily prescribers themselves, are responsible for assessing student performance in coursework and Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs). This precedent suggests that this radical approach may be viable. However, it is important to note that this endeavour would only be applicable in the short to medium term, as eventually all designated supervisors will be prescribers anyway.

As we look beyond 2026, rethinking the scope of practice and the role of the DPP in pharmacy is timely. The changing landscape, with prescribing integrated into early pharmacy training, challenges the traditional model reliant on expert clinicians as supervisors. The scarcity of DPPs necessitates a shift towards a more adaptable, collaborative approach.

Emphasising a collaborative approach over autonomous practice aligns with modern healthcare’s multifaceted nature, potentially enhancing patient safety and care quality. Revisiting supervision models, including the DPP’s role, could offer a more sustainable framework for pharmacist training and practice, addressing the complexities of contemporary healthcare delivery and the realities of multimorbidity management.

William Swain is project manager for the ‘Prescribing Integration Project’ in South East London, and lecturer (teaching) and associate director for clinical education, UCL School of Pharmacy

Disclaimer: This article is the personal opinion of the author and does not represent the policy or views of UCL or NHS England Workforce Training and Education Pharmacy directorate.

- 1General Pharmaceutical Council. Revising the education and training requirements for pharmacist independent prescribers: analysis report. 2021. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/independent-prescribing-analysis-2021.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 2Uppal Z. Independent Prescribing Scoping London & South East (LaSE) Pharmacy. Acute Trusts. 2022. https://www.lasepharmacy.hee.nhs.uk/dyn/_assets/_folder4/early-careers-tpd-programme-of-work-21-23/independent-prescribing-scoping/hee_lase_independent_prescribing_scoping_report_acute_trusts.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 3Ridge K. Pharmacist Prescribing: Professional Revolution Or Damp Squib? The King’s Fund. 2023. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/blogs/pharmacist-prescribing-revolution-damp-squib (accessed March 2024)

- 4Edwards J, Coward M, Carey N. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of non-medical independent prescribing in primary care in the UK: a qualitative systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e052227. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-052227

- 5NHS England. Prescribing Supervision and Assessment in the Foundation Trainee Pharmacist Programme from 2025/26. 2024. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Prescribing%20Supervision%20and%20Assessment%20in%20the%20Foundation%20Trainee%20Pharmacist%20Programme%20JAN%202024%20V1.2.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 6General Pharmaceutical Council. Revising the education and training requirements for pharmacist independent prescribers. 2021. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/document/gphc-revising-education-training-requirements-pharmacist-independent-prescribers-sept-2021.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 7NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf (accessed March 2024)

- 8Khee GY, Lim PS, Chan YL, et al. Collaborative Prescribing Practice in Managing Patients Post-Bariatric Surgery in a Tertiary Centre in Singapore. Pharmacy. 2024;12:31. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy12010031

- 9Percival M, McMurray A, Freeman C, et al. A collaborative pharmacist prescribing model for patients with chronic disease(s) attending Australian general practices: Patient and general practitioner perceptions. Exploratory Research in Clinical and Social Pharmacy. 2023;9:100236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2023.100236

- 10NHS Resolution. Annual report and accounts 2022/23. 2023. https://resolution.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/NHS-Resolution-Annual-report-and-accounts-2022_23-3.pdf (accessed March 2024)

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Interesting and thought provoking article. You might be interested in our NIHR study in this area:

https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR155314

INdependenT prEscribinG in community phaRmAcy; whaT works for whom, why and in what circumstancEs (INTEGRATE): Realist review study protocol. NIHR Open Res 2024, 4:72 https://doi.org/10.3310/nihropenres.13766.1

For more information please email me at i.maidment@aston.ac.uk

Thanks

Ian