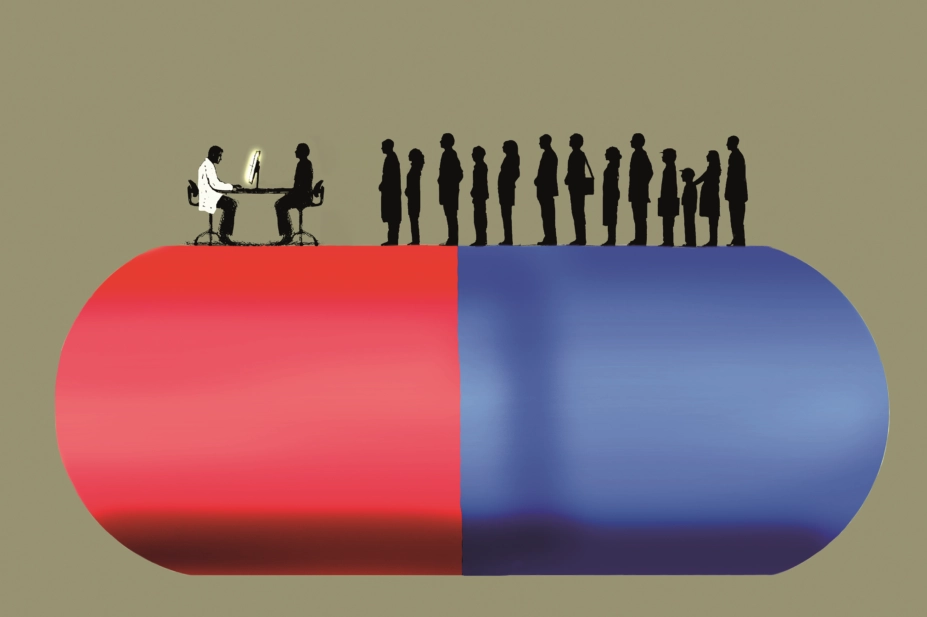

Gary Waters / Ikon Images / Science Photo Library

The new medicine service (NMS) was rolled out as an ‘advanced service’ as part of the English community pharmacy contract in October 2011, following proof-of-concept work suggesting it was effective in reducing rates of non-adherence to prescribed medication[1]

.

The NMS aims to improve adherence to newly prescribed medicines for one of four long-term conditions — type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiovascular disease (antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy). The service comprises an intervention 7–14 days after the medicine is prescribed, and a follow-up 14–21 days after the intervention. The intervention(s) consist(s) of a semi-structured interview schedule, which is designed to assess adherence, identify problems the patient may be experiencing with their medication and/or identify whether the patient needs further information or support[2]

.

When the NMS was rolled out, the Department of Health (as it was then known) allowed funding for an independent evaluation of the service, which, when published, suggested that when examined ten weeks after the presentation of the reference prescription, adherence was ten percentage points higher in the intervention (NMS) group (70.7%) than in the control (usual care) group (60.5%).

While this difference may appear fairly prosaic, we know that small increases in adherence improve health outcomes and reduce healthcare costs. For example, each 1% decrease in adherence to bisphosphonates increases the risk of hip fracture by 0.4%, and, in patients newly prescribed pioglitazone for type 2 diabetes, every 10% increase in adherence was associated with a 4% reduction in diabetes-related costs and a 2% reduction in total healthcare costs[3]

,[4]

. The NMS evaluation report also suggested that the intervention would be cost effective.

Good publicity

The report generated headlines in the pharmacy trade press: ‘Report finds new medicines service improves treatment adherence and saves NHS money’[5]

. The Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee’s (PSNC) webpages state that the evaluation’s findings were “overwhelmingly positive”[2]

. In its June 2018 report, ‘No health without mental health: How can pharmacy support people with mental health problems?’, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society stated its intention to “identify how pharmacists in community settings can be enabled to better support people with mental health problems with their medicines, such as through the inclusion of antidepressants in the new medicine service”[6]

. Concurrently, the PSNC divulged that it would lobby government to include antidepressants in the NMS as part of its discussions over the new community pharmacy contract[7]

. Thus, a credo appears to have developed within pharmacy that the NMS is uniformly effective, and not only should funding for the NMS continue, but the NMS should also be expanded to cover a greater range of newly initiated medicines.

A failure to report the results of all pre-specified outcomes leads to a distortion of the evidence base

But I do not believe such a credo is rooted in evidence. The initial trial protocol for this randomised controlled trial (RCT) stated that the primary outcomes of the trial would be “[the] proportion of adherent patients at 6, 10 and 26 weeks from the date of presenting their prescriptions at the pharmacy”[8]

. The evaluation report published only the proportion of adherent patients at 6 and 10 weeks. And in a paper subsequently published in BMJ Quality and Safety, only the proportion of adherent patients at 10 weeks was reported[9]

. In summary, here is what we know about the effectiveness of the NMS. At 6 weeks, the NMS does not appear to be effective at increasing adherence to newly prescribed medicines used to treat type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma/COPD and antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. At 10 weeks, the NMS appears to be effective at increasing adherence to newly prescribed medicines used to treat type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and asthma/COPD and for antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy. At 26 weeks, we do not know whether the NMS is effective at increasing adherence to newly prescribed medicines used to treat type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and asthma/COPD and for antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy, as these data have not yet been published.

Lack of evidence

Those data from the 26-week mark matter. If there was no difference in the proportion of adherent patients in the intervention and control groups at 26 weeks, then the difference observed at 10 weeks may start to look more like a chance anomaly than an actual result of the intervention.

More importantly, if there was no difference in adherence rates at 26 weeks, it may call into question the cost effectiveness of the intervention — an intervention that is, ultimately, funded by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). A failure to report the results of all pre-specified outcomes leads to a distortion of the evidence base, which commissioners and providers of healthcare rely on to make decisions. Therefore, those data should be published.

A recent systematic review found that, while pharmacist interventions can improve adherence to antidepressants, no positive effect on clinical symptoms was found

Add to this a less-than-impressive sample size of 500 participants, some “challenges with patient recruitment” — which led to a second phase of pharmacy recruitment for atypical ‘NMS-active’ pharmacies (one of whom contributed one-fifth of the total number of participants for the whole RCT, n=99) — and it’s no wonder the study authors stated in their evaluation that “it may not be appropriate to extrapolate findings to the entire population of England”[10]

. For a national evaluation, this is not ideal.

No data exist on the effectiveness of the NMS in improving adherence in patients newly prescribed an antidepressant. Given what we know about the effectiveness (or ineffectiveness) of the NMS in improving adherence in the four conditions for which it is currently utilised, it is premature to extend this to the treatment of a condition for which we know that adherence is particularly problematic — a 2008 study suggested that, at six months, less than 30% of patients prescribed a serotonin and/or noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor were adherent to their treatment regimen[11]

. Furthermore, a recent systematic review of pharmacist interventions to improve adherence in patients prescribed antidepressants found that, while pharmacist interventions can improve adherence to antidepressants, no positive effect on clinical symptoms was found[12]

.

This is a call for increased engagement of the pharmacy community with critical appraisal, the rational interpretation of evidence and evidence-based policy making

None of this is to say that we should abandon the NMS or that we shouldn’t expand the NMS (or a similar intervention) to include other conditions. Rather, this is a call for increased engagement of the pharmacy community with critical appraisal, the rational interpretation of evidence and evidence-based policy making. And while expanding the NMS eligibility criteria to include antidepressants may seem logical (after all, we know adherence in depression is a particular issue), this would expose the DHSC and, ultimately, taxpayers to additional costs without any evidence of return on investment. This does not mean that the eligibility criteria for the NMS are ineligible for expansion. It means that we should submit expansion to concomitant independent, rigorous evaluation.

Joseph Bush is a senior lecturer in pharmacy practice at the Aston Pharmacy School, Aston University.

References

[1] Clifford S, Barber N, Elliott R et al. Patient-centred advice is effective in improving adherence to medicines. Pharm World Sci 2006;28(3):165–170. doi: 10.1007/s11096-006-9026-6

[2] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. New Medicine Service. Available at: https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/nms/ (accessed August 2018)

[3] Rabenda V, Mertens R, Fabri V et al. Adherence to bisphosphonates therapy and hip fracture risk in osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int 2008;19(6):811–818. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0506-x

[4] Shenolikar RA, Balkrishnan R, Camacho FT et al. Comparison of medication adherence and associated health care costs after introduction of pioglitazone treatment in African Americans versus all other races in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A retrospective data analysis. Clin Ther 2006;28(8):1199–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.012

[5] Lawrence J. Report finds new medicine service improves treatment adherence and saves NHS money. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2014. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2014.20066177

[6] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. No health without mental health: How can pharmacy support people with mental health problems? Available at: https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/Documents/RPS%20mental%20health%20roundtable%20report%20June%202018_FINAL.pdf?ver=2018-06-04-100634-577 (accessed August 2018)

[7] Andalo D. Pharmacists should review every patient after a depression diagnosis, says RPS. The Pharmaceutical Journal 2018. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20204962

[8] Boyd M, Waring J, Barber N et al. Protocol for the New Medicine Service Study: a randomized controlled trial and economic evaluation with qualitative appraisal comparing the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the New Medicine Service in community pharmacies in England. Trials 2013;14(1):411. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-411

[9] Elliott RA, Boyd MJ, Salema N-E et al. Supporting adherence for people starting a new medication for a long-term condition through community pharmacies: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of the New Medicine Service. BMJ Qual Amp Saf 2016;25(10):747–758. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004400

[10] Elliott R, Boyd M, Waring J et al. Department of Health Policy Research Programme Project. Understanding and Appraising the New Medicines Service in the NHS in England (029/0124): A randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation with qualitative appraisal comparing the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the New Medicines Service in community pharmacies in England. 2014. University of Nottingham, UCL School of Pharmacy

[11] Sheehan DV, Keene MS, Eaddy M et al. Differences in medication adherence and healthcare resource utilization patterns. CNS Drugs 2008;22(11):963–973. PMID: 18840035

[12] Readdean KC, Heuer AJ & Scott Parrott J. Effect of pharmacist intervention on improving antidepressant medication adherence and depression symptomology: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2018;14(4):321–231. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.05.008

You may also be interested in

Pharmacy2U could provide up to 3,000 telephone NMS appointments each month

Patients twice as likely to continue taking medicines if warned about health impact of non-adherence