CTK / Alamy Stock Photo

Without Oscar Eckenstein, mountaineering as we know it today would not exist. Responsible for the invention of crampons — de rigueur for the modern mountaineer — the English railway engineer, born in 1859, is recognised as the first true innovator of climbing equipment for the masses.

Crucial to his success was that his inventions were not only revolutionary but affordable, and the same applies whether we are talking about mountaineering gear or life-changing medicines.

During my own high-altitude hijinks, I carried not only crampons but a first aid kit containing dexamethasone. This generic (off-patent) drug is used to treat climbers with cerebral oedema — an altitude-induced condition that, untreated, can be fatal.

In 2020, this drug was also found to be the first effective treatment for patients with COVID-19 and it has since helped save the lives of approximately 22,000 people in the UK and an estimated 1 million worldwide.

Crucially, we did not have to scale to new pricing heights to supply this treatment, because it was off-patent.

From dexamethasone to the medicines for intensive care units, generics have underpinned the fight against COVID-19. Over the past 18 months, the generics industry has delivered repeatedly, including supplying the bulk of the UK’s manufacturing capacity for the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

Biosimilar and generic manufacturers’ inventiveness includes developing new therapies, novel manufacturing processes and pioneering business models, all of which are core to our national health and the UK economy.

Crucial timing

Medic repurposing is exciting because it brings new, yet affordable, treatments for previously unmet patient needs, and this affordability is crucial for an NHS with finite resources.

For example, the British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA) is working collaboratively with the NHS, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, clinical research groups and medical research charities to repurpose the generic breast cancer medicine anastrozole, to be used to prevent breast cancer in post-menopausal women at increased risk. Breast cancer is the most common cancer in UK and the leading cause of death in women aged 30–55 years. Therefore, many thousands of women would benefit from this innovative breakthrough.

Using a low-cost generic medicine to address an unmet patient need is also highly cost-effective for the NHS, compared with the expense of a patent-protected product. Also, the development of drug-delivery devices are beginning to make treatments far more effective.

For example, in 2013, pharmaceutical company Ethypharm created the world’s first ‘take home’ opioid overdose kit and supplied it to Scotland’s Drugs Death Taskforce. According to the taskforce, this innovation helped save around 1,400 lives in Scotland in 2020.

A unique market

Seven out of the ten largest medicine suppliers to the NHS are generic manufacturers and they are crucial — as demonstrated throughout the COVID-19 pandemic — for supply resilience.

In many aspects, the UK market is unique compared with other parts of Europe. Freedom of pricing delivers the lowest generic drug prices in Europe, yet also provides a multi-source market that limits the impact of shortages. If one supplier has supply problems, others can fill a void. In contrast, the EU’s alternative procurement methods — such as tendering in primary care — lead to far more frequent drug shortages.

Without a supportive policy environment from the UK government, the NHS could soon be left dangling on a thread

For example, at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, members of the BGMA reported that demand for specific lifesaving anti-retrovirals and ventilation drugs had skyrocketed by more than 1,000%. Companies maintained supply by revising their manufacturing schedules and supply chains to meet the NHS’s rapidly changing needs.

However, these have been testing times for this industry. As well as being at the forefront of the pandemic, the BGMA was involved in extensive preparations for Brexit and the significant issues with the Northern Ireland Protocol’s implementation.

As an example, generic manufacturers were asked on several occasions to hold stockpiles of critical medicines in readiness for any issues caused as a result of leaving the EU. Since then, the industry has also been heavily involved in discussions on the impact of the proposed implementation of the Northern Ireland Protocol. The BGMA has warned that owing to significantly increased complexity and duplication — and, as a result, cost — caused as a result of the Protocol, manufacturers may be forced to withdraw products from Northern Ireland. This could also impact the launch of future new products.

In the current UK market, there are severe threats to regular business for generics manufacturers. These include an unsustainable pricing system, the voluntary scheme for branded medicines, or VPAS. VPAS applies not only to originator products but also to generic and biosimilar products that carry a brand name, even if they operate in multi-source markets. Branded generic and biosimilar manufacturers must pay a rebate (15% in 2022, projected to be 23.7% in 2023), even if competition is working to significantly lower what the NHS already pays.

Generic manufacturing companies have also reported significant problems in the UK’s life sciences ecosystem, such as systemic delays in medicines regulation and a shortage of qualified personnel. Without a supportive policy environment from the UK government, the NHS could soon be left dangling on a thread.

The biosimilar and generics industry has a fundamental role in our national health, so why has it largely been ignored in the government’s life science policies? The Department of Health and Social Care has an innovation minister — Lord Kamall, minister for technology, innovation and life sciences — but there is no single minister responsible for all aspects of the country’s medicines supply; this must change.

The UK’s health system currently disincentivises innovation by biosimilar and generic companies. For example, if you invest in research and development (R&D) into a new molecule, you can patent it and sell the resultant medicine at a high price for a return on the investment. However, invest R&D in repurposing an existing drug — like with dexamethasone — and your competitors will benefit from your investment as there is no patent protection.

Without R&D costs to recoup, competitors can sell the same product cheaper and gain market share, meaning there is no incentive to repurpose old molecules. While NHS England is looking at this and making some welcome progress around tendering costs, the UK’s life sciences ecosystem offers uncertain support for drug repurposing.

There must be equal room for generic medicines manufacturers and the originator sector in the expedition tent

It is a similar scenario when it comes to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). It is not easy to put a drug through a NICE appraisal but it is not a problem for companies whose drugs have patent-protected exclusivity. However, without a patent, it is a disadvantage to be the biosimilar company that pays for a NICE appraisal: other companies can later make profit without paying out for the original appraisal.

The UK government has a new ministerial team in Lord Kamall and science minister George Freeman, but they need a new approach when it comes to generic medicines.

There must be equal room for generic medicines manufacturers and the originator sector in the expedition tent. For example, the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy and Office for Life Sciences’ ‘Life Sciences Vision‘, published in July 2021, had innovation at its heart, yet provided nothing specific to generic or biosimilar companies.

Both sides of the pharmaceutical industry matter and, as Oscar Eckenstein taught us with his game-changing climbing equipment, innovation does not have to be costly to be effective, but it does have to be accessible.

The author has not declared any conflicts of interest in relation to this article

You may also be interested in

Labour Party’s compulsory licensing plans would ‘undermine’ medicines development, says pharmaceutical industry

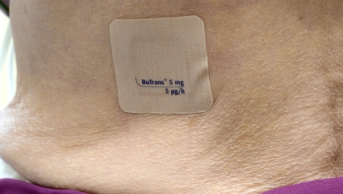

Delayed market entry for generic buprenorphine patches could have cost NHS £500,000, study concludes