There are few elements of the COVID-19 pandemic that anyone wants to revisit; however, progress made in narrowing the ethnicity awarding gap in MPharm programmes should now be one of them.

An analysis of data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) by The Pharmaceutical Journal has revealed this month that in 2021/2022 and 2022/2023, only 83% of ethnic minority graduates received a first or 2:1 in their MPharm degrees, compared with 94% of white graduates.

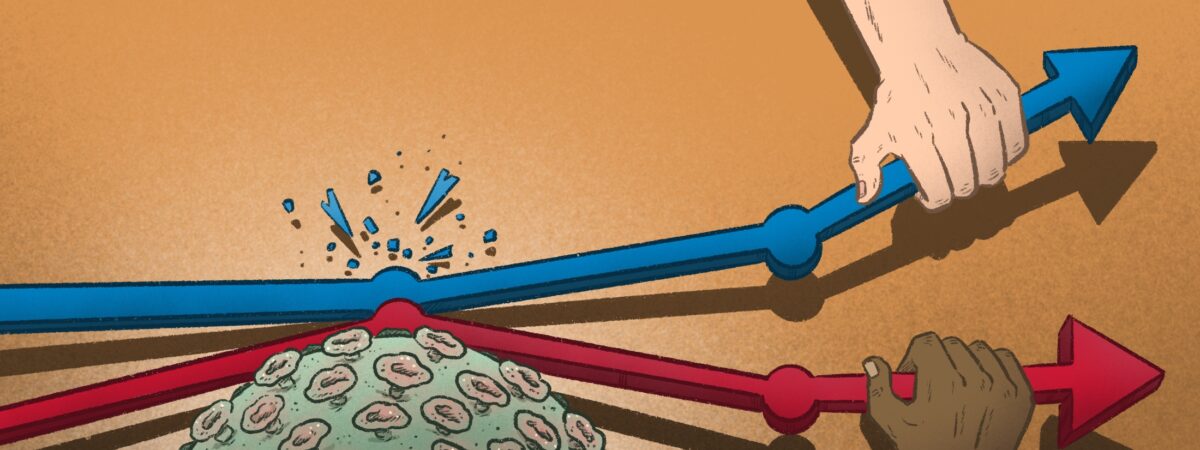

This 11-percentage point disparity represents a rewidening of the ethnicity awarding gap after two years of progress in narrowing the gap during the pandemic. Previous analyses of the same data had shown the gap to have reduced from 12 percentage points in 2017/2018 and 2018/2019 to 8 points in 2019/2020 and 2020/2021.

The picture is worse for Black pharmacists. The Pharmaceutical Journal’s latest analysis shows an awarding gap of 17 percentage points — up from 12 points during the pandemic years and 15 points before the pandemic.

The recent widening underscores the need for more concerted and persistent efforts

Ethnicity awarding gaps in the MPharm programme remain a deeply concerning disparity that has long raised fundamental questions of equity and social justice within pharmacy education. This regression is not merely a statistical fluctuation; it represents a setback in the pursuit of equitable outcomes for all pharmacy students and necessitates immediate attention.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) has rightly called the widening gap “deeply concerning”, highlighting the lasting impacts on individuals and the profession, and has set up a working group to assess the awarding gap for Black pharmacists, specifically. In a report published in February 2024, the RPS made several recommendations to address the gap, including removing bias from assessments, improving the transition from secondary education, supporting overseas students, and strengthening data collection, that provide a valuable framework for action.

However, the recent widening underscores the need for more concerted and persistent efforts. Pharmacy schools, in particular, must now critically examine which aspects of the pandemic-era adaptations proved beneficial and explore how these can be strategically incorporated into their long-term approaches to teaching. For example, the temporary narrowing of the gap during the pandemic suggests that the changes in assessment methods — with a greater reliance on coursework and continuous exams — may have inadvertently levelled the playing field to some extent.

This requires a comprehensive review of assessment strategies, a commitment to decolonising and diversifying the curriculum, and ongoing investment in staff training on unconscious bias and inclusive teaching practices. Furthermore, robust data monitoring and transparent sharing of awarding gap data are essential for tracking progress and fostering accountability.

Reasons behind the awarding gap are known to be multifaceted and therefore require a multifaceted response that also looks at the student beyond their academic life. This means enhancing student support mechanisms, such as academic coaching and mentoring programmes, are also crucial to ensure all students have the opportunity to succeed.

Failing to close the awarding gap not only disadvantages these students but also limits the diversity of the pharmacy workforce

It is vital in this endeavour to consider the perspectives of students themselves. Research published in the Journal of Further and Higher Education in December 2024 suggested that looking at awarding gaps at a module level (rather than a final degree award), combined with a commitment to listening to students’ experiences, is essential to developing effective strategies to reduce awarding gaps. Engaging with students from diverse ethnic backgrounds to understand their challenges and co-create solutions can foster a more inclusive and equitable learning environment.

The fact that nearly three-quarters of pharmacy students graduating in 2021/2022 and 2022/2023 were from an ethnic minority background underscores the urgency of addressing this inequity. Failing to close the awarding gap not only disadvantages these students but also limits the diversity of the pharmacy workforce, potentially impacting the profession’s ability to effectively serve increasingly diverse patient populations.

The temporary narrowing of the awarding gap during the pandemic offers a beacon of hope and a valuable learning opportunity. Pharmacy schools must seize this opportunity to critically analyse what worked, why it worked, and how those lessons can be applied to create a sustainable and equitable educational environment for all MPharm students.

The time for reflection and renewed action is now, to reclaim the progress made and ensure a truly inclusive future for the pharmacy profession. PJ