Fred Goldstein/Dreamstime.com

This content was published in 2010. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Ensuring the accuracy and continuity of patients’ medication when they are admitted to hospitals is now common practice. However, there has been less regard for such medicines reconciliation once care is transferred back into the community. Consequently, there is a risk that medication changes made in hospital are not communicated effectively to GPs and other community healthcare professionals.1,2

Research suggests that around 60% of all medication errors in hospital occur as a result of poor communication when patient care is transferred (ie, between wards or during admission or discharge).3,4 Other studies suggest that 40–50% of patients have at least one discrepancy in their discharge information, with the most common reasons for error being that medicines are incompletely prescribed (eg, have incomplete or inaccurate instructions)5 or are omitted.6,7

In 2007, a systematic review found that, in general, deficits in communication and information transfer at hospital discharge are common and may affect patientcare.8 This is likely to include communication about medicines and intentions for prescribing and monitoring.

Last year, at a workshop held jointly by the Primary Care Pharmacists’ Association and the United Kingdom Clinical Pharmacy Association, pharmacists’ roles in the transfer of care between healthcare sectors were explored.

During the meeting, four work groups were asked to consider changes to current ways of working or new services that could improve the accuracy and communication of patients’ medicine regimens when they are discharged from hospital. During the meeting, the following ideas and statements of best practice were generated.

Planning for discharge

After medicines reconciliation has occurred, the reason for any subsequent medication changes should be documented — either on the patient’s drug chart or in his or her medical notes. This would include indications for new medicines, reasons for altering doses and reasons for treatment being discontinued. This would allow a summary of medication changes and the rationale behind them to be retrieved easily and quickly when a discharge advice letter is written for the patient’s GP.

Whether the changes should be recorded in the notes or on the drug chart was a subject of considerable debate. Recording on the drug chart makes the information more accessible. It also helps to educate junior doctors and others on the reasons for medication changes (eg, a drug or disease interaction). The advantage of recording in the medical notes is that it creates a permanent record that might be useful during subsequent admissions. However, the medical notes are less transportable so they cannot be moved as easily to another part of the hospital (eg, pharmacy) for the discharge letter to be written.

It was agreed that writing on the drug chart was the most useful method but important and complex medicines management information should also be written in the medical notes.

THERE IS EVIDENCE THAT AROUND ONE THIRD OF ADVERSE DRUG EVENTS OCCURS AS A RESULT OF PATIENTS INADVERTENTLY TAKING THE WRONG MEDICINES AFTER DISCHARGE

These ideas are encompassed in the term “planning for discharge”.9 As soon as patients are admitted to hospital, pharmacists should start planning for their discharge so that the correct information is captured and can be quickly retrieved when the discharge advice letter is written. This concept has been put into practice formally at Barts and The London NHS Trust (see Box, p176).

Care plans

A care plan for the GP should be written by the pharmacist for patients considered to be at high risk of medicines misadventure. This will tend to be those individuals prescribed the highest number of medicines (eg, patients admitted to care of the elderly or cardiac wards).9

Since writing care plans is a time-consuming process, using risk factors to identify high-risk patients will be necessary. Possible risk factors might include:5

- Medicine factors —medicines with high risk for side effects and toxicity, those needing titration or monitoring after discharge

- Patient factors — eg, people with poor renal function, polypharmacy, etc

- Social factors — individuals who are socially isolated, have cognitive impairment, or have been prescribed a compliance aid

Where social factors are identified as a risk factor, healthcare staff need to determine ways to help the patient (eg, large print labels, compliance aids, use of medicines with once-daily dosing). Any proposed solutions should then be forwarded, along with other discharge advice, to community pharmacists, GPs, district nurses and community matrons to ensure that the necessary interventions can been acted in primary care.

Patient counselling

There is evidence that around one third of adverse drug events occurs as a result of patients inadvertently taking the wrong medicines afterdischarge.10 Patients are not always told about medication changes when they are in hospital so may be unaware of which ones to take when they get home.11

Ideally, clinical pharmacists should talk to all patients before discharge to make sure any medication changes, and the reasons for them, have been made clear. This, however, is not always possible because of the time commitment required to do so and because patients are often discharged outside pharmacists’ working hours.

An alternative would be to offer training to nurses on how to provide this type of counselling. In addition, further training on consultation skills might help nurses to explore patients’ concerns about taking medicines.

Electronic discharge notes

Although some trusts have electronic discharge forms, these are not truly “electronic” (ie, the information is usually not transferred electronically to patients’ GP records). In addition, there may be issues about how well such notes are completed. For example, treatment durations might not be documented, new medicines might not be clearly identified as such and, if patients’ medicines are not reconciled properly, the notes could include an incorrect list of medicines. On the plus side, electronically produced notes are always legible.

If pharmacists were to complete these discharge medicine forms then, in the same way that pharmacists improve the accuracy of medicines reconciliation on admission, the accuracy of such forms could be improved.12

GP practice procedures

Many attendees believed that not all GP practices have systems in place to ensure care plans are implemented safely and consistently once discharge advice letters are received from hospitals. Guidelines could be developed on how to manage discharge information.

In particular:

- How to reconcile medicines and update patients’ medicine lists

- How to ensure that follow-up monitoring (eg, blood tests, consultations to check for treatment efficacy or adverse events) and necessary medication alterations occur

- How to identify patients at risk of medicines misadventure due to adherence issues

Medicines hotline

Medicines reconciliation often involves hospital staff contacting GP practices for information on patients’ regular, long-term medicines. However, getting through to busy practices is often a problem. To solve this, each surgery could provide a “medicines hotline” for hospital staff to call when requesting such information.

Managing repeat lists

Often, GPs maintain lists of patients’ long-term medicines in their electronic records in the form of “repeats”. Many will include in this list medicines prescribed by other clinicians to ensure that drug-drug and drug-disease interactions are identified. However, GPs need to be aware that if a surgery does not issue a medicine, pharmacy or other hospital staff might interpret the “last issued” date to mean the patient is no longer taking the medicine. To resolve this, GPs could include information within the repeat record for such medicines that identifies who is the main prescriber (eg, “being prescribed by hospital renal team”).

Post-discharge MURs

Some patients experience adverse drug events because they are confused about which medicines to take.11 Community pharmacists could help patients understand which medicines to take and how to take them — along with any “dos and don’ts” — using post-discharge medicines use reviews (MURs); a system where these can be requested by GPs, hospital staff and patients themselves should be available. Ideally, such MURs would occur after the GP has reviewed the patient’s medicines and performed a clinical medication review to ensure his or her records have been updated appropriately.

Domiciliary MURs

Many patients discharged from hospital are housebound and therefore unable to visit a pharmacy to receive an MUR. However, there is scope for primary care trusts to fund domiciliary MURs as a locally enhanced service.

Such reviews do not necessarily need to be conducted by community pharmacists. If a PCT were to commission this service, the tendering process could be opened more widely and reviews could be conducted by pharmacists employed by the PCT’s provider arm, a private company or an acute hospital trust. Furthermore, less complex cases could be handled by pharmacy technicians.

Training new staff

At undergraduate level and during training years, doctors and pharmacists should receive more training about the medicines-related risks that arise during the transfer of patient care (EDITOR— see INNOVATION & COLLABORATION, p187). This should provide an appreciation of the problems faced by patients and other healthcare professionals when the reasons for medication changes are not documented and communicated effectively. By encouraging a cultural change, an improved way of working can become normal practice rather than being seen as an additional duty that doctors and pharmacists are expected to take on.

Justification and funding

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence/National Patient Safety Agency medicines reconciliation guidance has provided a mandate to hospitals to put additional resources towards medicines reconciliation on admission. We urge the NPSA to impose a similar mandate for carrying out medicines reconciliation on discharge since this is a likely source of medication errors.

If resources are needed to fund new posts then there may be ways of justifying the service to PCT commissioners and hospital managers. For instance, business cases should provide evidence for the impact of new services (eg, fewer adverse effects caused by medicines) and the financial impact of a new service (eg, fewer readmissions, reduced litigation caused by medicines misadventure). In addition, it may be possible for the PCT to include planning for discharge within its local “Commissioning for quality and innovation” (CQUIN) scheme. This scheme rewards hospitals financially for improving their quality of care. Improving the discharge process clearly improves quality; gaining the views and support of patients might be necessary when preparing the necessary business case.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The authors thank those PCPA and UKCPA members who attended the meeting, which was held on 24 September2009 at the Liberal Club, London.

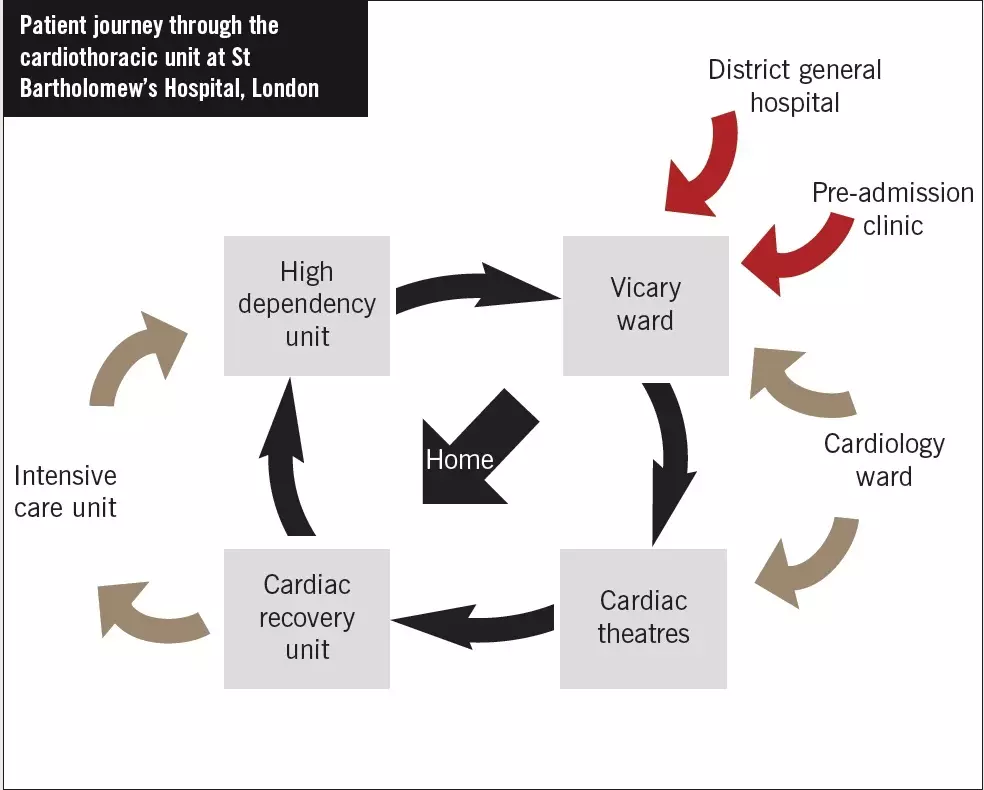

A new way of working at St Bartholomew’s Hospital

Planning for discharge need not necessarily require new funding. It can be implemented using new ways of working and through education and training. In 2008, the clinical pharmacy service provided to the cardiac ward at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London, was reviewed and remodelled. Here, the flow of patients through the hospital’s cardiothoracic unit is described (see Figure below).

Throughout their hospital admission, cardiac surgery patients often have some of their medicines (eg, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) withheld temporarily after their operation due to possible haemodynamic instability (eg, low blood pressure, acutely impaired renal function). As part of the remodelled way of working, all ward pharmacists are required to ensure they gain a basic understanding for why each patient is admitted (ie, for which procedure). In addition, a list of the medicines taken by the patient before admission must be documented; this list should be annotated if any of those medicines is used for an unusual or non-cardiac indication (eg, tamsulosin for benign prostatic hyperplasia). Pharmacists must also make sure the following information is documented in the patient’s drug chart:

- If a medicine has been stopped (including why)

- If a new medicine has been prescribed (including its indication)

- The intended duration of treatment if a medicine is prescribed short term (eg, antibiotics)

- If the dose or frequency of a medicine has been changed (including why)

If a new drug chart is required, all relevant information from the old chart is transcribed onto the new one. Pharmacists must then check and sign the new chart to confirm that all information has been transferred correctly. This way of working allows relevant information to be written into the discharge advice letter without the junior doctor having to refer to the patient’s medical notes. This is particularly important if an unplanned discharge is required and the discharge prescription cannot be screened by a pharmacist on the ward. It also minimises the risk of medication errors occurring when a patient’s care is transferred (eg, between wards or between hospitals).

Education has been provided for medical staff to ensure they are aware of where the information relating to medication changes should be written.

Although it may seem daunting to change practice in this way, pharmacists have found the additional time required to complete their tasks is minimal. The department is now continuing this work in close liaison with local primary care trusts to identify what information GPs would like to receive when patients are discharged to minimise the risk of medication errors.

References

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Annals of Internal Medicine 2003;138:161–7.

- Wong JD, Bajcar JM, Wong GG, et al. Medication reconciliation at hospital discharge: evaluating discrepancies. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2008;42:1373–9.

- Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Archives of Internal Medicine 2005;165:424–9.

- Rozich JD, Resar RK. Medication safety: one organization’s approach to the challenge. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management 2001;8:27–34.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, et al. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Archives of Internal Medicine 2005;165:1842–7.

- Vira T, Colquhoun M, Etchells E. Reconcilable differences: correcting medication errors at hospital admission and discharge. Quality & Safety in Health Care 2006;15:122–6.

- Nickerson A, MacKinnon NJ, Roberts N, et al. Drug-therapy problems, inconsistencies and omissions identified during a medication reconciliation and seamless care service. Healthcare Quarterly 2005;8(special):65–72.

- Kripalani S, Yao X, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance medication adherence in chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine 2007:167;540–50.

- Hudson SA, Boyter AC. Pharmaceutical care of the elderly — drug use in elderly patients. Pharmaceutical Journal 1997;259:686–8.

- Campbell F, Karnon J, Czoski-Murray C, et al. Systematic review for clinical and cost effectiveness of interventions in medicines reconciliation at the point of admission. December 2007. www.nice.org.uk (accessed15 April 2010).

- Richards N, Coulter A. Is the NHS becoming more patient centred? September 2007.www.pickereurope.org (accessed 15 April2010).

- Department of Health. Using the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation(CQUIN) payment framework. Updated December 2009. www.dh.gov.uk (accessed15 April 2010).