istockphoto.com

In October 2014, Europe’s medicines regulator, the European Medicines Agency (EMA), scrapped proposed restrictions on the sharing of clinical trial data that it considers for medicine approval. Those restrictions would have made the independent scrutiny of data almost impossible. Supporters of AllTrials — a campaign launched in January 2013 which calls for all past and present clinical trials to be registered and their results reported — welcomed the move as a big step forward for clinical trial transparency in Europe. Unfortunately, the EMA has not gone far enough: pharmaceutical companies will still be permitted to redact their clinical trial data selectively, putting the transparency of the new policy at risk. The EMA needs to heed the many calls to fix this much anticipated policy on the sharing of clinical trial data in order to promote transparency of the medicines approval process.

Chequered history

In December 2010, the EMA implemented a policy allowing it to disclose on demand clinical study reports (CSRs) — detailed clinical trial documents that often contain thousands of pages of information — for each drug it reviewed. Between June 2013 and September 2013, hundreds of patients, doctors, researchers and organisations such as the UK’s medicines appraisal body the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and the European Consumer Organisation wrote to the EMA in support of its proposals to publish CSRs.

At the same time as the EMA was discussing its policy, the European Parliament was considering a new law on regulating clinical trials. Between February 2014 and April 2014, hundreds of citizens — and organisations representing millions of people, including the European Patients Forum, which represents 150 million patients, and the European Association of Hospital Pharmacists, which represents tens of thousands of pharmacists across Europe — wrote to Members of the European Parliament and health ministers from all EU countries urging them to support transparency amendments to the proposed EU Clinical Trials Regulation. The European Parliament agreed and passed the new regulation on 2 April 2014. This means that it will soon be law that all clinical trials on drugs in Europe must be registered before they begin and make public a summary of their results within a year of the trial’s end. The new regulation supports the EMA’s transparent publication of clinical study reports by making it law that information in clinical study reports should not generally be considered commercially confidential.

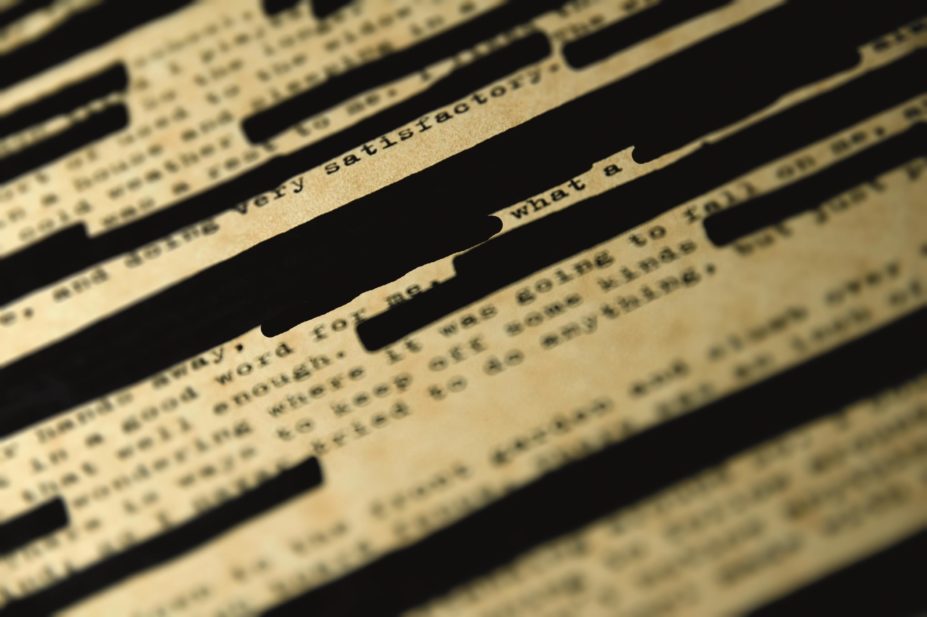

Then in May 2014, the EMA looked set to make a U-turn. Two US-based pharmaceutical companies, AbbVie and InterMune, filed lawsuits against the EMA in the European Union General Court in early 2013 to prevent the EMA from releasing CSRs from trials on their drugs, the anti-inflammatories Humira and Esbriet. On 3 April 2014, AbbVie announced it had reached an agreement with the EMA and was dropping its case. By the end of May 2014, InterMune followed suit and dropped its case against the EMA. As part of the agreements, the EMA agreed to redact some of the information from the companies’ CSRs, prompting the European Ombudsman to ask the regulator why large amounts of information were kept hidden. On 16 May 2014, the EMA held a stakeholders meeting about its policy, which we expected to be in line with its previous commitment to transparency and its renewed mandate from the European Parliament.

Instead, the EMA proposals said that CSRs would only be available for on-screen viewing preventing researchers from comparing different trial information because CSRs can be hundreds or thousands of pages long. Such a ridiculous restriction would mean that researchers would effectively be prevented from comparing data sets. Moreover, pharmaceutical companies would be able to redact CSRs selectively.

AllTrials and hundreds of people called on the management board of the EMA to go back to its earlier proposals. The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, a member of AllTrials, launched a social media campaign pointing out the absurdities of the restrictions. Following this pressure, the EMA agreed to drop the on-screen only restriction and published the policy online. The new policy, agreed in October 2014, allows researchers to download, save and print CSRs.

Outstanding concerns

Although progress has been made, the EMA’s policy is still flawed. The first CSRs will not be released until at least June 2016, meaning that decades of trial data about the medicines being used by patients today will remain unavailable to researchers. The policy’s redaction principles put primary responsibility for redactions into the hands of trial sponsors. This means that people running clinical trials get first say on which information should be withheld from the public. The EMA will then consider the reasons given for any redactions and any disagreement between the trial sponsor and the EMA will need to be settled in court. Sections of CSRs could be stuck in legal limbo for months or even years while the limits of commercial confidentiality are defined.

It is unknown how much information will be kept from the public eye. The EMA’s agreement earlier this year allowed AbbVie to censor information on protocol changes from the public release of a CSR. Protocol changes in a trial are precisely the kind of information that researchers need to scrutinise to determine whether that trial was a fair test of the treatment. It is difficult to understand why it is justifiable to withhold protocol changes from a trial conducted eight years ago, on overriding grounds of commercial confidentiality.

A clear sky

The EMA’s promises to be proactively transparent are part of a global trend toward greater openness of clinical trial information. Momentum from governments, funders and regulators worldwide has persuaded the World Health Organization (WHO) that it needs a statement on reporting results for clinical trials for the first time. In November 2014, dozens of organisations, including the European Cancer Patients Coalition, the Canadian Cancer Society and the Cochrane Collaboration, and many more people wrote to WHO in support of its draft statement on trial reporting and called on WHO to go further by including the results from past trials in its policy.

The US Government has proposed expanding reporting of clinical trial results and to make registration and results reporting a condition of federal research funding. Already hundreds of AllTrials supporters have written in support of the proposals.

These initiatives mean that in the future more clinical trial information will be available for public scrutiny. But we need to keep the pressure on industry and academia to report the results of trials done in the past. These are the trials that inform the use of today’s medicines.

The EMA has said that it will begin consulting on providing researchers with access to anonymous individual patient data from trials. But the redaction principles by the EMA are out of step with initiatives from some parts of the pharmaceutical industry to share data from clinical trials. For example, the sample data-sharing agreement for ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com, the multi-source data sharing portal set up by GlaxoSmithKline, does not contain any sections on redactions, establishing “none” as a reasonable number of redactions and leaning towards the minimum possible. The information that can be redacted from Johnson & Johnson’s trial data accessible through the Yale Open Data Access Project is limited to “information that could permit re-identification of participants, investigators, or study locations”.

As the regulator charged with evaluating medicines for more than half a billion people, the EMA should be leading the way in transparency and not allowing redactions that could limit the analyses of data or delays to prevent the release of the valuable information it holds. The new EU Clinical Trials Regulation says that “in general the data included in a CSR should not be considered commercially confidential”, so the EMA should adopt this standard, too. The EMA’s decisions on any redactions should also be independently audited so that trial sponsors are not allowed to hinder access to important information on benefits and harms contained within clinical trials.

There are too many loopholes in the current policy to allow full transparency and, without this, research could be hampered and patients may not fully benefit from treatments and may even come to harm.