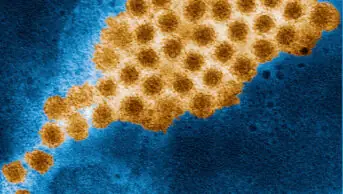

Shutterstock.com

Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/wuhan-novel-coronavirus

Source: Shutterstock.com

In the midst of the worst pandemic in a century, with more than 150,000 people already dead from COVID-19, it is understandable to yearn for a cure. Researchers around the world have dropped everything to develop effective treatments and vaccinations for this deadly disease, with several frontrunners emerging over the past few weeks.

Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine — commonly used to treat malaria, rheumatoid arthritis and lupus — have sparked particular interest within the international media and, indeed, among world leaders. At a press briefing on 19 March 2020, US president Donald Trump labelled hydroxychloroquine as one of the drugs that “could be a game changer” when it comes to treating COVID-19, going on to say a couple of weeks later that trying to treat patients with the drug “can help them, but it’s not going to hurt them. What do you have to lose?”

Prescribing chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine outside of clinical trials for patients with COVID-19 can hurt them

The problem is that prescribing chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine outside of clinical trials for patients with COVID-19 can ‘hurt them’ and others too. For a start, their efficacy against the disease is unproven, with evidence so far coming from preclinical studies, anecdotal evidence and a few small trials.

Moreover, they have known side effects. The American Heart Association, American College of Cardiology, and Heart Rhythm Society have issued recommendations on using hydroxychloroquine and the antibiotic azithromycin— a combination touted for potential prophylaxis or treatment of COVID-19 — highlighting it should be withheld in patients with a prolonged QT interval, owing to potentially fatal arrhythmias.

However, prescribing these medicines does not only affect individual patients being treated for COVID-19, where, you could argue, the benefits might outweigh the risks. It has wider implications.

If chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine are prescribed outside of clinical trials, it is “a wasted opportunity to create information that will benefit others”, as the UK’s chief medical officers put it, in a recent letter to NHS colleagues.

It could also harm those who already rely on these medicines for their approved uses. The global supply of medicines is fragile and a sudden surge in demand for COVID-19 patients could mean those with rheumatoid conditions or malaria go without. What is needed is robust, high-quality data, which can only be obtained from large, randomised controlled trials.

Right now, dozens of drug candidates are being trialled for both prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19, ranging from antivirals to convalescent plasma. In the UK, there are three national trials — PRINCIPLE, RECOVERY and REMAP-CAP — which are gathering evidence across the whole spectrum of disease, from primary care to intensive care.

The researchers leading these trails aim to recruit thousands of patients and are running the trials as simply as possible to reduce the burden on NHS workers, who are already working flat out. The trials also have adaptive designs, so that more treatments can be added if new, promising candidates are identified.

The faster patients are recruited, the quicker we will have answers and, at the rate the disease is spreading, we shouldn’t have to wait too long.

You may also be interested in

Norovirus and strategies for infection control

Case-based learning: insect bites and stings