Introduction

The NHS plan for England states that, by 2004, patients should be seen either by a GP within 48 hours or by another primary care professional within 24 hours.[1]

Improved access to health care and redesigning services around patients is a key target for primary care trusts.[2]

GP practices are thus under enormous pressure to meet rising patient demands and expectations and to achieve Government objectives.

Research has shown that one in three GP consultations are for minor illnesses and between 20 and 40 per cent of GP time is spent on minor ailments.[3]

At least 10 per cent of common ailments are still presented to the GP, equating to 96 million consultations a year or 300,000 consultations each day.3 If these minor ailments could be successfully treated by allied health professionals, GPs would have more time to spend on those patients with more serious conditions.

One of the initiatives that have been developed to facilitate this are community pharmacy-based minor ailment schemes (MASs). These schemes allow the community pharmacist to supply medicines free of charge from a limited formulary for a range of minor ailments for patients who would otherwise visit their GP to obtain a free prescription. The Government has made a commitment to promote the establishment of MASs, and to increase the choice of where, when and how medicines may be obtained, in the document “Building on the best”.[4]

In addition the Government has stated that “community pharmacies are well placed to be a first point of call for minor ailments” in the White Paper “Our health, our care, our say”.[5]

MASs also fulfil the goals of “A vision for pharmacy” in that they provide convenient access to medicines and allow pharmacists to be a point of first contact for health care services for people in the community.[6]

Chorley & South Ribble PCT has developed an MAS called “Care in the pharmacy”. The scheme covers 17 minor ailments which, together with a formulary, were agreed with the local medical committee, the local pharmaceutical committee and the PCT’s prescribing subcommittee. On the whole, GPs and pharmacists were enthusiastic about the introduction of the scheme although some GPs did express reservations about the suitability of pharmacists prescribing for minor ailments in a busy shop environment and the perceived diminution of the doctor’s role in treating certain illnesses.

Previous schemes have been restrictive in that access has been limited to those patients who have first contacted their practice or have been issued with a voucher.[7]

Other schemes have tied patients to a particular pharmacy by requiring registration.[7]

“Care in the pharmacy” allows either surgery referral or self-referral and does not require registration, thus allowing greater flexibility and ease of access, while ensuring that practice workload is not increased.

The scheme is open to all, but patients who are not exempt from prescription charges are required to pay the current fee. However, all medicines within the formulary are currently below the prescription charge levy.

Patients are given a “passport” at the pharmacy when they first access the scheme. The patient’s name, address, date of birth and details of the minor ailment treated are recorded by the pharmacist in this passport. Patients must present this passport at any participating pharmacy for all subsequent treatments. The passport allows pharmacists and GPs to view easily the details of previous MAS consultations. A form must be completed for each consultation.

“Care in the pharmacy” was introduced as a supplementary enhanced service accessible via community pharmacies in October 2004.

Aims

For the purposes of this paper I aimed to determine patients’ views on the MAS so that feedback gained could be used to inform future service development.

Method

A patient questionnaire was devised based on the Tyne and Wear Health Action Zone example given in the National Pharmacy Association toolkit “Implementing a community pharmacy minor ailment scheme”.[8]

This was adapted to reflect issues of patient choice, access and convenience and treatment around our MAS.

Whereas the original questionnaire used a numbering format where “1” indicated strong agreement and “4” strong disagreement, the adapted questionnaire used an “agree/disagree/not so sure” and “like/don’t like/not so sure” format.

Part 1 asked what patients thought of the scheme on the whole.

Part 2 presented four statements to which respondents were asked to tick “like it/don’t like it/not so sure”. The statements consisted of the following topics:

- Not having to make an appointment with a GP

- Not having to see a GP to treat a minor illness

- Being able to get medicines free of charge

- Accessing medical advice at the pharmacy

Part 3 asked if respondents would recommend the scheme to someone else and Part 4 asked if they would use the scheme again in the future. If respondents answered “no” to either of these questions they were asked to comment on this. Part 5 presented nine statements to which respondents were asked to indicate their feelings by ticking the options “I agree/I disagree/I’m not so sure”.

Lastly, respondents were asked to make any further comments not covered by the questionnaire.

The PCT’s patient survey group reviewed and approved the questionnaire. It was then sent to the research and ethics committee at Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust for ethical approval but this was deemed not necessary.

To allow the questionnaire to be sent to patients retrospectively by the PCT while ensuring patient confidentiality was not compromised, the questionnaire asked permission for the PCT to use the details on the form for audit and patient satisfaction survey purposes. Patients could either accept or decline by ticking the options “yes” or “no”. Only those patients who ticked “yes” would be sent the questionnaire together with a pre-paid envelope. From 3,642 copy consultation forms returned to the PCT, only 303 forms (8.6 per cent) indicated consent.

Results

A total of 303 forms were sent out and 123 were returned, representing a response rate of 40 per cent. Almost all of the respondents were positive about the scheme. Of 110 respondents who answered the question “what do you think of the scheme overall?”, 76 (69 per cent) said it was excellent and 31 (28 per cent) said it was good. Three respondents (3 per cent) was “not so sure”.

The question “Will you recommend the scheme to someone else?” was answered by 123 respondents. Of this, 120 (98 per cent) said they would. Three respondents said they would not and gave their reasons as no privacy, intrusive questions, unhelpful staff, limited formulary, and the fact that they believed it was a doctor’s prerogative to prescribe.

The question “Will you use the scheme again in the future?” was answered by 122 respondents. All expect one said they would use the scheme again. The reason one respondent would not use the scheme again was that a follow-up GP consultation was needed.

Part 2 of the study showed that respondents liked the scheme because they were now able to obtain free medicines at the pharmacy without recourse to a GP prescription (97 per cent) and because they did not have to make an appointment with the GP (96 per cent). Most respondents appreciated that the scheme now gave them the choice of having their minor ailment treated elsewhere (93 per cent) and they could get medical advice without going to the surgery (88 per cent).

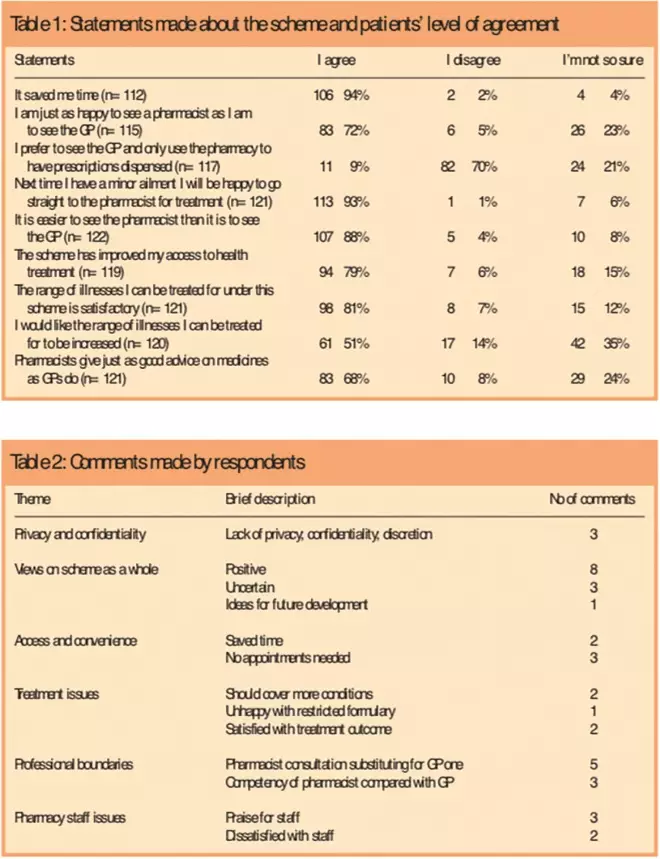

Table 1 shows that most respondents agreed that the scheme saved them time, it was easier to see the pharmacist than the GP and their access to treatment had improved. Where minor ailment treatment and advice on medicines are concerned, around 70 per cent of respondents are equally satisfied with consulting a pharmacist as they would be with consulting their GP. However, almost 25 per cent of respondents expressed uncertainty on these issues. Nevertheless 93 per cent of respondents would return to a pharmacist for treatment of a minor ailment. Although most respondents considered the range of illnesses covered by the scheme satisfactory, half wanted further conditions added.

Almost a third of respondents made comments at the end of the questionnaire; these are detailed in Table 2.

Tables 1 and 2: Statements made about the scheme and patients’ level of agreement; and Comments made by respondents

Discussion

In the first six months 3,642 minor ailment consultations took place. This figure actually represents 2,878 scheme users as many people had accessed the scheme many times over that period. Questionnaires were sent to 303 people and 123 forms were returned. This represents 10.5 per cent and 4.3 per cent of scheme users, respectively. Two reasons, ascertained anecdotally from feedback from community pharmacists, as to why such a small number of scheme users consented to participate in an audit/survey conducted by the PCT were, first, that the “consent to participate” statement is written in small font and located at the bottom of the consultation form and was thus missed on most occasions and, secondly, many people were unsure about committing themselves since it was not clear exactly what participation would involve. In future questionnaires it may be more appropriate to place the “consent to participate” statement at the top of forms in more visible type face. Also some explanation as to what participation would involve (ie, being sent a questionnaire to complete concerning the patient’s experience of the scheme) may result in greater numbers taking part.

Access and convenience

This survey demonstrates that patients have found the MAS to be effective in terms of access and convenience. This is most likely due to there being few barriers to using the scheme. Obtaining medicines free of prescription charge and removing the need to see a GP also facilitated this.

Choice

The intention of MASs is to divert patients away from GP consultations and towards pharmacist consultations for a defined list of ailments. This study illustrates that in terms of preference, consultation with and quality of advice given, most patients are supportive of pharmacists taking the place of GPs in the treatment of minor ailments. This is important in light of the Government’s stated priorities in “Building on the best” and encouraging a choice of providers of health services outlined in “Creating a patient-led NHS”.[9]

An interesting finding revealed by this study is that a significant proportion of people were unsure if a GP consultation could be substituted for one with a pharmacist. There are some possible reasons for this. Patients may find pharmacist consultations less suitable for some symptoms than others.[7]

One respondent commented that a GP consultation is one-to-one but a pharmacy consultation is not, and a second respondent complained that all discussion took place with an assistant and they never saw the pharmacist. If patients are diverted from the surgery to the pharmacy for treatment, they would expect not only to be treated by a health professional of similar standing to their GP but also to be seen in a similar manner. For some patients, therefore, experience of this scheme may have fallen short of their expectations.

Treatment issues

The draft “Care in the pharmacy” scheme originally covered 20 ailments because it mirrored a neighbouring PCT’s list, and it was expected that there would be cross-border reciprocity. However three ailments (eczema, teething and scabies) were removed (for varied reasons) after consultation and agreement with the PCT’s prescribing subcommittee. Since the NPA toolkit recommends to “start small and build incrementally”, it was thought that the range of ailments covered by “Care in the pharmacy” was adequate. However, this study revealed that half of respondents wanted more conditions to be added to the scheme. One respondent wrote that teething, oral thrush, toothache, muscle aches and sprains should be added, although this information was not specifically asked for.

Comments were made in the survey about the limited range of medicines available for treatment. The reason for a restricted formulary was due to medicines suggested for inclusion having to be evidence-based. This information was ascertained using Prodigy and BMJ Clinical Evidence Concise. Hence treatments for conditions such as chesty coughs were not included because there is no evidence base for expectorant use. Also only first-line treatment options were included in the formulary, eg, only clotrimazole cream for the treatment of athlete’s foot.

Issues of professional boundaries may arise in services like the MAS where there may be potential for conflict between two health professionals, or patients may feel confused about which health professional is best suited to provide certain treatments. No anecdotal or hard evidence of conflict between health professionals has so far come to light. One patient was worried that illnesses may be misdiagnosed and another commented that it was up to doctors to decide whether medicines were needed or not. Some patients may well end up seeing their GP due to unresolved illness or because the illness was more serious than first considered. Situations like these will inevitably occur occasionally and cannot be eliminated, eg, a cough can progress to a full-blown upper respiratory tract infection that may require the patient to visit their GP. Evaluation of previous MASs has shown that reconsultation rates with the GP are low — 2.4 per cent within 14 days of a community pharmacy consultation versus 3.8 per cent following a GP consultation.[10]

One comment was made in this study where a parent described that they had to take their child to see a doctor shortly after accessing the MAS. This is one limitation of the study, because it did not ask scheme users if they had subsequently to visit their GP for treatment of the same episode of illness. This would have helped determine the reconsultation rate of this MAS.

Privacy

Traditionally pharmacists and patients interact with each other over the shop counter — conversations are not private and can easily be overheard. This is clearly a limitation of pharmacy-based consultations. The new community pharmacy contract encourages and stipulates that pharmacists need to invest in private consultation areas particularly if they wish to provide advanced services. Most pharmacies within Chorley & South Ribble PCT have private consultation areas and those that do not have plans to install them. This should help towards addressing any privacy and confidentiality concerns patients may have.

Staff

One of the core competencies for providing a minor ailment scheme given in the NPA toolkit states that “the pharmacy will behave in a manner which instills confidence of others involved in the treatment of minor ailments, especially the patient”. Previously the PCT looked into providing customer care skills for pharmacy staff via the NHS University but due to the reorganisation of this institution this was put on hold. It may be worthwhile to look into this again to facilitate better patient-staff interaction.

Concerns raised in this study need to be put into perspective. The fact that almost all respondents indicated they would continue using the scheme, would recommend it to others and appreciate the choice of consulting an alternative health professional for minor ailments shows that there is an undercurrent of positive experience in dealing with pharmacists. The issue of pharmacist-GP substitution possibly warrants further investigation but is outside the scope of this study.

If a similar study was to be conducted again, a future questionnaire should address issues that arose in this one such as reconsultation for same episode of illness, whom the patient was seen by in the pharmacy, suggestions for additional conditions and whether facilities in the pharmacy were sufficiently private for what the patient wanted to discuss.

Conclusions

People who have accessed the MAS found it to be effective in terms of providing rapid and convenient access to advice and treatment. This study will provide the PCT with evidence of patients’ views on accessing novel health services via community pharmacies, and therefore help to inform future service development.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Hazel Hughes, Rukaiya Chand and Wade Syed for their help, advice and encouragement.

This paper was accepted for publication on 28 April 2006

About the author

Samir Vohra, MRPharmS, is community pharmacy development specialist at Chorley & South Ribble Primary Care Trust, Jubilee House, Lancashire Business Park, Centurion Road, Leyland, Lancashire PR1 6UU (e-mail: samir.vohra@chorley-pct.nhs.uk)

References

[1] Department of Health. The NHS plan: a plan for investment, a plan for reform. London: The Department; 2000.

[2] Department of Health. Pharmacy in the future —implementing the NHS plan. London: The Department; 2000.

[3] Proprietary Association of Great Britain. Self care. Available at: www.pagb.org.uk/pagb/primarysections/selfcare/ selfcare.htm (accessed 9 June 2006).

[4] Department of Health. Building the best — choice, responsiveness and equity in the NHS. London: The Stationery Office; 2003.

[5] Department of Health. Our health, our care, our say. A new direction for community services. London: The Department; 2005.

[6] Department of Health. A vision for pharmacy in the new NHS. London: The Department; 2003.

[7] Blenkinsopp A, Noyce PR. Minor illness management in primary care: A review of community pharmacy NHS schemes. Department of Medicines Management, Keele University; 2002.

[8] National Pharmaceutical Association. Implementing a community pharmacy minor ailment scheme. A practical toolkit for primary care organisations and health professional. At Albans: NPA; 2004.

[9] Department of Health. Creating a patient-led NHS — delivering the NHS improvement plan. London; The Department; 2005.

[10] Whittington Z, Hassell K, Cantrill J, Noyce PR, Rogers A. Care at the Chemist: a question of access. A feasibility study comparing community pharmacist and general practice management of minor ailments. School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Manchester; 2001.