Key points:

- Allergic rhinitis occurs in atopic individuals who produce IgE to allergens, such as pollen, house dust mites, animal dander and moulds.

- Histamine stimulates the early symptoms, predominately mucus production, nasal itching and sneezing. This may respond well to non-sedating H1 -antihistamines.

- Subsequent allergic inflammation gives rise to nasal blockage. This responds to nasal steroids.

- When untreated, allergic rhinitis can potentially impair patients’ ability to sleep and perform optimally in their daily professional or personal life. Children’s education is also particularly affected.

- First generation H1 -antihistamines should be avoided because they exacerbate the psychogenic effects of allergic rhinitis.

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is a common allergic disease with increasing prevalence; recent estimates suggest it affects over 30% of individuals, particularly, but not exclusively, teenagers and young adults[1]

,[2]

. While considered by many as a trivial disease, allergic rhinitis, in addition to the nasal and ocular symptoms, is crucially linked to impairments in information processing and changes in attention-related cognitive processes[3]

. However, it has been estimated that up to 90% of allergic rhinitis patients are untreated, insufficiently treated or inappropriately treated[4]

. This has the potential to impair patients’ ability to perform optimally in their daily professional and personal life.

Pathological and psychological effects of untreated allergic rhinitis

Allergic rhinitis generally develops during childhood and it is the most common chronic allergic disorder seen in children[5]

. Studies have shown that these children can experience significant impairment through multiple physical and psychological aspects. Their symptoms, particularly a runny nose, mean that children are often embarrassed in school, have decreased social interaction and are at double the risk of accidental injury[5]

,[6]

. Nasal congestion, in particular, is associated with sleep disturbance and resultant daytime fatigue[7]

. Two studies have concluded that untreated allergic rhinitis has a marked detrimental effect on children’s learning and examination performance[8]

,[9]

. This is particularly important considering that a quarter of UK school-age children suffer with allergic rhinitis[10]

, most of whom will have their peak symptoms in spring and summer, which can coincide with important school examinations. The correlation between allergic rhinitis and negative effects on learning should be an area of concern for all professionals involved in their care.

The overall quality of life reduction resulting from allergic rhinitis in adults is well established – it has a detrimental effect on adult cognitive processes (e.g. productivity at work), as well as other common attention-requiring activities, such as driving[4]

,[11]

,[12]

. In a study assessing the effect of nasal allergen provocation of seasonal allergic patients on driving performance, it was demonstrated that symptomatic and untreated patients had significantly impaired driving ability, the magnitude of which was comparable to having a blood alcohol level of 0.05%, the legal limit in many countries[13]

. In addition to acute symptoms, sleep disturbances may exacerbate impairment of psychomotor performance, including driving[14]

,[15]

,[16]

,[17]

. Patients with allergic rhinitis are often affected by physical conditions (e.g. otitis media, eustachian tube dysfunction, sinusitis[18]

) and other allergic conditions (e.g. asthma and eczema[19]

). Therefore, allergic rhinitis is an illness that affects multiple aspects of patient’s life[19]

, can be a source of multiple doctor appointments and has complex effects on society as a whole. Therefore, optimal management of the disease should address both its physical and mental consequences.

Mechanisms of allergic rhinitis

The roots of allergy are in parasitology, when a nematode parasite attacking the nasal mucosa. On first presentation, the immune system is stimulated to produce immunoglobulin E (IgE) that will bind to and prime mast cells and other inflammatory cells. On a subsequent presentation, nematode antigens interact with the mast cell IgE, causing it to release preformed histamine to make the local environment hostile (e.g. producing mucus and stimulating sensory nerves to cause sneezing). Mast cells also produce cytokines to stimulate the influx inflammatory cells, particularly eosinophils that contain several toxic proteins with which they kill the nematode and cause local inflammation. Patients with allergies mount the same response to allergens as nematode antigens[20]

,[21]

. The series of early immune system events in patients with allergic rhinitis is presented in Figure 1.

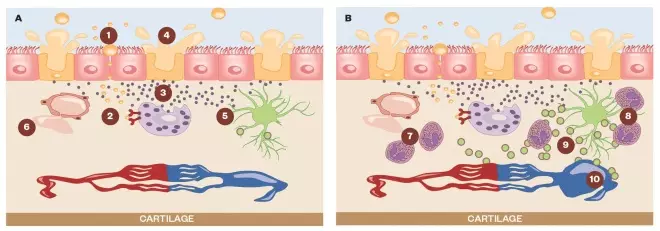

Figure 1: Immune system events in patients with allergic rhinitis

Panel A demonstrates early immune system events, while panel B shows the later inflammatory allergic response that increases the severity and persistence of the initial symptoms in patients with allergic rhinitis. See text for an explanation of the events (numbered).

Panel A demonstrates (1) allergens (e.g. pollen, house dust mites, animal dander and moulds) penetrating the nasal epithelium. (2) Allergen interacts with IgE, shown in red, to activate the mast cell. (3) Histamine is the primary mediator released in this early phase of the response. It has three immediate main effects: (4) stimulation of mucosal goblet cells to produce watery mucus; (5) stimulation of sensory nerves to cause nasal itching and sneezing; and (6) vasodilation and tissue oedema, which contribute to nasal blockage. These effects are primarily histamine-mediated so antihistamines are effective in relieving these symptoms.

Panel B shows the later inflammatory allergic response that increases the severity and persistence of the initial symptoms, resulting in a chronic phase of allergic rhinitis. Mast cell activation also produces cytokines, responsible for the attraction of more mast cells and the influx and activation of other inflammatory cells, particularly eosinophils (7)[22]

. Eosinophils contain aggressive proteinaceous mediators (8) that stimulate sensory neurones to dramatically increase the production and release of neuropeptides (9). These neuropeptides act on special venous capacitance vessels (10) present in the nasal turbinates, causing dilatation and reduced emptying. This is the primary cause of nasal blockage.

Mechanisms of ocular symptoms

Patients with allergic rhinitis may also experience ocular symptoms, primarily reddened, itchy and watery eyes. Classically these symptoms were believed to be caused by the allergen landing on the conjunctival lining of the eye, with subsequent activation of the conjunctival mast cells[23]

. It is now believed that these symptoms are partly the result of a naso-ocular reflex in which allergic inflammation in the nose stimulates the trigeminal nerve with subsequent release of neuropeptides in the tears[24]

. These neuropeptides activate conjunctival mast cells that release histamine but cause little subsequent eosinophil infiltration and allergic inflammation[23]

. During periods of high atmospheric levels, pollen impaction on the conjunctiva may induce a more severe form of vernal conjunctivitis in which eosinophil infiltration stimulated allergic inflammation[25]

. If a severe form of vernal conjunctivitis is suspected, the patient should be referred to their GP.

Diagnosis of allergic rhinitis by pharmacists

Historically, diagnosis of allergic rhinitis has been made by primary healthcare practitioners. However, pharmacists are now being encouraged to make the primary diagnosis of allergic rhinitis and establish a management and therapy plan[26]

. Although it should be emphasised that complex cases, or cases where there may by an alternative diagnosis, should always be referred to a GP.

Allergic rhinitis symptoms, including runny nose, itching, sneezing and nasal blockage, are similar to those of the common cold and can be present intermittently, giving the false suggestion of recurrent ‘colds’[27]

. This is more common in patients who are allergic to pollens or outdoor moulds (rather than pets or house dust mites), which are released into the air and cause symptoms during specific periods of time throughout the year (see ‘Figure 2: Seasonal considerations’).

Taking a history from the patient

When questioning the patient, pharmacists should listen for indicators that can lead to the diagnosis of allergic rhinitis, for example:

- recurrence at a particular time of year or day, or variability of symptoms, suggesting worsening on exposure to the relevant allergen;

- involvement of the eyes (itching, watering, redness, puffiness); or

- predominance of itch as a symptom, which can also involve the pharynx and ears.

- Allergic rhinitis is more likely if there is a past or family history of allergic disease, but can also occur as the first manifestation of allergy in a previously unaffected person.

When taking the patient’s history, it is important to be aware that they might not often offer all the clues for diagnosis, so pharmacists may have to ask specific questions to find out more information. For example, a patient with allergy to house dust mites or animals may complain of sneezing, having a runny nose and blocked nose in the past one or two weeks, but they might not realise until asked that their nose has been blocked to a less severe degree for a much longer time. The pharmacist should also enquire about new allergens in the home, work, or school environment, as well as symptoms of asthma (shortness of breath accompanied by wheeze, reduced exercise tolerance or nocturnal symptoms), which often accompany poorly controlled allergic rhinitis.

Seasonal considerations

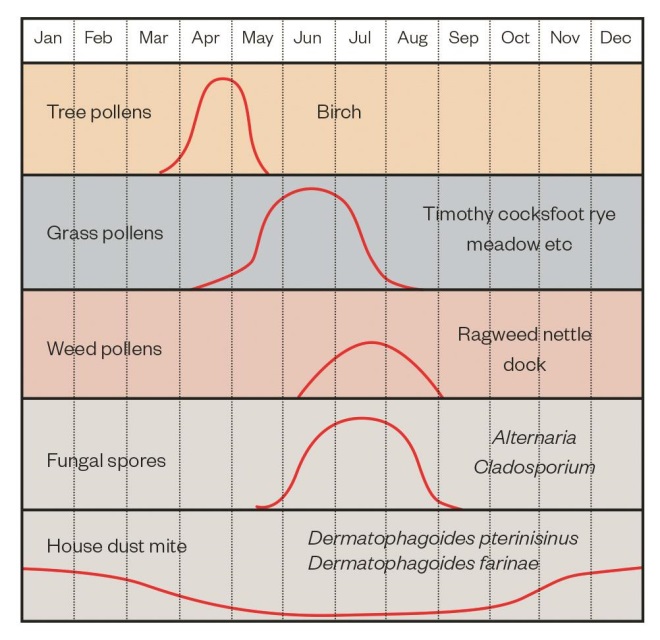

Figure 2: The seasons of major plant allergens and house dust mite

The lines refer to the times of year at which different allergens peak. Note that house dust mite levels are highest in the winter when doors and windows are closed in centrally heated homes.

Patients may be allergic to trees, plants and fungi that use the wind to disperse their pollen or spores[28]

. Higher amounts of pollens are released during dry, warmer days when the chance of their satisfactory dispersion is maximum (see Figure 2). Visually these plants are unspectacular in contrast to those with colourful flowers to attract bees and other insects to cross-pollinate them. Individuals are rarely allergic to this latter type[28]

.

While high amounts of pollen and fungal spores are released during warmer days compared to colder ones, house dust mite allergens are present all year round. However, these tend to be higher indoors during winter when windows are shut and the humid, centrally heated atmosphere is optimum for their reproduction[29]

.

Further testing

With a clear patient history, diagnosis can be made without further tests. However, if in doubt, looking for the likely IgE molecules by skin prick or blood test can be helpful, although this should be guided by history, rather than performed in a random fashion. Random screening of multiple possible allergens is inadvisable because positive tests do not always indicate clinical disease; many individuals with allergen-specific IgE do not develop symptoms[30]

. Furthermore, a positive test to an allergen with no pertinence to patient’s history has no relevance for diagnosis and might result in over-diagnosis and unnecessary stress for the patient. Testing should always be considered in the context of the possible clinical benefit, which can be from allergen avoidance, if the patient is able and willing to comply, or allergen specific immunotherapy.

Treatment

This section assesses the drugs only briefly – further information and the British Society for Allergy & Clinical Immunology (BSACI) guidelines for the management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis[31]

are included in later sections.

H1 -antihistamines are effective in relieving histamine-induced symptoms, including itch, runny nose and/or sneezing[31]

. They have a lesser effect on nasal blockage but can be effective as a single medicine in patients with mild to moderate forms of allergic rhinitis[31]

. They have a rapid onset of action and can be used as a rescue medicine to help alleviate the symptoms of the onset of acute allergic rhinitis.

Intranasal corticosteroids are the primary treatment for nasal obstruction[31]

and act by reducing cytokine production thereby reducing eosinophil recruitment. They also reduce eosinophil activation and mediator release[32]

.

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRAs)

are

given as tablets and may be effective in some patients but not all[33]

. They reduce the effects of the leukotriene C4 (LTC4) that activated mast cells and eosinophils secrete in order to enhance the recruitment of more eosinophils and thereby reduce allergic inflammation[34]

. The LTRAs montelukast and zafirlukast are available on medical prescription only (POM). Leukotriene synthesis inhibitors (e.g. zileuton), are not available in the UK.

Nasal decongestants (e.g. xylometazoline and oxymetazoline), are asympathetic receptor stimulants and cause constriction of the arterial vessels delivering blood to the nasal capacitance vessels, therefore starving them of blood[35]

. They may be given locally or orally. When given as nasal drops, they are briefly effective and rapidly acting but they may only be used for short periods – usually four to ten days[31]

. Regular use induces a decrease in the number of a-receptors in the blood vessels rendering a reduced effectiveness with time (tolerance)[35]

. If used for longer periods, rhinitis medicamentosa, a condition characterised by nasal congestion without rhinorrhoea or sneezing, may occur because of a reduction of blood vessel a-receptors thus paralysing the physiological local vasoconstriction process[7]

. Patients should be counselled regarding this process.

Oral decongestants (e.g. pseudoephedrine) are only weakly effective in reducing nasal obstruction but have a longer duration of up to six hours (with slow release preparations)[31]

. Owing to their sympathomimetic effects, they should not be used by individuals with high blood pressure or heart problems[36]

.

Saline douching, although relatively uncommon in UK, is a safe and inexpensive method of reducing symptoms in children and adults with seasonal rhinitis by washing out sticky mucus from the nose[31]

.

The treatment of ocular symptoms of allergic rhinitis is summarised in Box 1.

Box 1: Treatment of ocular symptoms

- Intranasal corticosteroids

are the most effective treatment for reducing nasal inflammation and, consequently, are effective in improving conjunctival symptoms[37]

. - H1-antihistamine eye drops have a similar efficacy profile to oral antihistamines with the advantage of a significantly faster onset of action[38]

. - Topical chromones, sodium cromoglycate or nedocromil sodium,

which are available as topical eye preparations, are also weakly effective. Although purported to be mast cell stabilisers, they most likely affect the inhibition of sensory nerve activation, thereby reducing itching[39]

.

Selecting the right treatment

Oral antihistamines are the first-line treatment used by most patients, doctors and pharmacists for all allergic rhinitis.

When selecting the most appropriate antihistamine to manage allergic rhinitis, healthcare professionals should be aware of the significant detrimental effect of first generation antihistamines (FGAH) on cognitive processes in all patient groups[40]

. Histamine acting on H1 -receptors in the brain has a completely different function to that in the periphery. In the brain, it has an arousal effect and aids concentration and learning[40]

. FGAHs (e.g. chlorpheniramine, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine and ketotifen) readily penetrate into the central nervous system (CNS) and bind to the H1 -receptors in the brain, causing drowsiness and poor attention[40]

.

Studies in children have demonstrated that FGAHs exacerbate the detrimental effect of allergic rhinitis on learning ability[8]

. Furthermore, in teenagers sitting summer mock GCSE examinations, untreated allergic rhinitis caused a 40% increased likelihood of students dropping an examination grade. FGAHs increased this to 70%[9]

.

In adults the detrimental effects of allergic rhinitis on quality of life and productivity at work are exacerbated by FGAHs, even at the lowest doses recommended by manufacturers[40]

. The effects of FGAHs on the CNS are similar to and additive with those produced by alcohol or other CNS-sedatives, and bedtime dosing with FGAHs may have hangover effects the next day due to their long elimination half-life value[40]

. Furthermore, FGAHs may significantly reduce driving ability to potentially dangerous levels[40]

,[41]

, particularly in the elderly and those who combine the drug with alcohol ingestion. One study suggests that 25% of individuals older than 65 years of age have some cognitive impairment, often with no overt sign of dysfunction[42]

. Administration of FGAHs to this population increases the risk of inattention, disorganised speech, altered consciousness and impaired function or alertness[43]

,[44]

. In addition, because of their anticholinergic activity, FGAHs significantly increase the risk for development of dementia[45]

.

Therefore, the British and European Guidelines for both allergic rhinitis and urticaria specify that only second generation antihistamines should be used for symptom relief, because they penetrate less well into the brain than FGAHs and have negligible anticholinergic effects[31]

,[46]

. In the UK, cetirizine and loratadine are currently the only SGAHs available for patients to buy over-the-counter (OTC). There are many others (including levocetirizine, desloratadine, rupatadine, fexofenadine and bilastine) that are available as prescription-only medicines (POM). Even though SGAHs are stated to be minimally sedating, there are some patients who suffer sedation and psychomotor retardation, especially if other sedatives or alcohol are taken concomitantly[40]

. Fexofenadine and bilastine are the least sedating SGAHs currently available because they are actively pumped out of the blood–brain barrier by p-glycoprotein (a proton pump)[47]

. However, these must be taken on an empty stomach for adequate absorption.

Intranasal antihistamines are more effective at reducing nasal symptoms than oral antihistamines, but do not treat extra-nasal symptoms[48]

. Azelastine nasal spray is available OTC.

Although antihistamines demonstrate efficacy, for the control of symptoms like sneezing, itching and rhinorrhoea or eye streaming, they are considerably less effective than intranasal corticosteroids that have a much stronger anti-inflammatory effect and are more effective in treating nasal obstruction[49]

. Corticosteroids should be used as the therapeutic of choice for anything more than mild disease[31]

.

Intranasal steroids

Intranasal steroids are the most effective treatment for reducing nasal inflammation and improving conjunctival symptoms[23]

,[50]

. In the UK, beclomethasone dipropionate and fluticasone propionate are available OTC, while fluticasone furoate and mometasone furoate are POM.

When bought OTC or even when prescribed by a medical practitioner, nasal steroids are often wrongly used or not used at all, because of fears of “steroids”. Therefore, it is important to explain to the patient that the dose of nasal steroids is in microgram quantities and for most of the common molecules there is minimal systemic bioavailability (i.e. the amount of active drug reaching the systemic circulation). There is a variation between molecules, with fluticasone propionate, furoate and mometasone furoate being the least bioavailable from the nose. It is best to use the spray in the morning, putting it next to the toothbrush to aid memory. A second dose can be used in the evening if needed, or if the morning one was forgotten.

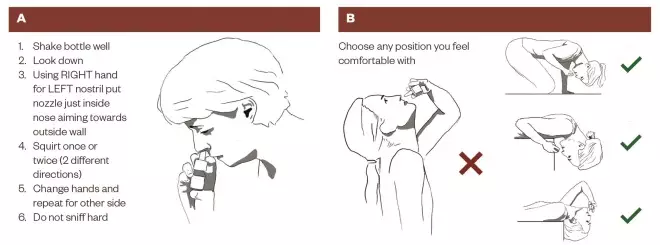

The method of application for nasal sprays and drops is shown in Figure 3. Spraying the nasal septum and sniffing the spray straight back into the throat should be avoided.

Figure 3: Method of application for nasal sprays and nasal drops

Source: Reproduced from the BSACI allergic rhinitis guidelines with permission.

(a) Correct procedure for the application of nasal sprays. (b) Correct procedure for the installation of nasal drops.

Begin treatment early and take it daily

It is important to inform patients that nasal steroids do not work immediately. Nasal steroids have been shown to take at least several days to reach full effectiveness and maximal effect may not be apparent for two weeks[29]

.

For patients with intermittent symptoms (e.g. those allergic to pollens) it has been demonstrated that if therapy with topical nasal corticosteroids is begun a week or two before symptoms are expected, symptoms have delayed onset and reduced severity[51]

. Thus, it can be useful to ask patients with known seasonal allergic rhinitis to make a note of when their symptoms started in the current year so that in the following year they can start the treatment earlier.

Similarly, both antihistamines and nasal corticosteroids, particularly the latter, are more effective if used on a daily basis, rather than being stopped and started[51]

. The symptoms for both persistent and intermittent allergic rhinitis are underlined by an ongoing inflammation that is usually present at subclinical levels, even in the absence of symptoms[52]

. Daily treatment helps to prevent this low-grade ongoing subclinical allergic inflammation in the nasal lining increasing to a threshold at which symptoms occur and, thus, reduces the rate and severity of exacerbations[51]

. Therefore, pharmacists should explain to patients that the drug makes them free of symptoms, rather than curing their disease, so stopping treatment early will result in the reappearance of symptoms. If they do not get relief from the prescribed medication, they should seek further advice since other treatment options might be available.

A simple way to keep track of patients’ symptoms is for them to use the MACVIA-ARIA visual analogue scale, via a mobile phone app[53]

. If their total symptom score is over half way along the line, the treatment needs to be augmented or changed. Switching from one brand of antihistamine or intranasal corticosteroid to another is not the answer.

BSACI guidelines suggest that in more severe disease nasal corticosteroids and antihistamines may be used together[31]

and the combination of nasal corticosteroid plus nasal antihistamine (e.g. azelastine plus fluticasone) has been reported to be more effective than either alone[54]

,[55]

. However, this drug combination is a POM at present.

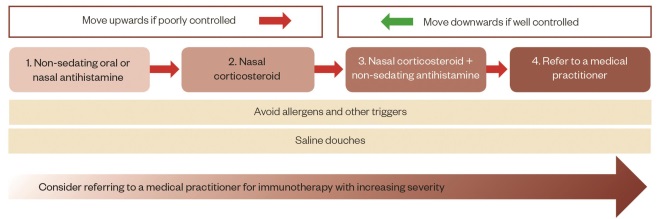

Management of allergic rhinitis

The BSACI guidelines provide direction to help healthcare professionals direct therapy for allergic rhinitis[31]

. A simple algorithm for the treatment of allergic rhinitis is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: A simple algorithm for the treatment of allergic rhinitis

Source: This figure is adapted from the BSACI allergic rhinitis guidelines.

The progression of treatment goes from left to right as severity increases.

For patients with intermittent allergic rhinitis caused by seasonal allergens, as the season wanes and pollen levels in the atmosphere reduce, treatment can be gradually reduced, if the symptoms are completely controlled, and stopped once the season is over.

Patients with persistent allergic rhinitis, such as those allergic to perennial allergens (e.g. house dust mite, animals or indoor moulds) or those with mixed seasonal and perennial allergies, need longer term therapy. Once complete control of symptoms has been achieved, a gradual ‘step down’ can be attempted. The treatment should be continued for at least three to six months after complete symptom control. If symptoms recur, the treatment should be restarted, usually for longer periods (e.g. 6–12 months or even for life). There are some concerns about possible lining atrophy with long-term use of intranasal steroids. However, in practice, with correct use this does not occur, probably because of rapid movement by mucocilliary clearance[56]

. Spraying the nasal septum repeatedly can result in soreness, epistaxis (nose bleed) and possibly even perforation, which is why correct technique is important.

Allergen avoidance

Studies involving concomitant multiple strict allergen control measures showed that it is possible to achieve a significant reduction in allergen exposure and, consequently, in symptoms[57]

,[58]

. However, in real life situations, avoiding aeroallergens to an extent where it would make a difference in patients’ symptoms is difficult to reach. With pollen allergy, closing windows at night, driving with closed windows or wearing wrap-around glasses outdoors can prevent symptom exacerbation[31]

. Avoiding being outside during thunderstorms can also help reduce symptoms, because the sudden change from a dry to a wet climate causes pollen grains to rupture and release their allergenic into smaller particles, which can be easily inhaled into the lower airways and cause attacks of allergic rhinitis and asthma[59]

.

Immunotherapy

Allergen-specific immunotherapy is the treatment in which a patient’s immune system is rendered tolerant to an allergen by giving increasing doses of the allergen in a controlled fashion[60]

,[61]

. When used correctly, it is the only treatment that can alter disease course[60]

. There is also evidence that it can reduce development of further sensitisations and progression of allergic rhinitis to asthma, although current trials require positive outcomes to determine if children with allergic rhinitis, who are likely to progress to asthma, will benefit from it[61]

.

Few seasonal allergic rhinitis patients warrant immunotherapy treatment; it should only be considered when allergic rhinitis is debilitating and poorly controlled by pharmacotherapy. Special consideration should be given to badly affected young people who face years of summertime examinations or adults whose functioning is disturbed (e.g. surgeons who have severe eye symptoms or sneezing bouts)[61]

. Immunotherapy is currently available for allergic rhinitis caused by pollen, moulds, house dust mite and animal allergens.

There are two main routes by which immunotherapy is administered; subcutaneously and sublingually. Subcutaneous immunotherapy involves allergen injections at regular time intervals in a hospital by trained medical staff. With treatment lasting several years, patient commitment to attending hospital appointments is essential. Sublingual immunotherapy is considered to be much safer. The initial dose is given under supervision, but can then be continued on a daily basis at home[62]

,[63]

. However, patients should be warned against poor compliance, which is a concern with this form of immunotherapy[64]

.

Management in specific patient groups

Children with allergic rhinitis

Children metabolise drugs less well than adults because the liver enzymes mature slowly and only reach maximal levels at around ten years of age[65]

. However, renal clearance is well developed. Consequently, it is preferable that young children are prescribed an antihistamine that is not metabolised but excreted unchanged in the urine[66]

. Of the OTC preparations, this means cetirizine is preferable, rather than loratadine.

A nasal steroid with low systemic bioavailability should be used at the lowest possible dose to control symptoms, particularly nasal congestion and obstruction. Compliance and efficacy is improved if the child is taught how to use the nasal spray[31]

. In older children where liver metabolic enzymes are increasing, it may be preferable to use fluticasone, which is cleared by first metabolism, rather than beclomethasone that is not and, consequently, may accumulate[67]

. Furthermore, fluticasone is available for children from four years of age, while beclomethasone is only available for children from six years of age.

Allergic rhinitis in pregnancy

Most medicines cross the placenta, and should only be prescribed when the apparent benefit is greater than the risk to the foetus[31]

. Regular nasal douching may be helpful. Of the antihistamines, both loratadine and cetirizine are recommended because they appear to have good safety records because they have been widely used in pregnant women[68]

. Similarly, beclomethasone and fluticasone appear safe. However, decongestants should be avoided[31]

. Local application of chromones, which have not demonstrated teratogenic effects in animals, are probably the safest drug choice for use in the first three months of pregnancy because systemic absorption is negligible, although they require multiple daily administrations[31]

.

Conclusion

The treatment of allergic rhinitis involves non-sedating H1 -antihistamines to reduce rhinorrhoea and nasal itching, and corticosteroids to reduce allergic inflammation and nasal blockage. They should be used on a daily basis rather than on ad hoc when symptoms are bad. Pharmacists should advise patients about how to correctly administer their treatment, as well as reviewing its effectiveness regularly. Patients should be advised of alternative treatment options where appropriate.

Diana S Church is general practitioner at Bath Lodge Practice at Bitterne Health Centre, Southampton. Martin K Church is professor, Department of Dermatology and Allergy at Allergie-Centrum-Charité, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Glenis K Scadding is honorary consultant physician in allergy and rhinology, Department of Allergy and Medical Rhinology at the Royal National Throat Nose and Ear Hospital, London. Correspondence to:

mkc@soton.ac.uk

Financial and conflicts of interests dislosure:

Martin Church has been a speaker or consultant for Almirall, FAES Pharma, Menarini, Moxie, MSD, Novartis, UCB Pharma, Sanofi-Aventis and Uriach. Glenis Scadding has had research grants from GSK & ALK and has been a speaker or consultant for ALK, Astra Zeneca, Brittania Pharmaceuticals, Capnia, Church & Dwight, Circassia, GSK, Groupo Uriach, Meda, Merck, MSD, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Oxford Therapeutics, Sanofi-Aventis, UCB. Diana Church has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. No writing assistance was utilised in the production of this manuscript.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] Bjerg A, Ekerljung L, Middelveld R et al. Increased prevalence of symptoms of rhinitis but not of asthma between 1990 and 2008 in Swedish adults: comparisons of the ECRHS and GA(2)LEN surveys. PLoS One 2011;6(2):e16082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016082

[2] Maio S, Baldacci S, Carrozzi L et al. Respiratory symptoms/diseases prevalence is still increasing: a 25-yr population study. Respir Med 2016;110:58-65. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.11.006

[3] Trikojat K, Buske-Kirschbaum A, Schmitt J et al. Altered performance in attention tasks in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis: seasonal dependency and association with disease characteristics. Psychol Med 2015;45(6):1289-1299. doi: 10.1017/S0033291714002384

[4] Zuberbier T, Lotvall J, Simoens S et al. Economic burden of inadequate management of allergic diseases in the European Union: a GA(2) LEN review. Allergy 2014;69(10):1275-1279. doi: 10.1111/all.12470

[5] Garg N, Silverberg JI. Association between childhood allergic disease, psychological comorbidity, and injury requiring medical attention. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2014;112(6):525-532. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.03.006

[6] Mir E, Panjabi C, Shah A. Impact of allergic rhinitis in school going children. Asia Pac Allergy 2012;2(2):93-100. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2012.2.2.93

[7] Scadding G. Optimal management of nasal congestion caused by allergic rhinitis in children: safety and efficacy of medical treatments. Paediatr Drugs 2008;10(3):151-162. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200810030-00004

[8] Vuurman EF, van Veggel LM, Uiterwijk MM et al. Seasonal allergic rhinitis and antihistamine effects on children’s learning. Ann Allergy 1993;71(2):121-126. doi: 10.1016/0924-977X(92)90101-D

[9] Walker S, Khan-Wasti S, Fletcher M et al. Seasonal allergic rhinitis is associated with a detrimental effect on examination performance in United Kingdom teenagers: case-control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120(2):381-387. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.03.034

[10] Muraro A, Clark A, Beyer K et al. The management of the allergic child at school: EAACI/GA2LEN Task Force on the allergic child at school. Allergy 2010;65(6):681-689. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2010.02343.x

[11] Meltzer EO, Gross GN, Katial R et al. Allergic rhinitis substantially impacts patient quality of life: findings from the Nasal Allergy Survey Assessing Limitations. J Fam Pract 2012;61(2 Suppl):S5-10. PMID: 22312622

[12] Price D, Scadding G, Ryan D et al. The hidden burden of adult allergic rhinitis: UK healthcare resource utilisation survey. Clin Transl Allergy 2015;5:39. doi: 10.1186/s13601-015-0083-6

[13] Vuurman EF, Vuurman LL, Lutgens I et al. Allergic rhinitis is a risk factor for traffic safety. Allergy 2014;69(7):906-912. doi: 10.1111/all.12418

[14] Pilcher JJ & Huffcutt AI. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep 1996;19(4):318-326. PMID: 8776790

[15] Smolensky MH, Di Milia L, Ohayon MM et al. Sleep disorders, medical conditions, and road accident risk. Accid Anal Prev 2011;43(2):533-548. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.12.004

[16] Kremer B, den Hartog HM & Jolles J. Relationship between allergic rhinitis, disturbed cognitive functions and psychological well-being. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32(9):1310-1315. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2002.01483.x

[17] Zuberbier T & Church MK. Untreated allergic rhinitis is a major risk factor contributing to motorcar accidents [submitted]. 2016.

[18] Hellings PW & Fokkens WJ. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on otorhinolaryngology. Allergy 2006;61(6):656-664. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01109.x

[19] Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Samolinski B et al. Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA): achievements in 10 years and future needs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130(5):1049-1062. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.053

[20] Kay AB. Eosinophils: role in asthma, allergy and parasite immunity. N Engl Reg Allergy Proc 1985;6(4):341-345. doi: 10.2500/108854185779109098

[21] Puxeddu I, Piliponsky AM, Bachelet I et al. Mast cells in allergy and beyond. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2003;35(12):1601-1607. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00208-5

[22] Westergren VS, Wilson SJ, Penrose JF et al. Nasal mucosal expression of the leukotriene and prostanoid pathways in seasonal and perennial allergic rhinitis.Clin Exp Allergy 2009;39(6):820-828. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03223.x

[23] Baroody FM, Foster KA, Markaryan A et al. Nasal ocular reflexes and eye symptoms in patients with allergic rhinitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2008;100(3):194-199. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60442-5

[24] Callebaut I, Vandewalle E, Hox V et al. Nasal corticosteroid treatment reduces substance P levels in tear fluid in allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012;109(2):141-146. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2012.06.008

[25] McGill JI, Holgate ST, Church MK et al. Allergic eye disease mechanisms. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82(10):1203-1214. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.10.1203

[26] NHS Choices. Allergic Rhinitis. 2016. Available at: http://wwwnhsuk/conditions/rhinitis—allergic/pages/introductionaspx (accessed August 2016).

[27] Hellings PW & Hens G. Rhinosinusitis and the lower airways. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2009;29(4):733-740. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2009.08.001

[28] Lohmiller G. Blowing in the wind:allergies and pollen. 2016. Available at: www.almanac.com (accessed August 2016).

[29] Gelardi M, Peroni DG, Incorvaia C et al. Seasonal changes in nasal cytology in mite-allergic patients. J Inflamm Res 2014;7:39-44. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S54581

[30] Bousquet J, Anto JM, Bachert C et al. Factors responsible for differences between asymptomatic subjects and patients presenting an IgE sensitization to allergens. A GA2LEN project. Allergy 2006;61(6):671-680. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01048.x

[31] Scadding GK, Durham SR, Mirakian R et al. BSACI guidelines for the management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2008;38(1):19-42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02888.x

[32] Leung DY. Molecular basis of allergic diseases. Mol Genet Metab 1998;63(3):157-167. doi: 10.1006/mgme.1998.2682

[33] Sampson AP, Siddiqui S, Buchanan D et al. Variant LTC(4) synthase allele modifies cysteinyl leukotriene synthesis in eosinophils and predicts clinical response to zafirlukast. Thorax 2000;55 Suppl 2:S28-S31. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.suppl_2.S28

[34] Fregonese L, Silvestri M, Sabatini F et al. Cysteinyl leukotrienes induce human eosinophil locomotion and adhesion molecule expression via a CysLT1 receptor-mediated mechanism. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32(5):745-750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2002.01384.x

[35] Malm L. Pharmacological background to decongesting and anti-inflammatory treatment of rhinitis and sinusitis. Acta Otolaryngol 1994;515:53-55; discussion 55-56. doi: 10.3109/00016489409124325

[36] Cantu C, Arauz A, Murillo-Bonilla LM et al. Stroke associated with sympathomimetics contained in over-the-counter cough and cold drugs. Stroke 2003;34(7):1667-1672. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000075293.45936.FA

[37] Baroody FM & Naclerio RM. Nasal-ocular reflexes and their role in the management of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis with intranasal steroids. World Allergy Organ J 2011;4(1 Suppl):S1-5. doi: 10.1097/WOX.0b013e3181f32dcd

[38] van Cauwenberge P, Bachert C, Passalacqua G et al. Consensus statement on the treatment of allergic rhinitis. European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. Allergy 2000;55(2):116-134. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00526.x

[39] Willis EF, Clough GF & Church MK. Investigation into the mechanisms by which nedocromil sodium, frusemide and bumetanide inhibit the histamine-induced itch and flare response in human skin in vivo. Clin Exp Allergy 2004;34(3):450-455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01898.x

[40] Church MK, Maurer M, Simons FE et al. Risk of first-generation H(1)-antihistamines: a GA(2)LEN position paper. Allergy 2010;65(4):459-466. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02325.x

[41] Verster JC, Volkerts ER. Antihistamines and driving ability: evidence from on-the-road driving studies during normal traffic. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2004;92(3):294-303; quiz 303-295,355. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)61566-9

[42] Graham JE, Rockwood K, Beattie BL et al. Prevalence and severity of cognitive impairment with and without dementia in an elderly population. Lancet 1997;349(9068):1793-1796. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01007-6

[43] Agostini JV, Leo-Summers LS & Inouye SK. Cognitive and other adverse effects of diphenhydramine use in hospitalized older patients. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(17):2091-2097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.17.2091

[44] McEvoy LK, Smith ME, Fordyce M et al. Characterizing impaired functional alertness from diphenhydramine in the elderly with performance and neurophysiologic measures. Sleep 2006;29(7):957-966. PMID: 16895264

[45] Gray SL, Anderson ML, Dublin S et al. Cumulative use of strong anticholinergics and incident dementia: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(3):401-407. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7663

[46] Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C et al. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: management of urticaria. Allergy 2009;64(10):1427-1443. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02178.x

[47] Church MK. Safety and efficacy of bilastine: a new H(1)-antihistamine for the treatment of allergic rhinoconjunctivitis and urticaria. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2011;10(5):779-793. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2011.604029

[48] Horak F. Effectiveness of twice daily azelastine nasal spray in patients with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2008;4(5):1009-1022. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S3229

[49] Leurs R, Church MK & Taglialatela M. H1-antihistamines: inverse agonism, anti-inflammatory actions and cardiac effects. Clin Exp Allergy 2002;32(4):489-498. doi: 10.146/j.0954-7894.2002.01314.x

[50] Baroody FM, Logothetis H, Vishwanath S et al. Effect of intranasal fluticasone furoate and intraocular olopatadine on nasal and ocular allergen-induced symptoms. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2013;27(1):48-53. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3841

[51] Laekeman G, Simoens S, Buffels J et al. Continuous versus on-demand pharmacotherapy of allergic rhinitis: evidence and practice. Respir Med 2010;104(5):615-625. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.01.006

[52] Ciprandi G, Buscaglia S, Pesce G et al. Minimal persistent inflammation is present at mucosal level in patients with asymptomatic rhinitis and mite allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;96(6 Pt 1):971-979. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70235-0

[53] Bousquet J, Schunemann HJ, Fonseca Jet al. MACVIA-ARIA Sentinel NetworK for allergic rhinitis (MASK-rhinitis): the new generation guideline implementation. Allergy 2015;70(11):1372-1392. doi: 10.1111/all.12686

[54] Carr W, Bernstein J, Lieberman P et al. A novel intranasal therapy of azelastine with fluticasone for the treatment of allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;129(5):1282-1289 e1210. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.01.077

[55] Berger W, Bousquet J, Fox AT et al. MP-AzeFlu is more effective than fluticasone propionate for the treatment of allergic rhinitis in children. Allergy 2016;10.1111/all.12903. doi: 10.1111/all.12903

[56] Verkerk MM, Bhatia D, Rimmer J et al. Intranasal steroids and the myth of mucosal atrophy: a systematic review of original histological assessments. Am J Rhinol Allergy 2015;29(1):3-18. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2015.29.4111

[57] Arshad SH, Bateman B, Sadeghnejad Aet al. Prevention of allergic disease during childhood by allergen avoidance: the Isle of Wight prevention study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119(2):307-313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.621

[58] Lau S. Allergen avoidance as primary prevention: con. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2005;28(1):17-23. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:1:017

[59] D’Amato G, Vitale C, D’Amato M et al. Thunderstorm related asthma: what happens and why. Clin Exp Allergy 2016;10.1111/cea.12709. doi: 10.1111/cea.12709

[60] Scadding G & Durham S. Mechanisms of sublingual immunotherapy. J Asthma 2009;46(4):322-334. doi: 10.1080/02770900902785729

[61] Cappella A & Durham SR. Allergen immunotherapy for allergic respiratory diseases.Hum Vaccin Immunother 2012;8(10):1499-1512. doi: 10.4161/hv.21629

[62] Dahl R, Kapp A, Colombo G et al. Efficacy and safety of sublingual immunotherapy with grass allergen tablets for seasonal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;118(2):434-440. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.05.003

[63] Durham SR & Riis B. Grass allergen tablet immunotherapy relieves individual seasonal eye and nasal symptoms, including nasal blockage. Allergy 2007;62(8):954-957. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01402.x

[64] Malet A, Azpeitia A, Gutierrez D et al. Comprehensive Study of Patients’ Compliance with Sublingual Immunotherapy in House Dust Mite Perennial Allergic Rhinitis. Adv Ther 2016;10.1007/s12325-016-0347-0. doi: 10.1007/s12325-016-0347-0

[65] Kearns GL, Abdel-Rahman SM, Alander SWet al. Developmental pharmacology–drug disposition, action, and therapy in infants and children. N Engl J Med 2003;349(12):1157-1167. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035092

[66] Strolin Benedetti M, Whomsley R & Baltes EL. Differences in absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of xenobiotics between the paediatric and adult populations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2005;1(3):447-471. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.3.447

[67] Allen DB. Do intranasal corticosteroids affect childhood growth? Allergy 2000;55 Suppl 62:15-18. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2000.00704.x

[68] Anon. Allergic rhinitis during pregnancy. Prescrire Int 2016;25(170):101-102. PMID: 27186624