Abstract

In recent years, many government-led initiatives in the UK have been introduced to expand the services provided by community pharmacy (CP) to the public, including for children and young people. The aim of this review is to provide an insight into parents’ and young people’s perspectives on using CP services for child-related matters. A systematic review using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases was conducted to identify original studies published between 2009 and 2019 that examined views and experiences of parents and young people using CPs. A total of five studies were identified; however, none of these considered young people’s opinions on their use of CP. In this review, parent’s perceptions of healthcare professionals consulted for advice and information for a child-related health matter are discussed, alongside their approach to managing their child’s minor ailment. This review concludes that parents, carers and young people are not fully benefitting from the various services that CP can provide for children. This might be attributed to their lack of awareness of services CP offers for children, as well as their lack of trust in pharmacists’ capabilities compared to other healthcare professionals.

More research is needed to identify ways that could help raise the CP profile with regards to children’s services and to devise evidence-based paediatric tools, training and educational programmes to support community pharmacists in managing child-related health matters.

Key points

- The role of community pharmacy (CP) has expanded over the past decade following the introduction of several advanced services, such as the new medicine service. Community pharmacists are experts in medicines use and very accessible, meaning they are well placed to provide information and advice to parents of children with minor ailments;

- Despite several initiatives that have promoted the extension of CP services, awareness regarding the services available for children and young people is still low. Additionally, some parents may lack confidence in the knowledge and ability of pharmacists to manage child-related health concerns;

- This review highlighted the limited evidence available on parents’ and young people’s views of CP and demonstrated that additional research is needed to elucidate the barriers impeding parents’ use of CP for their child’s health issue.

Introduction

Over the past decade, several health programmes and services have been introduced to support children and their families in the community. These include the Transforming Community Services programme, which focuses on supporting the integration of health systems and improving community services and quality of care, including those provided specifically for children and young people, and their families[1]. This includes health services provided by the community pharmacy (CP).

Given CPs’ central position in the network of health service providers within the local community, they are vital in providing effective public health interventions that go beyond their traditional role of dispensing medications[2]. CPs provide a wide range of commissioned (e.g. flu vaccination, chlamydia screening and treatment) and non-commissioned (e.g. medication dispensing, advice and signposting) services[3]. Community pharmacists are experts in medicine use and are accessible registered healthcare professionals with clinical knowledge; therefore, they are often people’s first point of contact and, for some, they are the only contact[3]. In the past few years, government-led initiatives in the UK, such as ‘Ask your Pharmacist’ and the ‘Stay Well Pharmacy’ campaigns, have emphasised extending CP services and building on the public’s understanding of these services. They have done this by increasing patient awareness about the various health issues CPs can assist with, such as dealing with minor illness without the need to visit a GP or hospital emergency department (ED)[4–7].

Several advanced services have been introduced to further strengthen CP’s role in public health and reduce the burden on other healthcare sectors. For example, the new medicine service (NMS) is a CP-commissioned service aimed to provide support and advice for selected long-term conditions (e.g. hypertension and asthma), to help improve patients’ adherence to their medicines[8]. A 2016 randomised controlled trial by Elliott et al. assessed the NMS versus current practice in 46 CPs in England that provided the NMS to patients with long-term conditions[9]. Elliott et al. concluded that patients welcomed the convenience of this NMS, and resulted in improved adherence of the patient to their medication[9]. However, studies have reported that the NMS is underused in children and remains a challenge for pharmacists to undertake, owing to the difficulties in obtaining consent from children, as well as the lack of clarity of guidance for paediatrics, as perceived by pharmacy staff[10,11]. Although around 20% of the questions on the General Pharmaceutical Council registration assessment for pharmacists are related to paediatrics[12], pharmacists don’t always receive in-depth teaching on paediatric medicines, nor are specific CP paediatric training courses widely available. All of these factors could contribute to the lack of confidence among community pharmacists in feeling competent in providing reviews of children’s medicines[10].

Since 2004, two schemes focusing on minor ailments (MA) management in CP have been launched in the UK to reduce demands on other stretched healthcare services, such as GPs and EDs. The ‘Pharmacy First’ scheme allows patients to receive advice from a community pharmacist on MA treatments without the need to visit their GP[13]. In 2019, the Community Pharmacist Consultation Service (CPCS) was introduced to further raise the profile of CP by consolidating the integration of CP services into the urgent care services of the NHS[14]. The CPCS plays a vital part within the urgent care system. Patients who call NHS 111 or their GP regarding a minor ailment are referred to a local CPCS where they can receive treatment closer to their homes[14]. However, workload issues in CP and the lack of CP’s service integration with other healthcare services, such as GPs and hospitals, have been seen as detrimental factors that deter parents and carers from fully using CP services[15].

As per the General Pharmaceutical Council standards, community pharmacists should provide patient-centred care that goes beyond the medication supply role that they and other pharmacy staff are expected to provide to people visiting CP[16]. Research has shown that community pharmacists can deliver patient-centred care interventions, including the provision of information and advice to parents of children with minor illnesses (e.g. eczema) that is tailored to meet their specific needs and concerns, and that such an intervention is highly valued by parents[16,17]. A 2012 Finnish study investigated the sources of information that parents of children aged under 12 years access regarding their child’s medication using a self-completed questionnaire, with the results showing that 44% of respondents (n=4,020) sought information from pharmacists[17]. A before-and-after intervention pilot study, conducted in England, assessed the effectiveness of community pharmacists in promoting best practice in applying emollient cream for eczema in children[18]. The study included 50 participants (children aged under 8 years and their parents) and reported that the intervention delivered by pharmacists resulted in a reduction of the symptoms of eczema (e.g. itching) and improved adherence to the medication[18].

As a result of the changes and improvements to CP services in recent years, this review aimed to provide an update on the available evidence on the views and experiences of parents, carers and young people using CP services for child-related health matters in the UK over the past ten years. Gathering patient views and experiences is considered a cornerstone of quality of care in any healthcare system, and can be used to inform future research and help healthcare providers make decisions on how best to improve or redesign services and enhance their delivery and governance[19,20].

Methods

Data sources, abstraction and synthesis

This review was conducted and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines for systematic reviews. A literature search was conducted using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases for studies published between January 2009 and December 2019. Several new initiatives (e.g. chlamydia screening[21] and medicine use review services[22]) were introduced in the UK in 2005, and this time period was selected to capture studies that have been conducted in the ten years following the introduction of those changes.

Search terms included combinations of synonyms and index terms related to children, parents/caregivers, experience and views; community pharmacy services and the UK (see box).

Box: MEDLINE and EMBASE search terms

Experience(s) OR perspective(s) OR awareness OR opinion(s) OR perception(s)

AND

Parent(s) OR carer(s) OR guardian(s) OR adolescent(s) OR young people OR children OR pre-school children OR preschool children OR teens OR teenager(s)

AND

Community pharmacy(ies) OR community pharmacist(s) OR local pharmacy(ies) OR chemist(s)

AND

Services OR pharmaceutical care OR community pharmacy services OR pharmacy services

AND

United Kingdom OR UK OR Great Britain OR England

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The scope of the review was limited to studies reporting original research on the experience and views of parents/carers and young people using CP services in the UK for children below the age of 18 years. Studies were limited to those reported in English, using the language filter on the databases. Searches were restricted to studies published between 1 January 2009 and 31 of December 2019 using the publication year filter. Only articles where the full texts were available were included in the review. Relevant studies were also identified from the reference lists of the included articles.

Studies describing CP services for young people aged above 18 years or for both adults and children, from which paediatric data could not be separated and analysed were excluded. Non-human studies, conference abstracts, letters, editorials and review articles were excluded. Non-UK based studies reporting on CP services for children were also excluded.

The databases were searched by one investigator (ANR) and a list of articles generated based on screening of the titles and abstracts. A full-text review was conducted independently by two reviewers (ANR, ST) using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreement was resolved by discussion. Data extracted included information related to the references, study aim, study design, sample size, study population and summary of the relevant findings.

Owing to the methodological heterogeneity of the articles, quality assessment of the included studies was not performed.

Data analysis

Given the small number of eligible studies and the heterogeneity of the results between them, a narrative synthesis of the findings was undertaken. This approach allows for an objective analysis of the existing evidence and the identification of knowledge gaps[23].

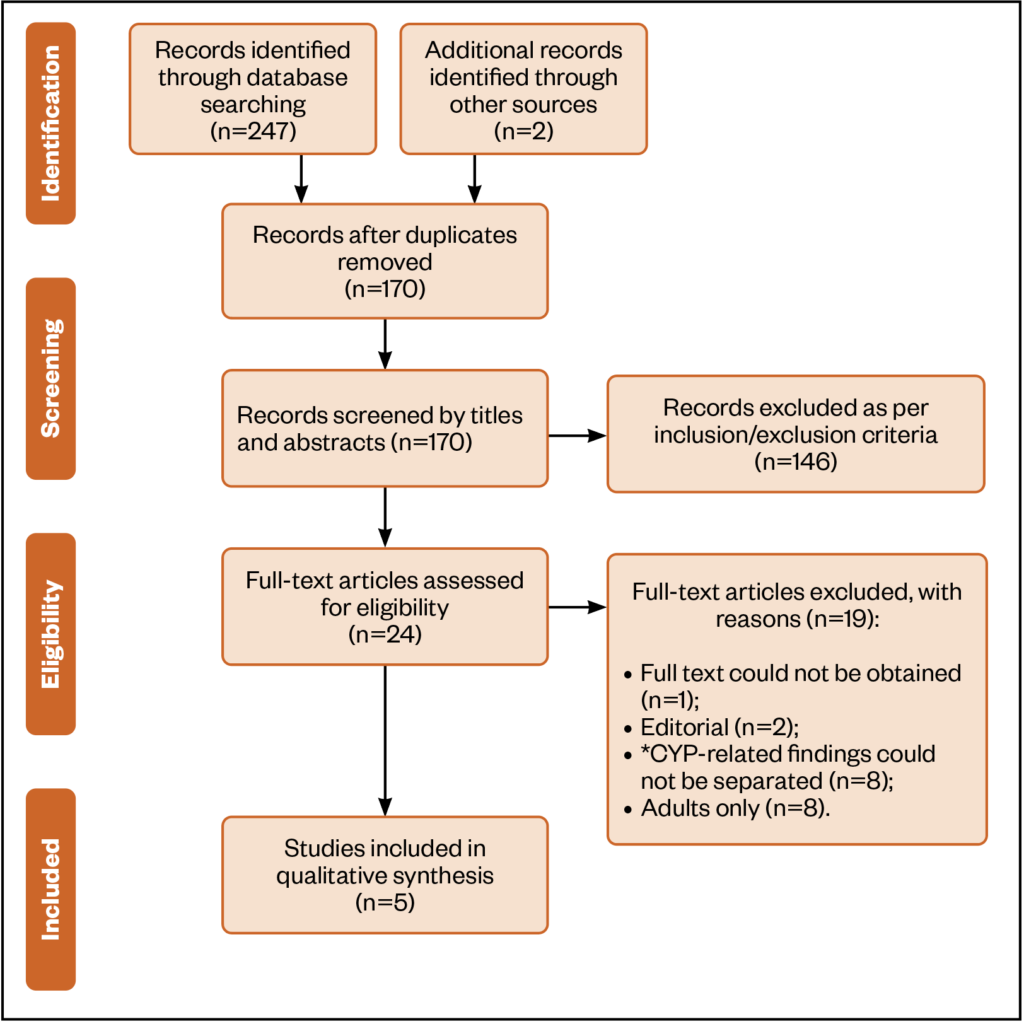

A total of 249 articles were identified using the search criteria, 170 remained following the removal of duplicates. Of these, 24 were potentially relevant and their full texts were assessed for eligibility. Only 5 articles were found to meet the inclusion criteria and were included in the review (see Figure). Four of the five studies were conducted in England, and one in Scotland, and details of all of the included studies are summarised in the table below.

*CYP = children and young people

Pharmacists as sources of information and advice

Two studies reported on parents/carers’ perception of pharmacists as sources of information for non-prescription medications[24,25]. Both were conducted by the same research team and the findings were reported from the same study cohort, in which they conducted a self-completed survey (n=134) supplemented with follow-up phone interviews (n=38) with parents and carers purchasing oral medications for their children (aged 0–4 years). Both studies reported that parents and carers valued the advice received (spoken and written [e.g. leaflets]) and believed it was helpful[24,25].

However, Gray et al’s study highlighted that there are still some issues surrounding parents’ trust in pharmacy services, with only 29% (n=32/109) preferring to receive information and advice from CP[25]. It was reported that carers would seek health information from the GP and internet over pharmacists’ advice.

Similar findings were reported by Boardman et al., where 37% of parents and carers (n=50/134) reported that the pharmacists gave them advice on non-prescription medicines purchased for their preschool children, whether they asked for it or not[24]. Out of those parents and carers who rated the advice (n=69), the majority (82%; n=57) stated that it was ‘very helpful/helpful’ and they fully understood.

These two studies suggest that parents’ perception of their need to ask or receive advice from pharmacists is related to their self-perception as experts or novices in children’s medication. However, a few parents stated that pharmacy staff should initiate the interaction with them and not just assume parents’ expertise with a child’s medicines[24,25].

However, given that both of the above studies were published by the same research team, reporting findings from the same study cohort, there is a risk of publication bias. In addition, the response rates were considered low (see Limitations).

Minor ailment management

Three studies reported on parents’ approach to children’s minor ailment management[26–28]. These studies highlighted that community pharmacists were not the first point of contact for parents to seek advice or information for child-related health issues.

In the first study, conducted by Neil et al., five focus groups and three individual interviews were conducted with parents (n=27) of children aged under five years[26]. The study investigated the resources parents accessed for information on managing minor illness at home. The study reported two main reasons parents gave when asked what prevented them from seeking information on a minor illness from their local pharmacy: lack of ability of the pharmacist to prescribe for children less than five years old, and the struggle to find a pharmacy that is open out-of-hours[26]. The majority of participants were mothers (89%; n=24) — there were only three fathers, meaning that fathers’ views and experiences were not representative. In addition, most of the participants with low educational attainment or no qualifications had low literacy, hence the impact of participants’ educational levels on the parents’ decision to seek information from their local pharmacies was not clear from the study findings.

A second study by Gidman and Cowley involved focus groups with 26 participants to explore their views and experience of CP services[27]. Around one-third of participants, particularly mothers with young children (31%; n=8), had a positive view about the pharmacists’ ability to provide them with minor-illnesses services. They believed that pharmacists’ knowledge about over-the-counter (OTC) medicines allow them to competently provide them with the service[27]. However, only a small number of parents were included in the study, hence the findings might not be generalisable.

The study by Muirhead et al. investigated the type of services that parents or carers would approach to treat their children’s oral pain[28]. The data was collected using a survey questionnaire completed by adolescents and parents/carers (n=6,915) who visited CPs to collect pain prescriptions or buy OTC pain medicines for children, of these 64% (n=4,425) had a child with any oral pain. The study showed that CP was not the first point of contact for most parents of children with oral pain; apart from dentists (30%; n=1,310), 28% (n=1,265) of parents had been to multiple health services, such as their GP and ED, before going to the CP. The study’s authors estimated that the NHS spends around £2.3m annually on children’s oral pain management because of the inappropriate use of multiple health services outside dentistry (e.g. GP, health visitor and practice nurse)[28]. However, although the study collected information from 51% of CPs in London (n=951), the cost was extrapolated without taking into account the variations in the number of parents during different seasons. For example, during the winter season, higher use of OTC oral pain medicines for children might occur to treat common cold symptoms, such as a sore throat.

Discussion

This review highlights that the paucity of awareness of parents or carers about CP services provided for children remains an issue, despite the efforts that have been made by several government-led initiatives, such as the ‘Stay Well Pharmacy’ and ‘Ask Your Pharmacist’ campaigns[4,5]. These findings are consistent with a previous study in the area of CP services for adults[29]. The lack of trust in pharmacist’s knowledge and ability in dealing with a child minor illness identified in this review has also been highlighted in a 2015 report published by the International Longevity Centre[30]. This report found that parents would seek health information from an online platform and GPs, in addition to the information they have been given by pharmacists[26]. However, it is worth noting that during the current COVID-19 pandemic, public perception of CP has improved, especially in relation to self-care. A recent online survey conducted by the National Pharmacy Association (NPA) found that 81% of respondents had a positive view of community pharmacists compared to 66% in 2016[31].

The guidelines for most of the schemes and initiatives to date were designed for the wider population and are not particularly focused on children and young people. In addition, community pharmacists are not always specifically trained in paediatric medicines, which may contribute to the low level of confidence. A 2018 UK study of 76 community pharmacists used a semi-structured survey to determine whether they performed medication reviews for children on long-term medications and identify the type of medication-related issues experienced by children and/or their parents. In the study, pharmacists (9.2%; n=7) stated that they are less confident in their ability in providing advice on a child-related matter owing to a lack of training[10]. The common reasons behind the community pharmacists’ belief that they are unable to undertake NMS with children and young people included the difficulties to obtain consent, that children are not always present when their medicine is collected by their parents or that children do not fall within the targeted medication groups[8,13].

Limitations

This review focused on providing an updated summary of the views and experiences of parents, carers and young people on their use of CP for child-related matters from studies published in the past ten years. Only a small number of studies were identified, which indicates the limited research that has been done in this area.

Studies focused on community pharmacists’ perspectives in providing services to children were not considered in this review, hence inference to parents’ and young people’s experiences may have been missed. Articles with no full text were excluded and grey literature were not considered, hence findings of studies that were not published in peer-reviewed journals or reports on public health interventions and evaluations, and charities reports related to paediatric services in CPs may have been missed. Furthermore, of the five papers included, two were from the same study[24,25]. This represents a potential risk of bias in the results as they were conducted by the same research team.

No studies examining young people’s opinions on their use of CP in the past ten years were found. Therefore, given the scarcity of evidence on parents and young people’s perceptions and views on CP services for children, there is a need for future work to tackle this evidence gap.

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that there is still limited evidence available on the perception from parents, carers and young people on the use of CP services for children, despite several initiatives promoting CP that have been introduced in the UK in the past ten years[4,5]. Despite a recent drive by the NHS for patients and the public to think ‘pharmacy first’ for minor ailments[13], it is evident that awareness of the CP services available for children, as well as parents trust in pharmacists’ capabilities in dealing with child-related matters, is an issue that needs to be addressed in future research. Several factors might contribute to the low awareness, such as workload issues in CP and the lack of CP’s service integration with other healthcare services. These issues need to be addressed in future research in order to improve awareness of CP.

The following recommendations are needed to further understand and promote the use of CP for child-related health matters:

- More research is required to explore how community pharmacists can be supported in gaining the skills and confidence needed to engage, interact with and contribute effectively to improve the health of children and young people. However, multidisciplinary research involving all parties (e.g. pharmacy staff, service commissioners and other stakeholders, such as the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education) is needed to devise, develop and implement the best evidence-based solutions to support community pharmacy staff in dealing with children and young people’s health-related issues;

- More promotion and reinforcement by other healthcare professionals, services and local authorities, such as GPs, clinical commissioning groups, and nationally by Public Health England, Wales and Scotland, to raise awareness about the CP services available for children and young people is essential to encourage them and their parents to visit CP before seeking help elsewhere. This would not only raise the profile of CP in the public’s view regarding children’s services but will also help relieve the pressure on other services, such as GPs and EDs.

Financial disclosure and conflict of interest statement

Asia N Rashed received funding from the Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacist Group to conduct paediatric research. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

- 1Department of Health . Transforming community services: ambition, action, achievement. Transforming services for children, young people and their families. Department of Health. 2009.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215783/dh_124198.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 2Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. The contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health: summary of report of the literature review 1990-2007. Semantic Scholar. 2009.https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/32d9/8410062470bfab07247ef689e2f479670331.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 3Public Health England. Pharmacy: A way forward for public health. Public Health England. 2017.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/643520/Pharmacy_a_way_forward_for_public_health.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 4National Pharmacy Association. Ask Your Pharmacist Campaign. National Pharmacy Association. 2019.https://www.npa.co.uk/ayp2019 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 5NHS England. Stay Well Pharmacy Campaign. NHS England. 2019.https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/stay-well-pharmacy-campaign (accessed Jul 2021).

- 6NHS England. NHS Five-Year Forward View. NHS England. 2014.https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 7Pharmacy Research UK. Community Pharmacy Management of Minor Illness-MINA study. Final report. Pharmacy Research UK. 2014.https://pharmacyresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/MINA-Study-Final-Report.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 8Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. New Medicine Service. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. http://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/nms/ (accessed Jul 2021).

- 9Elliott RA, Boyd MJ, Salema N-E, et al. Supporting adherence for people starting a new medication for a long-term condition through community pharmacies: a pragmatic randomised controlled trial of the New Medicine Service. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;25:747–58. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004400

- 10Aston J, Wilson KA, Terry DRP. Children/young people taking long-term medication: a survey of community pharmacists’ experiences in England. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2017;26:104–10. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12371

- 11Alsairafi Z, Mason J, Davies N, et al. Community pharmacy advanced adherence services for children and young people with long-term conditions: A cross-sectional survey study. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2020;18:1720. doi:10.18549/pharmpract.2020.1.1720

- 12General Pharmaceutical Council. Registration assessment framework. General Pharmaceutical Council. https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/53-registration-assessment-framework (accessed Jul 2021).

- 13Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. . Pharmacy First. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. . https://psnc.org.uk/city-and-hackney-lpc/home/local-services-list/255-2/ (accessed Jul 2021).

- 14NHS England. NHS Community Pharmacist Consultation Service (CPCS) – integrating pharmacy into urgent care. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/primary-care/pharmacy/community-pharmacist-consultation-service/ (accessed Jul 2021).

- 15Hindi AMK, Schafheutle EI, Jacobs S. Community pharmacy integration within the primary care pathway for people with long-term conditions: a focus group study of patients’, pharmacists’ and GPs’ experiences and expectations. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20. doi:10.1186/s12875-019-0912-0

- 16General Pharmaceutical Council. Standards for pharmacy professionals. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2017.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf (accessed Jul 2021).

- 17Holappa M, Ahonen R, Vainio K, et al. Information sources used by parents to learn about medications they are giving their children. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2012;8:579–84. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.01.003

- 18Carr A, Patel R, Jones M, et al. A pilot study of a community pharmacist intervention to promote the effective use of emollients in childhood eczema. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2009.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/research/a-pilot-study-of-a-community-pharmacist-intervention-to-promote-the-effective-use-of-emollients-in-childhood-eczema (accessed Jul 2021).

- 19Crawford MJ. Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ 2002;325:1263–1263. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7375.1263

- 20Bate P, Robert G. Experience-based design: from redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2006;15:307–10. doi:10.1136/qshc.2005.016527

- 21Public Health England. Chlamydia screening in general practice and community pharmacies. Public Health England. 2014.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/chlamydia-screening-in-general-practice-and-community-pharmacies (accessed Jul 2021).

- 22Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Medicines Use Review (MUR) – Archive information. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. 2021.https://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/advanced-services/murs/ (accessed Jul 2021).

- 23Rodgers M, Sowden A, Petticrew M, et al. Testing Methodological Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. Evaluation 2009;15:49–73. doi:10.1177/1356389008097871

- 24Boardman HF, Gray NJ, Symonds BS. Interactions between parents/carers of pre-school children and pharmacy staff when buying non-prescription medicines. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:832–41. doi:10.1007/s11096-011-9546-6

- 25Gray NJ, Boardman HF, Symonds BS. Information sources used by parents buying non-prescription medicines in pharmacies for preschool children. Int J Clin Pharm 2011;33:842–8. doi:10.1007/s11096-011-9547-5

- 26Neill SJ, Jones CHD, Lakhanpaul M, et al. Parent’s information seeking in acute childhood illness: what helps and what hinders decision making? Health Expect 2014;18:3044–56. doi:10.1111/hex.12289

- 27Gidman W, Cowley J. A qualitative exploration of opinions on the community pharmacists’ role amongst the general public in Scotland. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2012;21:288–96. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12008

- 28Muirhead VE, Quayyum Z, Markey D, et al. Children’s toothache is becoming everybody’s business: where do parents go when their children have oral pain in London, England? A cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open 2018;8:e020771. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020771

- 29Janet K, Charles W M. Views of the general public on the role of pharmacy in public health. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research. 2010.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1211/jphsr.01.01.0013 (accessed Jul 2021).

- 30Bamford S, Kneale D, Wilson J, et al. A New Journey to Health—Health Information Seeking Behaviour Across the Ages. London: : International Longevity Centre 2015.

- 31Community pharmacies were ‘essential’ during COVID-19 pandemic, public says. The Pharmaceutical Journal Published Online First: 2020. doi:10.1211/pj.2020.20208163