Introduction

The community pharmacy contractual framework, introduced in April 2005, was designed to provide the foundation structure to support the modernisation of community pharmacy and pharmaceutical services.[1]

Pharmacy contracts also moved to being held locally by primary care organisations. PCOs thus became responsible for monitoring community pharmacies against the contract and for commissioning local pharmaceutical services under its enhanced services tier.

The 2008 White Paper “Pharmacy in England — building on strengths, delivering the future” sets out a national vision for pharmacy.[2]

It is clear that in order to be well placed to deliver these developments, community pharmacies need to be meeting the contract’s essential services requirements as a minimum.

The purpose of our project was to evaluate the support offered by one Yorkshire primary care trust to its local community pharmacies, focusing on communication and core contract essential services requirements.

Communication between PCOs and pharmacies is vital. The main methods of communication in use in the PCT involved in this study included a newsletter, quarterly pharmacy forum evening meetings and contract assurance monitoring annual self assessments with periodic visits. The newsletter is published by the PCT every two months and covers current news, including practical issues relating to the community pharmacy contract.

The forum meetings are designed to encourage discussion about how best to tackle pharmacy contract challenges, service developments and to obtain opinions and feedback from the attendees. A formal overall evaluation of communication between the PCT and pharmacies had not previously been undertaken.

Repeat dispensing can be convenient for patients and improve their access to medicines. The Pharmacy Practice Research Trust reported in 2007 that repeat dispensing only accounted for around 1 per cent of total prescriptions dispensed.[3]

Primary Care Contracting (PCC) has nationally identified a number of barriers to the development of a repeat dispensing service; they include lack of start-up resource, patients and GPs not fully understanding the benefits of the service, reluctance to change practice, variations in staff competence and competing priorities.[4]

These barriers have also been echoed by a number of other publications.[2],[5],[6]

The Community Pharmacy Patient Questionnaire (CPPQ) is part of the clinical governance requirements of the contractual framework.[1] Each community pharmacy is required to undertake a CPPQ annually, with the minimum sample size determined according to dispensing volume. Pharmacies are required to share key CPPQ findings with their local PCO.[1]

Currently there is little published work relating to the CPPQ and we hope our study will help to further understanding of this topic.

Every year pharmacies are required to complete a minimum of two clinical audits as part of the clinical governance essential service,[1]

with the aim of continually improving their services — one multidisciplinary audit (topic determined by the PCO) and one practice-specific audit (topic determined by the individual pharmacy). The Pharmacy Practice Research Trust in 2007 found that only 67 per cent of contractors completed the practice-specific audit and 55 per cent the PCO-determined multidisciplinary audit.[3] Audit was also one of the three most commonly cited training needs in an evaluation of the community pharmacy contract in 2007.[3]

Our study aims to explore PCO roles in pharmacy clinical audit by obtaining opinions from pharmacists.

Pharmacist and pharmacy support staff skill development is an important part of clinical governance. Which? magazine recently reported poor advice being given in one-third of pharmacies tested, indicating staff training gaps.[7]

Research was recently conducted by Schafheutle et al about pharmacy support staff in community pharmacy. The study identified that pharmacy support staff aged under 40 years had a greater interest in further training and career progression than older staff. Poor salaries were also identified as potential barrier to further training.[8]

As the roles of and services provided by pharmacies are evolving, the need for further training and development is increasing, so we have explored opinions regarding this in our study.

Public health campaigns are also part of the essential services in the community pharmacy contract, with each pharmacy expected to participate in up to six PCT-identified campaigns annually.[1] It is the role of the PCO to determine the topics of the campaigns and to provide appropriate resources (eg, patient literature) to support them.[1]

We hope our study will help to clarify how PCOs can further support the implementation of such campaigns.

In April 2009, the Department of Health published the document “World class commissioning [WCC]: primary care and community services — improving pharmaceutical services”.[9]

Following on from the 2008 White Paper,[2]

this document identifies how PCOs can and should apply the WCC competencies to the commissioning of pharmaceutical services. This is resulting in further changes to how pharmaceutical services are commissioned and the roles of PCOs within this.

The overall aim of our research was to determine how the PCT studied could better support its local community pharmacies in delivering the contract’s essential services, within the context of pharmacy WCC. It was also developed to help address the improvements in pharmacy service commissioning called for in the White Paper and pharmacy WCC documents.[2],[9]

We hope that our study will help to address some of the existing gaps in the published literature on this topic and we offer some advice to other PCOs accordingly.

Method

Our study comprised a structured postal questionnaire, with a mixture of closed and open questions in seven subsections – communication, repeat dispensing, CPPQ, clinical audit, staff training, public health campaigns and demographic information. The questionnaire was developed in conjunction with the PCT and with input from the local pharmaceutical committee. The draft questionnaire was then sent to 11 community pharmacists outside the area as a pilot, following which a number of minor amendments were made to the questionnaire structure and wording. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of Bradford Ethics Committee.

The study population was all 111 community pharmacies in one Yorkshire PCT. Prior approval was sought via letter from superintendent pharmacists of all multiple pharmacies with branches in the area. The questionnaire was sent to all 86 consenting pharmacies in February/March 2009, with one reminder sent to non-responders after four weeks. It was sent with an explanatory covering letter and a coded postcard. Questionnaires were anonymous; pharmacies were asked to return the coded postcards separately from the questionnaire, enabling non-responders to be identified and followed up. Any pharmacies not responding eight weeks after the initial mailing were classed as non-responders.

Data from the closed questions were inputted into a SPSS database. Descriptive statistics were used to determine frequencies of responses. Chi-squared tests were used to determine any significant correlations; Fisher’s Exact tests were used where numbers were too small to use chi-squared. Data from the open questions was entered into a Microsoft Excel database; responses were then categorised and tabulated where appropriate.

Results

A response rate of 43.0 per cent (37/86) was achieved. Of the pharmacies responding 16 (43.2 per cent) are situated in an urban area, 15 (40.5 per cent) suburban, four (10.8 per cent) rural, and two (5.4 per cent) undisclosed. The responses reflected the pharmacy demographics of the area (65 per cent multiples and 35 per cent independents).

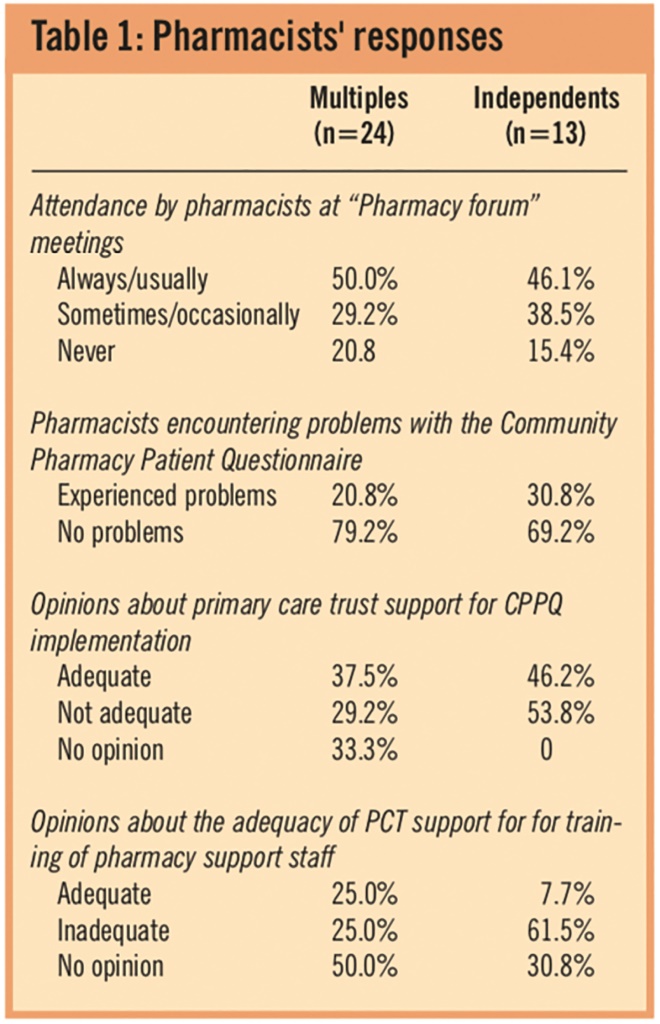

The PCT pharmacy newsletter was perceived as an effective method of communication by 29 respondents (78.4 per cent). Table 1 shows attendance at the regular PCT-run evening “Pharmacy forum” meetings. Attendance by pharmacists working in multiple and independent pharmacies is not significantly different (P=0.953, Fisher’s Exact test). These meetings were deemed to be relevant by seven of eight pharmacy owners (87.5 per cent), 17 of 22 pharmacy managers (77.3 per cent), three of three employed pharmacists (100 per cent) and two of four locum pharmacists (50 per cent). Suggestions to improve PCT communication with community pharmacies included the “use of electronic communication” (nine respondents) and “direct contact with a dedicated PCT pharmacist for queries and help with new initiatives” (four respondents). Another suggestion was that “pharmacists should be able to gain access to the NHS intranet” (two respondents) to enhance communication between groups.

Table 1: Pharmacists’ responses

Dispensing staff were reported to be appropriately trained in repeat dispensing by 78.4 per cent of the 37 respondents. Of the multiples responding 75.0 per cent reported that staff were adequately trained as opposed to 85.0 per cent of independents, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.182, Fisher’s Exact test). Overall, 36.1 per cent of respondents believed they were adequately supported by the PCT in the repeat dispensing service; an equal proportion thought they were not adequately supported and 27.8 per cent had no opinion. Problems with repeat dispensing were reported by 54.1 per cent of pharmacists — 58.3 per cent of multiples and 46.2 per cent of independents (P=0.478, chi-squared test). The main problems reported were “low uptake from GP surgeries” (18 respondents) and “low patient awareness” (three respondents).

Problems with implementing the CPPQ were reported by 24.3 per cent of respondents. Table 1 shows the percentage of pharmacies encountering problems by pharmacy type; these differences were not statistically significant (P=0.501, chi-squared test). Table 1 also shows the opinions on PCT support for implementation of the CPPQ. Overall, this was not thought to be adequate by 37.8 per cent of pharmacies — 29.2 per cent of multiples and 53.8 per cent of independents; this difference was significant (P=0.047, chi-squared test). The most commonly reported problems were the design and process of the CPPQ (four respondents), the “reluctance of patients to complete the questionnaires” (three respondents) and the fact that the CPPQ is “time consuming” (three respondents). Suggested improvements included “shorter questionnaires” (two respondents) and a “lower target response rate” (four respondents).

The most common recent pharmacy-specific audit topics included:

- Prescription interventions (16 respondents)

- Warfarin and clopidogrel prescribing (six respondents)

- Waiting times (four respondents).

Improvements suggested in PCT support for clinical audit in community pharmacy included the following:

- Improve clinical audit design and process (seven respondents)

- PCT/pharmacists to suggest clinical audit topics (five respondents)

- Topic relevant to community pharmacy (three respondents)

- Better support/direct contact/helpline (four respondents)

- Staff training (three respondents)

- Administration and monetary support (three respondents)

- Receive feedback on outcomes (two respondents)

- More notice before audit (two respondents)

A wide variety of suggestions was made with regards to future topics for multidisciplinary clinical audits. The most popular suggestions included “returned medicines” (three respondents), “prescribing for asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients against National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guidelines” (three respondents), and “patient brand requirements” (two respondents).

Staff training was perceived to be supported adequately by the PCT by only 18.9 per cent of pharmacies; 37.8 per cent did not feel adequately supported and 43.2 per cent had no opinion. Table 1 shows a breakdown of the perceived PCT support for training of pharmacy support staff by pharmacy type. PCT support was not felt to be adequate by 25.0 per cent of multiples and 61.5 per cent of independents, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.136, Fisher’s Exact test). A number of suggestions were given regarding ways in which the PCT could improve support for training of pharmacy support staff. Key themes were as follows:

- Timing of training (10 respondents) — eg, repeat sessions, flexible dates, evening training

- Type of training (10 respondents) — eg, online training packs, in-pharmacy training

- PCT interface (five respondents) — eg, dedicated PCT pharmacist for support and contact, newsletters for support staff

- Who the training is for or aimed at (four respondents) — eg, independent pharmacies, counter staff, technicians, locums

The questionnaire responses showed that 67.6 per cent of respondents felt supported by the PCT for public health campaigns; 77 per cent of independents and 63 per cent of multiples (P=0.642, Fisher’s Exact test). Only 8.1 per cent of respondents did not feel supported by the PCT for public health campaigns and 24.3 per cent had no opinion. A number of comments, both positive and negative, were made regarding the perceived support from the PCT for public health campaigns. The main problem identified was “targeting and engaging with the public” (four respondents). Suggestions for improvement included “more and varied types of publicity material” (two respondents), and “more instructions on how to carry out the campaign” (two respondents). Most respondents (67.6 per cent) thought campaign topics were relevant to their local population; only 5.4 per cent though campaigns were not relevant and 27 per cent had no opinion.Analysis by pharmacy location and type did not reveal any significant differences in these opinions (Fisher’s Exact test).

Discussion

The response rate of 43 per cent was in keeping with average response rates for postal questionnaires. There were difficulties in obtaining superintendent pharmacist approval for the questionnaires to be sent to some multiple pharmacies, including one who refused to participate. The proportion of responses reflected the local split of multiple versus independent pharmacies and it is thus hoped that they are reasonably representative of the area studied.

Communication between the PCT and community pharmacies was generally perceived positively. Four-fifths of respondents agreed that a regular written newsletter is an effective method of communication; quarterly evening “Pharmacy Forum” meetings were also well received. Responses demonstrated that pharmacists value some face-to-face communication in addition to written methods. Communication could be further improved by making better use of electronic media, particularly the PCT website and some PCOs have already successfully done this.[10]

Half of pharmacies reported encountering problems with the repeat dispensing contractual service and a fifth of pharmacies reported not having appropriately trained dispensers to deliver repeat dispensing. Although not statistically significant, more difficulties with repeat dispensing appeared to be encountered by multiple pharmacies than independents. It is possible that this is partly due to a higher turnover of staff, although further work would be needed to confirm this. The main barriers perceived included low uptake of the service by GPs, issues around pharmacy-GP communication and lack of awareness of the service by patients. These findings are consistent with other studies[4],

[5],[6]

and are highlighted in the White Paper.[2]

There were calls for the PCT to further support the implementation of repeat dispensing by facilitating increased collaboration between GPs and community pharmacists and promoting the service to healthcare professionals and the public. There is also an opportunity to learn from other PCOs’ successes in implementing repeat dispensing.[2]

,[5]

Moreover, the recommendation to facilitate increased collaboration between GPs and community pharmacists is in line with pharmacy world class commissioning,[9]

particularly in relation to competencies 4, 8 and 10,9 and applies more widely than just to repeat dispensing; this should be a key priority for PCOs.

A quarter of respondents reported problems with the CPPQ, and two-fifths would like more PCO support with this — independents significantly more so than multiple pharmacies. There appears to be some confusion among community pharmacists around the CPPQ and the role of the PCT in relation to it. Some respondents requested the PCT to amend the questions or reduce target numbers — both of which are national contractual requirements as opposed to PCO-determined aspects. Issues that the PCO could support include: promoting pharmacies to share ideas with each other on how to improve CPPQ response rates and raising awareness of the CPPQ with the public. The latter is in line with a recommendation made by the Pharmacy Practice Research Trust in 2007.[3]

The importance of raising awareness of pharmacy with the public is also highlighted in the White Paper[2]

and as part of pharmacy WCC, particularly in relation to competency 3.9 The role of PCOs within this is key.

There also remains some confusion around clinical audit — in particular the difference between the contractually specified practice-based audit and the PCO-determined multidisciplinary audit. For example, a number of pharmacies gave the topic of the most recent PCT multidisciplinary audit (prescription interventions) as their response to the question asking about their practice-based audit topic. Notwithstanding this, there was a diverse range of topics undertaken for practice-based audits, with anti-coagulants and waiting times being among the most popular. Some interesting ideas were put forward for the topic of the next multi-disciplinary audit and these were fed into the PCT process for determining audit topics. From the responses received in relation to audit, it appears that some pharmacies expect more from the PCT than is appropriate for it to provide as a commissioning organisation (eg, staff training, helpline, monetary support). Interestingly the PCT involved in this study had developed and disseminated a local audit support pack in addition to the national Royal Pharmaceutical Society audit templates (available via www.rpsgb.org) but some of the pharmacists responding to the questionnaire did not appear to be aware of these resources. It is noteworthy that this finding appears to contradict the largely positive views on communication between the PCT and pharmacies. Awareness-raising of existing national and local resources to support audit may help to further improve engagement with and quality of clinical audit in community pharmacy.

Almost two-fifths of respondents thought that the PCT did not provide adequate support for pharmacy staff training and development; more than half of independents but only a quarter of multiples. This discrepancy is likely to be due to multiple pharmacies receiving in-house staff training and support, whereas independents are more likely to need to seek external training support. Although the role of PCOs as commissioners — in relation to staff training and development — is now limited, PCOs have a role in signposting pharmacies and their staff to other existing sources of training and development opportunities, for example, through the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education, the National Pharmacy Association, local pharmaceutical committees and independent companies. There were calls for the provision of flexible, face-to-face training (offering options of daytime and evening sessions, and where possible in-pharmacy training) and more provision of alternative formats such as distance learning and online training. Organisations and institutions offering training and CPD support to pharmacists, technicians and pharmacy support staff may wish to consider this as part of their development plans.

PCT support for public health campaigns was perceived as good, with only three and two respondents, respectively, disagreeing with the views that support is adequate and that the campaign topics are relevant to the local population. From the comments it appears that pharmacies particularly value relevant information that is sent out in good time before each campaign. Suggestions for further improvement included: use of more novel resources (in addition to posters and leaflets), tailoring messages to different communities (eg, different socio-economic areas, use of community languages) and synchronising public health campaigns across different healthcare professions. Although some pharmacists liked the many and varied topics and linkage to national campaigns others believed more effort should be made to determine the needs of the target population in their local areas. This may well reflect the high diversity of the local population in this PCT. These findings echo those of an evaluation of pharmacy public health campaigns in Leicester, which has a similar diverse population to the PCT in this study.[11]

The findings also fit with current national strategy in using social marketing techniques to influence health-related behaviour.[12]

A good example of this is the targeting of public health campaigns to particular populations.

The local LPC was closely involved in this project, from the stage of questionnaire design right through to sharing of the findings. This was invaluable, both in facilitating the smooth running of the project and in disseminating and acting upon the findings. Importantly, it also enabled further consolidation of the PCT-LPC relationship.

It would be interesting to perform a similar study in other PCOs to determine whether our findings are representative of community pharmacists’ opinions nationally. It is also possible that some of the trends towards differences seen would have reached statistical significance if the sample size were larger. Additionally, some of the issues identified may be worth further exploration, for example, via interviews or focus groups, to elicit more detail than is possible via a postal questionnaire alone.

Finally repeating this study in the future, following implementation of some of the recommendations, would enable the effectiveness of the interventions to be determined. Repetition of this exercise could also help the PCO to examine its progress against some of the pharmacy WCC competencies.[9]

Conclusion

Although some of the findings are specific to the area in which the study was conducted, it is likely that others will be more widely representative. There were some important differences noted between multiple and independent pharmacies, not all of which were expected. To recognise these differences in the context of provider development, PCOs may wish to consider more explicitly recognising, and where appropriate addressing, the different needs of multiple and independent pharmacies. It appears that some independent pharmacies look to the PCO to provide the kind of support that is provided by “head office” functions in multiple pharmacies (eg, staff training, clinical audit, CPPQ support). The apparent confusion regarding the role of PCOs in relation to nationally negotiated services included in the core contract (notably CPPQ and clinical audit) highlights gaps in the understanding of some pharmacies about the deliverables included in the essential services part of the contract. This needs to be addressed by PCOs working towards pharmacy WCC competencies, particularly competencies 8 and 10.9 The importance of fostering good working relationships between community pharmacists and other healthcare professionals (most notably with GPs for repeat dispensing) was underlined and PCOs should prioritise this. Our study also further highlights the importance of raising awareness of community pharmacy with patients and the public — particularly around repeat dispensing, the CPPQ and public health campaigns.

The relationship of PCOs with independent contractors, including community pharmacies, is evolving in line with the development of world class commissioning.[9]

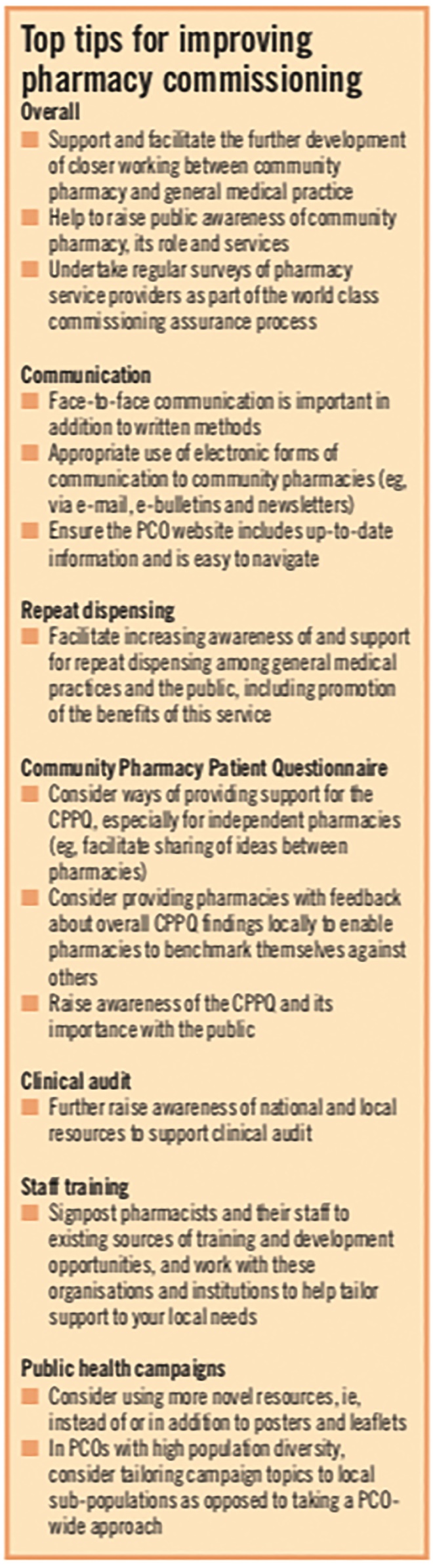

We hope that the key findings from our study prove helpful to other PCOs when planning and reviewing their approaches to community pharmacy commissioning. In particular the tool of surveying community pharmacy contractors, with LPC involvement and support, and using the findings to inform PCO planning in relation to provider development has proved useful. We recommend that all PCOs consider conducting a similar survey of community pharmacy providers, perhaps on an annual basis, as part of the WCC assurance process and to that end we have provided some tips to improve community pharmacy commissioning (see Panel below).

Panel: Top tips for improving pharmacy commissioning

Acknowledgements

We thank the other members of the project team (Rasheda Khatun, Ashraf Manjothi, Sheryar Noor and Shamas Ul Haq), the pharmacists who participated in the study and Bradford LPC

About the authors

Julie D. Morgan, PhD, MRPharmS, is lecturer in pharmacy practice at the University of Bradford.

Kelvin W. Y. Cheung and Fiona C. Thorp were undergraduate pharmacy students at Bradford University at the time of writing.

Correspondence to: Dr Morgan at Division of Pharmacy Practice, School of Pharmacy, University of Bradford, Richmond Road, Bradford BD7 1DP (e-mail j.d.morgan1@bradford.ac.uk)

References

[1] Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework. 2005. Available from: www.psnc.org.uk (accessed 20 July 2009).

[2] Department of Health . Pharmacy in England: building on strengths — delivering the future. London: DoH; 2008.

[3] Pharmacy Practice Research Trust. National evaluation of the new community pharmacy contract. 2007. Available at: www.pprt.org.uk (accessed 5 August 2009).

[4] Primary Care Contracting. Summary of feedback from MUR/repeat dispensing workshops. 2008. Available at: from www.lpc-online.org.uk (accessed 5 August 2009).

[5] National Prescribing Centre. Dispensing with repeats: a practical guide to repeat dispensing. 2008. Available at: www.npci.org.uk (accessed 5 August 2009).

[6] Elvey R, Ashcroft D, Noyce P. General practitioner engagement: the key to repeat dispensing? International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2008;16:303–8.

[7] Pharmacies get test of own medicine. Which? September 2008. Available at: www.which.co.uk/news/2008/09/ pharmacies-get-test-of-own-medicine-1573302008 (accessed 6 May 2010).

[8] Schafheutle EI, Samuels T, Hassell K. Support staff in community pharmacy: who are they and what do they want?International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2008;16:57–63.

[9] Department of Health. World class commissioning: primary care and community services — improving pharmaceutical services. London: DoH, 2009.

[10] Connelly D. PCTs’ experiences of monitoring. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;276:386.

[11] Nicholson S, Allen D. Pharmacy public health campaigns 2008/9. Directorate of Public Health & Health Improvement, Leicester City Primary Care Trust. 2008. Available at: www.phleicester.org.uk (accessed 18 August 2009).

[12] Department of Health. Ambitions for health: a strategic framework for maximising the potential of social marketing and health-related behaviour. London: DoH, 2008.