Abstract

Aim

To assess whether the safety of epidural analgesia had been increased two years after the introduction of measures to reduce the risks associated with the technique.

Method

Structured face-to-face interviews.

Subjects and setting

30 practitioners who are frequent users of the technique at University Hospital Lewisham in London.

Outcome measures

Respondents’ perceptions.

Results

67% thought the changes contributed to patient safety by making the epidural analgesia “much safer”, 27% thought it made it “safer” and 7% thought it made no difference. None thought the changes made the technique less safe. Human errors (32%) and labelling (18%) were thought to be the commonest sources of error.

Conclusion

The strategies introduced to minimise the risks associated with epidural analgesia were thought to contribute to patient safety by most practitioners who regularly use the technique.

One of the targets set in “Building a safer NHS for patients”1 was a reduction in serious drug errors of 40 per cent by 2005. Both this document and the earlier publication, “Organisation with a memory”,2 recognised that medication errors were a significant source of morbidity and mortality. Both reports advocated that action should be taken to reduce the incidence of medication errors, a position further reinforced in “A spoonful of sugar”.3

At University Hospital Lewisham, staff in the anaesthesia, nursing and pharmacy departments identified epidural analgesia as a high risk area for medication errors, particularly preparation, prescribing and administration errors. The administration of a local anaesthetic, on its own or more commonly with an opiate analgesic, by bolus injection or continuous infusion is an effective way to provide analgesia.4 The use of this technique has increased over the past 10 years and it is now commonly used, particularly in surgery and obstetrics.

Epidural analgesia has a significantly lower incidence of side effects,4 particularly sedation and respiratory depression, than do intravenous opiates alone. Although the technique is generally safe when used correctly, there are potential risks associated with it, particularly if errors are made in preparation, administration, prescribing or selection. In addition, infusion bags may be confused with bags of more commonly used crystalloid solutions and infused intravenously in error, with potentially fatal results.5

Before the introduction of new safety measures at University Hospital Lewisham, a wide range of strengths, volumes and drugs were available from the hospital formulary to be prescribed for epidural use. Final solutions were prepared in operating theatres and wards by medical and nursing staff. Moreover available products were used for a number of indications and were stored in the same medicine cupboards as the usual ward and theatre stocks.

Anaesthetics staff in particular believed there to be considerable risk in their preparation of the products for epidural analgesia and approached the pharmacy to prepare them. A risk assessment showed that pharmacy preparation would only address one set of risks, those associated with preparation. These risks would be reduced by transferring them to a controlled environment. However, this left a significant number of risks unaddressed and created new risks. In addition it would dramatically increase workload in the aseptic unit and no additional resources were available. Also, this increase in workload would be variable and unpredictable and require 24-hour, seven-day-a-week cover.

Following review by a group of senior pharmacists, consultant anaesthetists and senior nurses from the pain team, a range of changes to the service were introduced in autumn 2001. These changes aimed to cover all stages of the process and ranged from introducing constraints in the product range available to the introduction of dedicated pumps and new documentation to support prescribers. A summary of these changes is given in Panel 1.

Panel 1: Changes to epidural analgesia practice introduced in 2001

Reducing complexity

- Standardising epidural regimens

- Introducing ready made bupivacaine bags (purchased from licensed specials manufacturer)

- Introducing ready made bupivacaine and fentanyl bags (purchased from licensed specials manufacturer)

- Introducing ready made bupivacaine and fentanyl syringes (purchased from licensed specials manufacturer)

Introducing constraints

- Providing only a single strength of bupivacaine bags

- Providing a single strength of bupivacaine and fentanyl bags

- Limiting volumes to 50ml syringes and 250ml and 500ml bags

- Restricting use of 250ml bags to maternity department

- Never supplying 500ml bags to maternity department

Standardising documentation

- Providing dedicated, preprinted prescription sheets with clinical monitoring guidance

- Standardising system of ordering from the pharmacy

Providing epidural pumps

- Providing pumps dedicated for epidural infusion use only

- Providing distinctive connection lines for pumps

Labelling and storage

- Attaching bright, clear labels marked “For epidural use only” to bags before they are issued from the pharmacy

These wide-sweeping changes were introduced over a short period and were thought by senior staff to have addressed many of the risks associated with epidural analgesia. However, apart from a reduction in clinical incident reports, there was no evidence to support their effectiveness. Although the reduction in clinical incident reports was encouraging, clinical incident reporting is imprecise as a tool for measuring outcomes, and there is considerable under-reporting. This study was therefore set up to assess the impact of the changes two years after they had been introduced.

Method

The study was conducted over a three-week period at University Hospital Lewisham, a busy, inner-city hospital. Epidural analgesia is routinely used in eight clinical areas in the hospital. Frequent users of the technique were first identified. These included anaesthetists, operating department assistants (ODAs), and nurses working in recovery, in the surgical high dependency unit and on the pain team. Included was any practitioner who prescribed, prepared or administered epidural analgesia. Because the study was to determine the effect of the change, any practitioners who had not been working at the hospital before the changes in 2001 were excluded.

A list of 37 anaesthetists, nurses and ODAs who fulfilled the inclusion criteria was obtained from senior staff. A letter of invitation to participate in the study was sent to each of them explaining the purpose of the study, accompanied by an information sheet that included arrangements for confidentiality. Subsequently, potential respondents were contacted by bleep or telephone and invited to participate. An interview was arranged at a mutually convenient time and location. Tacit consent was implied by agreement to participate in the interview; however subjects were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. Thirty individuals agreed to participate in the study.

A structured face-to-face interview technique was used. It consisted of a series of scripted questions that addressed the various aspects of the service and the changes introduced. This series was constructed following discussions with the academic and practice supervisors, as well as the senior nurse for the pain team (who was not a participant). A selection of open and closed questions was used, and a Likert scale was used in some to obtain some differentiation. The questions were designed to cover a number of themes:

- Factors thought to improve patient safety in epidural practice

- Sources of error during prescribing, administration and preparation of epidural analgesics

- The overall impact of the changes introduced on patient safety

- Suggestions on how to improve the current service

- Demographic information

The interview was piloted on five hospitalpharmacists so as not to reduce the relatively small pool of potential subjects. Some minor amendments were made to the schedule.

All interviews were administered by a single researcher (IO) in a setting familiar to the subject, and the interview format was standardised as far as possible to avoid bias and ambiguity. Each interview lasted 10 to 15 minutes. The data were anonymised before entry onto an Excel spreadsheet for analysis.

The study was approved by the Lewisham Local Research Ethics Committee.

Results

Of the 37 potential participants who were approached, seven declined to take part. Of the remaining 30, 11 (37 per cent) were consultant anaesthetists, seven (23 per cent) were operating department assistants and 12 (40 per cent) were nurses). Of the 12 nurses, 6 were from the recovery room, four were from the surgical high dependence unit and 2 were from the pain team. Around 70 per cent of participants had worked in their profession for over 10 years, 10 per cent between six and 10 years and 20 per cent between two and six years.

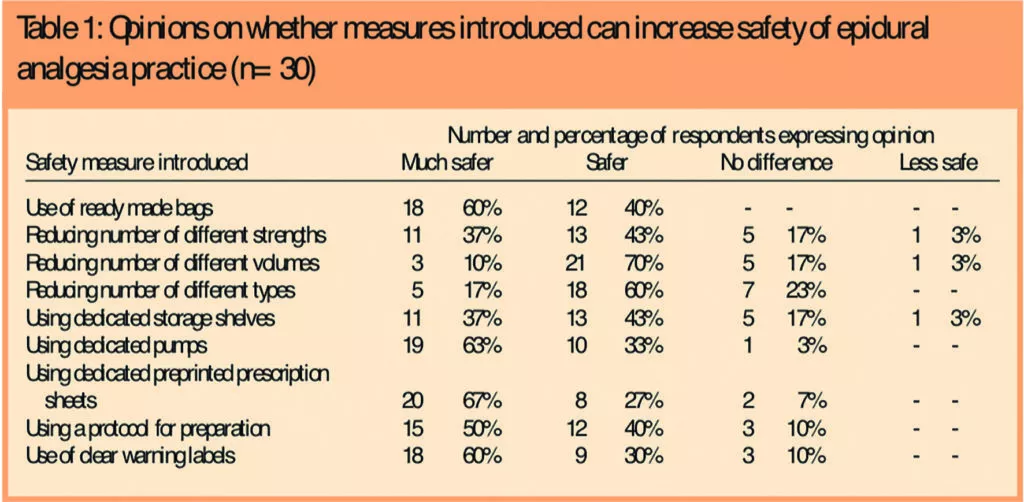

The results are in two sections. In Table 1 opinions about the specific measures introduced at Lewisham are given.

Additionally participants were asked to comment on the potential value of further initiatives that might be of value; these were either already in place or had been suggested in the literature (see Table 2).

The introduction of ready-made bags was thought by all subjects to make the techniques “safer” or “much safer”. One respondent thought that dedicated pumps made no difference, while the remainder (97 per cent) thought they improved safety. Clear warning labels on the packaging were also thought to improve safety by a large majority (90 per cent), with the minority believing it made no difference. Restriction in the different strengths, types and volumes of epidural anaesthesia products was thought to improve safety by 70 per cent, 77 per cent and 80 per cent of respondents, respectively, although one respondent believed that restriction of strengths and types made things less safe.

A potential initiative cited by five respondents (17 per cent) was the design and introduction of a connection system for spinal drug administration that was incompatible with both intravenous and nasogastric systems.

Thirteen respondents (43 per cent) had witnessed or been involved in an error or near-miss incident. The factors that contributed or were thought to contribute were:

- Difficulty in reading labels (three respondents

- Incorrect labelling (six respondents)

- Wrong storage (two respondents)

- Similar packaging (five respondents)

- Incompatible administration sets (two respondents)

- Calculation errors (three respondents)

- Other reasons, including human error (10 respondents)

The largest group is ‘other’ and respondents reported that human error was responsible for the majority of these.

Seventeen respondents (57 per cent) had not witnessed or been involved in an error or near-miss incident. The factors that they thought were likely to contribute to such incidents were:

- Difficulty in reading labels (four respondents

- Incorrect labelling (10 respondents)

- Wrong storage (four respondents)

- Similar packaging (10 respondents)

- Incompatible administration sets (two respondents)

- Calculation errors (12 respondents)

- Difficulty in reading labels (three respondents

- Incorrect labelling (six respondents)

- Wrong storage (two respondents)

- Similar packaging (five respondents)

- Incompatible administration sets (two respondents)

- Calculation errors (three respondents)

- Too many products available (two respondents)

- Other reasons, including human error (10 respondents)

Overall 67 per cent of subjects believed that the series of initiatives introduced in 2001 made the epidural anaesthesia technique “much safer” in the hospital, 27 per cent thought they made it “safer” and 7 per cent thought they made no difference. No participant thought the initiatives introduced made the technique less safe.Suggestions for what would improve safety further included:

- Ongoing training, especially on how to programme the epidural pumps and in the preparation of solutions (seven respondents)

- Dedicated syringes and systems for epidural use (six respondents)

- Regular reviews of the service and critical incidents (two respondents)

- Differently coloured labels for different strengths (two respondents)

- Ready-made diamorphine solutions (two respondents)

- More user-friendly pumps (two respondents)

- Increased support on wards (two respondents)

- A 24-hour pain team (two respondents)

- More pumps available on wards (two respondents)

- Clearer labelling on pharmaceutical pack-aging (one respondent)

The two commonest suggestions (provision of ongoing training of staff and having a dedicated spinal administration system that is incompatible with intravenous and nasogastric systems) were particularly popular among nurses and consultant anaesthetists, respectively.

Discussion

Most of the strategies used were relatively simple to introduce. Ready made bags and syringes are available from a number of licensed and licensed specials manufacturers. Restricting availability to only those areas that use the products minimises the chance of epidural analgesic bags being used inadvertently instead of a bag of crystalloid. Further restrictions were made so that the obstetrics department only has 250ml bags, whereas other areas have 500ml bags. In obstetrics the quantity required for the duration of treatment is considerably less than 500ml but, more importantly, 500ml bags of crystalloid are routinely used while elsewhere the use of 1L bags is standard. Restrictions on the strengths available reduce the chance of the wrong strength being prescribed, prepared or administered. Restricting storage to CD cupboards means that as well as epidural preparations being unlikely to be selected inadvertently for a crystalloid bag, the practitioner must actively obtain the product, and this introduces a warning of the high risk nature of the product.

The use of dedicated infusion pumps for epidural infusion was highly rated, but this is a high resource solution, not only due to the cost of the pumps but to the training need for the staff to use them safely and effectively. A number of nurses and operating department assistants commented on the fact that the pumps were complex to use and this constituted a risk in itself. A common theme from these respondents was the need for comprehensive training in the use of the pumps, with frequent updates.

Although the initial purchase costs of dedicated pumps may be significant, in the context of the potential cost of a misadventure they become less important. However, the ongoing training needs identified, which are not presently being adequately addressed, represent a resource implication where further ongoing investment is required.

Large, clear, bright yellow labels are now attached to bags with the warning “For epidural use only” before they leave the pharmacy. This gives a strong visual warning of the bag’s contents. In future it may be good practice for manufacturers of these products to use these types of labels rather than have the pharmacy service apply them at the time of supply.

Colour coding of both syringes and labels, which is not used, was supported by many participants as having the potential to improve safety (80 per cent for syringes and 83 per cent for labels). This is a common theme in anaesthetic practice, with standard colours for drugs in anaesthesia recommended by the Royal College of Anaesthetists.6 A recent survey of anaesthetists7 revealed that 94 per cent believed that a standardised colour code should be introduced in the UK. In our study, however, despite the large number of participants advocating this when presented with the option, only two suggested that it might further improve safety. However, at least one commentator has argued8 that this may not necessarily contribute to patient safety because colours themselves will have to be remembered. In addition, there are serious limitations in the numbers of colours, shapes etc that can be used when the range of drugs, concentrations and volume available is considered.

The commonest suggestions to improve safety further came exclusively from two groups. The nurses working in recovery and in surgical high dependency unit advocated ongoing training, particularly in the use of the dedicated pumps and in the preparation of solutions that were not available ready made from pharmacy. Pumps need to be programmed using a multiple step process which could cause confusion among users.

Diamorphine, which continues to be used by some clinicians, is not chemically stable in solution so bags have to be prepared immediately before use. Although nurses felt competent in the process of preparation, they wanted extra training in areas they found difficult, such as calculating the patient’s dose and quantities of constituents, especially for those practitioners who prepared epidurals relatively infrequently.

The consultant anaesthetists on the other hand advocated dedicated administration systems, ie, designing connectors that could only fit epidural cannulae and be incompatible with both intravenous and nasogastric systems. There is a distinct possibility that they were influenced by a similar concept introduced a few years previously to prevent nitrous oxide being administered inadvertently instead of oxygen, which had led to fatalities.9

The continued use of diamorphine means that the safety controls introduced are not fully applied to its use. Although some of the risks are managed through the use of preprinted prescriptions, standardised bags of bupivacaine used as diluent, and dedicated pumps and giving sets, risks associated with reconstitution remain. By implication the use of diamorphine epidural infusions poses a greater risk than using commercially available standardised solutions. Unless diamorphine use is reduced by switching to more stable drugs such as fentanyl or morphine these risks remain. Apart from reviewing the use of diamorphine, continuing use means that there is a need for a new presentation or some technological solution to minimise risks associated with reconstitution. Recent shortages in the availability of Diamorphine have greatly reduced its use, but whether this will continue when availability is restored is not known.

This study used a qualitative technique to research the effects of a number of changes to practice. Ideally, a quantitative study looking at the incidence of errors and near misses before and after the changes introduced in 2001 would reveal the precise impact of the changes. However, this was not feasible for a number of reasons. First, the incidence of actual errors, as reported through clinical incident reporting, is low (probably reflecting some degree of under-reporting) and near misses are rarely identified. Therefore detection of any significant change is unlikely. Also in the intervening period other factors may have impacted on practice including personnel changes.

Therefore we decided at an early stage to use a sociological method to determine the perceptions and opinions of the major stakeholders in the use of this technique. Since the sample was relatively small (37), we decided that a structured interview would be more effective than a postal questionnaire for obtaining a reasonable response. The response rate of 81 per cent supports this as an effective choice. A disadvantage of interviews as a research method is that the Hawthorn effect can bias findings10 as the subjects are aware of the study and its purpose. To minimise this, the interview schedule was standardised and all participants interviewed by the same researcher (IO) who, as a pharmacy student, was not a member of the hospital staff. The pilot work enabled the interviewer to become comfortable and conversant with the process and this should also have minimised bias, particularly in the initial subjects interviewed. All the interviews were conducted in a setting of the interviewee’s choice. Finally, at the beginning of the interview participants were asked to be honest in their responses and were assured that all information obtained would be kept strictly confidential.

Another potential source of bias was that practitioners may have felt threatened by questions about potential and actual errors. The strategies outlined above should have minimised this. The fact that a considerable number of practitioners were willing to discuss these suggests that this source of bias was minimal.

A final limitation is that the work was done on a single site with a small number of individuals, albeit with a high proportion of the relevant population. The number and range of risk reduction strategies introduced in other hospitals, and their acceptance, will vary. However, the high level of acknowledgement that the strategies introduced at University Hospital Lewisham led to “safer” or “much safer” epidural analgesic use suggests that introduction of these strategies at other hospitals will have similar effects. In addition some of the strategies are similar in principle to those recommended by the National Patient Safety Agency for strong potassium preparations, viz, restriction of availability and control of strengths and storage,11 and by the Department of Health for the safe use of intrathecal cytotoxics.12

Conclusion

The strategies introduced to minimise the risks associated with epidural analgesia at University Hospital Lewisham are thought to contribute to patient safety by the majority of practitioners who regularly use the technique.

About the authors

Ijeoma Orunta, MPharm, was a final-year pharmacy student at King’s College London, and is now a preregistration trainee at King’s College Hospital, London.

Chris Cairns, MSc, FRPharmS, was director of pharmacy and dietetics at University Hospital Lewisham, London, and is now professor of pharmacy practice at Kingston University, Kingston upon Thames.

Russell Greene, PhD, MRPharmS, is director of undergraduate studies at the King’s College London department of pharmacy.

Correspondence to: Professor Cairns, Room 226, Kingston University, Penrhyn Road, Kingston upon Thames, Surrey KT1 3EE (e-mail C.Cairns@kingston.ac.uk)

References

- Department of Health. Building a safer NHS for patients. London: The Stationery Office; 2001.

- Department of Health. An organisation with a memory. London: The Stationery Office; 2000.

- Audit Commission. A spoonful of sugar: medicines management in NHS hospitals. London: The Commission; 2001.

- Block BM, Liu SS, Rowlingson AJ, Cowan AR, Cowan JA, Wu CL. Efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia: a meta-analysis.JAMA 2003;290:2455–63.

- Browne A. Patient killed in hospital after injection blunder. The Observer. 11 February 2001.

- Syringe labelling in critical care areas. Bulletin of the Royal College of Anaesthetists 2003;(19):953.

- Christie IW, Hill MR. Standardized colour coding for syringe drug labels: a national survey. Anaesthesia 2002;57:778–817.

- Wildsmith JAW. Doctors must read drug labels, not whinge about them. BMJ 2002;324:170.

- Jackson T. Not again! BMJ 2001;322:247.

- Mayo E. The human problems of an industrial civilization. New York; MacMillan: 1933, Ch 3.

- National Patient Safety Agency safety alert: potassium chloride concentrate solutions (PSA 01). London: NPSA; 2003.

- HSC 2003/011.Department of Health. Updated national guidance on safe administration of intrathecal chemotherapy (HSC2003/011). London: The Department; 2003.