Abstract

Aims

To describe medicines management and pharmacists’ involvement in oral anticancer medicines (OAMs) services and prepare standards for prescribing, dispensing, supply, administration and monitoring of OAM use.

Design

A survey of oncology pharmacists plus a stakeholder consultation for developing standards.

Subjects and setting

56 responses received from a sample of 108 hospital pharmacy departments.

Outcome measures

To find out how the key components of medicines management are applied to OAMs, the service developments needed and the extent of pharmacist involvement in OAM clinics. To prepare standards for the prescribing, dispensing, supply, administration and monitoring of the use of OAMs.

Results

The results show high awareness of OAM issues. Most trusts include OAMs in policy, but few have specific policies for OAMs. Although all trusts used regimen-specific preprinted prescriptions or electronic prescribing, only 27% included all OAMs. Handwritten prescriptions are still prevalent in outpatient haematology clinics. Few trusts give additional training to staff handing out OAMs and many do not monitor patients between hospital visits. Most respondents indicated that patients should be managed in the same way as those on intravenous anticancer medicines. OAM clinics involving pharmacists are rare. Almost all pharmacists expressed a desire for greater involvement in managing OAM patients.

Conclusions

Specific standards are needed to support OAM management and improve patient safety. The research reinforces the findings of the National Patient Safety Agency safety alert, “Risks of incorrect dosing of oral anticancer medicines”.

Recent years have seen a huge growth in the use of oral anticancer medicines both in hospitals and, more recently, in the community. Traditionally, most therapies for solid tumours were given intravenously (IV). With the exception of haematological malignancies, few medicines were suitable for oral administration. Most chemotherapy was supplied as ready-to-administer IV products prepared by specially trained hospital pharmacy staff. The number of medicines available and in development is increasing. Table 1 lists those currently available in the UK.

The increased use of oral anticancer medicines (OAMs) offers advantages to patients and healthcare professionals. It can free pharmacist and nurse time and ease capacity pressures.1

Although standards for dealing with IV chemotherapy are clearly defined in the NHS “Manual for cancer services”,2 there was increasing anecdotal evidence of oral anticancer therapies being handled differently from IV chemotherapy. Research in America has shown that US cancer centres have adopted few of the safeguards routinely in place for IV chemotherapy.3 There is a lack of research evidence on the safety practices associated with the use of OAMs in the UK.

The safe use of OAMs is a hot topic for the NHS. The National Patient Safety Agency issued an alert to all healthcare professionals in January 2008 entitled “Risks of incorrect dosing of oral anticancer medicines”.4 It highlights the potential for fatal outcomes if incorrect doses of oral anticancer therapy are prescribed, dispensed or administered, stating that there have been three deaths and more than 400 patient safety incidents involving oral anticancer therapy in the past four years. It continues: “Half of these reports concerned the wrong dose, strength, frequency or quantity of oral anticancer therapy. A large number of these incident reports involved capecitabine.”

These concerns indicate a clear need to define how UK pharmacists practise medicines management. Although pharmacists have a key clinical role in this area, little is known about how they have developed their role.

Medicines management seeks to maximise health gain through the optimal use of medicines. It encompasses all aspects of medicines use, from prescribing to the ways in which they are taken, or not taken, by patients.

There have been limited reports in the literature of pharmacists providing extended services to patients receiving OAMs.5,6 This research project sought to provide evidence of current UK medicines management and pharmaceutical care of OAMs and to use the data gathered and discussion generated to make recommendations for future practice, highlighting the pharmacist’s role.

The accepted definition of “OAM” covers all drugs with direct antitumour activity, orally administered to cancer patients, including traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy such as capecitabine, hydroxycarbamide, chlorambucil, small molecule treatments such as imatinib, erlotinib and sunitinib, and other agents such as thalidomide or lenalidomide. It does not include hormonal or antihormonal agents such as tamoxifen and anastrazole.7

The British Oncology Pharmacy Association recognises the risks with the medicines management of oral chemotherapy and has issued a position statement on “The safe practice and pharmaceutical care of patients receiving oral anticancer chemotherapy”.7 BOPA has traditionally set the standards for UK oncology pharmacists and provides a forum to develop practice and raise standards.

Although influential, BOPA is a practice interest group and its advice is not mandatory for NHS trusts. There is therefore concern over the application of the advice within its position statement and its influence on practice.

BOPA has now been joined by the UK Cancer Network Pharmacists Forum, a group that brings together all pharmacists employed by cancer networks in the UK. BOPA and the CNPF are looking at the medicines management of OAMs and this research was undertaken to support their work.

Methods

The research question was: “How do pharmacists contribute to the medicines management of patients on oral anticancer medicines in the NHS?”

The research project had two phases. In phase I a survey using a written questionnaire as the data collection tool was used to offer a non-experimental descriptive design that described reality. The research was undertaken from March to November 2007.

In phase II a series of key stakeholder interviews, followed by wide consultation, was used to inform the design and preparation of standards for the prescribing, dispensing, supply, administration and monitoring of the use of OAMs in the north-east of England.

A small focus group of oncology pharmacists was chosen to help design and refine the questionnaire and target areas of particular interest. The main areas of debate raised by the focus group was the inclusion or exclusion of nurse-led developments with OAMs. It was recognised that the research may not give a true picture of the overall development of OAM-specific clinics because many were run by oncology nurses rather than pharmacists. However, it was decided that the focus of the research should be on pharmacists.

The focus group was keen for the questionnaire to raise awareness of medicines management issues and the development of pharmacist OAM clinics. Following comments from the group, the questionnaire was piloted in five hospitals. The pilot raised some minor issues about the clarity of the questionnaire, which was then amended accordingly (eg, the question order was changed). The pilot showed that the questionnaire took 10–15 minutes to complete on average.

The questionnaire consisted predominantly of closed questions of the yes/no or select-from-a-list variety. Where appropriate, sections for comments were included. The focus group proved useful in selecting areas for comment.

A Likert scale was used in the questions to assess pharmacists’ opinions on the value of service developments. The questionnaire sought to collect data on key medicines management domains, looking specifically at pharmacists’ roles. The questions were grouped in six main areas:

- Policies and procedures

- Prescribing

- Designing services around patients

- Management

- Oral anticancer medicine clinics

- Development of pharmaceutical care

- Resource requirements for service development

Distribution of the questionnaire was arranged through members of the CNPF, who agreed to champion the questionnaire to the cancer centre and cancer unit hospitals within their cancer networks. The sample size of the final distribution list was 108. Returns were received by e-mail and post.

An Excel spreadsheet database was constructed to collate and analyse the responses. Questionnaires were coded in a numerical sequence according to date received, with each hospital assigned a number. The spreadsheet was used to quantify answers and show basic frequencies of response.

Statistical analysis was considered — in particular, a chi-squared test to evaluate whether the differences between proportions in the yes and no answers could show statistically significant variances. However, on consideration of the data collected this was not deemed appropriate. This was confirmed after seeking advice from a statistician, who advised that a simple report of frequencies of answers with discussion of potential reasons for findings was the best approach with this dataset.

Following the completion and analysis of the collected data, the results were used to inform the content of the second half of this research project, which was to produce standards for medicines management of OAMs. Standards provide a reference point against which trusts can measure their OAM services. More importantly, they can be audited. In December 2007 the North of England Cancer Network published version one of “Standards for the safe use of oral anticancer medicines”.

Results

Fifty-six responses were received from the sample size of 108, a return rate of 52 per cent; 34 per cent (19) of the respondents were from cancer centre hospitals and 66 per cent (37) from cancer unit hospitals.

Policies and procedures

Ninety-five per cent of respondents indicated awareness of the 2004 BOPA position statement on oral anticancer chemotherapy. OAMs were included in 72 per cent of trusts’ medicines or chemotherapy policies. Handling, dispensing and labelling were well covered by local policy, but 55 per cent of trusts did not have a separate prescribing policy for oral chemotherapy.

Prescribing

Twenty-seven per cent of respondents had electronic prescribing systems that included oral chemotherapy agents but only 7 per cent included all oral agents. The 73 per cent that did not have electronic prescribing all used electronically generated preprinted prescriptions, but only 20 per cent had preprinted prescriptions available for all regimens. Only 48 per cent of respondents reported that OAMs traditionally used in haematology were treated the same way as newer OAMs used in solid tumours. Among the comments recorded to explain this, a recurring theme was that OAM regimens for haematology were prescribed by hand on standard outpatient charts. Others said that haematology was excluded from electronic prescribing systems.

Designing services around patients

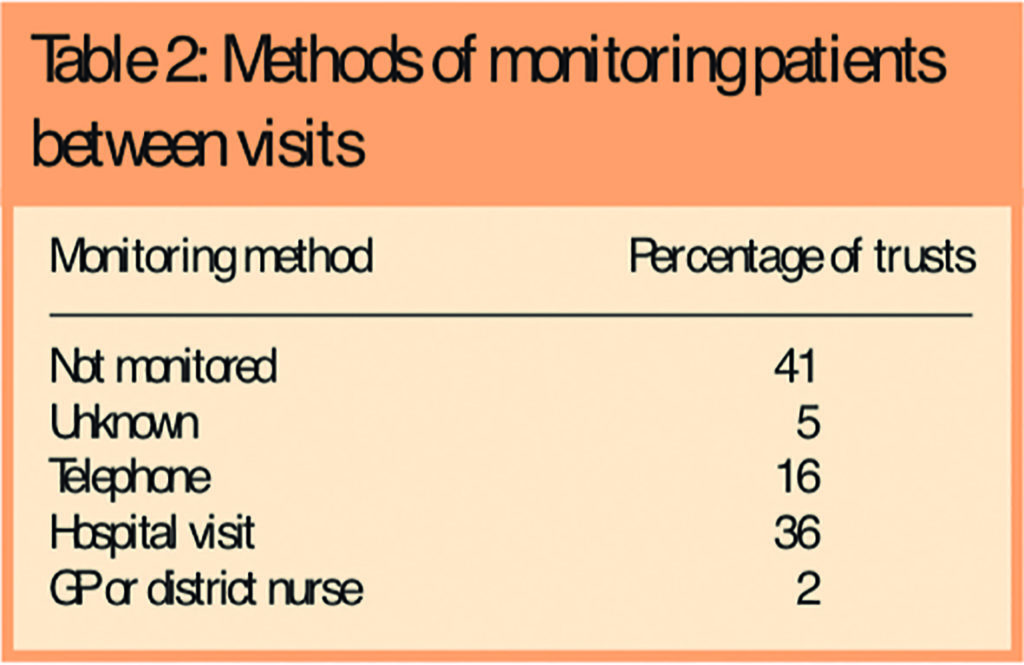

Pharmacy and nursing staff shared the responsibility for giving out OAMs to patients. Most respondents reported that qualified staff — eg, technicians (73 per cent), pharmacists (84 per cent) and nurses (87.5 per cent) — gave out the medicines. Doctors and pharmacy assistants were infrequently involved (12.5 per cent and 11 per cent, respectively). Few respondents (18 per cent) reported training for staff who gave out OAMs. Two-thirds of patients carry information about their OAMs and information was provided to most patients (86 per cent). OAM patients are not routinely monitored between visits to collect medicines. When they are, hospital visit and telephone contact are the most common method (Table 2).

Management and leadership

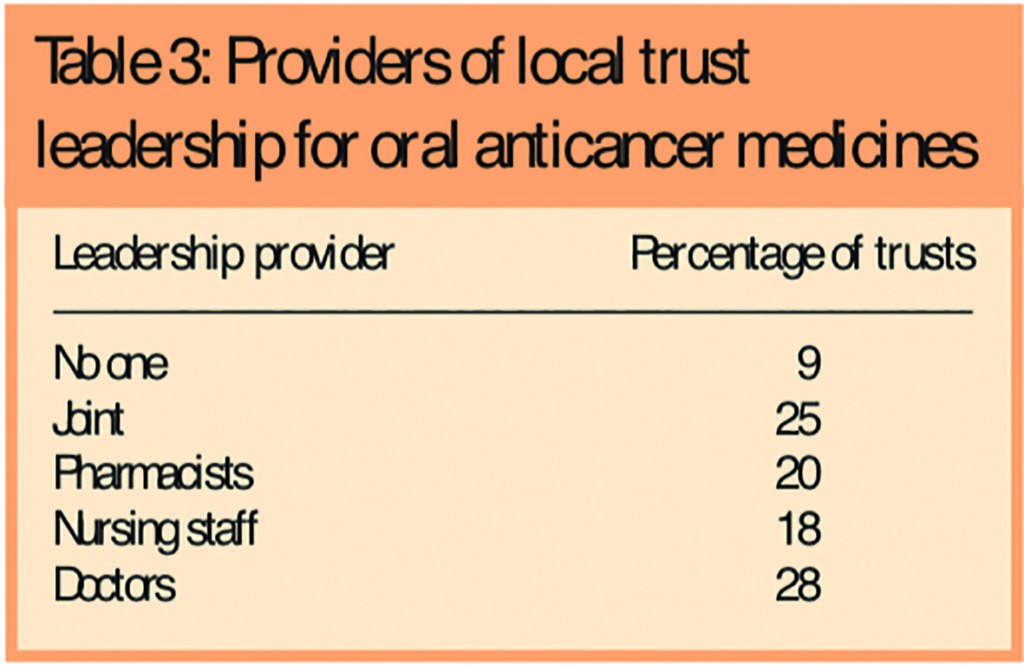

Table 3 shows which professional groups provide the local trust leadership on OAMs. Patient pathways for OAMs were poorly defined, available in only 11 per cent of trusts.

Respondents were asked how OAM patients should be managed. Most (59 per cent) said the same as IV chemotherapy. Ninety-six per cent of respondents saw oral chemotherapy as an area that needed developing in their trust and 94 per cent saw a need for increased pharmacist involvement in this area.

When asked who was responsible for developing the pharmacist’s role in oral chemotherapy, 45 respondents (80 per cent) thought it was a joint responsibility between BOPA, cancer networks and individuals at trust level, while nine (16 per cent) thought it was solely the responsibility of individuals at trust level.

Development of OAM clinics

Only 20 per cent of trusts dealt with OAMs in separate clinics, and some had mixed IV/OAM clinics. Of the OAM clinics, 11 were nurse-only and eight (14 per cent) involved pharmacists.

With only 14 per cent of respondents reporting pharmacists’ involvement in OAM clinics it was difficult to draw any firm conclusions on how these services are developing other than that, at the time of the data collection, they were rare. Pharmacists who have developed this role undertake tasks such as counselling patients, prescribing supportive care (as supplementary prescribers) and monitoring the effects of treatment.

Pharmacy colleagues working in trusts viewed the development of the role of pharmacy in OAM as desirable but not essential. However, 96 per cent thought that increased pharmacist involvement in oral chemotherapy is a good use of resources. Most clinics were set up within current resource.

Resources needed

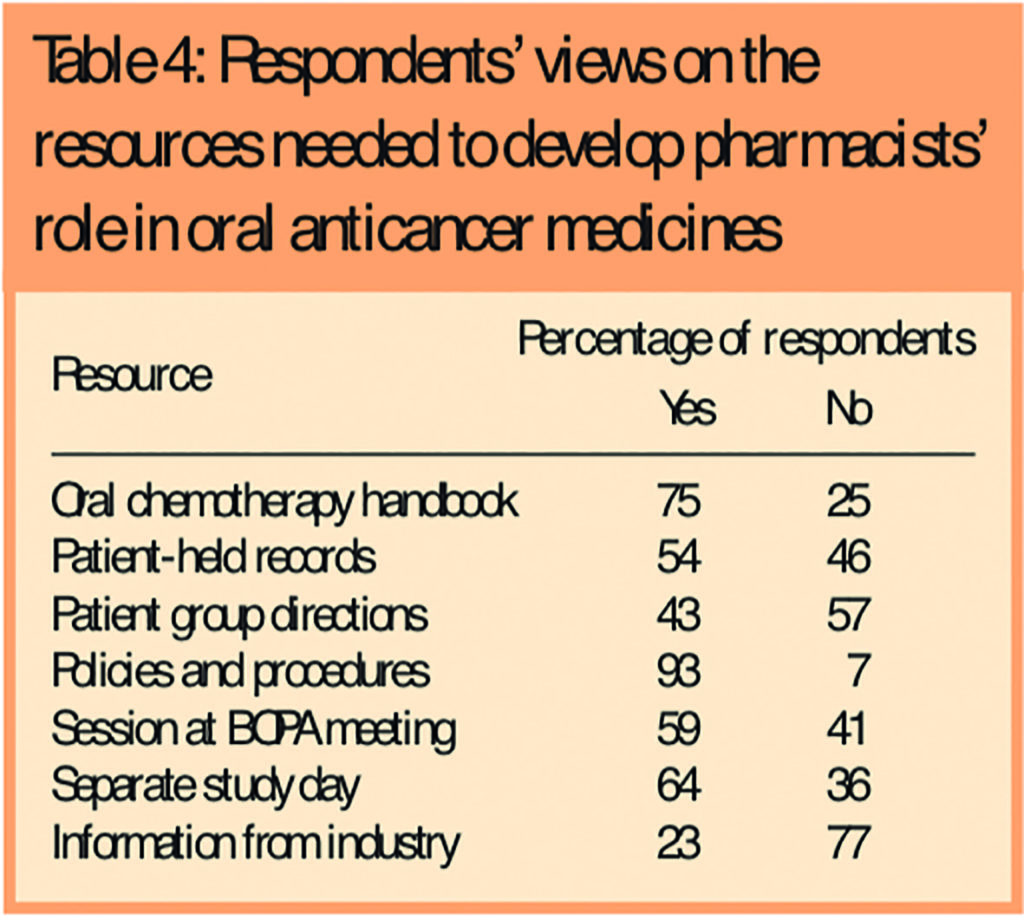

Table 4 shows the resources respondents believed were needed to develop pharmacy’s role in OAMs.

Discussion

OAMs have the same potential for risk as IV medicines in terms of both managing treatment-related toxicities and, perhaps most importantly, greater potential for medication errors if OAMs are not handled to the same standard as intravenous medicines.

As the number of oral medicines available for cancer treatment has grown, there has been a corresponding growth in clinical incidents involving OAMs. Little was known about the practice of medicines management and extent of involvement of pharmacists in managing patients on OAMs.

The results of this research provide useful insight into management of these medicines and supports the NPSA’s conclusion that this is an area of high risk where there is a need to develop safe practices to protect patients.4

The research focused on secondary care because that is where most of these medicines are dispensed. However oral anticancer medicines are increasingly being used in the community. The NPSA reported that during 2006–07 nearly 18 million doses were used in hospitals and six million doses used in the community in England.

Before the NPSA alert, the 2004 BOPA position statement on safe practice and the pharmaceutical care of patients receiving oral anticancer chemotherapy was the only national good practice guideline for OAMs. The results confirmed that this document has been successfully promoted and taken on board by pharmacists in the UK, since only 5 per cent of respondents were not aware of it.

The BOPA guidance provides a useful template for trusts to look at the way they manage their OAMs. However, they should not rely on the BOPA position statement alone but should include OAMs in their own clinical governance policies and procedures. Most trusts have included oral chemotherapy in their medicines or chemotherapy policies, although most commonly as a small part of main policy. Few have specific policies highlighting particular challenges with OAMs. The NPSA recognised this and instructs healthcare organisations to prepare local policies and procedures to describe the safe use of OAMs.

There is a lack of published data on best practice with OAMs. Most articles focus on benefits and compliance issues. A paper in the BMJ in early 2007, looking at US cancer centres, concluded: “The oncology community must define safe medication practices for oral chemotherapy, develop practice guidelines and accelerate their adoption.”3 The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia has published standards of practice for the provision of oral chemotherapy which focus on pharmacy practice but recognise that “oral chemotherapy must be subject to the same stringent prescribing and checking procedures as chemotherapy administered by other routes.”8

This reinforced the belief that there is a definite need for a set of comprehensive standards to inform best practice which were developed in the second part of this research project. The need for standards can also be justified by the changing clinical environment with regards to OAMs. This is a growing area and one of great interest for pharmaceutical companies.

Patient preference has been a strong driver for developing OAMs. The use of oral chemotherapy can empower patients and give them a feeling of control over their disease. A scenario-based questionnaire of 103 patients likely to receive palliative chemotherapy found that 89 per cent preferred oral treatment, provided it was as effective as intravenous therapy.9 In a cross-over patient preference trial comparing capecitabine with IV 5-fluorouracil, 57 per cent of patients preferred the oral therapy.10 The main reason for preference was for home rather than hospital-based treatment.

The need to develop separate standards for OAMs had been questioned on the basis that Department of Health cancer standards cover these medicines. However, this research demonstrates that OAMs are handled differently to IV medicines. Most respondents (59 per cent) indicated that oral chemotherapy patients should be managed in the same way as IV chemotherapy patients. But there was some diversity of opinion, with some taking the view that OAMs need less involvement from nursing and pharmacy staff than IV medicines.

Fourteen per cent of respondents indicated that OAMs should be handled as outpatient medicines. It is possible that, as service models develop, the prescribing of these medicines may move away from secondary care. Therefore specific standards need to be developed for inpatient prescribing, outpatient prescribing, non-medical prescribing, prescribing for external healthcare organisations and primary care prescribing.

Hospital and cancer network pharmacists must work with their primary care and community colleagues to support them and ensure best practice as services are developed. Equally, primary care pharmacists must be alert for prescriptions for OAMs and ensure they have access to the written protocols.

Electronic prescribing of chemotherapy has been promoted as a key development in the safety and management of chemotherapy services in the UK. Many cancer networks have invested in electronic prescribing systems. The survey showed that 27 per cent of respondents had electronic prescribing systems which included oral chemotherapy agents but only 7 per cent included all oral agents.

Although an electronic prescribing system may improve the safety aspects of OAMs, the benefits can only be realised if all medicines are included. In the absence of an approved and validated electronic prescribing system, the use of computer-generated preprinted prescription forms that detail each individual drug regimen is essential to ensure accuracy and clarity. The research showed that all those sites that did not use electronic prescribing used computer-generated, regimen-specific preprinted prescription forms.

Unfortunately, many sites reported that preprinted prescription forms were not available for chemotherapy medicines traditionally used in haematology. Fifty-two per cent of respondents reported haematology medicines were not treated in the same way as newer oral chemotherapy agents used in solid tumours.

This highlighted that one of the greatest areas of risk with OAMs appears to be outpatient clinic haematology prescribing because of the large number of complex, infrequently used chemotherapy regimens for haematological malignancies that have traditionally been handwritten on “outpatient” prescriptions. The NPSA data on patient safety incidents showed that 56 per cent of reported incidents involved medicines routinely prescribed in “outpatient” departments by haematologists.

Of the remaining safety incidents 42 per cent involved capecitabine. This may be a reflection of the relatively high use of capecitabine compared with some of the more traditional OAMs, but still gives cause for concern as to whether the medicines management of this drug is adequate.

OAM regimens can be complex. It is therefore crucial to have medicines information resources specific to oral chemotherapy regimens — eg, regimen protocols — and 89 per cent of respondents reported having such information in place. Although pharmacists traditionally use the British National Formulary, our standards document does not recommend it as a primary source of anti-cancer drug prescribing information. The BNF gives basic drug dosing information but does not give detailed advice about oral medication in combinations.

The NPSA alert focuses on the need for all OAMs to be prescribed only in the context of a written protocol and treatment plan. Access to these protocols is particularly important for non-specialist practitioners in primary care. Suggested standards for OAM prescription writing are set out in the Panel.

Panel: Suggested standards for OAM prescription writing

This standard defines the information that should be included on OAM prescription forms, as follows:

- Patient details, including height, weight and body surface area

- Protocol or regimen name

- Drug names (generic), and doses (both as mg/m2 or per kg and the final calculated dose)

- Frequency of administration

- Number of days or doses to be dispensed, expressed in long hand — eg. “for 3 days”rather than “3/7” (see note below)

- The intended start date and exact duration of treatment including either stop date or the word “ONLY” to indicate that the medicine is not continuous — eg, “capecitabine start on 1/1/08 for 14 days ONLY”

- For continuous treatment, the intended review date

Note: Abbreviations are not to be used. In particular, the way of expressing the number of days or doses was highlighted as critical during the consultation process. Traditionally prescribers have used abbreviations or figures such as “1/7”, which has led to errors whereby medicine was dispensed for one week rather than one day.

Within pharmacy there was inconsistent involvement of trained oncology pharmacists in the processes and a lack of additional training for staff giving out OAMs. Only 18 per cent of respondents reported training in this area. Given the specialised nature of these medicines, best practice would be for the member of staff giving the medicines out to patients to have the expertise to answer any questions patients may pose.

The BOPA 2004 guidelines describe best practice. Pharmacy staff must take responsibility when supplying the OAM to ensure that the recipient fully understands:

- How and when to take the medicine

- What to do in the event of missing doses

- What to do in case of vomiting after a dose

- Likely adverse effects and what to do about them

- Any need for and how to obtain further supplies

- The role their GP is expected to play intheir treatment

- Principles of safe handling, storage and dis-posal

- That if used, medicine spoons or measures should be used once only and then disposed of safely

It is suggested that standards for OAM are designed to follow the patient pathway. Our standards start with prescribing. It covers all aspects of prescribing, including who can prescribe, how to prescribe safely, how to deal with prescribing in different circumstances, in-patient, outpatient, etc. The document then covers in detail dispensing, supply, administration and governance of OAMs.Pharmacists are in an ideal position to manage oral chemotherapy and have increased clinical input, but many different models have evolved in how we manage these patients and currently we have no idea of what constitutes best practice. Of those that have been reported in the literature a nurse-/pharmacy-led capecitabine clinic for colorectal cancer in Glasgow has been shown to be safe and acceptable to patients.5

In training to become prescribers, pharmacists learn new skills in clinical assessment of patients and are able to provide a more complete package of care. However, it must always be remembered that pharmacists are seeking to work in partnership with doctors, nurses and, of course, the patient. The responsibility for developing pharmacists was shown to be shared between BOPA, cancer networks and individuals at trust level. This recognises that there will be individual expert practitioners who should be leading and encouraging their colleagues through their local networks and BOPA

The question of resources needed to develop the pharmacist’s role showed that examples of policies and procedures were the items most needed, followed by an oral chemotherapy specific regimen handbook.

Finally, given the NPSA data showing that six million doses were used in the community, we can conclude that there is a need for further research into the use of OAMs in primary care and in particular the level of support that community pharmacists need when managing patients on these medicines.

Study limitations

It was not possible to draw firm statistically significant conclusions about the practice of medicines management related issues across the entire UK from the data collected. Practices at sites that did not respond may differ from those that did, with a resulting affect on the data set outcomes.

The results do not capture the views of nursing or medical staff, though that was deemed appropriate at the outset, because the research focuses on pharmacy practice. Given the subsequent need to develop a multi-professional standard document for OAMs, this representation was addressed by stakeholder consultation with nursing and medical staff and wide consultation with relevant members of these professional groups.

Conclusion

The results show that the practice in the UK compares favourably with practice in US cancer centres — for example, prescribing is more controlled but safety practices still need developing to protect patients.

This is an area of high risk that needs to improve practices and medicines management to protect patients. Specific standards for OAMs have to be developed to support medicines management and improve patient safety. The NPSA alert in January 2008 set minimum standards for the NHS and focused on the need for access to good written information on the medicines in particular written protocols and treatment plans.

The shift to oral therapy for some groups of cancer patients has implications for their care. The responsibility for delivering the medicine to the patient has moved from the oncology nurse to the patient with self-administration at home. As pharmacists are encouraged to become independent prescribers, those with expertise in cancer medicines have a role in managing the care of patients on OAMs as part of a team alongside their medical colleagues. This is a new direction of travel for pharmacy which will potentially involve community and primary care pharmacists as well as hospital pharmacists. Pharmacist from all sectors should be encourages to work together to define best practice in this high risk area.

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to CNPF members for their help in distributing and collating the questionnaire and to the BOPA committee members who provided advice on the scope of the questionnaire.

About the author

Steve Williamson, MSc, MRPharmS, is consultant pharmacist in cancer services, Northumbria Healthcare and North of England Cancer Network.

Correspondence to: Steve Williamson, Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust Pharmacy, North Tyneside Hospital, Rake Lane, North Shields, Tyne and Wear NE29 8NH.

This original paper was accepted for publication on 4 September 2008.

References

- O’Neill VJ, Twelves CJ. Oral cancer treatment: developments in chemotherapy and beyond. British Journal of Cancer 2002; 87:933–7.

- Department of Health. Manual for cancer services 2004. London: The Department; 2004.

- Weingart SN, Flug J, Brouillard D, Morway L, Partridge A, Bartel S et al. Oral chemotherapy safety practices at US cancer centres: questionnaire survey. BMJ 2007;334:407–11

- National Patient Safety Agency. Risks of incorrect dosing of oral anticancer medicines. Rapid response report, 22 January 2008.

- MacLeod A, Branch A, Cassidy J, McDonald A, Mohammed N, MacDonald L. A nurse-/pharmacy-led capecitabine clinic for colorectal cancer: results of a prospective audit and retrospective survey of patient experiences. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 2007;11:247–54.

- Lumb J. How community pharmacists can help raise public awareness of lung cancer: pharmacy-led oral chemotherapy lung cancer clinic. Pharmaceutical Journal 2007;279:504–5.

- British Oncology Pharmacists Association. Position statement on the care of patients receiving oral chemotherapy. Pharmaceutical Journal 2004;272:422–3

- Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia Committee of Specialty Practice in Cancer Services. SHPA standards of practice for the provision of oral chemotherapy for the treatment of cancer. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2007;37:149–52.

- Lui G, Franssen E, Fitch MI, Warner E. Patient preferences for oral versus intravenous palliative chemotherapy. Journal of Clinical Oncology 1997;15:110–5.

- Twelves C, Gollins S, Grieve R, Samuel L. A randomised cross-over trial comparing patient preference for oral capecitabine and 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin regimens in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Annals of Oncology 2006;17:239–45.