Introduction

Musgrove Park Hospital is a 700-bed acute district hospital that completed around 89,000 finished consultant episodes in 2010. It has approximately 240 surgical beds spread across 10 wards, of which half were allocated to general surgery at the time of the project.

From January 2009 to June 2011, between 96 and 98 per cent of available inpatients received a visit from a clinical pharmacist daily on Mondays to Fridays.The funded pharmacy staff establishment was 50.4 whole time equivalent (WTE) staff. Combined vacancy rates and maternity leave resulted in 44.5 WTE staff being in post during the project. Five pharmacists provided clinical pharmacy services to all surgical patients. No ward-based clinical pharmacy service was undertaken at weekends. (This information is provided by way of introduction for those who might wish to determine whether their own staffing levels are sufficient to attempt a similar project.)

In February 2010, the National Patient Safety Agency published Rapid Response Report 0091[1]

— “Reducing harm from omitted and delayed medication in hospital”. Before this, in 2009, Fleisher et al had[2]

published a paper highlighting the risks of withholding beta-blockers in the perioperative period and specifically the unexpected association with one-year mortality rises. This latter paper was assessed by consultant anaesthetists. They associated unintentional cessation of medicines as being common in the preoperative period. Subsequently pharmacy staff were asked to assess the extent of missed beta-blockers and if necessary to determine how the situation might be rectified.

Because it was necessary to act upon the recommendations of the NPSA report, it was decided that both concerns might be addressed together.

A small group of pharmacists identified the common factors and causes associated with missed doses (see Panel). It was surprisingly easy to identify these anecdotally and from incident investigations and complaints. Missed doses associated with incomplete drug histories and inaccurate prescribing were not considered to be a major factor because 92 to 98 per cent of medicines reconciliations were completed within 24 hours of clinical pharmacy service availability.[3]

Also more than 95 per cent of medicines administration record (MAR) charts were reviewed by ward pharmacists daily on Mondays to Fridays.

Panel: Reasons

Reasons for missed doses of prescribed medicines on wards

- Unfamiliarity with ward stock list

- Unfamiliarity with general stock lists (other wards and emergency drug stock list)

- Drug not on ward (or any stock list)

- Unfamiliarity with medicines management procedures (more common with bank and agency staff)

- No further effort to avoid a missed dose is taken due to lack of appreciation of potential clinical impact or perceived difficulty obtaining the drug

- Perception that the dispensing turnaround times were too slow to meet ward requirements

- Lack of adherence to policy

- Misinterpretation of what is meant by “nil by mouth”

- Reliance on historical use of ward stock ordering books

- Delivered stock not put away in a timely fashion (therefore remaining in the delivery site)

- Failure to record administration activity on medicines administration charts (resulting in blank entries)

- Patient not on ward at the time of the drug round

The initial list was divided into two groups of factors. The first group (1–6, see Panel) related to the availability of drugs during ward drug rounds and included situations where:

- The required drug was unavailable on the ward

- Staff believed the drug was not available but after investigation it was found to be both onthe ward stock list and in the stock cupboards

- Staff incorrectly concluded that the required drug would not have arrived from pharmacy at the time of the drug round and hence did not check the medicines deliveries before entering “unavailable” on the MAR chart

The second group (7–12, see Panel) related generally to misinterpretation or misunderstanding of existing medicines management policies and guidance.The pharmacist group then examined a short series of surgical MAR charts to confirm their beliefs as to why doses were intentionally but inappropriately withheld. It quickly became apparent that the most common documented reason by far was given as “patient NBM” (“nil by mouth”).This occurred most frequently in general surgery.

It was therefore decided to begin two separate projects. One was to focus on reducing missed medicines doses across the entire trust by addressing factors 1 to 6. The second project, the focus of this paper, would concentrate on reducing missed doses in the preoperative period in general surgery by addressing the misinterpretation of what was meant by “nil by mouth”. This second project was regarded as an audit and consequently ethics committee approval was not required.

Method

A set of simple potential solutions was proposed by the group:

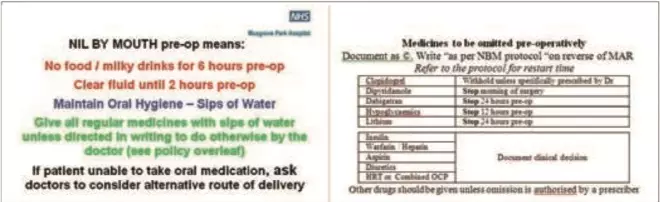

- Pre-existing bedside “nil by mouth” notices would be updated and the information contained on them clarified. Specifically, they would now detail the patients’ oral intake status and provide a summary of the trust policy “Perioperative management of patient’s usual, preoperative medications”.

- All general surgical ward nurses would be issued with credit card-sized summaries of the trust policy (see Figure 1). These would attach to staff uniforms together with the staff members’ identification badges and would be carried at all times while on duty.

- Each nurse on duty would receive a two- minute briefing about the new bedside notices and the summary card, the key message being that when patients are “nil by mouth”, usual oral medicines should be administered with sips of water as per the trust policy.

Figure 1: Credit card-sized summary of the trust’s preoperative nil by mouth policy

After the introduction of these interventions across the general surgical wards, it was proposed that formal incident forms should be completed by ward pharmacists with each newly identified inappropriate missed dose.

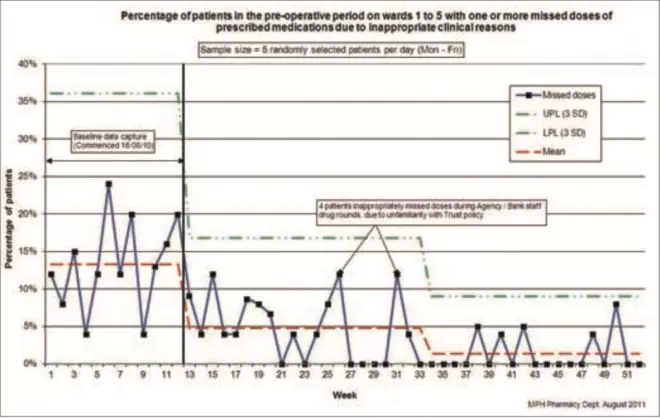

The project therefore consisted of testing, modifying then implementing the “solutions” while measuring their impact on the frequency of missed doses and capturing these data in a run chart[4] (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: An example of a run-chart

Initially a pilot ward was selected based on the likelihood of ward staff and the project team being able to work effectively together to produce the positive outcomes desired.This is an accepted approach when undertaking improvement work. The rationale is that if simple changes cannot produce positive results in a favourable environment, then it is unlikely that positive results will occur in a less favourable environment. Senior ward nursing staff and their matron, together with the surgical anaesthetics leads, were briefed about the project goals and how the project would be run. This group then acted as the high level project sponsor. Their purpose was to give authority to the activities of the project group when implementing changes on various surgical wards. Regular email communication allowed key personnel to be informed of the planned tests of change, results and obstacles to progress.

At the beginning of the project, baseline missed dose data were collected across all five general surgical wards (121 beds) even though the project was to begin on a pilot ward. A random number generator was used to select five patients each day on Mondays to Fridays. A pharmacist would then examine those patients’ MAR charts for any indication that a medicine dose had been inappropriately withheld. Each pharmacist collected the data from the previous day’s MAR. Patients were considered to have inappropriately experienced an episode of missed medication in the following circumstances:

- When one or more missed doses were recorded but the decision to omit did not comply with the trust “nil by mouth” policy

- If there was a failure to document a clinical reason for withholding the dose and hence a failure to comply with the general drug policy

- If the space on the MAR intended to record the administration of the drug was left blank

At the end of each week, the collected data were collated and plotted as a single point on the run chart. It was expressed as a percentage of patients inappropriately missing one or more doses in that weekly sample. (For example, of the 25 patients audited for missed doses each week, if five were found to have experienced one or more missed doses, 20 per cent [5/25] of the patient sample was recorded as inappropriately missing one or more doses of medicines for that week.)

As the run chart grew, eventually it became possible to analyse it using statistical process control techniques.[4] This made it possible to determine whether implemented interventions were having a statistically significant effect on the rate of missed doses over time.

While baseline data were being collected, PDSA (plan, do, study, act) rapid cycle testing[5]

was used on the pilot ward to develop or fine tune this bundle of interventions. For instance, the clarity of both the bedside notice and policy summary card were tested in several cycles for understandability by nursing staff. After three or four test cycles, the bedside notice, summary card and instructional briefing were considered suitable to introduce onto the pilot ward.That is, a new notice was placed by each bed and every ward staff member received both a summary card and an instructional briefing. This, too, was considered to be testing, and further minor changes were made following feedback from nursing staff on the pilot ward.

Once the first three changes were implemented on the pilot ward, similar high level sponsorship was sought from the remaining four ward sisters.The interventions were then quickly rolled out across these wards.Ward pharmacists were expected to provide all new, bank and agency nurses with policy summary cards and instructional briefings when these staff were encountered.

The fourth and final intervention involved ward pharmacists directly investigating each instance of an inappropriately missed dose at the time of its discovery. In these circumstances the pharmacist sought to speak directly to the nurse involved.This was treated as an educational intervention: informing the staff member about the nature of the breach of policy. An incident form was also completed. It is important to note that this did not impinge significantly upon the other ward- based activities undertaken by the pharmacists involved.

Results

Baseline data collection took place on five surgical wards (121 beds) for three months. Further data collection was undertaken for nine months after this, during the intervention phases. Data were collected daily, on Mondays to Fridays, by ward pharmacists. The baseline mean “missed dose” value was 13.3 per cent (SD 7.6 per cent). Following the first round of interventions the mean “missed dose” value fell to 4.8 per cent (SD 4.0 per cent) (see Figure 2).

Following full implementation of the final intervention the mean number of patients experiencing one or more missed doses fell to 1.4 per cent (SD 2.6 per cent).

Discussion

Before publication of the NPSA report on missed doses the issue was given relatively low priority by both pharmacy and nursing staff within our organisation. There was general awareness of it but no formal attempts had been undertaken to reduce the occurrence, nor had there been any attempt to quantify the extent to which it occurred. When the subset of missed dose data in the preoperative setting was reviewed, the 13.3 per cent incidence was immediately recognised as a genuine clinical concern.

Having identified our two main groups of causes of missed doses to be “unavailability” and “policy misinterpretation” (see Panel), the decision to run two separate projects was taken. Neither project attempted to focus on drugs that, when unintentionally missed, were more likely to result in adverse clinical events. Instead, the projects focused on trying to address all missed dose incidents by strengthening process and procedure and raising awareness of the dangers of missed doses.

The four interventions made had the effect of changing the behaviour of ward staff through education, and challenging deviation from policy through a combination of education and incident reporting, and was shown to be effective. The interventions themselves were neither complex to initiate nor needful of additional resources, relying primarily upon regular daily clinical pharmacy ward visits to maintain this performance.

Initially pharmacists had regarded such simple interventions as lacking the sophistication that they associated with ward- based clinical pharmacy work and would not result in any positive outcome. By the end of the project they were convinced that simple reliable interventions were easier to introduce and sustain in practice.

PDSA rapid cycle testing and Institute for Health Care Improvement change methodology[6]

ensured that the project progressed in a timely and organised manner. The data collection sample technique used is statistically valid[4]

and, with only five drug charts being reviewed each day, was not considered to be laborious. Maintaining these results has proved to be manageable. Surgical ward pharmacists continue to provide new, bank and agency nurses with the summary cards and two-minute instructional briefings. Minor changes to the perioperative policy have occurred since completion of the project. It was found that bedside notices were easy to update, as were summary cards to amend and reissue.

It is worth noting that during the course of the project a change occurred in nursing practice which is likely to have added to its success. This was the introduction of “nursing metrics”, one of which was aimed at reducing the incidence of undocumented reasons for omitting medicines, and the other to address blank MAR chart entries. These were reported monthly via run charts and showed a significant reduction in both measures. However, it is impossible to determine the magnitude of the contribution that this may have had.

Also, examination of Figure 2 shows that the falls in missed dose incidence correspond to the spread of interventions to all general surgical wards. This strongly suggests a causal link.

The main concern with this project is that it relies on regular input from ward pharmacists at ward level. It is conceivable that reductions in the frequency of clinical pharmacist ward visits might eventually result in a gradual increase in the incidence of missed doses. Ideally one would envisage an electronic prescribing/administration recording system being used to flag each instance of missed doses to the appropriate staff in real time. In the meantime manual interventions appear to have proven to be effective.

Finally, since the end of the project, data collection and reporting have been reduced from weekly to monthly to monitor for change. Following the success of the project across the initial five wards the intervention bundle has been introduced to the remaining five surgical wards.

Conclusion

Simple, systematic and timely interventions intended to increase the reliability of administration of medicines to surgical patients in the preoperative period were effective and sustainable. Additionally, there was minimal financial investment required to achieve this change. Neither was there any need significantly to modify existing policy or procedures.This intervention bundle could be easily adapted and implemented in any surgical ward where clinical pharmacist visits occur each day.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following people for their participation and contribution to the success of this project: ward managers Donna Ryan, Penny Gillcripps, Julie Smith, Cathy Phillips, Sharon Conway and their nursing teams; Richard Burgess, surgical pharmacist, for his assistance with the data collection and testing; Bernie wilcox for nurse-held summary card production; and the medical photography team for their assistance in producing bedside notices.

About the authors

David Chalkley, MPharm, DipClinPharm, is lead pharmacist for surgery and critical care) and Jon Beard, MSc, DipClinPharm, is chief pharmacist at Musgrove Park Hospital, Taunton & Somerset NHS Foundation Trust.

Correspondence to: Mr Chalkley (email david.chalkley@tst.nhs.uk).

References

[1] National Patient Safety Agency. Rapid response report 009. Reducing harm from omitted and delayed medicines in hospital. 2010. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa. nhs.uk (accessed 29 June 2011).

[2] Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Borwn KA et al. 2009 ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade, incorporated Into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009;120:e169–e276

[3] Ashley M. How can effective medicines reconciliation be achieved? Pharmacy Management 2010;26:3–7.

[4] Benneyan JC, Lloyd RC, Plsek PE. Statistical process control as a tool for research and health care improvement. Quality and Safety in Healthcare 2003;12:458–64.

[5] Deming WE. New economics for industry, government, education. Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study, 1993.

[6] The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Boston: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003.