Abstract

Aim

To describe the early development and uptake of local pharmaceutical services and to investigate the nature of the contracts developed by the first-wave pilots.

Design

Analysis of Department of Health data on 31 LPS pilots receiving ministerial approval by 1 October 2004 and content analysis of 10 first-wave LPS contracts.

Outcome measures

Uptake and characterisation of LPS pilot schemes. Contract analysis: typology of services, contract pricing, monitoring and review arrangements, staff standard and competencies.

Results

31 LPS pilots have been approved in three waves, involving 147 potential service providers concentrated in urban locations across England. To date, nearly half of the pilot schemes (15/31) have been implemented. LPS pilots fall into three main categories: extended community pharmacy services, specific community pharmacy services, and out-of-hours services. Dispensing is worth between 14 and 100% of the total LPS contract value; a variety of payment mechanisms reimburse contractors for LPS services. PCTs and LPS providers take joint responsibility for monitoring and review, the results of which may inform the future contract price. Staff competencies were not routinely addressed; instead contracts tended to focus on the continuing professional development requirements of staff.

Conclusions

LPS pilots are addressing a number of government priorities. Many LPS services will be mainstreamed in the new national contract, the development of which has slowed the growth of LPS. The use of LPS to enable the provision of innovative services has been demonstrated. In commissioning new community pharmacy services, the length of time taken to develop and implement services should be acknowledged.

The NHS (Primary Care) Act 1997 heralded the most recent period of change in contractual arrangements between commissioning bodies and primary care service providers.

Starting in 1998, the first new contracts were tested by the personal medical services (PMS) pilots for general practice and personal dental services (PDS) pilots for dentistry. In 2003 the base contract for general practice, the general medical services (nGMS) contract, was revised to incorporate and roll out many of the innovations developed under the PMS contract. The development of the general practice contracts has been mirrored in dentistry and community pharmacy (see Panel 1).

Panel 1: Primary care contract options

General practice

- Personal medical services( PMS), 1998

- General medical services (nGMS), 2003 — replacing the former general medical services contract (GMS)

Primary dental care

- Personal dental services (PDS), 1998

- General dental services (nGDS), 2005 — replacing the former general dental services contract (GDS)

Community pharmacy

- Local pharmaceutical services (LPS), 2002

- General pharmaceutical services (nGPS), 2005 — replacing the former general pharmaceutical services contract (GPS)

Until 2002, the general pharmaceutical services (GPS) contract was the only contract option available for contractors wishing to provide pharmaceutical services in the community. A second option, a local pharmaceutical services (LPS) contract, was first mooted in the NHS plan in 2000, and was rolled out as a pilot scheme in 2002. The aim of the LPS contract is “to demonstrate new ways in which to organise and pay for community pharmacy, to deliver a wider range of services than under the current national contract, enabling local needs to be met more effectively.”1 In line with the experiences of general practice, a new base contract, the new general pharmaceutical services (nGPS) contract, is now being negotiated for roll-out in 2005.

Changes in community pharmacy contracting have been necessary to acknowledge the work that contractors undertake beyond their dispensing role. Remuneration for a limited number of services, such as the provision of pharmaceutical advice to care homes, has been through local arrangements with health authorities and primary care trusts using a national tariff.2 In addition, contractors wishing to be remunerated for the provision of services beyond those outlined in the Drug Tariff would have to approach their local health authority and set up a separate financial arrangement, most commonly using a service level agreement. The creation of the professional allowance in 1993 was an acknowledgement within the GPS contract that community pharmacy contractors should be reimbursed for their work outside dispensing NHS prescriptions.3

In 2003, a survey of PCT commissioning activities in relation to community pharmacy services found that the top seven commissioned services were: needle and syringe exchange, supervised consumption of methadone, provision of pharmaceutical advice to care homes, medication review, smoking cessation, emergency hormonal contraception by patient group direction and compliance support.4 The survey also reported that the key services that PCTs aspired to commission were minor ailments schemes, medication review services and compliance support services. Community pharmacists are also being commissioned by PCTs to deliver services which meet the public health agenda.5 The LPS contract is being used as a tool to commission all of these types of services and is a test-bed for service design and costing.

In this paper, we aim to describe the early development and uptake of LPS. We will investigate the nature of the contracts developed by the first-wave pilots specifically considering the services being provided, service targets, contract value, payment mechanisms, monitoring and review procedures, dispensing arrangements and staff standards and competencies.

The paper will conclude with a discussion of these LPS characteristics, in the overall context of commissioning and in comparison with PMS and nGPS.

Methods

This study is part of a larger programme of research forming a national evaluation of LPS pilots. The evaluation is a two-year project, involving a series of interrelated studies of first-wave pilot sites. Results presented here are drawn from two data sources: information held by the Department of Health relating to all waves of the pilot scheme and an analysis of the first-wave LPS contracts.

DoH information

The LPS process requires PCTs to submit documentation or stattus forms at various stages of the LPS process.6 The information drawn from this data set includes:

- The name of the PCT submitting the proposal

- The type of proposal (preliminary or full)

- The wave the proposal was submitted in

- The date of submission of proposal

- The date of acceptance of proposal

- The date of implementation of service (ie, the date that the contracted LPS services were first provided)

- The number or proposed number of providers of the service

Contract analysis

All PCTs commissioning first-wave pilots were requested to forward a copy of their LPS contract to the evaluation team, once it was signed off by all parties involved. Two researchers worked independently to review the documents, using a purpose-designed data extraction form. The data extraction form was based on a similar tool used by the evaluation team for PMS. Categories used to build the data extraction form are given in Panel 2. Supplementary notes were taken where necessary to provide additional depth of information. Data were coded and entered into SPSS and Excel for analysis.

Panel 2: Contract analysis — data collection categories

- Signatories, duration of contract, start date, contract period

- Contract value and payment, scope and value of contract, set-up costs, incentive payments

- Dispensing element — all/targeted/specific dispensing, mechanisms for adjustments, premises, target population, dispensing hours, dispensing volume targets

- LPS service specification — payment schedule, frequency of payments, payment mechanisms, mechanisms for adjustments, nature of services, nature of premises, target population

- Monitoring and review, quality control, financial review dates

- Change control, sub-contracting, termination, right of return

- Dispute — disciplinary and industrial dispute resolution procedures, grievance procedures, complaints procedures

- Standards of service — health and safety, insurance and limitation of liability, information, confidentiality, security and data protection, duty to provide information

- Staff — staff standards, staff training and development, provider of training (pharmacist and other pharmacy staff)

Results

Development of the LPS pilot scheme

Uptake of LPS

Uptake of LPS has been limited to date. There have been three waves of LPS pilots. Eighteen first-wave (1A and 1B) pilots were agreed in 2002/03, comprising 10 preliminary proposals and eight full proposals. A further 12 pilots (10 preliminary, two full) were agreed in the second wave in 2003. Most recently, in the first round (3A) of the third wave in 2004 three new pilots were approved(two preliminary, one full); some pilots with preliminary approval in waves 1 and 2 were also granted full approval in this round. In order to provide accurate figures on actual numbers of pilots, each scheme has been counted in the wave in which it first applied for approval.

Number and type of providers

Across the three waves of pilots, there are 147 potential providers. In March 2003 there were 10,452 community pharmacies in England and Wales7; LPS is being used by 1.4 per cent of community pharmacy contractors. The 24 providers involved in waves 1A and 1B of LPS represent a cross-section of community pharmacy: nine multiples, nine small/ medium-sized chains and six independent contractors. There were also two other providers: one GP co-operative and one hospital pharmacy. There are three first-wave pilots which have not yet been implemented; these will involve a further 15 community pharmacies.

Distribution of LPS pilots

First-wave pilots were mainly located in urban areas (both inner city and town) with only one pilot operating in a rural location. There is distinct geographical clustering of the first-wave pilot locations, concentrated in three areas of England (the north-east, the north-west, and London and the south-east).

The second wave followed a similar pattern, with all but two pilots located within the same clusters.

The third wave appears to be independent of this early clustering.

Timescale for pilot development from submission to implementation

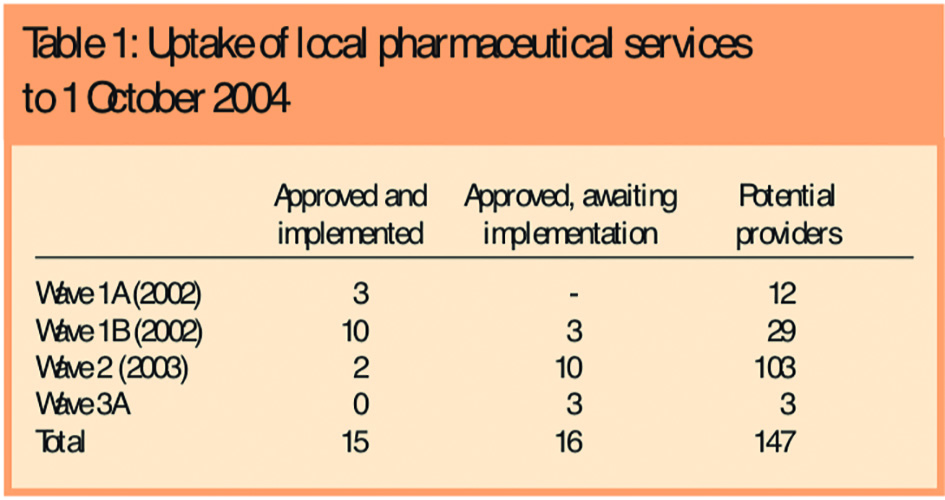

Across the three waves of LPS pilots approved to date, almost half (15/31) have been implemented (see Table 1).

The remaining pilots are expected to have been implemented by February 2005. Details from the first-wave pilots provide further information about the development time of the pilots from proposal to implementation. The wave 1A pilot proposals were submitted in June 2002 and approved in August 2002. The wave 1B pilot proposals were submitted in November 2002 and approved in December 2002. Two pilots were implemented on 1 March 2003, and a further five pilots were implemented in April 2003. The remaining pilots were implemented over the following months, the most recent in March 2004. There are three first-wave pilots still outstanding and awaiting implementation.

Contractual details of the first wave pilots

Number and style of contracts used in analysis

A deadline was set for receipt of the contracts by the evaluation team for 1 November 2003; at this “census point” 10 contracts were available for analysis. Each PCT had to construct its own contract. Seven of the contracts were in a similar format, comprising a legal “front end” and a service specification (supplying the bulk of the detail about the services to be provided). This style of the contract was influenced by the generic contract offered to contractors by the National Pharmaceutical Association, consultants, pharmacy legal specialists, guidance from the Pharmaceutical Services negotiating Committee, and the first contract drawn up in the NORTH WEST region by the Manchester pilot. Only three contracts used an alternative format, and these were considerably shorter than the more popular format, mainly consisting of a brief outline of the services to be provided.

Links with the GPS contract

LPS guidance states that LPS providers who were operating under the GPS contract before transferring to the LPS contract have the right to return to the GPS contract.8 Any new pharmacies created with an LPS contract do not have the right to return to a GPS contract because they did not hold one originally. If one of these pharmacies wished to switch contracts they would have to apply for a GPS contract under the normal control of entry regulations.

Two of the first-wave pilots have been set up to allow their providers to hold an LPS contract alongside their GPS contract. This arrangement allows the pharmacies to provide a service to a specified population and covers dispensing to this population, with all other dispensing and service provision remaining under the GPS contract.

Dispensing under LPS

An LPS contract includes a dispensing element, either for an identified population or for all NHS dispensing from a given pharmacy. The anticipated dispensing activity is based on historical activity, taking into account recent trends in activity at the pharmacy and any exceptional circumstances such as the relocation of the pharmacy.

Mechanisms for adjusting the dispensing payments at the end of each year were described in seven out of 10 of the contracts. All adjustment mechanisms were related to volume of prescriptions processed. For example, if the volume of prescription items dispensed either exceeds or falls short of the annual target by 2 per cent and the difference cannot be accounted for by LPS activity, then the PCT will adjust the contract value equivalent to the difference between the price of the dispensing element and the value that would have been paid under the GPS remuneration terms for the actual dispensing volume.

LPS services

Alongside dispensing services, the types of services being provided by first-wave LPS pharmacies can be categorised into three main groups: extended community pharmacy services, specific pharmacy services and out-of-hours services (Panel 3).

Panel 3: First-wave local pharmaceutical services

Extended community pharmacy services — pharmacies providing a wide range of additional services, including a selection of the following: smoking cessation service, provision of emergency hormonal contraception under a patient group direction, minor ailments services, medication review services, repeat dispensing, domiciliary services, provision of compliance devices, treatment of head lice, needle exchange schemes, supervised consumption of methadone.

Specific community pharmacy services — pharmacies focusing on the provision of one of the following services:

- Medication review services — these vary according to the location of the review, whether the pharmacist has access to GP records, and who refers into the service

- Care and support programme for substance misuse — working with social care drug action teams to provide services targeted at improving the health of drug misusers, including supervised consumption of methadone, diagnostic testing, needle exchange, vaccinations, management of overdose, extending general medical services through community pharmacies

- Training and development services — use of a community pharmacy that other pharmacists can attend to experience and receive training in the provision of new services in order to spread good practice within the primary care trust

Out-of-hours services — creation of a pharmacy within an out-of-hours primary care centre to dispense medicines and to develop the role of the pharmacist in providing advice to patients and other health care professionals

All of the contracts define the target population of the LPS services (Panel 4). Some services require referral from other health care practitioners to provide patients for the services. However, these other health care professionals are not signatories to the contracts, so have no contractual obligation to refer patients.

Panel 4: Defining the target population for local pharmaceutical services

- Clinical need — eg, people with a chronic disease, such as diabetes

- Demographic characteristics — eg, people over the age of 65 years

- NHS targets—eg, people aged 75 years or over taking four or more medicines

- Geographic characteristics — eg, the catchment area for a particular community pharmacy or an area in a regeneration programme

Analysis of the 10 first wave LPS contracts showed that seven contracts state volume targets for some, or all, of the LPS services, with remuneration directly linked to the targets. The most common adjustment used in the contracts for amending payments for LPS services is the reallocation of money to other LPS services within the same contract. For example, if the number of minor ailments consultations undertaken does not reach the stated target, then the money can be allocated to allow for more medication reviews to be funded. Two of the contracts do not state any targets and simply provide a brief outline of the requirements for the service.

Contract price

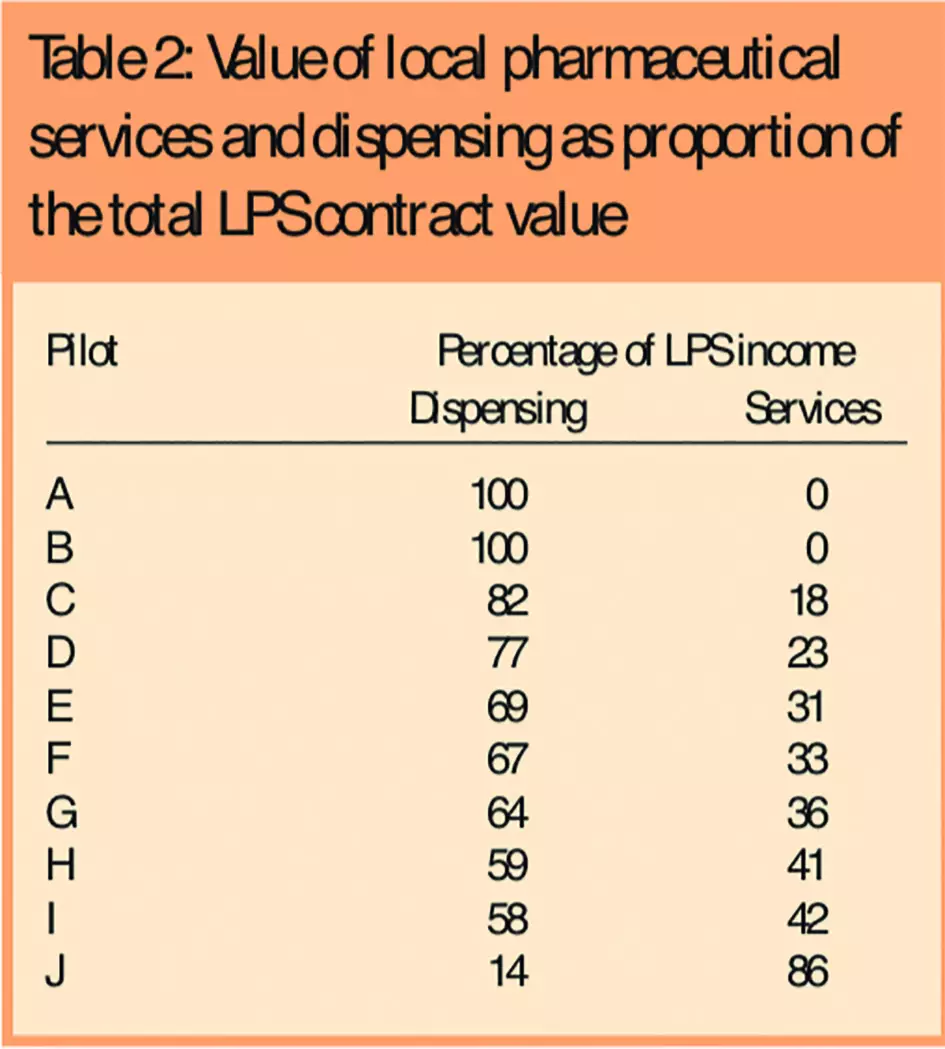

The value of the dispensing element and LPS services make up the total contract value. The proportion of each element varies across the first-wave contracts. Table 2 shows that the dispensing element of the contracts is worth between 14 and 100 per cent of the total contract value. The payments for LPS contracts can be paid by PCTs or through the PPA. Some PCTs have arranged to pay for services prospectively, and adjust for volume of service at the end of the year, while others link payment to volume and are paid in arrears.

The majority of the contracts used a “fee for service” payment mechanism for their LPS services, set against expected volume targets. Examples of fee for service include £1 per dose of supervised methadone, or £10,000 per annum to provide a fixed number of medication reviews. However, other payment mechanisms are also used within mixed/blended payment systems, including basic allowances, capitation fees and salary payments. One example of a mixed/blended payment systems is £300 (basic allowance) plus 70p per pack of needles distributed (fee for service) in a needle exchange scheme. A second example is £70 per medication review (fee for service) plus £5 per month per registered patient (capitation fee), limited to 300 patients per annum.

Monitoring and review

All contracts describe some monitoring and review procedures, in which the PCT and LPS providers take joint responsibility for monitoring. The contracts have little focus on monitoring dispensing services; more detail is provided for the monitoring of LPS services. Three review periods are mentioned in the contracts. Five of the contracts describe a “set-up period” review schedule, involving monthly reporting for the first three months of the LPS contract. Seven contracts describe a quarterly review schedule, reporting to the PCT or the PCT steering group. The possible actions resulting from the quarterly reviews are feedback and discussion with the LPS providers and adjustments made to payments. Four contracts also include an annual review, reporting to the PCT or a steering group, which may make adjustments to payments or consider impact on local community pharmacies, patients and staff, as a result of the review.

Eight of the contracts give details about how LPS payments will be adjusted according to the results of monitoring and review. Two contracts do not link monitoring and review to LPS payments. One contract states that adjustments to the LPS payments will be made following an annual review — additional detail on the nature of the adjustments or the content of the annual review are not given. Four contracts state that adjustments to LPS payments will result from monitoring and review processes where volume targets are not met.

Staff standards and competencies

The contracts were analysed to identify any staff standards required by the LPS services. One contract stated that the pharmacist and the technician must be skilled as necessary for the post — ie, related to competencies. On the whole, reference to staff standards was in the form of training and development requirements. For example, where a pharmacist intends to provide medicines advice to Care Homes, he or she must hold the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education certificate “Home away from home”.

Six contracts state that the responsibility for staff training and continuing professional development (CPD) lies with the LPS provider. However, the provider of the training and development may be the PCT or the LPS provider or it may be shared between the PCT and the LPS provider. Alternatively, it may be arranged through another provider, such as the CPPE. Of these six contracts, four refer to monitoring staff standards and competencies. Monitoring is undertaken by the PCT is all cases. PCTs have committed to obtaining written proof of training and qualifications where they have been explicitly required in the contract.

Discussion

Services commissioned under LPS have been developed to address a number of government priorities. The LPS pilots aim to improve access, enhance the provision of out-of-hours care, extend the roles of practitioners and meet some of the targets set in various national service frameworks. Provision of many of the LPS services will be mainstreamed in the nGPS contract9; some pilots providing such services may choose to exercise their right to return the GPS contract rather than continue with LPS.

Collecting and interpreting the LPS contracts was problematic for three reasons. First, some pilots implemented services before signing off their contracts, which resulted in delays in receiving the contracts from PCTs. Secondly, it is not a straightforward process to define what constitutes an LPS service. Some LPS contracts include services which may have previously been remunerated through the GPS contract or locally funded initiatives. Two contracts have labelled these types of services as core services and extended services. However, other contracts may include such services, but have chosen to refer to them as LPS services. Thirdly, creating a suitable data extraction form was difficult because of the variety in the style and content of the contracts. This variety was a result of the process of developing the contracts being devolved to PCTs and contractors to negotiate locally.

Parallels have been drawn between the development of PMS and nGMS with LPS and nGPS. However, unlike PMS, the proportion of contractors using the LPS contract is small. By the third wave of PMS 18 per cent of GPs were working under the new contract.10 By comparison, less than 1.4 per cent of community pharmacy contractors are using the LPS contract across the first three waves. However, LPS is evolving through the waves, with two PCTs in wave 2 rolling out the LPS contract across all community pharmacies within their areas. This wholesale adoption of the contract within a PCT more closely reflects the way that PCTs and GPs adopted the PMS contract.10 As with PMS, it is possible for non-traditional contractors to hold a contract. This contributes to the Government agenda of expanding and developing the NHS workforce.1

The development and implementation of the LPS contract has been hindered by two important factors. First, the poor uptake in wave 3 of LPS can probably be attributed to the impending release of the nGPS contract. Many contractors and PCTs have been unsure of the need to invest in commissioning services through LPS if the national contract will enable them to commission and provide similar services under a national framework. This situation differs to that of PMS which was running for five years before the introduction of nGMS. Secondly, uptake of services has been slow in many pilots owing to problems with referral of patients to the services. This may result from other health care professionals, upon whom the LPS pilots are reliant for patients, not being signatories to the contract which may impact on their commitment to the services.

The LPS contract was designed to encourage innovation. Evidence from the first-wave pilots suggests that there has been limited success towards this aim, many services being commissioned in the first wave are already being provided elsewhere under different commissioning arrangements. Rather, it has been used to provide security of funding for community pharmacy services. However, a small number of pilots have used the LPS contract to create unique, cutting-edge services. Similarly, although there is some variety in payment mechanisms used within the contracts, there has been little innovation in pricing and payment. Patterns of clustering of uptake are reasonably common in innovation.11 In LPS, the distribution of the pilots can, in part, be attributed to “champions” of LPS and community pharmacy pushing developments locally and stimulating local colleagues.

Experiences from the development of LPS provide useful information for future commissioners of community pharmacy services. New and innovative services take time to develop and may be impacted upon by other commissioning developments, within community pharmacy, and also across primary care. The LPS contract has been used to provide services which may, in the longer term, be more appropriately commissioned using nGPS. However, there are a number of LPS services that could only be commissioned using an LPS contract. The LPS contracts have attempted to define arrangements relating to monitoring and review and staff training and competencies, both of which are important topics for commissioners of community pharmacy services. Local negotiations have resulted in variety across the LPS contracts; those PCTs involved in LPS will have learnt valuable lessons which will be transferable to future community pharmacy commissioning.

About the authors

Juliette Kendall, MSc, is research fellow, Darren Ashcroft, PhD, MRPharmS, is clinical senior lecturer, Fay Bradley, MA, and Rebecca Elvey, MA, are research associates, Karen Hassell, PhD, is NHS career scientist/senior research fellow, and Peter Noyce, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of pharmacy practice at the Manchester school of pharmacy. Bonnie Sibbald, PhD, is professor of health services research and deputy director of the National Primary Care Research and Development Group

Correspondence to: Juliette Kendall, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL (e-mail juliette. kendall@manchester.ac.uk

References

- Department of Health. The NHS Plan: A plan for investment. A plan for reform. London: The Stationery Office;2000.

- Department of Health and National Assembly for Wales. Drug Tariff. November 2004. London: The Stationery Office; 2004.

- Huttin C. A critical review of the remuneration systems for pharmacists. Health Policy 1996;36:53–68.

- Celino G. Commissioning additional services. What is driving community pharmacy development? Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee Conference 2003. Available at: www.psnc.org.uk

- Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A. Community pharmacy’s contribution to improving public health: learning from local initiatives. Pharmaceutical Journal 2003;271:623–5.

- Department of Health. Local pharmaceutical services. Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/PolicyAndGuidance/ MedicinesPharmacyandIndustry

- Department of Health. General pharmaceutical services in England and Wales 1993–94 to 2002–03. London: The Stationery Office; 2004.

- Department of Health. Local pharmaceutical services (LPS). guidance notes. Third wave (2004) applications. London: Department of Health; 2004.

- NHS Confederation. The new community pharmacy framework. Issue 1, September 2004. London: NHS Confederation; 2004.

- Department of Health. Nearly a fifth of GPs in PMS (press release 2001/0549). Available at: www.dh.gov.uk/ PublicationsAndStatistics/PressReleases

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations (5th edition). New York: Free Press; 2004.

You may also be interested in

NHS England’s contract with Capita was a ‘shambles’ says Public Accounts Committee

Commissioning services and the new community pharmacy contract: (2) Drivers, barriers and approaches to commissioning