Abstract

Aim

To identify factors which primary care trusts consider to be barriers and drivers to the commissioning of services from community pharmacies.

Design

A self-completed questionnaire

Subjects and setting

All PCTs in England

Results

The response rate was 74%. 82% of PCTs reported access to funding to be a barrier to commissioning pharmacy services. Lack of PCT capacity was viewed as a barrier by 59% of PCTs and 53% viewed the impending PCT reconfiguration as a barrier. The main driver to commissioning was reported to be the new pharmacy contract (76%). Relationships between PCTs and local pharmaceutical committees (LPCs) were also viewed positively. The most common approach to commissioning adopted by PCTs was to engage proactively with LPCs and/or local pharmacists (92%). Most PCTs collaborated on the commissioning of pharmacy services with neighbouring PCTs (75%).

Conclusion

Collaboration across PCTs was found to be widespread which may be indicative of the need to address a lack of capacity. PCT reconfiguration also aims to address capacity issues, however this was viewed as a large barrier to commissioning by the respondents and future research will be needed to examine the impact this has on commissioning of community pharmacy services.

Since 2002 the commissioning of health services has been a core responsibility of primary care trusts.1 The commissioning role of PCTs has since been reinforced with the introduction of new primary care contracts in medical services, dentistry and pharmacy. Woodin describes commissioning as “a proactive strategic role in planning, designing and implementing the range of services required, rather than a more passive purchasing role. A commissioner decides which services or health care interventions should be provided, who should provide them and how they should be paid for and may work closely with the provider in implementing changes.”2

Commissioning is often described as a cycle — planning, contracting (or purchasing), monitoring and revising.3,4 The first paper in this series examined a crucial part of the planning stage — the use of pharmaceutical needs assessments.5 This paper is again located in the planning stage of commissioning and focuses on the way in which PCTs approach the commissioning of pharmaceutical services.

Previous research has suggested that a number of obstacles have inhibited the commissioning role of PCTs, such as lack of capacity, staff recruitment and retention problems.6 Evidence from previous research examining the commissioning of pharmacy services by PCTs suggests that the limited allocation of resources to pharmacy is a large barrier for PCT pharmacy teams.7,8 This paper aims to identify the factors that PCTs consider to be barriers to the commissioning of pharmaceutical services and also examines the factors that are considered to be drivers.

Methods

A pre-piloted questionnaire was distributed to all PCTs in England in March 2006 (n=290). A detailed description of the research method, sample and the topics covered by this questionnaire are provided in the first paper in this series.5

The questionnaire included attitudinal statements about approaches to commissioning community pharmacy services, which respondents were asked to rate their level of agreement on a five-point scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5). Respondents were also presented with a number of potential drivers and barriers to commissioning community pharmacy services and asked to rate these on a five-point scale from major driver (1) to major barrier (5). Both the attitudinal statements and driver/barrier categories were developed following a literature review9 and using knowledge gained through interviews with PCT pharmaceutical and commissioning leads for the national evaluation of LPS pilots.

Data were entered into SPSS v13.0 for analysis and frequency counts were performed. The net difference between responses was calculated. This represents the balance of opinion on attitudinal questions and has been calculated by subtracting the percentage of respondents in agreement with a statement or rating a factor as a driver from the percentage in disagreement with a statement or rating a factor as a barrier. For example, for drivers and barriers, the highest positive net difference demonstrate that a large proportion of PCTs consider these factors to be drivers, with only a small proportion considering these to be barriers. The lowest negative figures, therefore, represent the opposite and these can be considered the largest barriers to commissioning.

Respondents were also given the opportunity to add any additional comments at the end of the questionnaire. Free-text comments were read independently by two researchers and emerging themes were identified. Quotations are included in this paper to provide further insight into PCT staff views on commissioning pharmacy services.

Results

Responses were received from 216 PCTs, a response rate of 74%.

Drivers and barriers to commissioning

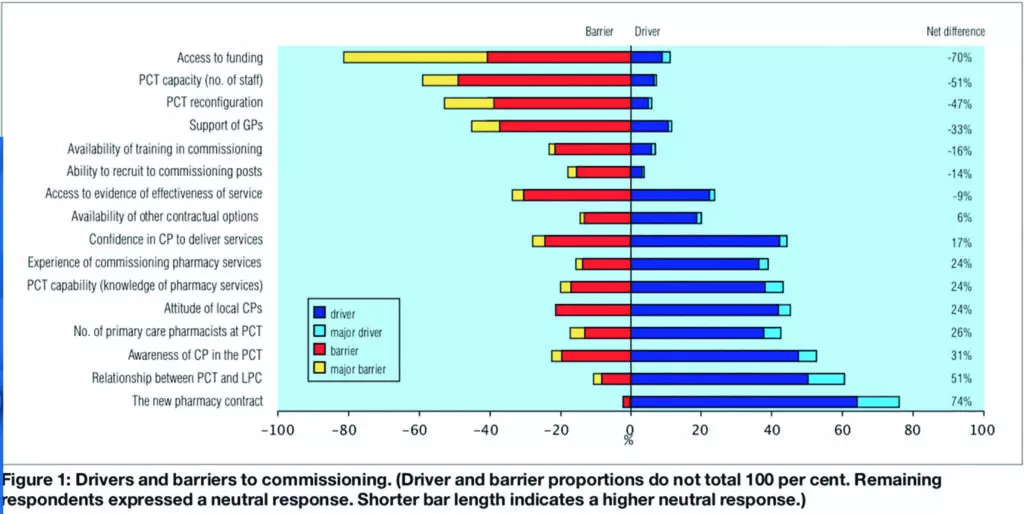

Figure 1 shows the proportion of respondents describing the factors listed as drivers and barriers to commissioning.

The main barrier to commissioning was reported to be access to funding. One hundred and seventy-six PCTs (82 per cent) reported this as a barrier with 89 of these (41 per cent) stating that this was a major barrier to commissioning. One hundred and twenty-five PCTs (59 per cent) believed that PCT capacity (in terms of the number of staff) was a barrier; 22 of these PCTs (10 per cent) thought this was a major barrier. The impending PCT reconfiguration was also viewed as a barrier to commissioning by 113 PCTs (53 per cent), 30 of which (14 per cent) described this as a major barrier. Support from GPs was also viewed to be a barrier by 97 PCTs (45 per cent).

The main driver to commissioning was reported to be the new pharmacy contract. One hundred and sixty-four PCTs (76 per cent) described the new contract as a driver, with 26 of these (12 per cent) stating that it was a major driver to commissioning. Relationships between PCTs and local pharmaceutical committees (LPCs) were viewed positively by 131 PCTs (61 per cent), and 23 of these (11 per cent) viewed this as a major driver. Awareness of community pharmacy at the PCT was described as a driver by 114 PCTs (53 per cent).

Free text comments given by the respondents to the questionnaire further support these findings and offer greater insight into the complexity of commissioning community pharmacy services. Financial constraints at PCTs were the most common problems mentioned by respondents:

At a time when PCTs are under financial pressure, developing community pharmacy is difficult — there is a will but little resources. (PCT 111)

Huge problems finding resources to commission new services in current financial climate — not allowed to spend anything or develop services. (PCT 108)

Other respondents commented that even though funding was available, pharmacy was often overlooked by PCTs during the allocation of this funding and often disregarded in favour of GPs when making commissioning decisions:

Lack of funding ear-marked for pharmacy has been a major barrier in taking forward new pharmacy enhanced services. (PCT 033)

PCT doesn’t regard the pharmacy contract as a high priority — GPs are primary care, no other contractor matters. (PCT 184)

Other respondents expressed problems in relation to recruitment and capacity for commissioning in PCTs. The impending reconfiguration of PCTs was also mentioned as a barrier and a distraction from the commissioning of pharmacy services:

Lack of capacity in medicines management team to meet demands of expanding role and huge medicines management agenda. (PCT 083)

We’ve been trying to develop services against a background of proposed merger with neighbouring PCTs and frozen recruitment since summer 2005. (PCT 003)

The sheer volume and range of changes within primary care, including NHS reconfiguration, has significantly diverted attention. (PCT 159)

Some respondents were also critical of community pharmacists for not being more proactive in developing service ideas:

The development of pharmacy services is largely undermined by the lack of drive among community pharmacists to develop and deliver services. (PCT 098)

There appears to be insufficient enthusiasm among community pharmacists to put forward any business proposals. (PCT 087)

Approaches to commissioning

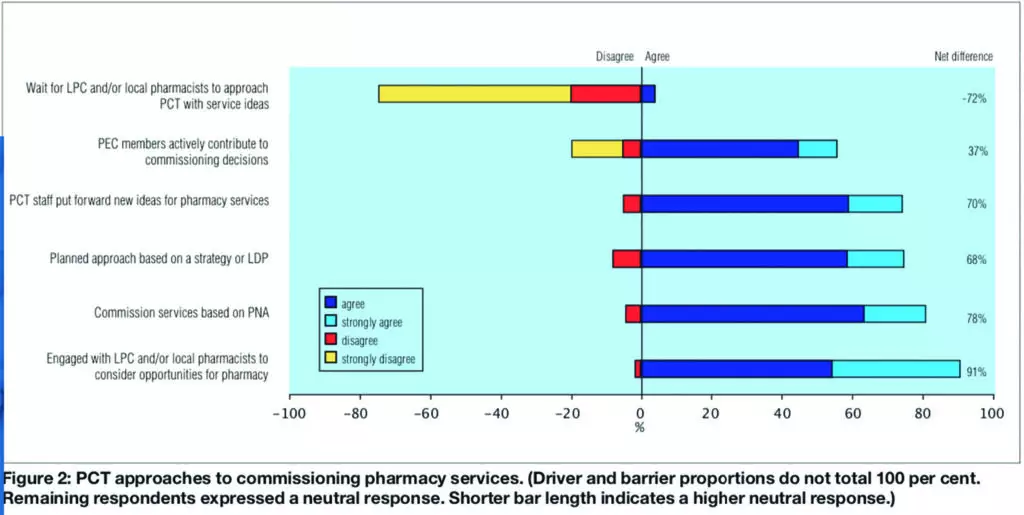

One hundred and ninety-eight PCTs (92 per cent) proactively engaged with LPCs and/or local pharmacists to consider service opportunities for pharmacy; 80 of these (37 per cent) agreed strongly with this statement (see Figure 2).

This also corresponds with the finding that the relationship between PCTs and LPCs is an important driver to commissioning. One hundred and seventy-six PCTs (82 per cent) stated that their approach was to commission services based on their pharmaceutical needs assessments (PNAs). One hundred and sixty-two PCTs (75 per cent) stated that they adopted a planned approach to commissioning based on a strategy or local delivery plan (LDP) and the same figure stated that PCT staff put forward new ideas for pharmacy services. The contribution of professional executive committee (PEC) members to the commissioning process varied across PCTs, with 121 PCTs (57 per cent) agreeing that PEC members actively contribute to commissioning decisions on community pharmacy services.

One hundred and sixty-four PCTs (77 per cent) disagreed that they waited for the LPC or other pharmacists to approach them with service ideas, with 43 of those (20 per cent) saying they strongly disagreed. This indicates that, although PCTs may collaborate with the LPC and local pharmacists in their commissioning approach, PCTs believed that, on the whole, they are the instigators of this process.

Joint commissioning of community pharmacy services with neighbouring PCTs was found to be widespread, with 161 PCTs (75 per cent) stating that they did collaborate on the commissioning of services from community pharmacies with one or more other PCTs.

Discussion

This survey has identified that the main barriers to commissioning pharmaceutical services for PCTs are access to funding, PCT reconfiguration, PCT capacity and GP support. Previous research evaluating the local pharmaceutical services (LPS) contract also found that these were major barriers to commissioning services from community pharmacy, with the exception of PCT reconfiguration, which was not on the agenda at the time. A recurring theme emerging from interviews with PCT leads for the national evaluation of LPS were the problems they had experienced when trying to secure funding for pharmaceutical services. Lack of PCT capacity was also a common theme and interviewees often spoke of their increasing workload and consequent shortage of time.10 These issues appear to be equally important in commissioning community pharmacy services as part of the new contractual framework.

The ability to recruit PCT staff was identified as more of a barrier than a driver by this survey, as was the availability of training in commissioning. Conversely, however, experience of commissioning and knowledge of pharmacy services were viewed as drivers rather than barriers by the survey respondents. Again the national evaluation of LPS also identified problems with the recruitment and retention of PCT staff. This lack of continuity consequently impacted on the relationship between the commissioner and the provider.

Previous survey work conducted before the introduction of the new pharmacy contract also suggested that access to funding was likely to be a key barrier and the relationship between the LPC and PCT was a main driver.9 However, a comparison between the results from this earlier survey and our own demonstrates that the new pharmacy contract is viewed as a greater driver now than it was in 2003 (a shift from just under 50 per cent viewing this as a driver to over 75 per cent). This is unsurprising given that in 2003 little was known about the format of the new contract, although it indicates that PCTs on the whole are positive about the contribution the new pharmacy contract could have on community pharmacy development. Other differences include support from GPs, which was viewed as a driver by 40 per cent in the earlier survey compared with only 12 per cent in these more recent figures. This may suggest GP support for the commissioning of services from community pharmacy has waned over the past few years or that GP support for community pharmacy is becoming increasingly more important for the development of community pharmacy services.

A lack of GP engagement is often cited as a major barrier to the uptake of community pharmacy extended services, particularly when services which rely on GP referral have low uptake rates.11,12 Increasing GP involvement in the commissioning process could improve the situation and help further the integration of community pharmacy into primary care, which the enhanced tier of the new pharmacy contract is designed to support, as well as benefiting GPs themselves.

One of the most important drivers to commissioning apart from the new pharmacy contract was reported to be the relationship between the PCT and LPC. However, PCTs were more likely to engage proactively with LPCs rather than wait for LPCs or local pharmacists to approach them. Previous research suggests that clinician engagement and involvement is critical to effective commissioning13 and it appears that with LPCs many PCTs have found an appropriate channel through which to do this. Nonetheless, some of the free-text comments from respondents also expressed frustration at the lack of ideas and enthusiasm shown by some community pharmacists. This could indicate that there is some ambivalence among both PCTs and community pharmacists as to who should generate new service ideas.

Although our survey focused primarily on commissioning pharmacy services, parallels can be seen across primary care commissioning as a whole. For example, from their three-year tracker survey of primary care organisations, Wilkin et al identify the main barriers to successful commissioning in primary care as having too many competing priorities, lack of funds, shortage of staff, and lack of influence over providers.14 From a review of the research evidence, Smith and Goodwin also identify lack of capacity for commissioning as a major issue to be addressed along with the recruitment and retention of staff and further development of specialist skills for commissioners.6 It appears, therefore, that the barriers identified in our survey are not necessarily confined solely to pharmacy commissioning.

As PCT capacity was identified by the survey as a barrier to commissioning, it is perhaps not surprising that the large majority of PCTs had developed joint commissioning with other local PCTs. Previous literature indicates that working with neighbouring PCTs is important if PCTs are to commission effectively over large populations.15 Wilkin et al’s PCT tracker survey also found commissioning with neighbouring PCTs to be widespread.14

The impending reconfiguration of PCTs is often cited as a means of addressing the lack of capacity PCTs have for commissioning and the extent of joint PCT commissioning that is already taken place may strengthen this argument. However, the respondents to our survey viewed PCT reconfiguration as the third most important barrier to commissioning — this may simply be due to the unknown, but also as a result of experience of previous reconfigurations and the time it takes to make these organisational changes. Wade et al argue that the successive reorganisation of commissioning bodies since they were first introduced has disrupted the development of commissioning as a profession or corporate function in the NHS.16 Future work will be needed to examine how PCT reconfiguration impacts on the commissioning of pharmacy services.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues in PCTs who put significant effort into providing us with a huge amount of detailed data during a period of considerable turbulence. This study was funded by the Department of Health.

This paper was accepted for publication on 24 July 2006.

About the authors

Fay Bradley, MA (Econ), and Rebecca Elvey, MA (Econ), are research associates, Darren Ashcroft, PhD, MRPharmS, is director of the Centre for Innovation in Practice and Peter Noyce, PhD, FRPharmS, is professor of pharmacy practice at the University of Manchester.

Correspondence to: Fay Bradley, Centre for Innovation in Practice, The Workforce Academy, School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL (e-mail fay.bradley@manchester. ac.uk).

References

- Department of Health. Shifting the balance of power withinthe NHS — securing delivery. London: The Department;2002.

- Woodin J. Health care commissioning and contracting. In:Walshe K, Smith J (editors). Healthcare management.Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2006.

- National Pharmacy Association. Commissioning resourcepack. St Albans: NPA; 2005.

- Bramley-Harker E, Lewis D. Commissioning in the NHS:challenges and opportunities. London: NERA Economic Consulting; 2005.

- ElveyR,BradleyF,AshcroftDandNoyceP.Commissioning services and the new community pharmacy contract: (1) Pharmaceutical needs assessments and uptake of new pharmacy contracts. Pharmaceutical Journal 2006;277:161–3.

- Smith J, Goodwin N. Developing effective commissioning by primary care trusts: lessons from the research evidence. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 2002.

- Kendall J, Elvey R, Bradley F, Ashcroft D, Hassell K, Sibbald B et al. National evaluation of local pharmaceutical services (LPS) pilots. Final Report (Vols 1&2). Manchester: University of Manchester; 2006.

- Bradley F, Ashcroft D, Elvey R, Noyce P. National evaluation of local pharmaceutical services (LPS) pilots. Final report on 2nd and 3rd wave pilots. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2006.

- Celino G. Commissioning additional services. What is driving community pharmacy development? Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee Conference 2003. Available at: www.psnc.org.uk (accessed 28 July 2006).

- Elvey R, Ashcroft D, Bradley F, Hassell K, Kendall J, Sibbald B et al. Setting up local pharmaceutical services – lessons for primary care trusts. Pharmaceutical Journal 2005;274:546–8.

- Bradley F, Kendall J, Ashcroft D, Elvey R, Hassell K, Sibbald B et al. Setting up local pharmaceutical services — lessons for pharmacy contractors. Pharmaceutical Journal 2005;274:548–51.

- ElveyR,AshcroftD,NoyceP. Repeatdispensing:thebenefits for GPs, pharmacists and patients. Prescriber;(19 June 2006):12–18.

- Audit Commission. The PCG agenda: early progress of primary care groups in England. London: The Commission; 2000.

- Wilkin D, Coleman A, Dowling B, Smith K. National tracker survey of primary care groups and trusts 2001/2002: taking responsibility? Manchester: University of Manchester;2002.

- Regan E, Smith J, Goodwin N, McLeod H, Shapiro J. Passing on the baton: final report of a national evaluation of primary care groups and trusts. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 2001.

- Wade E, Smith J, Peck E, Freeman T. Commissioning in the reformed NHS: policy into practice. Birmingham: University of Birmingham; 2006.