Key points

- Inhalers should be prescribed by brand.

- Fixed-dose combination inhalers offer advantages to patients by simplifying complex inhaler regimens.

- Dual long-acting bronchodilator (long-acting beta2 agonist [LABA]/long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA]) inhalers achieve clinical and statistically greater improvements in lung function and patient outcomes than placebo, and smaller but important improvements compared with long-acting bronchodilator inhaler monotherapy.

- LABA/LAMA inhalers may prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations to a greater extent than inhaled corticosteroid (ICS)/LABA inhalers, without the risk of pneumonia from inhaled corticosteroids.

- Triple-combination inhalers (ICS/LABA/LAMA) achieve incrementally greater reduction in exacerbation rates compared with LABA/LAMA inhalers.

- As there is no difference in cost or safety between UK-licensed combination inhalers within each class, the choice of which inhaler to prescribe should be based on the patient’s preferences.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a major cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide. Currently, it is the fourth leading cause of death globally, but owing to increased exposure to risk factors and an increasingly ageing population, it is predicted to become the third leading cause of death by 2020[1]

.

COPD is characterised by persistent breathlessness, sputum production and/or cough, owing to airflow limitation that does not generally vary from day to day. It is a preventable disease, mainly caused by tobacco smoking, but can also be a result of occupational exposure or exposure to biomass fuel and air pollution[1]

. Limited therapies are available to reduce mortality, although there have been advances in therapy to help relieve symptoms and prevent exacerbations.

This disease is thought to have been diagnosed in around 1.2 million people in the UK; however, it is believed that around 2 million more people are as yet undiagnosed. People from a lower socio-economic status are more likely to be diagnosed with COPD, but its overall prevalence is increasing too. It is not clear whether this is because it is becoming more common or whether it is being diagnosed more accurately[2]

.

Along with lung cancer and pneumonia, COPD is one of the three leading contributors to respiratory mortality in developed countries such as the UK[2]

. A total of 29,776 people died from COPD in 2012, accounting for 5.3% of the total number of UK deaths and 26.1% of deaths from lung disease[2]

.

Exacerbations contribute significantly to morbidity in COPD, with a greater exacerbation frequency associated with increasing severity of disease[3]

. COPD causes 115,000 emergency admissions and 24,000 deaths per year, and 16,000 deaths within 90 days of admission in England[4]

. In recent years, fixed-dose combination (FDC) inhalers containing dual long-acting bronchodilators (a long-acting beta2 agonist [LABA] plus a long-acting muscarinic antagonist [LAMA]), and triple FDC inhalers containing an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) plus LABA and LAMA, have been launched in the UK for the treatment of stable COPD.

This article reviews and summarises the evidence base on the safety and efficacy of LABA/LAMA and ICS/LABA/LAMA combination inhalers for the treatment of stable COPD, and describes their place in therapy.

Sources and selection criteria

Methods

To identify relevant English language publications for inclusion in this review, the authors performed a search of the online databases Medline and Embase up until May 2018 using the combination of search terms: “drug therapy, combination AND adrenergic beta-agonists AND muscarinic antagonists AND pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive”, and “drug therapy, combination AND adrenergic beta-agonists AND muscarinic antagonists AND inhaled corticosteroids AND pulmonary disease, chronic obstructive”. Publications were limited to human clinical trials of inhaled preparations currently licensed for use in the UK. Hand-searching of references in published studies was also used to identify additional studies that had not already been identified.

Studies were excluded where the studied inhaled preparation was not licensed in the UK, where the study compared an FDC inhaler with the same drugs given together but in separate inhalers, where studies assessed safety alone rather than efficacy, and cost-effectiveness analyses.

Results

A total of 355 publications were identified in the first search and 86 publications in the second search. After review of titles and abstracts, 22 and 5 published clinical trials were identified from each respective search and were selected for inclusion in this review. Reasons for exclusion of manuscripts included: papers not being clinical trials (review articles, cost-effectiveness studies or letters to editors); having an alternative indication to COPD; and having the wrong treatments or outcome under investigation.

Guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the management of COPD were last updated in 2010[5]

, and recommend an individualised approach to the sequence of inhaled therapies depending on factors such as lung function, symptoms, activities of daily living, exercise capacity and patient preference. It notes that:

- Short-acting bronchodilators (usually a short-acting beta2 agonist [SABA]) should be the initial therapy for all people with COPD, for the relief of breathlessness and exercise limitation;

- People with mild-to-moderate airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] ≥50% predicted) and persistent symptoms or exacerbations should be offered a long-acting bronchodilator (either of a LABA or a LAMA). If patients continue to experience persistent exacerbations or breathlessness despite monotherapy, they should be offered either an ICS with LABA (ICS/LABA) in a FDC inhaler, or a LAMA in addition to LABA where an ICS is declined or not tolerated;

- People with severe-to-very-severe airflow obstruction (FEV1 <50% predicted) should be offered an ICS/LABA in a FDC inhaler in addition to a LAMA[5]

.

However, these guidelines are now almost eight years old, and although a substantial update to the treatment recommendations is expected in December 2018[6]

, current guidelines predate published research on the safety and efficacy of FDC inhalers containing dual bronchodilators (LABA/LAMA) and triple-combination inhalers (ICS/LABA/LAMA). Consequently, many UK specialists and healthcare professionals refer to COPD guidelines developed by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) to make evidence-based treatment decisions[1]

. The GOLD guidelines utilise a combined assessment of symptoms and exacerbation history to categorise COPD patients into four clinical phenotypes (GOLD categories A, B, C and D), and recommend treatment according to phenotype:

- Category A (low symptoms, non-frequent exacerbators): short-acting or long-acting bronchodilator;

- Category B (high symptoms, non-frequent exacerbators): initially a long-acting bronchodilator (either a LABA or a LAMA), or combination of a LABA and a LAMA if there are persistent symptoms on monotherapy;

- Category C (low symptoms, frequent exacerbators): initially a LAMA as monotherapy; if exacerbations persist a LABA/LAMA inhaler or an ICS/LABA inhaler should be used, although LABA/LAMA is preferred owing to the increased risk of pneumonia with ICS use;

- Category D (high symptoms, frequent exacerbators): initially a LABA/LAMA inhaler, although an ICS/LABA inhaler may be preferred where there may be a history of asthma/COPD overlap, and/or a high eosinophil count (although this factor is still a matter of debate). If exacerbations persist in patients on LABA/LAMA, an ICS should be added. Further options may include the addition of a macrolide (currently unlicensed for this indication in the UK) or roflumilast[1]

.

The NICE and GOLD guidelines offer differing recommendations on the management of COPD, which may result in differing treatment pathways in different regions, and different decisions as to the place in therapy of FDC inhalers containing ICS/LABA, LABA/LAMA, or ICS/LABA/LAMA.

Inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting beta2 agonists

At the time of writing, there are currently 14 ICS/LABA inhalers licensed for the management of COPD in the UK[7]

(see Table).

The pivotal studies for ICS/LABA brands of Seretide® (GSK, Middlesex, UK), Symbicort® (AstraZeneca, Bedfordshire, UK), Fostair® (Chiesi Limited, Manchester, UK) and Relvar® (GSK) demonstrate significant improvements in lung function and health status compared with placebo, ICS or LABA monotherapy[8],[9],[10],[11],[12]

. Furthermore, in these studies ICS/LABA FDC inhalers were shown to significantly reduce the rate of COPD exacerbations compared with placebo, ICS or LABA monotherapy[8],[9],[10],[11],[12]

.

Generic ICS/LABA inhalers, such as Aerivio® Spriomax® (Teva UK Ltd, West Yorkshire, UK)[13]

, AirFluSal® Forspiro® (Novartis, Surrey, UK)[14]

, DuoResp® Spiromax (Teva UK Ltd)[15]

and Fobumix Easyhaler® (Orion Pharma UK Ltd, Berkshire, UK)[16]

, have received a licence as hybrid medicinal products after demonstrating equivalent dose delivery to the equivalent brand leader. They would be expected to achieve similar benefits for patients, provided that patients are taught how to use the inhaler device correctly and have demonstrated correct inhaler technique.

| Drug class | Generic name | Brand name | Manufacturer | Device | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPI: dry powder inhaler; ICS: inhaled corticosteroid; LABA: long-acting beta2 agonist; LAMA: long-acting muscarinic antagonist; pMDI: metered dose inhaler. | |||||

| LABA/LAMA | Umeclidinium/vilanterol | Anoro® Ellipta® 55 micrograms/22 micrograms | GSK, Middlesex, UK | DPI | One dose once daily |

| Formoterol/aclidinium | Duaklir® Genuair® 340 micrograms/12 micrograms | AstraZeneca, Bedfordshire, UK | DPI | One dose once daily | |

| Olodaterol/tiotropium | Spiolto® Respimat® 2.5 micrograms/2.5 micrograms | Boehringer Ingelheim, Berkshire, UK | Soft mist inhaler | Two puffs once daily | |

| Indacaterol/glycopyrronium | Ultibro® Breezhaler® 85 micrograms/43 micrograms | Novartis, Surrey, UK | DPI | One dose once daily | |

| ICS/LABA | Beclometasone dipropionate/formoterol | Fostair® pMDI 100 micrograms/6 micrograms | Chiesi Limited, Manchester, UK | Aerosol | Two puffs twice daily |

| Fostair NEXThaler® 100 micrograms/6 micrograms | Chiesi Limited, Manchester, UK | DPI | Two puffs twice daily | ||

| Budesonide/formoterol | DuoResp® Spiromax® 160/4.5 micrograms; 320/9 micrograms | Teva UK Limited, West Yorkshire, UK | DPI | 320/9 micrograms twice daily | |

| Fobumix Easyhaler® 160/4.5 micrograms; 320/9 micrograms | Orion Pharma UK Ltd, Berkshire, UK | DPI | 320/9 micrograms twice daily | ||

| Symbicort® pMDI 200/6 micrograms | AstraZeneca, Bedfordshire, UK | Aerosol | Two puffs twice daily | ||

| Symbicort Turbohaler® 200/6 micrograms; 400/12 micrograms | AstraZeneca, Bedfordshire, UK | DPI | 400/12 micrograms twice daily | ||

| Fluticasone furoate/vilanterol | Relvar® Ellipta 92/22 micrograms | GSK, Middlesex, UK | DPI | One dose once daily | |

| Fluticasone propionate/salmeterol | Aerivo® Spiromax 500/50 micrograms | Teva UK Limited, West Yorkshire, UK | DPI | One dose twice daily | |

| AirFluSal® Forspiro® 500/50 micrograms | Novartis, Surrey, UK | DPI | One dose twice daily | ||

| Fusacomb Easyhaler 500/50 micrograms | Orion Pharma UK Ltd, Berkshire, UK | DPI | One dose twice daily | ||

| Seretide® Accuhaler® 500/50 micrograms | GSK, Middlesex, UK | DPI | One dose twice daily | ||

| ICS/LABA/LAMA | Fluticasone furoate/ umeclidinium/vilanterol | Trelegy® Ellipta 92 micrograms/55 micrograms/22 micrograms | GSK, Middlesex, UK | DPI | One dose once daily |

| Beclometasone dipropionate/formoterol/ glycopyrronium | Trimbow® 87 micrograms/5 micrograms/9 micrograms | Chiesi Limited, Manchester, UK | Aerosol | Two puffs twice daily | |

Dual bronchodilators

There are currently four LABA/LAMA FDC inhalers licensed for the treatment of COPD in the UK[7]

(see Table).

Clinical trials have demonstrated that LABA/LAMA inhalers produce similar improvements in lung function compared with placebo, with improvements in trough FEV1 exceeding 100mL, which is generally regarded to represent a clinically important improvement in lung function[17],[18],[19],[20],[21]

. These studies also demonstrated smaller but significant improvements in lung function when compared with either LABA or LAMA single therapy, which were below this 100mL minimum clinically important difference in FEV1[17],[18],[19],[20],[21],[22],[23]

. However, this value is generally considered to relate to comparisons with placebo and it is not clear what the minimum clinically important increase should be when compared with bronchodilator monotherapy. These improvements in lung function appear to be significantly better for Spiolto® (Boehringer Ingelheim, Berkshire, UK) than placebo and numerically better than monotherapy independent of patients’ GOLD combined assessment category A, B, C or D[24]

, suggesting that COPD patients of all severities may benefit similarly from LABA/LAMA.

Important considerations in addition to improvements in lung function include the effect on patient-reported outcomes, such as breathlessness, quality of life and exacerbations that influences a patient’s perception of how COPD impacts on their life. The initial clinical studies were designed to have lung function as the primary endpoint as a regulatory requirement, so were often not designed or powered to demonstrate significant effects on these outcomes. In addition, 20–75% of patients were taking ICS at screening and throughout these studies, and 20–33% demonstrated significant reversibility to SABA/short-acting muscarinic antagonists, suggesting a degree of reversible airway disease and/or asthma, which may confound some of the outcome data.

With this caveat, improvements in health status with LABA/LAMA inhalers compared with placebo were similar for Anoro® (GSK), Duaklir® (AstraZeneca), Spiolto and Ultibro® (Novartis), although only Anoro and Ultibro were statistically significant; in some studies, Anoro, Duaklir and Spiolto demonstrated a clinically important fall of more than four units in the St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) score compared with placebo. Improvements in health status were small when compared with either LABA or LAMA monotherapy, and often not statistically significant[17],[18],[19],[20]

,[22],[24]

.

These four LABA/LAMA inhalers have been demonstrated to improve exercise tolerance, with reported improvements in exercise endurance time compared with placebo of 43–79 seconds, which is likely to be clinically important in COPD patients who have significant functionally impairment[25],[26],[27],[28]

.

Comparison of dual bronchodilators

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 randomised controlled trials comprising 23,168 COPD patients confirmed the effectiveness of LABA/LAMA FDC inhalers compared with monotherapy for the treatment of COPD[29]

. LABA/LAMA inhalers were shown to be more effective than either LABA or LAMA monotherapy at improving lung function, and produce small but significant improvements in symptoms of breathlessness and quality of life. The meta-analysis did not show any clinically significant differences in the effectiveness of different licensed LABA/LAMA FDC inhalers, although a small gradient in efficacy was seen with slightly greater improvements in lung function for Anoro and Ultibro compared with Duaklir and Spiolto. However, in the absence of double-blind randomised controlled comparative studies, these data cannot be assessed as conclusive.

A recent eight-week crossover study comparing Anoro Ellipta® (GSK) to Spiolto Respimat® (Boehringer Ingelheim) in patients with COPD and high levels of symptoms reported significantly greater improvements in lung function for Anoro than for Spiolto (52mL greater improvement in trough FEV1 at eight weeks)[30]

. These results should be interpreted with caution owing to the short-term nature of the study preventing assessment of patient-related outcomes, such as exacerbations and health status, and the potential for bias owing to the open-label nature of this study. The study was also sponsored by GSK who market Anoro. A second crossover study compared 12 weeks’ twreatment with indacaterol/glycopyrronium (Ultibron® 25.5/15.6 micrograms twice daily via a Neohaler® [the US-licensed brand name and dose of indacaterol/glycopyrronium in a Neohaler/Breezhaler device]) to Anoro Ellipta[31]

. This double-blind, double-dummy replicate study was sponsored by Novartis and designed to demonstrate non-inferiority of Ultibron compared with Anoro in terms of lung function after 12 weeks of treatment. While the improvement in FEV1 was similar in both treatment arms, it failed to demonstrate non-inferiority of Ultibron to Anoro, with a small benefit in favour of Anoro; however, this was not clinically important[31]

.

Dual bronchodilators and exacerbations

Both Anoro and Duaklir have been demonstrated to significantly reduce the time to first exacerbation when compared with placebo[17],[18]

. Most studies of LABA/LAMA FDC inhalers in comparison with single long-acting bronchodilator therapy have been performed in COPD patients who had experienced a low rate of exacerbations at baseline, and consequently have failed to demonstrate convincing superiority to long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy in the prevention of exacerbations. Anoro[17],[32],[33]

and Duaklir[18]

had no significant effect on exacerbation rate when compared with either LABA or LAMA monotherapy. Spiolto has been shown to produce a significant reduction in moderate-to-severe exacerbations when compared with olodaterol, but not with tiotropium[22]

. Ultibro produces significant reductions in moderate-to-severe exacerbations when compared with glycopyrronium, but not with tiotropium[23]

.

In recent years, the role of LABA/LAMA inhalers has become recognised as an alternative strategy to ICS/LABA inhalers for the treatment of COPD. Dual bronchodilators have the advantage over ICS/LABA for patients experiencing no exacerbations, with significantly greater improvements in lung function and patient-reported outcomes at 26 weeks[34],[35]

. A significant reduction in COPD exacerbations has also been observed in patients with frequent exacerbations treated with LABA/LAMA when compared with ICS/LABA inhalers. The FLAME study reported that Ultibro Breezhaler produced an 11% reduction (P =0.003) in exacerbations of all severities and a 17% reduction (P <0.001) in moderate-to-severe exacerbations compared with Seretide Accuhaler[36]

. Furthermore, dual bronchodilation was associated with a small but significant improvement in lung function, health status and a lower incidence of pneumonia (3.2% vs. 4.8%; P =0.02)[36]

. In this study, all patients had high levels of breathlessness associated with COPD (modified Medical Research Council [MRC] scale ≥2) and at least one exacerbation in the 12 months prior to commencing the study, but only 19% had at least two exacerbations in the past 12 months[36]

. Consequently, the majority of patients likely met the criteria for GOLD category B using the 2018 definitions[1]

, and so the generalisability of these data for patients with high symptoms and frequent (≥2) exacerbations per year may be uncertain. It should be noted that the effect in exacerbations was independent of whether patients had a high or a low blood eosinophil count (≥2% or <2%, respectively)[36]

.

A recent Cochrane review confirmed these findings that LABA/LAMA FDC inhalers produce greater improvements in FEV1 and more frequently achieve clinically important improvements in quality of life (>4 units change on SGRQ score), fewer exacerbations and a lower risk of pneumonia than ICS/LABA inhalers[37]

.

Place in therapy

While there are no studies available to determine the effect of using combination LABA/LAMA inhalers on adherence or patient preference in comparison with using separate inhalers, the cost of the latter are lower, thus making them an attractive option for patients requiring dual long-acting bronchodilator therapy.

With the caveat that a greater reduction in exacerbation rate by using a LABA/LAMA inhaler instead of an ICS/LABA inhaler has only been demonstrated by Ultibro Breezhaler[36]

, there are currently no convincing data to suggest the superiority of any one LABA/LAMA FDC inhaler over another. As each of the four licensed preparations have the same NHS list price, the choice of which preparation to prescribe is likely to depend on patient preference and their ability to use each device. There are no independent comparisons of these four inhaler devices to suggest that any one device is significantly easier to use, or more likely to be preferred, than any other device, although each manufacturer reports higher levels of preference and greater ease of use in their own sponsored studies[38],[39],[40],[41],[42],[43]

.

For patients experiencing high levels of symptoms but infrequent exacerbations (GOLD category B), current GOLD guidelines recommend the use of LABA/LAMA inhalers as a second-line option in patients who remain symptomatic or with poor health status despite treatment with long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy using either a LABA or LAMA[1]

.

However, it is likely that the majority of patients treated with single long-acting bronchodilators in this category are likely to need ‘stepping up’ to dual long-acting bronchodilators early in treatment. A cross-sectional study of more than 1,000 patients with COPD treated with long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy in the United States reported that the majority continued to experience significant symptoms as measured using the modified MRC dyspnoea scale, irrespective of whether they had mild-to-moderate or severe-to-very-severe airflow limitation[44]

. This suggests that monotherapy with either a LABA or a LAMA may not sufficiently control symptoms in the majority of patients, who would then require additional bronchodilator therapy. An open-label study stepping up patients with COPD of moderate severity who remained symptomatic with either LABA or LAMA monotherapy to indacaterol/glycopyrronium resulted in significant improvements in lung function and breathlessness[45]

, and significant reduction in proportion of patients experiencing a clinically important deterioration[46]

.

A pragmatic approach to treating GOLD category B patients could be to commence patients with high levels of symptoms on a LABA/LAMA inhaler as their first treatment option, rather than following a stepwise approach escalating therapy from LABA or LAMA monotherapy. This strategy would have the potential to maximise lung function, health status and exercise endurance earlier in treatment, rather than delaying maximum symptom control resulting from trialling monotherapy first.

For patients experiencing frequent exacerbations (GOLD category C and D), it may also be prudent to commence dual long-acting bronchodilators as data exist demonstrating superiority in exacerbation prevention compared with ICS/LABA, with a reduction in pneumonia risk.

Triple-combination inhalers

The first two triple-combination inhalers were launched in 2017 (see Table) — Trimbow® (Chiesi), a twice-daily pressurised metered dose inhaler (pMDI) preparation and Trelegy® Ellipta® (GSK), a once-daily dry powder inhaler (DPI). Both products are licensed for maintenance treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe COPD not adequately treated by a combination of an ICS/LABA. This is based on the trials supporting the licence application, which unfortunately does not reflect the “step up” process of the GOLD A, B, C, D guidance of adding in an ICS to LABA/LAMA if the patient continues to exacerbate or experience ongoing severe symptoms. Technically speaking, the terms of the current licence agreement would be breached if a patient was switched from a dual bronchodilator to ICS/LABA/LAMA. In September 2018, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (also known as CHMP) recommended a licence extension for Trelegy Ellipta to allow for this to be used in people not adequately treated with a combination of LABA plus LAMA[47]

, although this is not yet reflected in its summary of product characteristics. Trelegy Ellipta may be the most appropriate of the two devices to switch to if the patient is currently using the Anoro Ellipta device, providing the patient understands that the LABA/LAMA has been discontinued altogether. For Trimbow, the practicalities of switching to this from the current range of LABA/LAMA devices means that inhaler technique training would be required. It is licensed for use with an AeroChamber Plus® spacer device (Trudell Medical UK, Hampshire, UK), which may aid switching.

Comparison studies

The randomised, parallel-group, double-blind, active-controlled TRILOGY study compared Fostair to Trimbow over a 52-week trial period in 1,368 patients across 14 countries[48]

. Primary endpoints were pre-dose FEV1, FEV1 two hours post-dose and the transition dyspnoea index (TDI) score. There was a secondary endpoint of exacerbation frequency over 52 weeks. This study demonstrated that pre-dose FEV1 was improved by 80mL in the Trimbow group and post-dose FEV1 by 110mL. TDI scores were improved but found not to be statistically significant. Exacerbations were reduced by 23% in the Trimbow arm versus Fostair[48]

.

The double-blind, parallel-group, randomised, controlled TRINITY trial compared the effect of Trimbow to Fostair plus tiotropium, and to tiotropium alone, over 52 weeks on the rate of moderate-to-severe exacerbations in a total of 2,691 patients with severe or very severe airflow obstruction (FEV1 <50% predicted), significant symptoms (COPD Assessment Test score ≥10) and at least one or more moderate-to-severe exacerbations in the previous 12 months[49]

. The primary endpoint was moderate-to-severe exacerbation rates. While non-inferiority of Trimbow to an “open triple” combination was demonstrated, there were low numbers of exacerbations during the year-long study, which may be accounted for by the fact that exacerbation rates for the 12 months before study entry were low at an average of 1.2 per year. Similarly, patients were excluded from the trial if they had a history of asthma or allergic rhinitis, or if they were already taking a triple-therapy combination. Triple therapy was superior to tiotropium alone in terms of lung function and exacerbation rate[49]

.

The TRIBUTE study compared Trimbow to indacaterol/glycopyrronium over 52 weeks in a double-dummy, double-blind parallel control group to determine moderate-to-severe exacerbation rates in 1,532 COPD patients with severe or very severe airflow limitation, and at least one moderate or severe exacerbation in the previous year[50]

. Two weeks prior to randomisation, all patients were given indacaterol/glycopyrronium and then either continued on this combination or were randomised to the triple-therapy arm. There was a low exacerbation rate during the study, with a moderate-to-severe exacerbation rate of 0.50 in the Trimbow arm compared with 0.59 in the indacaterol/glycopyrronium arm (relative reduction 15%; P =0.043), which may be attributable to the fact that most patients were infrequent exacerbators at baseline. There was no significant difference in rates of severe exacerbations between the two arms; however, the higher exacerbation rate in the dual bronchodilator arm could be attributable to the fact that any ICS was withdrawn before randomisation[50]

. This study did attempt to ensure that the patients had stabilised prior to randomisation to a small extent; however, similar concerns were not observed in the FLAME study, where patients receiving a dual long-acting bronchodilator had a lower exacerbation rate than in patients continuing their ICS[36]

. No increase in pneumonia rates were observed between the two arms in TRIBUTE (Trimbow had a pneumonia rate of 45 versus 41 per 1,000 patient-years for indacaterol/glycopyrronium), which appears to be the first time that this has been demonstrated in a study[50]

. The reasons behind why this occurred remains a matter of debate, but explanations include the use of a lower inhaled steroid burden with the extra-fine beclometasone particles.

The randomised, double-blind, double-dummy FULFIL study compared the effects of once-daily triple therapy on lung function and health-related quality of life with twice-daily ICS/LABA therapy in 1,810 patients with COPD[51]

. Trelegy Ellipta was compared with twice-daily Symbicort 400/12 Turbohaler over 24 weeks and looked at mean changes from baseline for FEV1 and SGRQ score. Trelegy Ellipta increased FEV1 by 142ml and changed the SGRQ score by –6.6 units, both of which are clinically and statistically significant. The triple-therapy arm also reduced the rate of moderate-to-severe exacerbations by 35% in comparison with the Symbicort arm, which was statistically significant (P =0.02)[51]

.

IMPACT is the first randomised study to compare products within the same inhaler device in a head-to-head study[52]

. This was a 52-week double-blind study using the Ellipta portfolio range of Trelegy versus Relvar versus Anoro, and included in excess of 10,000 patients with moderate-to-very-severe COPD, significant symptoms (COPD assessment test score ≥10) and a history of COPD exacerbations. The primary endpoint was the annual rate of moderate or severe exacerbations during the trial. Secondary endpoints included changes in SGRQ score and time to first exacerbation. Pneumonia rates were also recorded and confirmed radiologically as well as clinically. All patients continued on their standard therapy prior to trial enrolment and before being randomised to the allocated therapy[52]

. In contrast to TRIBUTE[50]

, 70% of patients had at least two moderate or one severe exacerbation in the preceding 12 months, indicating that this was a population of frequent exacerbators[52]

. The results showed that Trelegy use reduced the risk of moderate or severe exacerbations compared with Relvar use or Anoro use (0.91 vs. 1.07 vs. 1.21 exacerbations per year, respectively; P <0.001 for Trelegy vs. Anoro and Trelegy vs. Anoro). A reduction in exacerbation rate was observed irrespective of eosinophil levels, although those patients with eosinophils >150 cells/microlitre did have a greater reduction in exacerbation rates[52]

.

Critical analysis of the IMPACT trial has shown that 18% of the trial population had bronchodilator reversibility of >200mL after administration of albuterol, which raises the question of whether there is an underlying diagnosis (or features) of asthma. The analysis also showed that 67% of patients were taking an ICS prior to randomisation either as part of the “triple” combination or as part of an ICS/LABA regimen; this may have a significant impact on exacerbation rates in this population if they were initially on an ICS prior to randomisation and then this was rapidly withdrawn at the start of the study in patients randomised to LABA/LAMA, rather than undergoing a run-in period. It appears that more patients allocated to LABA/LAMA experienced a first exacerbation within the first month after randomisation than those randomised to ICS/LABA or ICS/LABA/LAMA, although there are no statistical data to confirm or dispute this. However, after the first month, the rate of first exacerbations appears to be similar across all three treatment arms. As a counter-argument to this concern, it should be noted that the proportion of recruited patients exhibiting reversibility to albuterol is broadly similar to that in other studies such as TRIBUTE (13.5%)[50]

and significantly less than FLAME (45%)[37]

, where stopping ICS appears to have had no adverse effects; on the contrary, patients treated with LABA/LAMA had fewer exacerbations than those continuing ICS within an ICS/LABA FDC inhaler. Pneumonia rates were significantly higher in the arms containing ICS in comparison with the LABA/LAMA arm: 8% in the triple-therapy arm versus 7% in the ICS/LABA arm versus 5% in the LABA/LAMA arm (equivalent to a pneumonia rate of 95.8 vs. 61.2 per 1,000 patient-years for Trelegy and Anoro, respectively)[52]

.

Place in therapy

Similar to LABA/LAMA combination inhalers, there are no studies assessing the effect of using combination ICS/LABA/LAMA inhalers on adherence or patient preference in comparison with using separate inhalers. However, the cost of combination inhalers is lower than using separate inhalers, allowing the possibility of financial savings while simplifying treatment for patients.

Both the TRIBUTE and IMPACT trials provide good evidence for the benefits of using a three-drug ICS/LABA/LAMA FDC inhaler compared with an ICS/LABA or even a LABA/LAMA inhaler[50],[52]

. However, there are concerns with the study design and patient recruitment for both studies, such as recruitment of mainly low-exacerbating patients in TRIBUTE[50]

, and rapid de-escalation of ICS at the start of the study rather than at the start of the run-in period in IMPACT[52]

. This reduces confidence that triple inhalers should be used routinely in place of two-drug FDC inhalers, and certainly from IMPACT, concerns about pneumonia with ICS continue.

It may well be prudent to prescribe Trelegy Ellipta and Trimbow pMDI for COPD patients who continue to experience frequent exacerbations despite good adherence and good inhaler technique with two-drug FDC inhalers containing either LABA/LAMA or ICS/LABA.

Currently there are insufficient data to conclusively state a blood eosinophil count that confers a likelihood that an ICS is either indicated or not, and so this cannot be used as a marker to suggest potential superiority or preference in a subgroup of patients for ICS/LABA/LAMA over LABA/LAMA.

Pneumonia

It was in the randomised, double-blind TORCH study that the risk of pneumonia associated with ICS was first recognised. In this three-year study of 6,112 patients, the probability of having pneumonia was 19.6% and 18.3% in the fluticasone propionate/salmeterol and fluticasone propionate groups, compared with 13.3% and 12.3% in the salmeterol and placebo groups, respectively[10]

. The European Medicines Agency has reviewed the risks of pneumonia in ICS-containing inhalers and found that it is common, affecting between 1 in 10 and 1 in 100 COPD patients, and that this risk appears to be a class effect with no conclusive evidence that any ICS carries a higher risk[53]

.

Concerns about pneumonia with ICSs continue to persist with some, including Lipworth et al., who argued strongly that this risk is only associated with fluticasone, but not beclometasone and budesonide owing to its high relative lipophilicity[54]

. However, the argument put forward in the review by Lipworth et al. is flawed in that the case is made on a subjective rather than scientific comparison of data from studies of Trelegy and Trimbow, which were performed in different populations. The IMPACT trial recruited more patients experiencing frequent exacerbations[52]

than the TRIBUTE trial[50]

(70% vs. 18–20%), and so a higher pneumonia rate would be expected in patients with a greater exacerbation history[1]

.

Agusti et al. suggest there is only a possible increased risk for fluticasone compared with other ICSs, and that differences in pneumonia rate observed in studies of fluticasone, beclometasone or budesonide may vary for reasons other than the ICS used[55]

. The explanation behind this is that pneumonia rates may vary between studies as a result of: different study design or adverse event reporting; different patient characteristics increasing pneumonia rate (e.g. older age, lower body mass index, more severe airflow limitation, greater COPD exacerbation rates and low eosinophil counts); and higher ICS dose. In addition, studies containing budesonide tended to be of shorter duration and, therefore, may be less reliable.

Further confusion about differing pneumonia rates resulting from treatment with fluticasone or other ICSs is provided in the TRISTAR trial (NCT02467452)[56]

, which is currently unpublished. Over six months, the rate of pneumonia in COPD patients receiving Trimbow MDI pMDI was not significantly different from patients receiving Relvar Ellipta plus Spiriva® HandiHaler® (Boehringer Ingelheim) (8/578 [1.38%] vs. 11/579 [1.90%]). Publication of the full results and patient demographics are eagerly awaited to determine the impact of these data on practice. It is likely that comparative clinical trials will be required to definitively answer the question of whether any ICS has a higher risk of pneumonia than others.

Stopping inhaled corticosteroids

The emerging consensus in the respiratory community is that ICSs are largely overused in the COPD population. It appears that ICSs should be avoided in the majority of cases unless the patient is very symptomatic and a frequent exacerbator, and potentially if they have elevated blood eosinophil counts. Starting a newly diagnosed patient on inhaled medication is straightforward once the patient has been categorised into GOLD groups A, B, C or D, which also helps the appropriate therapy to be selected and the patient to be monitored for symptom control and exacerbation rates. There is enough evidence to support the use of LABA/LAMA combinations for symptom control and preventing exacerbations. Where things get more complicated is for those patients who appear to be non-eosinophilic, or those who are not frequent exacerbators who are already on ICS-containing products. The question for these patients is how the ICS can be reduced or stopped without fear of exacerbation or loss of symptom control.

WISDOM was a 12-month, randomised, parallel control trial that recruited 2,435 patients with severe or very severe COPD[57]

. They received initial run-in treatment with tiotropium plus Seretide 500 Accuhaler for 6 weeks and were then randomised to either continue the same regimen or to reduce and stop the ICS over the next 12 weeks[57]

. This trial provides some reassurance that in a population without tendency to exacerbate, withdrawal of ICS did not result in an increase in exacerbation rates[57]

. In a post-hoc analysis, those patients with eosinophils >2% of total white blood count who were in the reduced ICS arm tended to have higher exacerbation rates and the risk increased further still in patients with >4% and again in patients with 5% of total white blood count. Interestingly, this was not seen in patients with eosinophils <2%[58]

. It appears that the evidence is beginning to support withdrawal of ICS in the non-eosinophilic population, but the practicalities of this are yet to be determined with regard to gradual withdrawal, communication of this treatment strategy across the primary/secondary care interface and patient understanding of the strategy.

The design of WISDOM[57]

did, however, raise questions as to whether 52 weeks was long enough to sensitively detect exacerbation rates. Although participants in the WISDOM trial had an FEV1 <50% predicted, patients who did not meet the definition of frequent exacerbators by GOLD (≥2 exacerbations in 12 months or ≥1 exacerbation resulting in hospital admission) were allowed to be included[57]

. Only 39% of patients prior to the run-in period were receiving triple therapy, which implies that during the run-in period their treatment had essentially been “stepped up”, which may have influenced the patient outcomes.

These data were recently supported by the SUNSET trial, which assessed the effect of that ICS withdrawal in 1,053 non-frequently exacerbating patients with moderate-to-severe COPD who had been taking long-term triple-inhaled therapy (for at least six months)[59]

. Following a 30-day run in with fluticasone/salmeterol and tiotropium, patients were randomised to continue on the same regimen or were stepped down to indacaterol (110 micrograms) plus glycopyrronium (50 micrograms) once daily. Over a follow-up period of six months, there was a small but clinically insignificant fall in lung function in the ICS withdrawal group and no difference in exacerbations[59]

. Sub-group analysis showed a higher risk of subsequent exacerbations in the ICS withdrawal group in patients with an eosinophil count ≥300 cells/microlitre[59]

, suggesting that these patients would benefit from ICS/LABA/LAMA rather than LABA/LAMA.

The consequences of ICS withdrawal in the long term are unknown, but there may potentially be a reduction in pneumonia rates and minor side effects (e.g. oral thrush and dysphonia).

Updating COPD guidelines

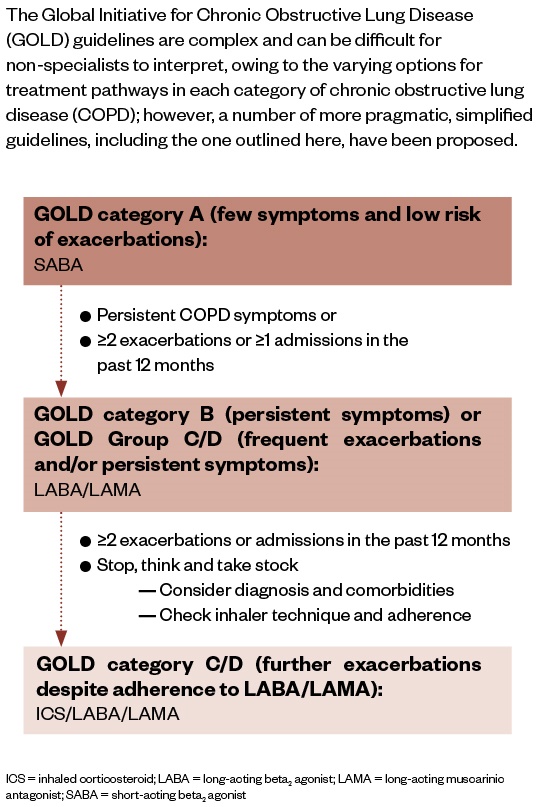

The place of FDC inhalers containing ICS/LABA, LABA/LAMA or ICS/LABA/LAMA in therapy is still being debated, with some in favour of early use of triple-combination inhalers, and others urging a more cautious approach, restricting the use of ICS. The GOLD guidelines[1]

are complex and can be difficult for non-specialists to interpret owing to the varying options for treatment pathways in each A, B, C, D category of COPD; however, a number of more pragmatic, simplified guidelines have been proposed[60],[61],[62]

, such as those used in two regions in Yorkshire, UK (see Figure).

Figure: Example pragmatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease algorithm used in Yorkshire, UK

Source: The Pharmaceutical Journal

Conclusion

FDC inhalers offer advantages to patients by simplifying complex inhaler regimens. Dual long-acting bronchodilator (LABA/LAMA) inhalers achieve clinical and statistically greater improvements in lung function and patient outcomes than placebo, and smaller but important improvements compared with long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy. It appears that dual long-acting bronchodilator (LABA/LAMA) inhalers may also prevent COPD exacerbations to a greater extent than ICS/LABA inhalers, without the risk of pneumonia from ICS. The introduction of the new triple-combination inhalers (ICS/LABA/LAMA) achieve incrementally greater reduction in exacerbation rates compared with LABA/LAMA inhalers and the place in therapy appears to be for those most symptomatic with a high exacerbation rate.

Currently there is no difference in costs between UK-licensed combination inhalers within each class, and no firm evidence that any one within each the class is superior or safer than another. The choice of brand and inhaler device to prescribe will depend on patient preference and the ability to use the device. Inhalers should be prescribed by brand to avoid potential confusion once inhaler technique has been optimised.

Financial and conflicts of interests disclosure

Helen Meynell has received payment for educational events and/or conference sponsorship from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Napp, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. Toby Capstick has received payment for educational events and/or conference sponsorship from Almirall, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GSK, Napp, Novartis, Pfizer and Teva. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

References

[1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for diagnosis, management, and prevention of COPD. 2018. Available at: http://goldcopd.org (accessed November 2018)

[2] British Lung Foundation. The battle for breath — the impact of lung disease in the UK. 2016. Available at: https://www.blf.org.uk/policy/the-battle-for-breath-2016?_ga=2.17819513.1500914910.1530564339-822340970.1417599165 (accessed November 2018)

[3] Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1128–1138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909883

[4] NHS England. Overview of potential to reduce lives lost from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 2014. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/rm-fs-6.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[5] National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG101]. 2010. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG101 (accessed November 2018)

[6] National Institute for Heath and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management (update). In development [GID-NG10026]. 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-ng10026 (accessed November 2018)

[7] Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. Available at: http://www.medicinescomplete.com (accessed November 2018)

[8] Calverley P, Pauwels R, Vestbo J et al. Combined salmeterol and fluticasone in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361(9356):449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12459-2

[9] Calverley P, Boonsawat W, Cseke N et al. Maintenance therapy with budesonide and formoterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Resp J 2003;22(6):912–919. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00027003

[10] Calverley P, Anderson JA, Celli B et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356(8):775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070

[11] Wedzicha JA, Singh D, Vestbo J et al. Extrafine beclomethasone/formoterol in severe COPD patients with history of exacerbations. Resp Med 2014;108(8):1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.05.013

[12] Dransfield MT, Borbeau J, Jones PW et al. Once-daily inhaled fluticasone furoate and vilanterol versus vilanterol only for prevention of exacerbations of COPD: two replicate double-blind, parallel-group, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1(3):210–223. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70040-7

[13] European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) assessment report: Aerivio Spiromax: international non-proprietary name: salmeterol / fluticasone propionate. 2016. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002752/WC500212331.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[14] Swedish Medical Products Agency. Public assessment report scientific discussion: Airflusal Forspiro (salmeterol xinafoate, fluticasone propionate). 2013. Available at: https://docetp.mpa.se/LMF/Airflusal%20Forspiro,%20inhalation%20powder,%20pre-dispensed%20ENG%20PAR_09001be68046a13b.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[15] European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) Assessment Report: DuoResp Spiromax: International non-proprietary name: Budesonide / formoterol. 2014. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/002348/WC500167183.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[16] Swedish Medical Products Agency. Public assessment report scientific discussion: Fobumix Easyhaler (budesonide, formoterol fumarate dihydrate). 2017. Available at: https://docetp.mpa.se/LMF/Fobumix%20Easyhaler%20inhalation%20powder%20ENG%20sPAR_09001be681a1debf.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[17] Donohue JF, Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kilbride S et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg in COPD. Respir Med 2013;107(10):1536–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.001

[18] Singh D, Jones PW, Bateman ED et al. Efficacy and safety of aclidinium bromide/formoterol fumarate fixed-dose combinations compared with individual components and placebo in patients with COPD (ACLIFORM-COPD): a multicentre, randomised study. BMC Pulm Med 2014;14:178. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-178

[19] Singh D, Ferguson GT, Bolitschek J et al. Tiotropium + olodaterol shows clinically meaningful improvements in quality of life. Respir Med 2015;109(10):1312–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.08.002

[20] D’Urzo A, Rennard SI, Kerwin EM et al. Efficacy and safety of fixed-dose combinations of aclidinium bromide/formoterol fumarate: the 24-week, randomized, placebo-controlled AUGMENT COPD study. Respir Res 2014;15:123. doi: 10.1186/s12931-014-0123-0

[21] D’Urzo, A, Rennard SI, Kerwin EM et al. A randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled, long-term extension study of the efficacy, safety and tolerability of fixed-dose combinations of aclidinium/formoterol or monotherapy in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 2017;125:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2017.02.008

[22] Buhl R, Maltais F, Abrahams R et al. Tiotropium and olodaterol fixed-dose combination versus mono-components in COPD (GOLD 2–4). Eur Resp J 2015;45(4):969–979. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00136014

[23] Wedzicha JA, Decramer M, Ficker JH et al. Analysis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations with the dual bronchodilator QVA149 compared with glycopyrronium and tiotropium (SPARK): a randomised, double-blind, parallel-group study. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1(3):199–209. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(13)70052-3

[24] Singh D, Gaga M, Schmidt O et al. Effects of tiotropium + olodaterol versus tiotropium or placebo by COPD disease severity and previous treatment history in the OTEMTO® studies. Respir Res 2016;17:73. doi: 10.1186/s12931-016-0387-7

[25] Maltais F, Singh S, Donald AC et al. Effects of a combination of umeclidinium/vilanterol on exercise endurance in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: two randomized, double-blind clinical trials. Ther Adv Respir Dis 2014;8(6):169–181. doi: 10.1177/1753465814559209

[26] Watz H, Troosters T, Beeh KM et al. ACTIVATE: the effect of aclidinium/formoterol on hyperinflation, exercise capacity, and physical activity in patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2017;12:2545–2558. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S143488

[27] O’Donnell DE, Casaburi R, Frith P et al. Effects of combined tiotropium/olodaterol on inspiratory capacity and exercise endurance in COPD. Eur Respir J 2017;49(4):1601348. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01348-2016

[28] Beeh KM, Korn S, Beier J et al. Effect of QVA149 on lung volumes and exercise tolerance in COPD patients: the BRIGHT study. Respir Med 2014;108(4):584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.01.006

[29] Calzetta L, Rogliani P, Matera MG & Cazzola M. A systematic review with meta-analysis of dual bronchodilation with LAMA/LABA for the treatment of stable COPD. Chest 2016;149(5):1181–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.646

[30] Feldman GJ, Sousa AR, Lipson DA et al. Comparative efficacy of once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol and tiotropium/olodaterol therapy in symptomatic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomised study. Adv Ther 2017;34(11):2518–2533. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0626-4

[31] Kerwin E, Ferguson GT, Sanjar S et al. Dual bronchodilation with indacaterol maleate/glycopyrronium bromide compared with umeclidinium bromide/vilanterol in patients with moderate-to-severe COPD: results from two randomised, controlled, cross-over studies. Lung 2017;195(6):739–747. doi: 10.1007/s00408-017-0055-9

[32] Decramer M, Anzueto A, Kerwin E et al. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium plus vilanterol versus tiotropium, vilanterol, or umeclidinium monotherapies over 24 weeks in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from two multicentre, blinded, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med 2014;2(6): 472–486. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70065-7

[33] Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kaelin T, Richard N et al. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg and tiotropium 18 mcg in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of a 24-week, randomized, controlled trial. Respir Med 2014;108(12):1752–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.002

[34] Singh D, Worsley S, Zhu CQ et al. Umeclidinium/vilanterol versus fluticasone propionate/salmeterol in COPD: a randomised trial. BMC Pulm Med 2015;15:91. doi: 10.1186/s12890-015-0092-1

[35] Vogelmeier CF, Bateman ED, Pallante J et al. Efficacy and safety of once daily QVA149 compared with twice daily salmeterol-fluticasone in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ILLUMINATE): a randomised, double-blind, parallel group study. Lancet Respir Med 2013;1(1):51–60. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(12)70052-8

[36] Wedzicha JA, Banerji D, Chapman KR et al. Indacaterol-glycopyrronium versus salmeterol-fluticasone for COPD. N Engl J Med 2016;374(23);2222–2234. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1516385

[37] Horita N, Goto A, Shibata Y et al. Long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) plus long-acting beta-agonist (LABA) versus LABA plus inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) for stable chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;(2):CD012066. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012066.pub2

[38] Riley JH, Tabberer M, Richard N et al. Correct usage, ease of use, and preference of two dry powder inhalers inpatients with COPD: analysis of five phase III, randomized trials. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11(1):1873–1880. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S109121

[39] van der Palen J, Thomas M, Chrystyn H et al. A randomised open-label cross-over study of inhaler errors, preference and time to achieve correct inhaler use in patients with COPD or asthma: comparison of ELLIPTA with other inhaler devices. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2016;26:16079. doi: 10.1038/npjpcrm.2016.79

[40] van der Palen J, Ginko T, Kroker A et al. Preference, satisfaction and errors with two dry powder inhalers in patients with COPD. Expert Opin Drug Deliv 2013;10(8):1023–1031. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2013.808186

[41] Miravitlles M, Montero-Caballero J, Richard F et al. A cross-sectional study to assess inhalation device handling and patient satisfaction in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11(1):407–415. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S91118

[42] Chapman KR, Fogarty CM, Peckitt C et al. Delivery characteristics and patients’ handling of two single-dose dry-powder inhalers used in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2011;6:353–363. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S18529

[43] Molimard M, Raherison C, Lignot S et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation and inhaler device handling: real-life assessment of 2935 patients. Eur Respir J 2017;49(2):1601794. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01794-2016

[44] Dransfield MT, Bailey W, Crater G et al. Disease severity and symptoms among patients receiving monotherapy for COPD. Prim Care Respir J 2011;20(1):46–53. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00059

[45] Vogelmeier CF, Gaga M, Aalamian-Mattheis M et al. Efficacy and safety of direct switch to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with moderate COPD: the CRYSTAL open-label randomised trial. Respir Res 2017;18:140. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0622-x

[46] Greulich T, Kostikas K, Gaga M et al. Indacaterol/glycopyrronium reduces the risk of clinically important deterioration after direct switch from baseline therapies in patients with moderate COPD: a post hoc analysis of the CRYSTAL study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;13:1229–1237. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S159732

[47] European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. Summary of opinion (post authorisation): Trelegy Ellipta: fluticasone furoate / umeclidinium / vilanterol fluticasone. 2018. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/smop/chmp-post-authorisation-summary-positive-opinion-trelegy-ellipta_en.pdf (accessed November 2018)

[48] Singh D, Papi A, Corradi M et al. Single inhaler triple therapy versus inhaled corticosteroid plus long-acting β2-agonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRILOGY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016;388(10048):963–973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31354-X

[49] Vestbo J, Papi A, Corradi M et al. Single inhaler extrafine triple therapy versus long-acting muscarinic antagonist therapy for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRINITY): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017;389(10082):1919–1929. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30188-5

[50] Papi A, Vestbo J, Fabbri L et al. Extrafine inhaled triple therapy versus dual bronchodilator therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (TRIBUTE): a double-blind, parallel group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;391(10125):1076–1084. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30206-X

[51] Lipson DA, Barnacle H, Birk R et al. FULFIL Trial: Once-daily triple therapy for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Resp Crit Care Med 2017;196(4):438–446. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0449OC

[52] Lipson DA, Barnhart F, Brealey N et al. Once-daily single-inhaler triple versus dual therapy in patients with COPD. New Eng J Med 2018;378(18):1671–1680. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1713901

[53] European Medicines Agency. Inhaled corticosteroids containing medicinal products indicated in the treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 2016. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/human/referrals/Inhaled_corticosteroids_for_chronic_obstructive_pulmonary_disease/human_referral_prac_000050.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac05805c516f (accessed November 2018)

[54] Lipworth B, Kuo CR & Jabbal S. Current appraisal of single inhaler triple therapy in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018:13:3003–3009. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S177333

[55] Agusti A, Fabbri LM, Singh D et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: Friend or foe? Eur Respir J 2018; in press. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01219-2018

[56] EU Clinical Trials Register. A multinational, multicentre, randomised, open-label, active-controlled, 26-week, 2-arm, parallel group study to evaluate the non-inferiority of fixed combination of beclometasone dipropionate plus formoterol fumarate plus glycopyrronium bromide administered via pMDI (CHF 5993) versus fixed combination of fluticasone furoate plus vilanterol administered via DPI (Relvar®) plus tiotropium bromide (Spiriva®) for the treatment of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Available at: https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2014-001487-35/results (accessed November 2018)

[57] Magnussen H, Disse B, Rodriguez-Roisin R et al. Withdrawal of inhaled glucocorticoids and exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med 2014;371(14):1285–1294. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407154

[58] Watz H, Tetzlaff K, Wouters EFM et al. Blood eosinophil count and exacerbations in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after withdrawal of inhaled corticosteroids: a post-hoc analysis of the WISDOM trial. Lancet Respir Med 2016;4(5):390–398. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(16)00100-4

[59] Chapman KR, Hurst JR, Frent SM et al. Long-term triple therapy de-escalation to indacaterol/glycopyrronium in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SUNSET): A randomized, double-blind, triple-dummy clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2018;198(3):329–339. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201803-0405OC

[60] Lipworth B & Jabbal S. A pragmatic approach to simplify inhaler therapy for COPD. Lancet Resp Med 2017;5(9):679–681. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30264-3

[61] Mak V, Keeley D & Gruffydd Jones K. Treatment guidelines for COPD — Going for GOLD? Primary Care Respiratory Update 2017;4(2):19–24

[62] Miravitlles M & Anzueto A. A new 2-step algorithm for treatment of COPD. Eur Respir J 2017;49(2):1602200. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02200-2016