Abstract

Background: Social prescribing is a tool for healthcare professionals to help connect people in their communities to local, non-clinical groups and services. It aims to improve mental health and physical wellbeing, and reduce negative health impacts of loneliness, poor health and disability. As a funded policy shift in the UK care model, it brings together networks of multidisciplinary health professionals with community-based services, such as those delivered by the voluntary sector. Despite community pharmacy gaining a policy mention, little is known about whether it is enacting social prescribing in daily practice or is included in the envisaged local network interventions.

Objective: This review aims to explore the involvement of community pharmacy in social prescribing.

Method: Medical and social electronic databases were systematically searched. A narrative synthesis was undertaken to present the data.

Results: Six studies were included in the review. The quality of reporting in the studies varied. It was found that community pharmacy has a role in: non-clinical interventions, acting as a social prescriber and service provider; biomedical and psychosocial assessments for targeted referral to non-clinical services; and a mixture of referral and collaborative service delivery. Pharmacists predominantly had a biomedical approach to social prescribing, targeting populations predetermined as having higher medical needs, such as the elderly and vulnerable. Training for pharmacists, when present, included skills in assessment and intervention delivery. Studies included biomedical outcomes, such as blood pressure, blood glucose, HbA1c and cholesterol; achieving significant improvements over short to long-term timeframes, as well as social and community benefits.

Conclusion: The current evidence around community pharmacy involvement in social prescribing is limited. Community pharmacy is involved in referring and connecting people with existing initiatives and has demonstrated intervention delivery. The limited literature may not represent the full scope of pharmacy involvement in this important area, limiting both the ability to draw conclusions and any benefit from sharing of experience between practitioners. Engaging in social prescribing may have the potential to enrich the profession and benefit the patients and wider communities, yet more evidence is needed to ascertain this.

Keywords: Social prescribing; community pharmacy; signposting, referral.

Original submitted: 10 February 2021; Revised submitted: 21 June 2021; Accepted for publication: 23 June 2021; Published online: 21 July 2021.

Key points

- Social prescribing brings together networks of multidisciplinary healthcare professionals to improve mental health and physical wellbeing through community-based services;

- Current evidence suggests community pharmacy involvement in social prescribing is limited but there is potential for more meaningful involvement;

- Evidence indicates community pharmacies refer and connect people with existing initiatives, as well as delivering some social prescribing interventions;

- To further utilise community pharmacies in social prescribing, the funding frameworks need to reflect the way community pharmacies operate and receive funding for service provision.

Introduction

Social prescribing, sometimes termed community referral, is a mechanism for connecting primary healthcare with community and voluntary sector activities and services[1–3]. It uses non-clinical options to improve the mental and physical health and wellbeing of patients, by reducing loneliness and improving engagement in groups and activities in local communities[1]. Social prescribing may see patients participate in a broad range of activities including art therapy, exercise classes, walking groups, volunteering or choirs[4]. Poor evidence for the benefits of social prescribing has been attributed to the limits of self-reporting data, complex interventions with multiple factors, small studies and researcher bias[1,5,6]. Qualitative studies, however, suggest participants perceive benefits and value their experience[7]. In Western welfare states such as the UK, social prescribing is supported by an economic savings rationale, relieving pressure on public health systems[8]. Thus, UK policymakers have committed to increasing funding for social prescribing initiatives, ranging from those with specific focus, such as singing groups for people with chronic lung conditions, to holistic hub models targeting physical, mental, social and financial wellbeing, indicating expected benefits on public health and wellbeing[9–11]. Yet there is disparity and lack of consensus in the existing definitions, pathways and processes of social prescribing, as well as available supporting evidence[12].

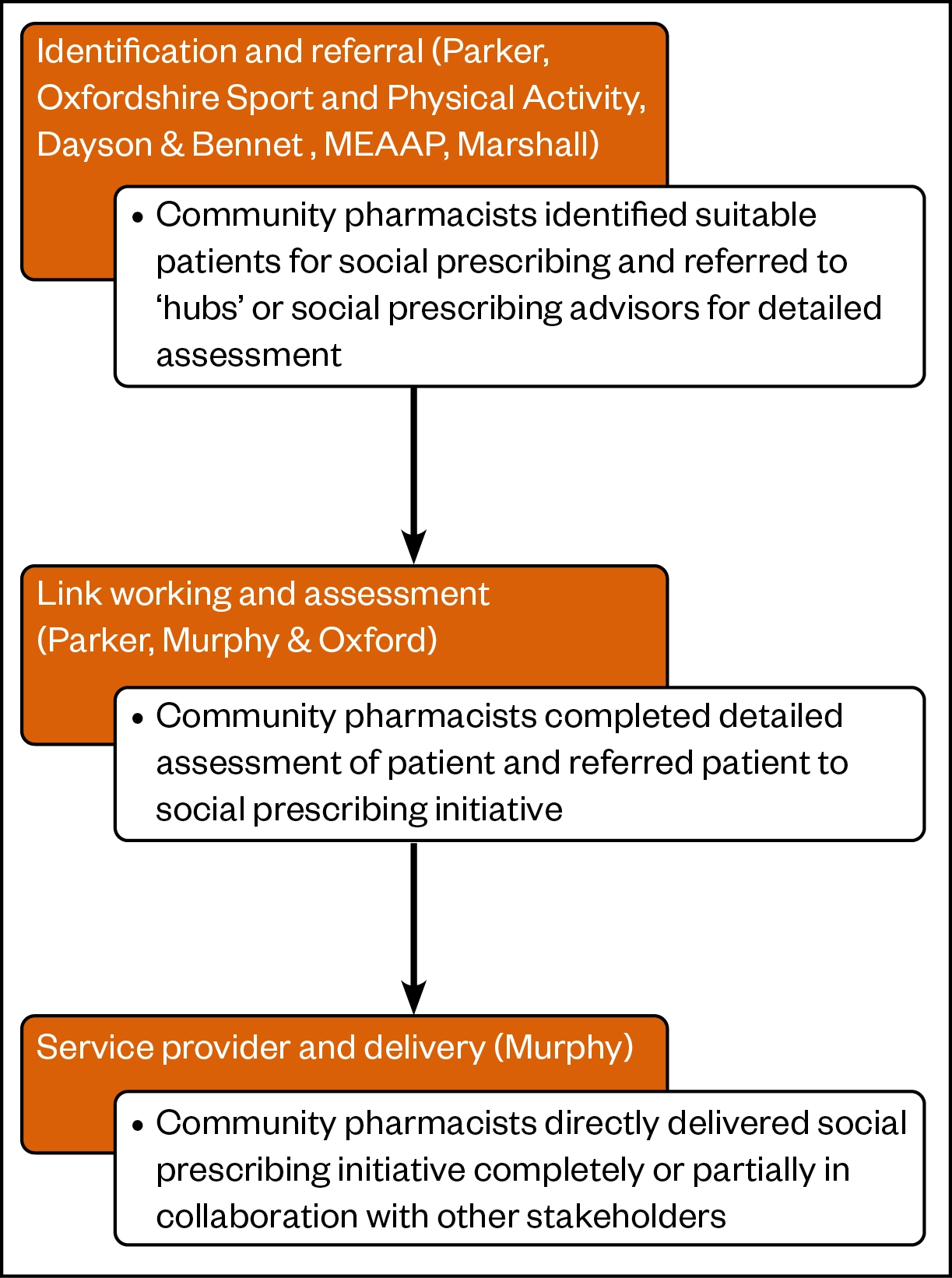

Social prescribing can be conceptualised through three roles. The first role, often termed the referrer, identifies patients who would benefit, such as those with long-term conditions or who are socially isolated; this occurs through general practice in countries such as the UK[13]. The second role is the link worker, who receives the referral and meets with the patient to assess and co-create an individualised plan based on their needs[3,14–17]. The link worker has good knowledge and connections with local services and is often situated within primary health teams[3,14,16]. The final role is the service provider or community group, a diverse range of agents that may also receive government funding[18].

Within the current conceptualisation of social prescribing, the role of community pharmacy is typically vague or described as an aspirational adjunct in a network of person-centred stakeholders[19]. For example, in the UK, it is envisaged that patients would benefit if pharmacies and other allied healthcare also referred patients to link workers[20]. Yet, remuneration is absent in current funding models for social prescribing for pharmacy. The current pharmacy contractual framework includes signposting directly to local services, an intervention that could be seen as ‘light touch’ social prescribing[21,22]. There is potential for community pharmacy to be meaningfully embedded and involved in social prescribing beyond signposting. Yet, the literature rarely mentions pharmacy in the list of stakeholders who conduct link worker, service provider or patient identification roles.

There is some evidence that points to the potential for community pharmacy to contribute to social prescribing roles. In the UK, many community pharmacies operate as Healthy Living Pharmacies and have been given this status in recognition of their efforts in meeting local needs and improving health and wellbeing; this holistic focus aligns with the ethos of social prescribing and may positively impact the preparedness of community pharmacies to be involved[19,23]. Additionally, users of community pharmacy services recognise that community pharmacists offer wide ranging and valued healthcare, including expert advice for supporting people with long-term health conditions[24]. Further, pharmacies have perhaps the highest frequency of contact with these and other vulnerable populations, such as older people, that the government wants to target through social prescribing initiatives[11]. Regular points of patient contact include structured services with referral mechanisms, where enquiring about people’s broader social needs is best practice, but not necessarily always a priority, with current workloads and remuneration frameworks[25,26].

Existing work has indicated that pharmacy practice may adopt a narrow view that overly directs attention towards the supply of medication, to avoid overstepping professional boundaries[27]. This may limit community pharmacy from realising its potential within the social prescribing landscape.

As pharmacists are increasingly used for delivering public health and primary care services, attention must be given to research in this area to ensure that community pharmacists can provide evidence-based public health interventions. There is, however, little work that has explored the role of community pharmacists in social prescribing thus far to identify if, and how, community pharmacists may be enacting social prescribing.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this review is to explore the involvement of community pharmacy in social prescribing, to identify evidence of social prescribing in community pharmacy, and assess the extent and types of pharmacy involvement to inform the development of pharmacist roles in this area of practice.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This review follows PRISMA Guidelines for reporting systematic reviews[28]. Studies were assessed using the strengthening and reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) tool[29]. The review protocol is registered with PROSPERO [registration number CRD42019135729].

Eligibility criteria

Records were selected for inclusion based on the following criteria:

i) included social prescribing;

ii) included community pharmacy or pharmacist involvement;

iii) reports or articles on an intervention;

iv) written in English.

For the purpose of this study, social prescribing was defined (without regard to who performs the role) as any intervention involving the identification and referral of individuals to an activity or service in a community setting to improve mental health and physical wellbeing by addressing emotional, social or practical needs.

Exclusion criteria

Excluded studies did not meet the inclusion criteria.

Information sources

A systematic search included electronic databases including Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), EMBASE, MEDLINE, and PsycINFO. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE). Databases were searched individually with keywords to combine concepts. Additional records were identified via the snowball method through professional research networks, grey literature and searching the references of the included records. Searches were conducted up to 28 August 2020 with no lower date limit.

Search

Key search terms were identified by completing simple searches in the databases with the phrase ‘social prescribing’ and reviewing the keywords used in the relevant articles found in these searches. The search was limited to the English language. No other limits were applied to the search. The combination of search terms used were social prescribing OR wellbeing programme OR non-medical referral OR community referral OR community project OR community programme AND pharmac*.

Study selection

Titles and abstracts resulting from the database search were reviewed by the authors (LL and APR) and full texts were retrieved for relevant articles or articles that did not provide enough information in the title or abstract. The full texts of eligible articles were then systematically reviewed for information about social prescribing and pharmacy or pharmacists. Articles that met the inclusion criteria were reviewed in their entirety using the STROBE tool. Figure 1 outlines the study selection process.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias was not assessed in individual studies or across studies.

Quality assessment

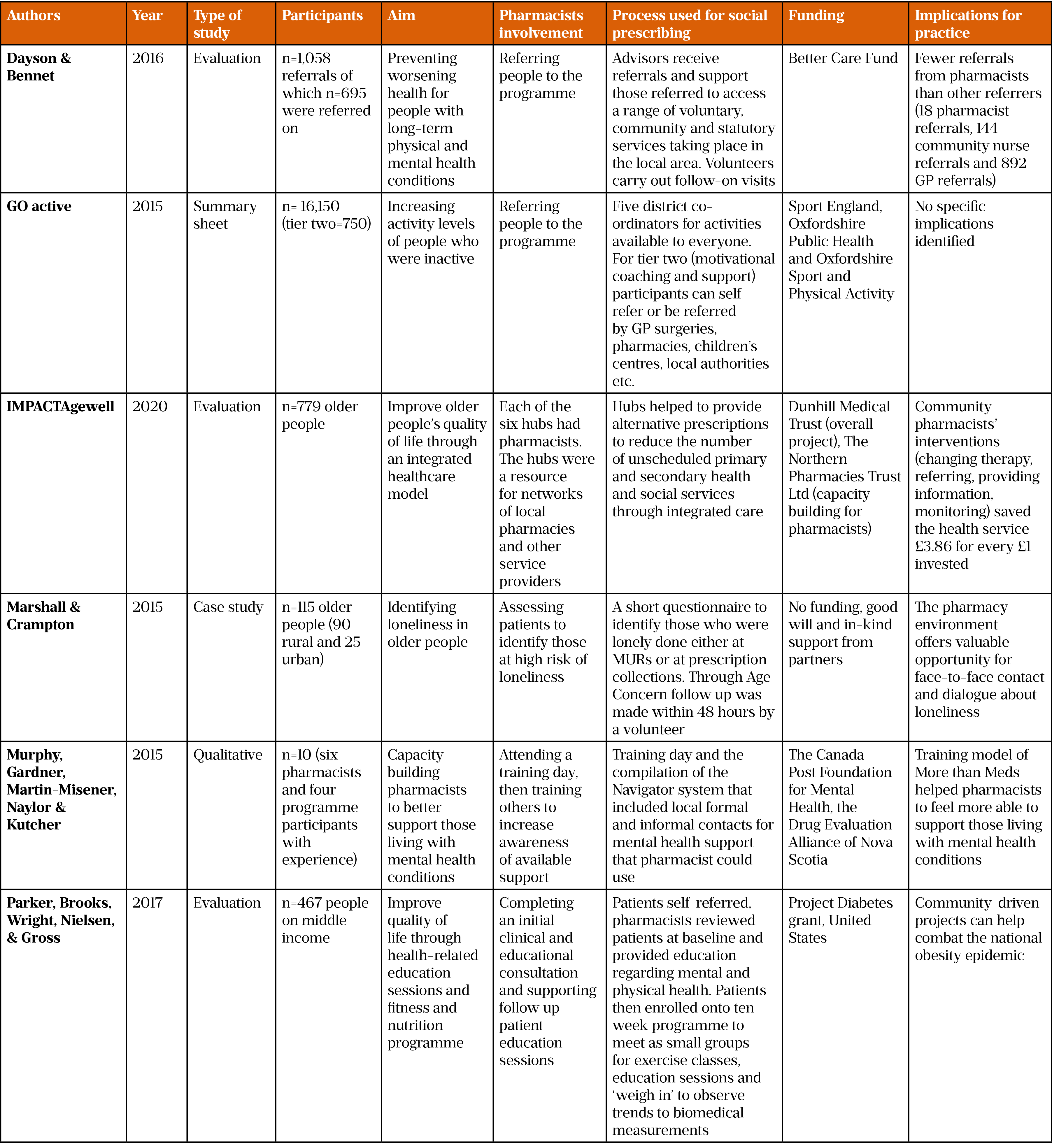

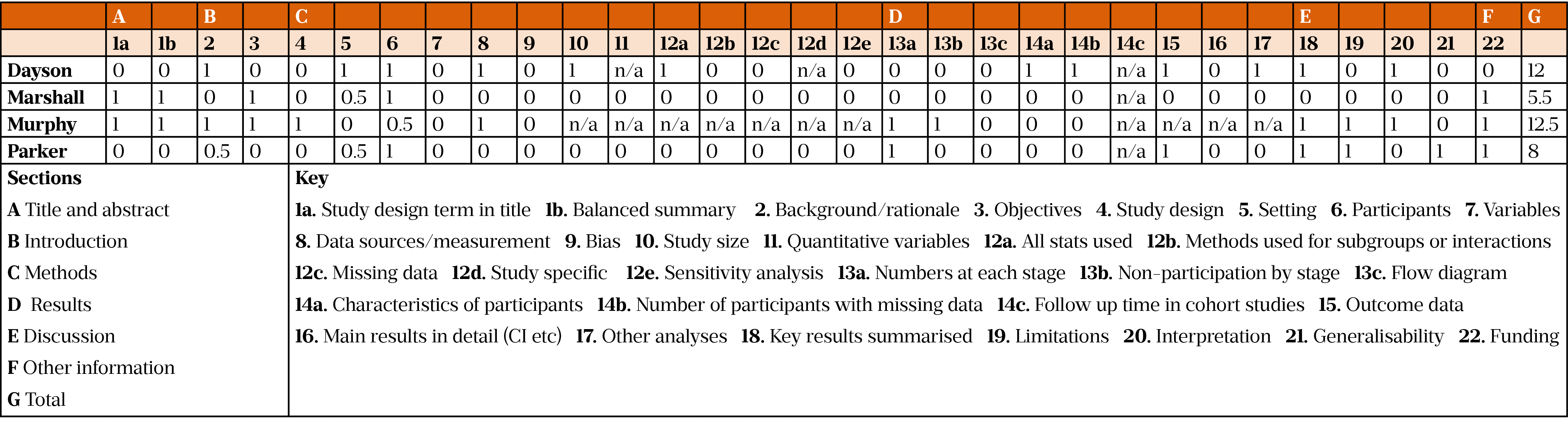

The quality of the included records was assessed using the STROBE tool[29]. This tool provides a score for the study using a 22-item checklist that relates to introduction, method and results. Three of the included studies were evaluations; of these, one was assessed using the tool but two were not as they were not reported in a peer reviewed format[30–32]. The studies were scored independently by the authors (LL, AR) and in case of disagreement, reconciliation was sought with the third author (SH). Of the scored studies, overall scores varied from 5.5 to 12.5[30,33,34]. All studies reported on the participants apart from one[33]. None of the studies discussed bias or missing data nor provided flow chart on participation. The STROBE scores are available as supplementary material.

Data collection and synthesis

Data collection was conducted manually by the authors. Two of the authors extracted the data independently (LL, AR) and the extracted data was then quality checked against the original articles (SH). Data were summarised and recorded using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Data were synthesized using a narrative approach outlined by the narrative synthesis in systematic reviews guidance document[35]. Data were categorised into discrete descriptive themes by the authors independently. Descriptive themes were synthesized through discussion until consensus. Analytic themes were developed through additional reflection and discussion to identify findings that ‘go beyond’ the primary descriptive themes.

Results

The search strategy identified 4,000 records for screening; of these, 3,976 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Twenty-four records were reviewed at full text. Six met the inclusion criteria and had data extracted[30–34,36].

Study characteristics

Four of the studies were conducted in the UK, one study in Canada and one in the US[34,36]. Sample sizes in the studies were variable, ranging from 6 to 1,058 participants[30,34]. The majority of studies identified themselves as social prescribing initiatives except two, which did not mention the term ‘social prescribing’ but did meet our definition of social prescribing[33,34]. All studies were published after 2015. Study details can be seen in Table 1.

In one study, pharmacists were the participants, whereas the other studies focused on people who had been referred to a social prescribing initiative[34]. These included older people, people with mental health issues, middle income residents, physically inactive individuals and those considered vulnerable[30–34,36]. Two of the interventions allowed referral through self-identification; of these, one also allowed access through referrers [31,36]. Studies involving just referrers used criteria such as age or presence of health conditions to identify patients[32,33]. Three of the studies involved only pharmacists as referrers, and three had multiple professionals as referrers[30–34,36].

Impact of pharmacists’ involvement in social prescribing

The impact of pharmacists’ contribution to social prescribing was measured using a variety of mechanisms, which prevents direct comparison between studies. One study demonstrated positive impacts on health and wellbeing, such as reductions in blood pressure, blood glucose, HbA1C and total cholesterol, sustainable over a three-year period[36]. Short-term improvements in quality of life as well as improved perceptions of health were also reported[30,31]. Improved community benefits were observed, including engagement and interaction between community members in activities (e.g. races) and physical spaces (e.g. gardens)[30,36]. A reduction in accessing other health services was also seen and one study reported improving the financial wellbeing of participants[30,31]. Two studies reported findings relating to cost-effectiveness[30,32].

Types of social prescribing interventions

Community pharmacists were involved in a range of social prescribing interventions including community gardening projects; projects to address inactivity such as exercise classes; running mental health support sessions; combating loneliness; and increasing quality of life for patients with diabetes through community education projects[31,33,34,36]. Multiple modes of interventions were described in the reviewed articles — including face-to-face consultations, telephone consultations and written communication via email and post — although most interventions took place in person[33].

Pharmacist involvement

The large majority of studies report pharmacists identifying patients, with the use of referral criteria or specific assessment and acting as link workers to refer patients to other organisations[30–34,36]. Only one study reported pharmacists acting as service providers[34] (Figure 2).

Studies reported single or multiple interaction interventions that involved a pharmacist. The majority of evidence reports interventions using a single interaction with a pharmacist to complete biomedical and/or psychosocial assessments to refer patients to other initiatives, such as gardening and exercise[30–32,36]. The role of the pharmacist was limited to a single point of contact or ‘touch point’; once the patients’ needs were identified, they were linked to other organisations.

The ‘More than Meds’ programme is an example of pharmacists delivering a social prescribing initiative[34]. A pharmacist attended a training day on providing medication and non-medication-related support via their community pharmacy to people with mental health issues in the community, involving multiple interactions with pharmacists over time. A multiple interaction intervention appeared to create capacity within the pharmaceutical workforce to provide direct social support to patients, as well as build networks for patients to be identified and referred on to other providers of social support within the community more informally (i.e. practice nurses, community nurses). Interactions such as these provide further identification and link working opportunities, by embedding pharmacists in the social prescribing network.

Formal versus informal tools for identifying needs

Studies typically reported structured interventions with pharmacists in an identification, assessment and referral role, utilising communication, diagnostic skills and connections within the community. An intervention reported by Parker et al. used consultations with pharmacists to refer patients to a ten-week social intervention programme that included group-based activities, such as gardening and exercises. Other interventions included training that upskilled pharmacists to recognise when social interventions are needed using formal referral tools, while simultaneously building networks to increase informal referrals[34]. For example, the Navigator tool, which had details of all formal and informal support available locally, enabled pharmacists to formally consult with patients to identify care opportunities that would best meet their needs[34]. The GO active study used pharmacists, alongside other community-based referrers such as GPs and children’s centres, to refer patients who fulfilled the programme’s referral criteria[31].

Marshal and Crampton used a questionnaire during pharmacy consultations and prescription collections to identify if participants were lonely[33]. The questionnaire included patient demographic and contact information. An Older People’s Area Link (OPAL) from Age UK collected the completed questionnaires each day and reviewed them to identify people who may be experiencing loneliness and contacted these patients within 48 hours. Alternatively, Murphy et al. reported pharmacists learning about the value to patients of referrals following ‘partnering’ with mental health patients, an activity that helped build bridges across the care divide so that the patients could be signposted and referred on informally[34].

Pharmacists also completed formal consultations with patients to review both physical, biomedical and pharmaceutical care, as well as social and educational needs[36]. Patients were then referred on to different programmes depending on the pharmacist’s judgement of their needs. Although the authors reported that the focus of the study was on the biomedical impact of social intervention (e.g. group-based exercise classes), the data presented that social care outcomes may also have been measured (e.g. engagement in community events and spaces, such as races and gardens)[36].

Link working; a double-pronged approach

The literature described two modes of community pharmacists acting as a link worker or connector. The first enabled community pharmacists to make referrals directly to a programme (that was delivered internally by the community pharmacy or externally by another provider). This indicates that pharmacists can make appropriate assessments and provide alternative services to prescription services by linking patients to suitable social interventions. However, two studies also described pharmacists linking patients directly to the service provider; community pharmacists linked patients to an intermediary organisation, which then performed its own assessment and linking to suitable social interventions[30,32]. In these studies, community pharmacists, along with other healthcare professionals, such as community nurses and general medical practitioners, signposted or linked patients to ‘hubs’ or ‘advisors’ within a voluntary organisation, which then made further recommendations or referrals to specific programmes. This indicates evidence of a two-tiered approach where trained pharmacists can identify programmes to meet patients’ needs and make direct referrals as well as pharmacists, who perhaps with less experience, can refer to an intermediary link-working organisation. The linking role for community pharmacy is potentially an embedded, ongoing role as a community provider and connector rather than a separate, independent role of a link worker widely used in social prescribing interventions where the sole focus is on making the connections and supporting individuals[10].

Discussion

The aim of this review was to explore and assess the involvement of community pharmacy in social prescribing. The evidence suggests that pharmacists are involved in social prescribing in multiple ways: indirectly by assessing patients and referring to other providers, but also directly by running programmes of interventions over multiple consultations[30–34,36]. The literature indicated pharmacists can both assess patients, deliver social prescribing interventions and refer to appropriate social prescribing interventions, as well as refer patients to other providers for more complex assessment.

Comparison with other areas of social prescribing

Our findings suggest pharmacists are mostly involved in social prescribing as referrers. This could be argued to be an alternative version of signposting, a long-standing part of community pharmacy practice. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) conducted a review on signposting from community pharmacies, including only studies that were either randomised control trials (RCTs) or systematic reviews of RCTs[37]. Very few studies fulfilled NICE’s inclusion criteria, meaning a considerable portion of evidence that could shape policy and practice may have been omitted from guidelines. The recommendations from NICE were generic, potentially applicable to any care setting, encouraging interventions to be delivered by those with the right skills and competencies and ensuring continuity of care by one person undertaking an intervention, if possible. Therefore, we believe there should be a concerted effort to establish what the current role of community pharmacy is in signposting, link working and social prescribing to ensure guidelines reflect established practices. Existing evidence identified by this review did not clarify the value or importance of the pharmacist’s role in performing as a link worker by connecting people with services, thus the role could also be potentially undertaken by a pharmacy technician or counter assistant, expanding the scope of contribution by pharmacies. Further work is needed to examine the role of community pharmacy in social prescribing interventions, using a combination of pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and counter assistants.

This study demonstrates that community pharmacists have a diverse, adaptable skill set and a willingness to solve problems that go beyond medication. Although limited, there is evidence that pharmacists are involved in initiatives that are outside the dominant area of their professional expertise, speaking of the transformation of pharmacy — from dispensing shopkeepers to healthcare professionals at the heart of the community. This presents a contrast to existing disciplinary boundaries between pharmacists and other healthcare professionals, which indicated pharmacists take ownership of medication, rather than a holistic focus on the patient[27].

Multiple agencies working together and community support are key elements in models of social prescribing. Buy in and support from the healthcare-based referrers is vital for social prescribing to be successful[17]. Pharmacists are already involved in promoting public health through initiatives such as weight management and supporting people with sleep disorders, in addition to more established contributions in smoking cessation, cancer screening or sexual health, showing their potential to be involved in the wider care provision[38–44]. There is also increased focus on the role and potential of pharmacists to identify and support people with mental health conditions[45]. The current study suggests, although the evidence is limited, that community pharmacy may be moving towards a holistic care approach, an embedded part of primary healthcare and a focal point for biopsychosocial wellbeing, which is inclusive of physical, mental and social support.

Further translational studies with in-depth stakeholder feedback are needed to explore if social prescribing could be a vehicle to allow the blurring of disciplinary boundaries for the benefit of patients and, subsequently, society. Also, there may be considerations for educators to prepare the future pharmacy workforce to have readiness for adaptability for community involvement and care beyond the current professional characterisation around medicalised pharmaceutical care models. This could include further exploration of psychosocial aspects of health and wellbeing and interdisciplinary sessions with other healthcare professionals, such as occupational therapists and social workers.

Conspicuously absent from the literature is any work evaluating the financial or economic outcomes of community pharmacists’ involvement in social prescribing. This work is needed for community pharmacy business owners, policymakers and commissioners to recognise the monetary value of community pharmacy’s role in social prescribing initiatives. The limited evidence that is available demonstrates that pharmacists can contribute to the identification, link working and service delivery essential to social prescribing. However, this evidence is insufficient for service commissioning decision making. Future remuneration could potentially be via personalised health budgets, where the funding follows the patient. Personalised health budgets were initially piloted between 2009 to 2012 in around 70 primary care trusts and have since been implemented for people with long-term conditions[46–48].

However, to embrace the changing landscape of primary care, where multiagency and interdisciplinary team working and interdisciplinarity are the driving forces, community pharmacists and researchers may need to shift their focus to a bigger picture — one that encompasses the broader landscape of community and expanded roles of community pharmacists. There are wider discussions and considerations on a sustainable and contemporary model of funding for community pharmacy, but the profession itself can lead through demonstrating where the values, as well as the value, of community pharmacy can be.

Impact on policymakers

For policymakers, social prescribing is a tool for looking beyond biomedical parameters to positively affect the health and wellbeing of the nation and its widening health inequalities[11]. Yet, there has been no unified approach in how this is set out. As professionals with clinical expertise, pharmacists are underutilised in many aspects and this review suggests that the involvement of community pharmacies in social prescribing is currently limited despite the potential they offer[49–52].

Impact on practitioners

For social prescribing, the stated outcomes are improving physical and mental wellbeing, increasing community engagement and reducing social problems, such as loneliness. While this review did not provide strong evidence that community pharmacy was able to affect any of these metrics, there is a lack of strong evidence in other sectors also[7]. It is apparent from the literature, however, that the role of community pharmacy in social prescribing is poorly defined and not uniformly enacted. Users of social prescribing initiatives perceive value from a range of service providers; however, accessibility is not evenly distributed — it depends on the willingness of stakeholders in different regions to initiate[20,53–55]. In the context of improving person centredness, it would appear to be a missed opportunity to not explore the potential for community pharmacy to be included with a less peripheral role within the social prescribing policy and practice frameworks, as this may improve patient choice and reduce geographical accessibility variances.

Limitations

Keeping the search terms broad, focusing on the type of intervention, rather than a specific role in the intervention, may have led to the exclusion of some studies using specific wording. Terms such as navigator or link worker were not included in the search process and this may have led to exclusion of studies reporting on a specific function of pharmacist in social prescribing initiatives.

Assessing the quality of the studies was challenging. Authors often attempted to give details of the implementation of the social prescribing initiative, as well as its effectiveness, uptake and method of evaluation. This multiple focus in reporting did not lend itself well to a critical appraisal tool. Using established guidelines, such as GUIDED or SQUIRE, when reporting interventions would make comparison between initiatives easier[56,57]. Two of the included papers were not reported in a standard peer reviewed format, complicating appraisal further[31,32]. Future work evaluating social prescribing initiatives may be of better quality than currently published work, if researchers adopt a standardised approach to reporting evaluations of social prescribing interventions and outcomes.

Conclusion

We identified limited evidence documenting pharmacists’ involvement with social prescribing in the literature. Pharmacists can contribute in multiple ways and with a range of competencies around participant identification, referral to link workers, assessment and the direct delivery of interventions. As a profession, pharmacists can diversify roles and change workflows in response to community needs. Yet frequently, involvement seems to be on the side lines of funded mechanisms for social prescribing. There is a need for pharmacists to be an active partner in multidisciplinary dialogue to best articulate their ideal contribution. Future work should explore pathways to greater formalised involvement and funding streams to enable sustainable and collaborative non-medical support for community members with long-term conditions and pharmacists’ perceptions of this role expansion to aid implementation. By engaging in social prescribing, community pharmacy may be an agent of change by encouraging a culture shift, where the social capital of empowering individuals, families and communities is valued equally with monetary return.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the NSSR Team (including Jennie Popay, Lisa Arai, Nicky Britten, Mark Petticrew, Helen Roberts, Mark Rodgers, Amanda Snowden and Sally Baldwin) for providing Guidance on Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1Charles A, Ham C, Baird B, et al. Reimagining community services. London: : The King’s Fund 2018.

- 2Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. Department of Health. 2006.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-health-our-care-our-say-a-new-direction-for-community-services (accessed Jun 2021).

- 3Drinkwater C, Wildman J, Moffatt S. Social prescribing. BMJ 2019;:l1285. doi:10.1136/bmj.l1285

- 4Pescheny JV, Pappas Y, Randhawa G. Evaluating the Implementation and Delivery of a Social Prescribing Intervention: A Research Protocol. International Journal of Integrated Care 2018;18. doi:10.5334/ijic.3087

- 5Husk K, Blockley K, Lovell R, et al. What approaches to social prescribing work, for whom, and in what circumstances? A realist review. Health Soc Care Community 2019;28:309–24. doi:10.1111/hsc.12839

- 6Pescheny JV, Randhawa G, Pappas Y. The impact of social prescribing services on service users: a systematic review of the evidence. European Journal of Public Health 2019;30:664–73. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckz078

- 7Bickerdike L, Booth A, Wilson PM, et al. Social prescribing: less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013384. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013384

- 8NHS Long Term Plan. NHS England. 2019.https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk (accessed Jun 2021).

- 9Skingley A, Clift S, Hurley S, et al. Community singing groups for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: participant perspectives. Perspect Public Health 2017;138:66–75. doi:10.1177/1757913917740930

- 10Moffatt S, Steer M, Lawson S, et al. Link Worker social prescribing to improve health and well-being for people with long-term conditions: qualitative study of service user perceptions. BMJ Open 2017;7:e015203. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015203

- 11A connected society: a strategy for tackling loneliness. Laying the foundations for change. GOV.UK. 2018.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/a-connected-society-a-strategy-for-tackling-loneliness (accessed Jun 2021).

- 12Husk K, Elston J, Gradinger F, et al. Social prescribing: where is the evidence? Br J Gen Pract 2018;69:6–7. doi:10.3399/bjgp19x700325

- 13Just what the doctor ordered: social prescribing – a guide for local authorities. Local Goverment Association. 2016.https://www.local.gov.uk/publications/just-what-doctor-ordered-social-prescribing-guide-local-authorities (accessed Jun 2021).

- 14General Practice Forward View. NHS England. 2016.https://www.england.nhs.uk/gp/gpfv/ (accessed Jun 2021).

- 15Tierney S, Wong G, Roberts N, et al. Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: a realist review. BMC Med 2020;18. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-1510-7

- 16Buck D, Ewbank L. What is social prescribing? London: : The King’s Fund 2020.

- 17Wildman JM, Moffatt S, Penn L, et al. Link workers’ perspectives on factors enabling and preventing client engagement with social prescribing. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:991–8. doi:10.1111/hsc.12716

- 18Joint review of partnerships and investment in voluntary, community and social enterprise organisations in the health and care sector. GOV.UK. 2016.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/review-of-partnerships-and-investment-in-the-voluntary-sector (accessed Jun 2021).

- 19Taylor DA, Nicholls GM, Taylor ADJ. Perceptions of Pharmacy Involvement in Social Prescribing Pathways in England, Scotland and Wales. Pharmacy 2019;7:24. doi:10.3390/pharmacy7010024

- 20Baird B, Cream J, Weaks L. Commissioner perspectives on working with the voluntary, community and social enterprise sector. London: : The King’s Fund 2018.

- 21Standards for pharmacy professionals. General Pharmaceutical Council. 2017.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017_0.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 22South J, Higgins TJ, Woodall J, et al. Can social prescribing provide the missing link? PHC 2008;9:310. doi:10.1017/s146342360800087x

- 23Donovan GR, Paudyal V. England’s Healthy Living Pharmacy (HLP) initiative: Facilitating the engagement of pharmacy support staff in public health. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2016;12:281–92. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.05.010

- 24Lindsey L, Husband A, Steed L, et al. Helpful advice and hidden expertize: pharmacy users’ experiences of community pharmacy accessibility. J Public Health Published Online First: 2 September 2016. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdw089

- 25Guidance on the Medicines Use Review service. Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. 2012.http://archive.psnc.org.uk/data/files/PharmacyContract/Contract_changes_2011/MUR_guidance_Sept_2012.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 26Stewart D, Whittlesea C, Dhital R, et al. Community pharmacist led medication reviews in the UK: A scoping review of the medicines use review and the new medicine service literatures. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2020;16:111–22. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.04.010

- 27Jamie K. The pharmacy gaze: bodies in pharmacy practice. Sociol Health Illn 2014;36:1141–55. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12157

- 28Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- 29Elm E von, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ 2007;335:806–8. doi:10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.ad

- 30Dayson C, Bennett E. Evaluation of Doncaster Social Prescribing Service: understanding outcomes and impact. Sheffield Hallam University 2016.

- 31Evaluation of GO Active, Get Healthy. Oxfordshire Sport and Physical Activity. 2019.https://www.activeoxfordshire.org/uploads/evaluation-of-go-active-get-healthy.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 32An integrated community development approach to health and wellbeing of older people: sharing our learning. Mid and East-Antrim Agewell Partnership. 2019.https://dunhillmedical.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/19-06-19-IMPACTAgewell-proof-of-concept.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 33Marshall OBE S, Crampton J. Making connections – reducing loneliness and encouraging well-being. Working with Older People 2015;19:182–7. doi:10.1108/wwop-09-2015-0025

- 34Murphy AL, Gardner DM, Martin-Misener R, et al. Partnering to enhance mental health care capacity in communities. Can Pharm J 2015;148:314–24. doi:10.1177/1715163515607310

- 35Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster University. 2006.https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 36Parker R, Brooks W, Wright J, et al. Community Partners Join Forces: Battling Obesity and Diabetes Together. J Community Health 2016;42:344–8. doi:10.1007/s10900-016-0260-0

- 37Community pharmacies: promoting health and wellbeing. NICE guideline [NG102]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2018.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng102 (accessed Jun 2021).

- 38Morrison D, McLoone P, Brosnahan N, et al. A community pharmacy weight management programme: an evaluation of effectiveness. BMC Public Health 2013;13. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-282

- 39Evans G, Wright D. Long-Term Evaluation of a UK Community Pharmacy-Based Weight Management Service. Pharmacy 2020;8:22. doi:10.3390/pharmacy8010022

- 40Hanes CA, Wong KKH, Saini B. Clinical services for obstructive sleep apnea patients in pharmacies: the Australian experience. Int J Clin Pharm 2014;36:460–8. doi:10.1007/s11096-014-9926-9

- 41Cawley MJ, Warning WJ II. A systematic review of pharmacists performing obstructive sleep apnea screening services. Int J Clin Pharm 2016;38:752–60. doi:10.1007/s11096-016-0319-0

- 42Brown TJ, Todd A, O’Malley C, et al. Community pharmacy-delivered interventions for public health priorities: a systematic review of interventions for alcohol reduction, smoking cessation and weight management, including meta-analysis for smoking cessation. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009828. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009828

- 43Lindsey L, Husband A, Nazar H, et al. Promoting the early detection of cancer: A systematic review of community pharmacy-based education and screening interventions. Cancer Epidemiology 2015;39:673–81. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2015.07.011

- 44Gudka S, Afuwape FE, Wong B, et al. Chlamydia screening interventions from community pharmacies: a systematic review. Sex Health 2013;10:229. doi:10.1071/sh12069

- 45El-Den S, McMillan SS, Wheeler AJ, et al. Pharmacists’ roles in supporting people living with severe and persistent mental illness: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2020;10:e038270. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038270

- 46Evaluation of the personal health budget pilot programme. Personal Health Budgets Evaluation. 2012.https://www.york.ac.uk/inst/spru/research/pdf/phbe.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 47Personal Health Budgets: Implementation following the national pilot programme; overall project summary. Working Paper 2949. PHBE. 2019.https://www.pssru.ac.uk/pub/5433.pdf (accessed Jun 2021).

- 48Alakeson V, Boardman J, Boland B, et al. Debating personal health budgets. BJPsych Bull 2016;40:34–7. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.114.048827

- 49Saramunee K, Krska J, Mackridge A, et al. How to enhance public health service utilization in community pharmacy?: General public and health providers’ perspectives. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 2014;10:272–84. doi:10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.05.006

- 50Edwards RA. Pharmacists as an Underutilized Resource for Improving Community-Level Support of Breastfeeding. J Hum Lact 2013;30:14–9. doi:10.1177/0890334413491630

- 51Latif A, Waring J, Watmough D, et al. ‘I expected just to walk in, get my tablets and then walk out’: on framing new community pharmacy services in the English healthcare system. Sociol Health Illn 2018;40:1019–36. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12739

- 52Altman IL, Mandy PJ, Gard PR. Changing status in health care: community and hospital pharmacists’ perceptions of pharmacy practice. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice 2018;27:249–55. doi:10.1111/ijpp.12505

- 53Beardmore A. Working in social prescribing services: a qualitative study. JHOM 2019;34:40–52. doi:10.1108/jhom-02-2019-0050

- 54Heijnders ML, Meijs JJ. ‘Welzijn op Recept’ (Social Prescribing): a helping hand in re-establishing social contacts – an explorative qualitative study. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2017;19:223–31. doi:10.1017/s1463423617000809

- 55Redmond M, Sumner RC, Crone DM, et al. ‘Light in dark places’: exploring qualitative data from a longitudinal study using creative arts as a form of social prescribing. Arts & Health 2018;11:232–45. doi:10.1080/17533015.2018.1490786

- 56Duncan E, O’Cathain A, Rousseau N, et al. Guidance for reporting intervention development studies in health research (GUIDED): an evidence-based consensus study. BMJ Open 2020;10:e033516. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033516

- 57Davidoff F, Batalden P, Stevens D, et al. Publication guidelines for quality improvement in health care: evolution of the SQUIRE project. Quality and Safety in Health Care 2008;17:i3–9. doi:10.1136/qshc.2008.029066