AIM

• To investigate (i) the feasibility and acceptability to pharmacists of a supervised self administration of methadone service in community pharmacies in East London and City Health Authority and (ii) patient compliance.

DESIGN

• Collection of data on patient compliance and behaviour, and self-completion questionnaires for pharmacists at start and end of study period.

SUBJECTS AND SETTING

• Selected community pharmacists and methadone patients in City and East London Health Authority.

OUTCOME MEASURES

• Patient compliance and adherence to patient agreement within pharmacies, attitudes towards service provision before and after study period, contact with prescribers and police.

RESULTS

• There was a high level of compliance with prescribed supervised doses of methadone. Pharmacists

reported few serious incidents. Contact with prescribers related mainly to prescription-related issues. Contact with police was minimal and did not change significantly after the introduction of the supervised administration of methadone service. Pharmacists had some concerns about support available to them, and these were similar at the end of the study. Pharmacists became more positive about the contribution they could make to treatment.

CONCLUSION

• From the pharmacists’ perspective, the supervised self-administration of methadone service was introduced to East London and City Health Authority in a relatively trouble-free manner. Pharmacists reported few problems with patients and compliance with supervised doses was high.

Most methadone prescribed in England is dispensed as take-home doses and there have been concerns about the diversion of prescribed methadone on to the illicit market[1]. This may have been implicated, in some cases, in the deaths of opiate-naive individuals, especially children[2].

Furthermore, a study from Australia has indicated that there is an increased risk of “fatal accidental drug toxicity” for patients during the first two weeks on methadone when compared with heroin users not in treatment[3].

Supervised self-administration of methadone (SSAM) services have been reported to exist in Wales from 1991[4] and in Glasgow since the mid 1990s[5]. In Scotland, Matheson et al report that 33 per cent of community pharmacies in Scotland in 1995 provided, or were willing to provide, an SSAM service[6] and, in 1998, 95 per cent of prescriptions for methadone in Glasgow called for supervision[7]. Until recently, formalised service provision has not been available in England.

However, in 1999 the Government took on board concerns about take-home supplies of methadone and the 1999 clinical guidelines for the management of drug misuse have recommended that most patients new to methadone treatment should have their methadone consumption supervised

for the first three months of treatment[8]. This recommendation has led many local drug misuse treatment services to commence discussions around the feasibility of providing SSAM services at community pharmacies where they have not already been implemented. Previous research in the

late 1990s indicated that there were at least 20 health authorities providing a degree of SSAM around the country, with 33 health authorities planning this for the future[9].

The Department of Health has recognised community pharmacists as key partners in providing this service[8] and around two-fifths of community pharmacists in Britain believe that SSAM is an appropriate role for the community pharmacist[10,11]. Furthermore, almost 60 per cent of pharmacists in a Scottish survey believed that SSAM prevents the diversion of illicit drugs.10

In 1998 a decision was taken to phase in the introduction of an SSAM service to the East London and City Health Authority. This was part of the “Methadone prescribing through primary care” shared care

scheme — a scheme in which more than 50 per cent of general practitioners are prescribing methadone (Pursey, personal communication). East London and City HA is a health authority in the east of London, with a high level of social deprivation (Jarman score of 6812 ) and a large ethnic mix. The

problems of drug misuse in the locality are sizeable and varied. Although SSAM services have been successfully piloted elsewhere in London[13] a phased introduction of SSAM to East London and City HA was proposed, because the service structure differed in a number of ways from that in the Luger et al study[13]. The initial phase was known as Phase 1, and would be followed by Phase 2. Phase 2 would

increase the availability of SSAM services, based on the evaluation report for Phase 1. Part of the evaluation of Phase 1 will be reported in this paper. The evaluation included a study of the feasibility and acceptability of the service, and the views of pharmacists, staff at drug agencies and clients involved in

the service. This paper describes: pharmacist and pharmacy demographics, patient compliance, problems with the scheme, and pharmacists’ views on the service.

METHODS AND DATA COLLECTION

Recruitment of pharmacies

Pharmacists were asked to express their interest in taking part in the study via their local pharmaceutical committee using an “expression of interest form”. The form included a requirement for past experience of daily dispensing. The health authority had further selection criteria, which included location and ability to provide some degree of privacy. All interested pharmacies were visited to assess the suitability of their premises. Screens were offered to pharmacies by the health authority for use in

pharmacies where needed. This resulted in a small number of pharmacies (N=32) being selected to take part in the Phase 1.

Protocols

Protocols for service provision were drawn up by the “Methadone prescribing through primary care” steering group. With regard to the prescribing and dispensing of methadone, prescriptions for SSAM were to be written on either the FP10(MDA) form from GPs or on the FP10(HPad) form from drug clinics, and were to include the instruction “to be supervised”. The pharmacist was contacted by the prescriber or key worker and asked if they could take on a new patient. Pharmacists were instructed to supervise doses of methadone for patients each day the pharmacy was open, unless a client was intoxicated or had missed three or more consecutive doses. In either case, the pharmacist would withhold that day’s methadone dose and contact the prescriber or key-worker so that the patient could be assessed before the dose was dispensed.

Compliance and problems

For the purposes of the evaluation, community pharmacists were required to keep certain records in

order that the service could be audited and monitored in terms of patient compliance with dosing regimens, and any problems which arose as a result of the service. The following forms were used:

“New patient accepted” form Used at the start of a patient’s participation in SSAM, the “New patient accepted” form was completed by the pharmacist. It recorded the pharmacist’s name and the name and address of the pharmacy, a patient identifier (initials, date of birth, first part of postcode), the prescriber’s and key worker’s names, the date on which supervision began, and the starting dose.

On completion of treatment, or removal of a patient from the SSAM service, the final section of this form was completed, recording the date on which the supervision terminated.

Supervision sheets

Supervision sheets were used by the pharmacist daily for each patient, recording the time each day a supervised dose occurred over a two-week period (Monday to Saturday). Space was also allocated to note if other issues occurred, including when supervision was refused because: the patient was intoxicated; the patient had missed three or more consecutive doses; the patient’s behaviour was unacceptable; there had been prescriber/pharmacist contact; or there had been police/pharmacist contact. In such instances the pharmacist was asked to tick the appropriate box and complete an incident report form (see below).

Incident report form

The incident report form was used to record incidents that occurred during SSAM. Pharmacists were asked to tick an option which best described the incident and then provide further details of what occurred in the space provided. They also noted the client’s ID, the date, the pharmacy name and the pharmacist’s name.

Views and activities of service-providing pharmacists

Views of pharmacists, pharmacy demographics and the occurrence of incidents within the pharmacy were collected using a self-completion questionnaire at the start and completion of the evaluation period. The questionnaire was based on one previously piloted and used in two other SSAM pilot studies. Attitude statements had been developed from interviews with pharmacists in previous pilots, questionnaires used in previously unpublished service development work and discussions with experts. The questionnaire was administered before Phase 1 to pharmacists attending the service-specific training day. At the end of Phase 1, pharmacists were posted a questionnaire, and non-responders were

followed up after four weeks. Pharmacists were requested to provide their opinions on a range of issues using a five-point Likert scale: “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Neither agree nor disagree”, “Disagree” and “Strongly disagree”. There was also a box to tick if the statement was not applicable to the pharmacist at the start of Phase 1. Data are reported for pharmacists “active” during Phase 1.

Results

As of 30 November 2000, 172 individual patients had been referred for SSAM from a number of drug agencies and GPs (as part of the “Methadone prescribing through primary care” scheme) for a total of 199 treatment episodes. (If a patient who had been issued with a “New patient accepted” form dropped out of the scheme, but subsequently returned, and was issued with a new form, this counted as two treatment episodes.) However, it should be noted that the full complement of paperwork was held on only 173 of these episodes. The shortfall consisted of patients for whom no “New patient accepted” form was issued, or whose supervision details were incomplete, or both.

It is possible that there were, in fact, more prescribing sites than outlined above — during the final stages of data collection, pharmacists and key workers made reference to other prescribing sites, although no record had been noted on “New patient accepted” forms.

Community pharmacy and pharmacist demographics

Of the 32 pharmacies originally signed up to provide this service, 21 (65.9 per cent) provided data on supervised patients, although in one case the data provided were almost entirely incomplete. Of the remaining 11 pharmacies, three had not seen any patients and eight (25 per cent) had patients for whom they had supervised the administration of methadone, but for whom they had completed no paperwork. Self-reported reasons for non-completion of paperwork included:

- No knowledge of the required paperwork

- Chose not to complete the paperwork

- Chose to provide the service, but not to complete the paperwork (of these, one believed the payment for supervision was being included by the pricing authorities)

Personal and professional experience and service provision

The mean number of years pharmacists had been qualified was 19 (SD=9.6; range 1–43). The mean time they had worked in a community pharmacy was 18 years (SD=10; range 1–43). The majority of the pharmacies were independents (61 percent) and 68 percent were located in a small group of local shops.

Experience of dispensing and supervised methadone consumption

Over half (58 percent) of the pharmacists had never been requested to supervise the consumption of methadone in the pharmacy. The mean number of methadone patients normally provided with a methadone dispensing service in any one week (as estimated by data from pharmacist questionnaires completed at the start of the evaluation) was 12.6 (SD=11.5; median 8; interquartiles 4.8, 17; range 1–40). This had increased to 12.8 (SD=14.4; median 7; interquartiles 2.5, 16; range 1–50) at the end of Phase 1 (not significant at the 5 percent level).

Numbers of supervised patients per pharmacy

The average number of supervised patients per pharmacy was 9.48 (SD=9.83; median 5; interquartiles 5, 14; range 1–39, N=21). Nine patients had changed pharmacy and 14 had more than one episode of

SSAM at the same pharmacy.

Compliance rates

“Days of missed supervision” was defined as either: (i) the patient did not attend the pharmacy to be supervised on days when supervision had been described, or (ii) the patient attended the pharmacy for supervision, but was refused methadone on days where supervision had been prescribed (ie, excluding bank holidays and days when the pharmacy was closed).

The overall compliance rate for prescribed supervised methadone doses for the duration of the evaluation period was 90.3 percent. The mean number of days of prescribed supervised doses per patient was 38.7 days (SD=36.4; median 24; interquartiles 11, 58.5; range 1–152). The modal number of

days was 6. On average, patients missed 3.8 days (SD=5.4; median 2; interquartiles 0,5; range 0–35), with the modal number of missed supervised days = 0.

Incidents and problems in the pharmacy

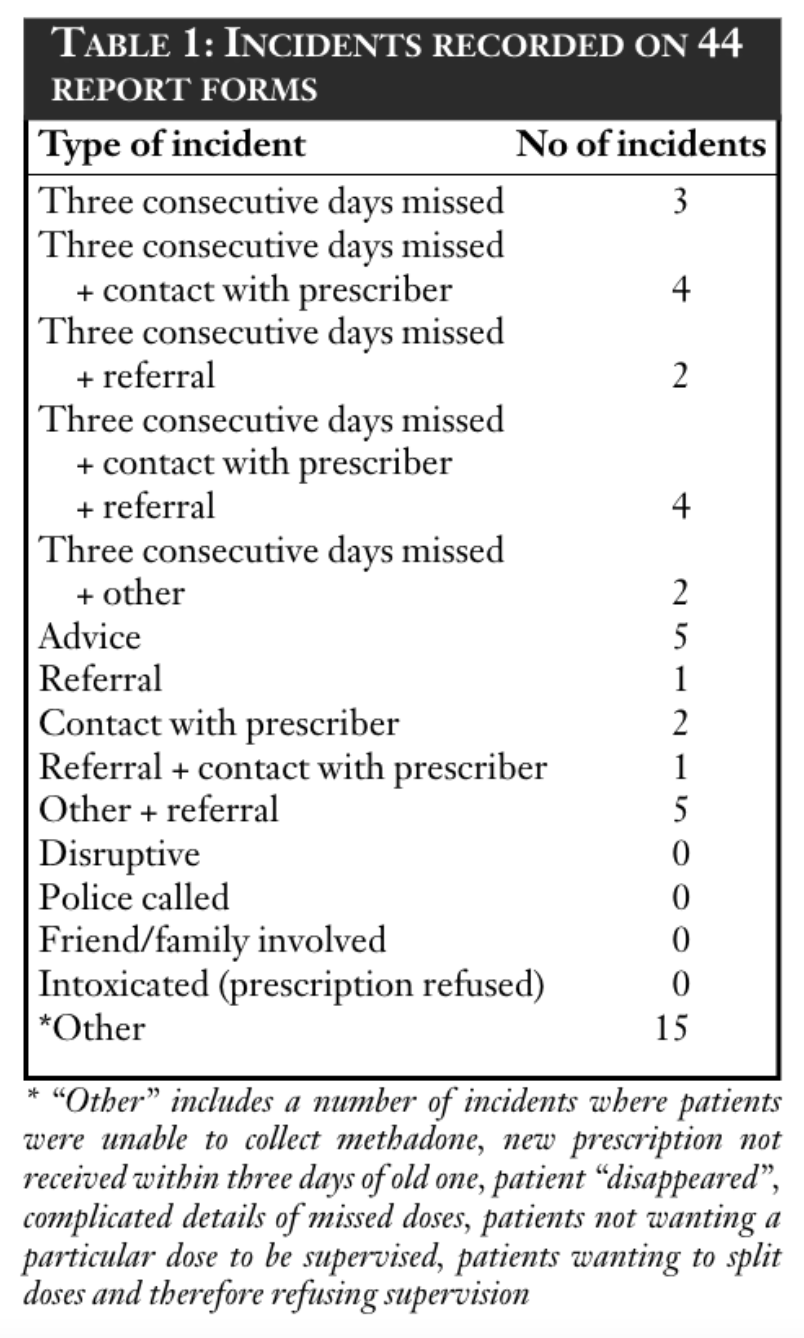

A total of 66 completed incident report forms were received dated up to and including 30 November 2000. However, only 44 of these related to patients included in the analysis. Results are reported in Table 1.

An incident report form was not always received for an incident which had been noted by the pharmacist on the supervision sheet. Similarly, some supervision sheets indicated that three consecutive days were missed, but no record was made of “contact with the prescriber”, “refusal to dispense” or whether the incident report form was completed. It is possible that pharmacists were complying with protocols to contact prescribers in such instances, but were failing to complete the relevant records.

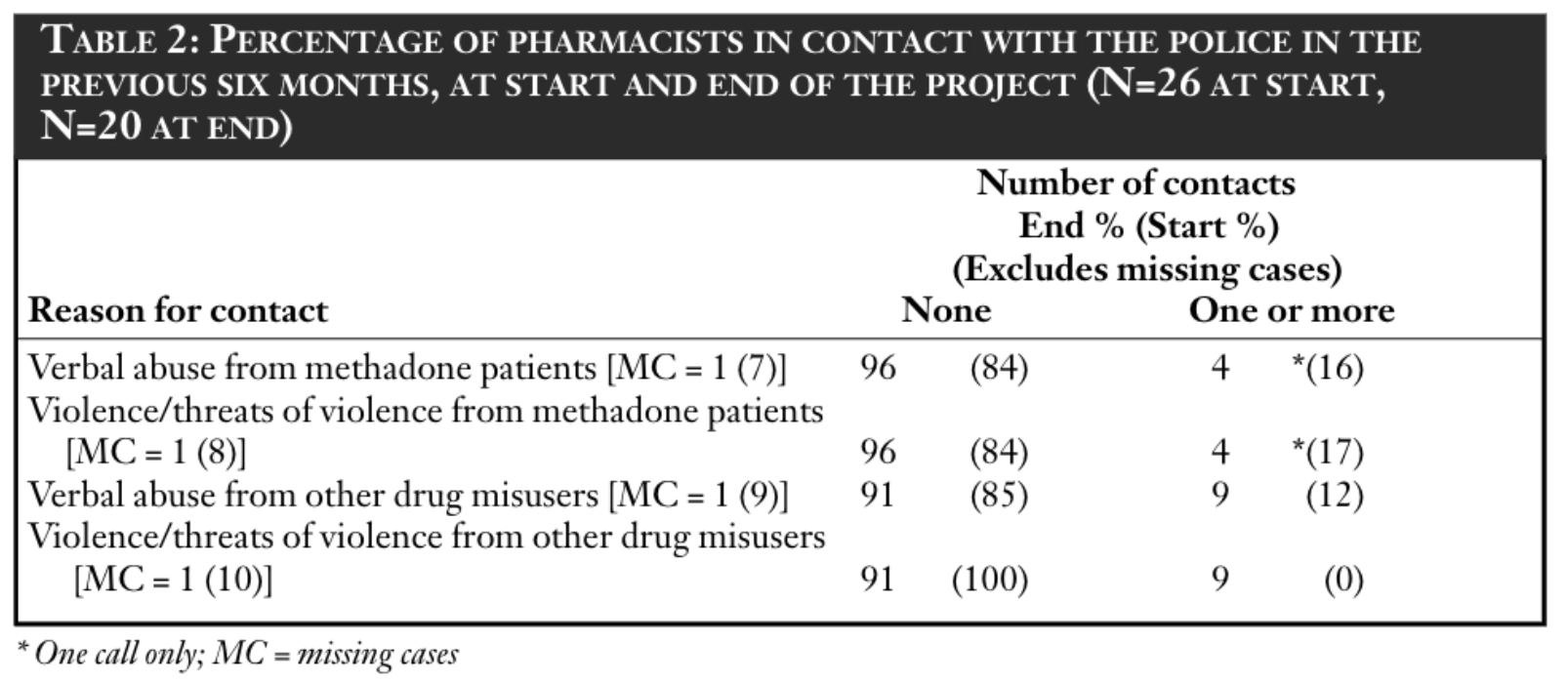

Problems reported by pharmacists in “before” and “after” questionnaires

Pharmacists were asked about their contact with the police during the previous six months, at the start and at the end of Phase 1. Four categories were given: two related specifically to methadone patients and two related to other drug misusers. Results are reported in Table 2.

Overall, most responding pharmacists had not had to contact the police during the six months before the commencement of Phase 1. A minority had to do so only once during this time and this was similar at the end of Phase 1.

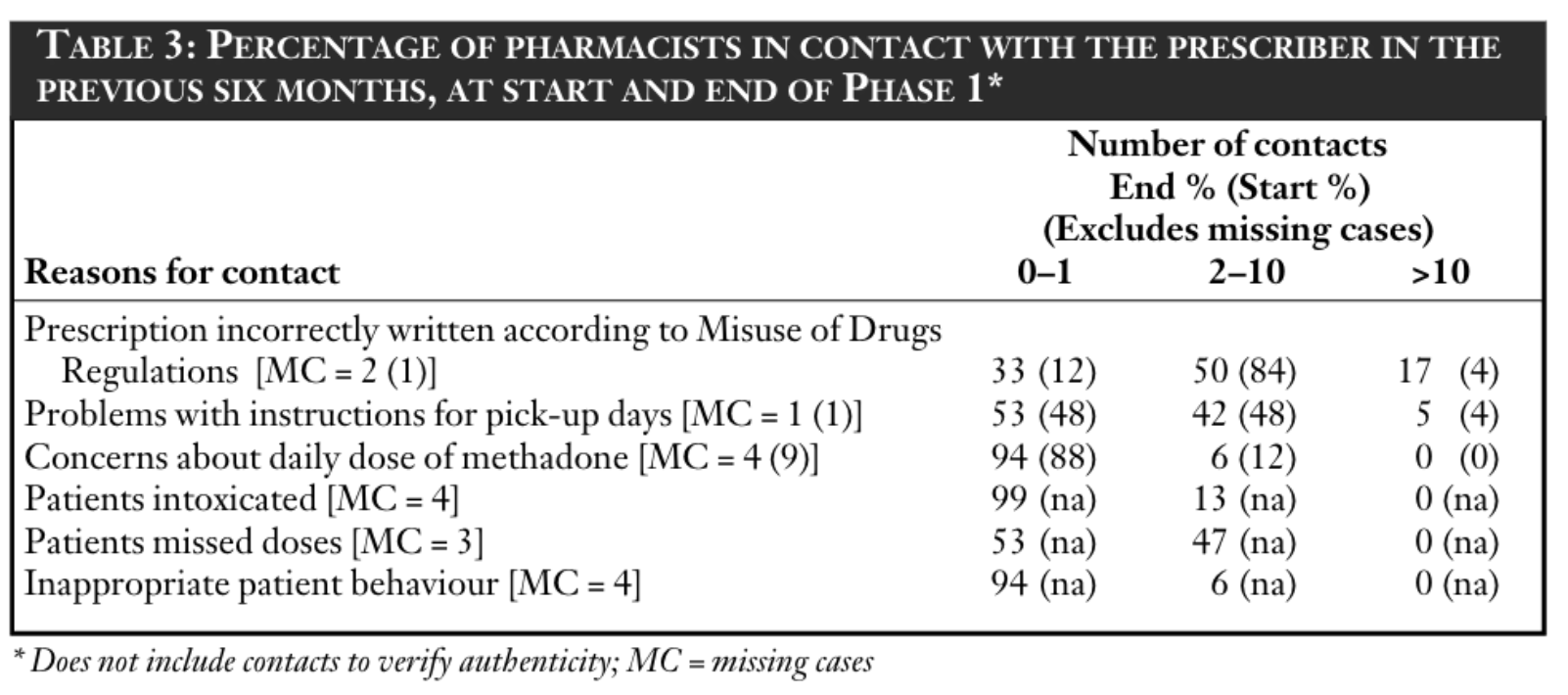

Contact with the prescriber

Both before and at the end of Phase 1, pharmacists were asked about their contact with prescribers during the previous six months (excluding times when they contacted the prescriber to verify the authenticity of a prescription). Results are reported in Table 3. Contacts with prescribers most frequently related to incorrectly written prescriptions which could not be dispensed due to legal restrictions under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 1985. A number of contacts also related to problems with instructions concerning instalments. However, it was rare for pharmacists to query doses. There was little change at the end of Phase 1. Most pharmacists reported little contact with the prescriber during the previous six months because clients were intoxicated or because of inappropriate behaviour.

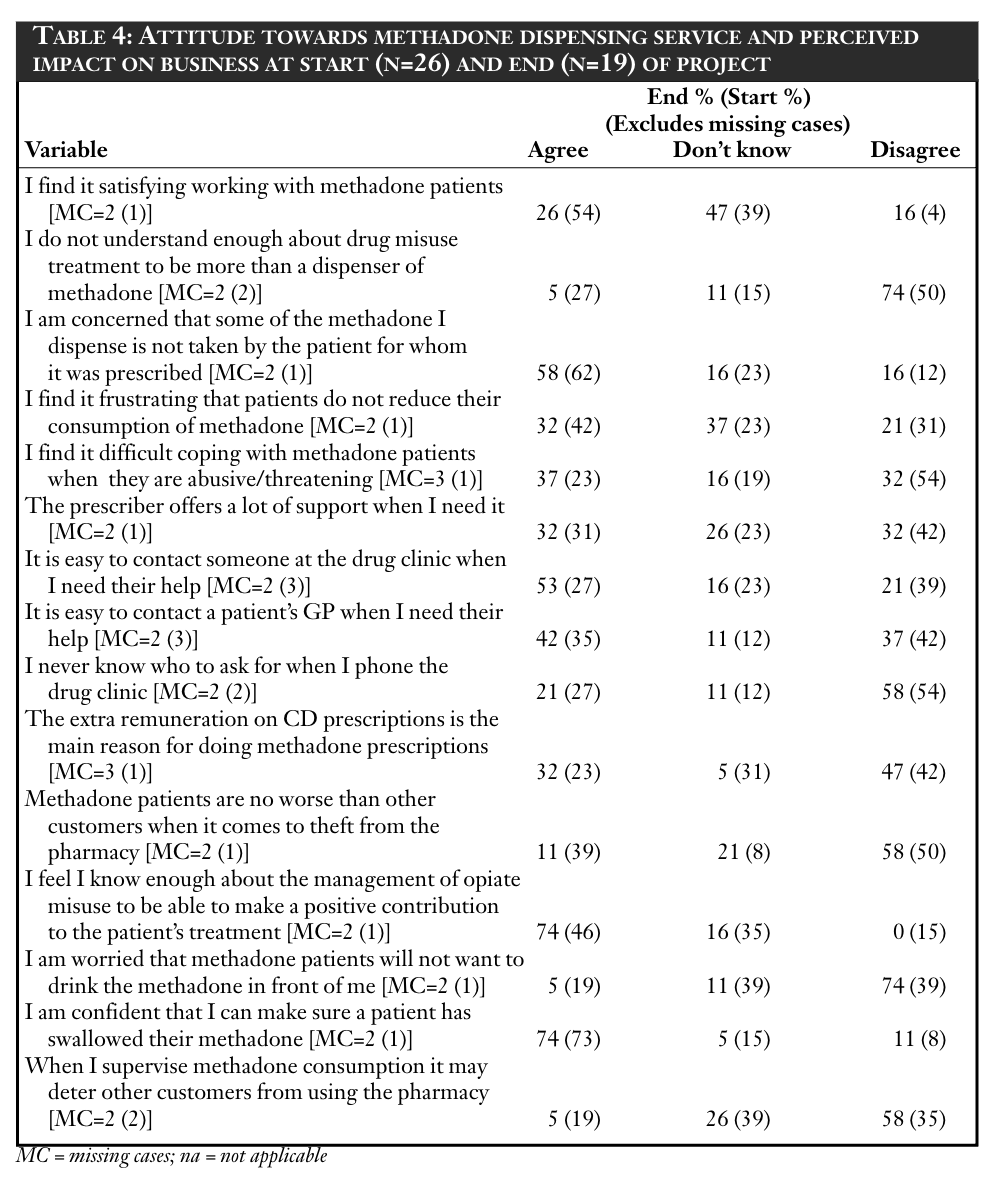

Pharmacists’ attitudes

Pharmacists’ attitudes are presented in Table 4 (“strongly agree” and “agree” have been combined as have “strongly disagree” and “disagree”). A statistical comparison of the “before” and “after” data was made by combining “strongly disagree” and “disagree” and comparing with all other data for that variable using a chi-squared test, and by combining “strongly agree” and “agree” and comparing with all other data for that variable using a chi-squared test.

Only two variables revealed significant test results. Respondents disagreed more with the statement “I am worried that methadone clients will not want to drink the methadone in front of me” at the end of the evaluation period (40 per cent before versus 82 per cent after, χ2 =7.41, df=1, P<0.005). Respondents agreed more with the statement “I feel I know enough about the management of opiate misuse to be able to make a positive contribution to the patient’s treatment” at the end of the evaluation period (48 per cent before versus 82 per cent after; χ2 =5.06, df=1, P<0.05).

DISCUSSION

It appears that, from the pharmacists’ perspective, SSAM was introduced to East London and City HA in a relatively trouble-free manner. Pharmacists reported few problems with patients.

Data on patient compliance with prescribed supervised doses was high overall at 90.0 percent for those patients for whom there were complete data. Incomplete data for patients, where there were large gaps in reported supervision, had been removed from the calculations. It is unlikely that gaps

of one week or more would comprise “missed doses” as defined in this evaluation period and it is more likely that such large gaps could be attributed to either (i) patients dropping out of treatment, (ii) failure of pharmacists to complete data or (iii) failure of East London and City HA to pass paperwork on to the evaluation team. However, it is possible that such data may, in some cases, be representative of a few chaotic individuals for whom SSAM was not appropriate.

Although pharmacists reported few problems, the data from the “Incident Report Forms” should be interpreted with caution, since they probably under-report the incidence of problems in the pharmacy such as disruption, verbal abuse and shoplifting. This caveat is supported by data from the “after” Phase 1 questionnaire, which revealed that the police had been called on account of threats of violence and verbal abuse (albeit only once for each problem type) and by the fact that, in informal discussion with pharmacists during the evaluation period, anecdotal reports were received of minor disruption caused by clients which had not been noted on forms.

Other studies have shown that such patient behaviour is a barrier to service provision11,14,15 and may be a barrier to more pharmacists becoming involved. However, experience from Scotland has shown that pharmacists are willing to take this service on board 6 and that active support from professional bodies and health authorities may encourage pharmacists to take part in an extended role with regard to services for drug misusers. 16

There had been an expectation that contact with prescribers and key workers might alter during the evaluation period. Data indicated that pharmacists made frequent contact with GPs regarding incorrectly written prescriptions and problems with instalment instructions and the number of contacts did not diminish during Phase 1. Such problems are not particular to SSAM services and there remain issues for training GPs with regard to correct writing of prescriptions and for a possible review of the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 1985 (as suggested by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s working party report17 ) in order to allow pharmacists a certain degree of professional discretion.

Pharmacists, however, made fewer contacts with regard to patient behaviour and well-being than contacts due to prescription problems. Most pharmacists had contacted a doctor once at the most concerning patients who were intoxicated or behaving inappropriately. However, nearly half had contacted the prescriber twice or more with regard to missed doses.

The data in this study suggest that, from a pharmacy perspective, SSAM has been a feasible and suitable service to offer. This echoes findings from Luger et al,13 who noted that SSAM was workable for pharmacists and that all pharmacists agreed to continue to provide the service. They also noted, however, that from the patient perspective there were issues such as lack of privacy13 and that these concerns have also been noted among Scottish patients.18 Issues surrounding patient privacy have been explored in the evaluation of Phase 1 of SSAM and will be reported elsewhere. However, it may

be important to note at this point that East London and City HA pharmacists did not appear to have the same level of awareness or concerns about privacy as did their patients.

It is likely that SSAM will continue to be the method of dispensing methadone for many new patients to East London and City HA and that it will become the norm in many other parts of the UK, in line with

Government guidelines.8 This study has found further evidence to support the acceptability of SSAM as a service from a community pharmacy perspective. However, the data should be interpreted with a degree of caution — both this study and that of Luger et al13 were conducted in areas of Central London, and there may be local issues around demography, local drug misuse issues, availability of

services and access to them, which may make generalisations of success unsound.

Furthermore, the views of patients and possibly of other pharmacy users need to be borne in mind when setting up an SSAM service.

This paper was accepted for publication on 12 November 2001.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This project was supported with funding from East London and City Health Authority. We thank Helen Clark (commissioning manager, substance misuse, East London and City HA), Kieran Burke (shared care co-ordinator, East London and City HA), participating pharmacists, drug agency staff and patients for their support.

REFERENCES

- Strang J, Sheridan J, Barber N. Prescribing injectable and oral

methadone to opiate addicts: results from the 1995 national

postal survey of community pharmacies in England and Wales.

BMJ 1996;313:270–2. - Binchy JM, Molyneux EM, Manning J. Accidental ingestion of

methadone by children in Merseyside. BMJ 1994;308:1335–6. - Caplehorn JR, Drummer OH. Mortality associated with New

South Wales methadone programs in 1994: lives lost and saved.

Med J Austral 1999;170:104–9. - McBride AJ, Mali I, Atkinson R. Supervised administration of

methadone by pharmacists. BMJ 1994;309:1234. - Scott RT, Burnett SJ, McNutty H. Supervised administration of

methadone by pharmacists. BMJ 1994;308:1438. - Matheson C, Bond CM, Hickey F. Prescribing and dispensing for

drug misusers in primary care: current practice in Scotland. Fam-

ily Practice 1999;16:375–9. - Roberts K. Update on methadone supervision figures. Pharm J

1998;260:703. - Departments of Health. Drug Misuse and Dependence: Guide-

lines on Clinical Management. London: The Stationery Office;

1999. - Cairns C, Hender J. Community pharmacy supervised

methadone administration schemes in the UK. London: Pharma-

cy Academic Practice Unit, St George’s Hospital; 1999. - Matheson C, Bond CM, Mollison J. Attitudinal factors associated

with community pharmacists’ involvement in services for drug

misusers. Addiction 1999;94:1349–59. - Sheridan J, Strang J, Taylor C, Barber N. HIV prevention and

drug treatment services for drug misusers: a national study of

community pharmacists’ attitudes and their involvement in ser-

vice specific training. Addiction 1997;92:1737–48. - National Register of Jarman Indices, Yearly Report. London:

Imperial College; 1999. - Luger L, Bathia N, Alcorn R, Power R. Involvement of commu-

nity pharmacists in the care of drug misusers: pharmacy-based

supervision of methadone consumption. Int J Drug Policy

2000;11:227–34. - Matheson C, Bond C. Motivations for and barriers to community

pharmacy services for drug misusers. Int J Pharm Pract

1999;7:256–63. - Sheridan J, Strang J, Barber N, Glanz A. Role of community

pharmacies in relation to HIV prevention and drug misuse: find-

ings from the 1995 national survey in England and Wales. BMJ

1996;313:272–4. - Jones P, van Teijlingen E, Matheson C, Gavin S. Pharmacists’

approach to harm minimisation initiatives associated with

problem drug use: the Lothian survey. Pharm J 1998;260:

324–7. - Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Report of the

Working Party on Pharmaceutical Services for Drug Misusers.

Report to the Council of the Society. London: The Society; 1998. - Matheson C. Privacy and stigma in the pharmacy: illicit drug

users’ perspectives and implications for pharmacy practice.

Pharm J 1998;260:639–41