This content was published in 2012. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

Abstract

Aim

To explore the experiences of pharmacists in supplying unlicensed medicines for children

Design

Online questionnaire survey

Subjects and setting

Members of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Local Practice Forum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society

Results

The questionnaire was electronically delivered to 1,551 members and 40 replies were received (response rate 2.6%). 34 respondents (85%) were aware of children prescribed an unlicensed medicine and 22 of these were aware of families who had experienced problems obtaining a further supply. Melatonin, omeprazole and spironolactone were the top three problem medicines highlighted. The most common problems were GPs unfamiliar with the medicine, not being willing or able to prescribe and prescribing errors; parents not informing their GP in time to generate a prescription or their community pharmacist in time to obtain further supplies before they ran out; the price of unlicensed medicines and short shelf lives. Communication between sectors and education of parents were highlighted as key to minimising problems and disruptions to treatment for patients transferring between different care settings.

Conclusions

Unlicensed medicines continue to cause problems for families, pharmacists and doctors in hospital and community. Pharmacists in all sectors have an important role in ensuring that these medicines are used only when essential, advising prescribers on alternatives where available, educating families and purchasing responsibly with due regard to timeliness of supply, quality assurance, bioequivalence and cost.

The use of unlicensed and off-label medicines for children is both necessary and common due to a lack of suitable neonatal and paediatric formulations and prescribing information for many drugs. Numerous studies have been conducted in the UK and around the world showing the incidence and nature of this issue. Up to two thirds of children in European hospitals, 90 per cent of babies in neonatal intensive care and 11 per cent of UK children prescribed medicines by their GP receive unlicensed and off-label (medicines used outside the terms of their licence) medicines.1–3 The use of these drugs has been associated with adverse drug reactions4–6 and more recently with an increased risk of medication errors.7

It must be remembered that unlicensed medicines have not been assessed by the regulatory authorities for safety, efficacy and quality in the same way that licensed medicines have. Prescribing and supplying unlicensed medicines is potentially more risky than using licensed medicines and therefore should only be done when a suitable licensed product that meets the needs of the patient is unavailable. Guidance for prescribers of, and pharmacists supplying, unlicensed medicines has been issued detailing responsibilities of all concerned.8–11

EU legislation passed in 2007 promises to improve the situation and requires the pharmaceutical industry to study drugs in children and produce appropriate formulations.12 Incentives are in place to encourage this. It is, however, likely to take many years to resolve the daily problems faced by paediatric doctors, GPs, nurses, pharmacists and families.

Despite many studies describing the extent and nature of unlicensed and off-label medicines use in children, few studies have explored GPs’, community pharmacists’ and families’ experiences. One study from a specialised UK children’s hospital showed that one third of families had difficulty obtaining these medicines in primary care and that this could cause treatment disruption.13

A questionnaire survey in Northern Ireland showed that 93 per cent of community pharmacists were familiar with the term “unlicensed”.14 Most had first become familiar with the issue during their undergraduate studies. One third reported dispensing unlicensed and off-label medicines in the four weeks before the questionnaire survey.

We wished to find out the experiences of pharmacists in our own Royal Pharmaceutical Society local practice forum.

Method

Pharmacist members of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Local Pharmacy Forum were contacted by the RPS on behalf of the researchers and asked to respond to a brief online questionnaire regarding their experiences of providing further supplies of unlicensed medicines. Members were asked to respond to the questions (see Panel “Questions asked”) and were given two weeks to respond. The results (all anonymous) were sent in an Excel spreadsheet by the RPS to the study team, who carried out a content analysis on the data.

Panel: Questions asked

- Do you know of families with children who have been discharged from hospital on an unlicensed medicine

- Are you aware of any of them experiencing problems when trying to obtain a further supply of these medicines?

- If so what problems are you aware of?

- How were these problems resolved?

- What are the most common unlicensed medicines which cause problems and why?

- Do you have any suggestions on how things could be improved?

- Is there anything else that you would like to add?

Results

The questionnaire was electronically delivered to 1,551 members of the LPF and 40 replies were received (response rate 2.6 per cent). Thirty-four respondents (85 per cent) were aware of children who had been discharged from hospital on an unlicensed medicine and 22 of these were aware of families who had experienced problems obtaining a further supply. The main problems experienced by respondents are summarised below.

Issues relating to GPs

Nine respondents who provided answers to questions 2 and 3 described issues involving GPs. Most common were GPs being unfamiliar with the unlicensed medicine or requiring further information (five responses); GPs being unwilling to prescribe (four responses); prescribing errors and discrepancies (three responses) and products not being on the GP computer system, causing delays (two responses).

Issues relating to parents

Seven respondents described issues involving parents. These included parents not informing their GP in time to generate a prescription or their community pharmacist in time to obtain further medicine supplies before they ran out. Parents were often unaware that unlicensed medicines are not routinely stocked or available and have to be prepared specially, imported from abroad or purchased from a specials manufacturer. This sometimes resulted in interruptions to treatment. Some parents were also not aware of the short or limited shelf-lives of some products.

Other issues

Three respondents commented on the price of unlicensed medicines, one describing specials manufacturer’s costs as “excessive” and another describing the costs to primary care as “extortionate”. One respondent described issues surrounding the need for regular dispensing of a medicine which only had a 10-day shelf life. A further issue reported was difficulties in obtaining unlicensed medicines over weekends and on bank holidays from specials suppliers.

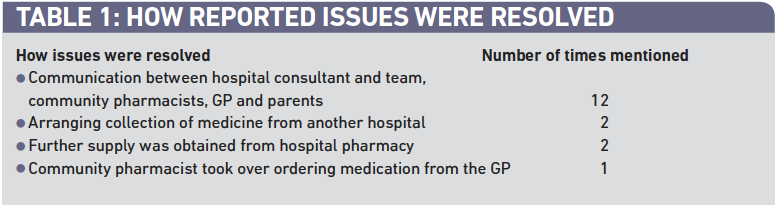

Problems were overcome in various ways and these are summarised in Table 1.

Most respondents stated that the problems described were often resolved with a simple telephone call, fax or letter between the relevant healthcare professionals to explain about the unlicensed medicines and the reasons for their use. Occasionally further supplies needed to be obtained from a hospital pharmacy or collected from another hospital. It should also be noted, however, that two respondents stated that they did not experience any problems with the supply of unlicensed specials, with one reporting that the delivery is usually with them within 24 hours of phoning the order through.

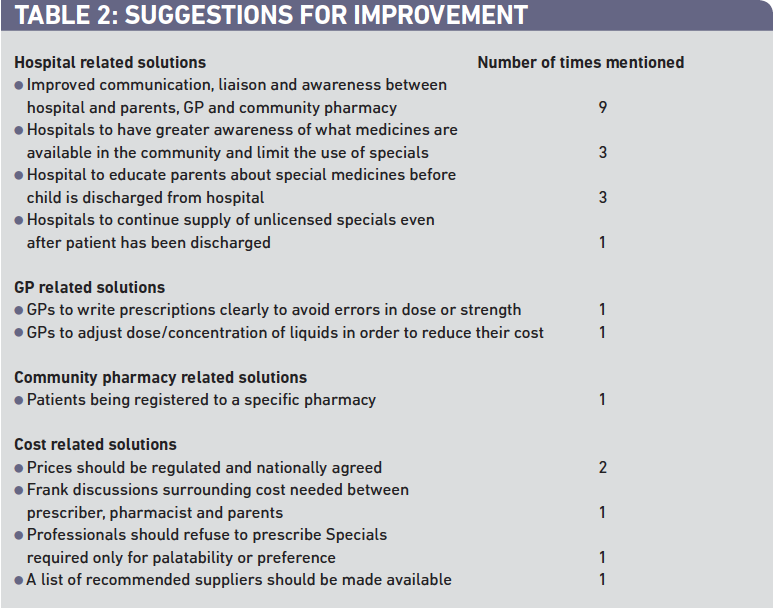

Suggestions for improvement

Twenty-four respondents provided suggestions on how things could be improved. Most of the improvements were directed towards hospital pharmacies; however improvements in other areas were also suggested (Table 2).

Problem medicines

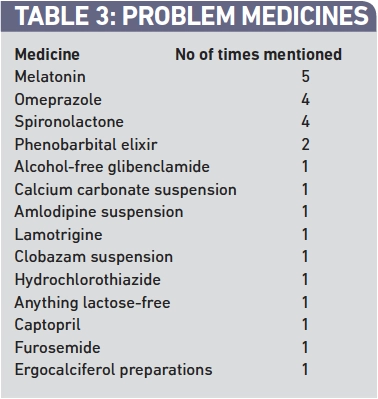

Respondents were asked to identify which unlicensed medicines they had experienced most problems with and to describe the problems. Table 3 presents the list of medicines identified. The problems associated with the three most commonly mentioned medicines are summarised below.

Melatonin

The main problems reported in relation to melatonin were that GPs are not always aware that there are different formulations of this medicine, that different strength capsules were not being stocked by wholesalers, that there were long delays in obtaining stock, and that letters were required from GPs each time the drug needed to be ordered. In the case of liquid melatonin, one respondent replied that it was an imported special that required a specialist importer. The high cost of melatonin capsules was also highlighted. In recommending improvements, one respondent suggested that the formulation of the medicine be clearly stated by the prescriber, and another reported that a local children’s unit now issues a letter with all melatonin prescriptions stating they are aware of its unlicensed status, which helps improve communication between GP, pharmacy and parents.

Omeprazole liquid

Most problems reported included the product’s short shelf-life and children being discharged from hospital without their GP being given any advice on which dose or formulation to prescribe. This had led to GPs being unwilling to prescribe the liquid or to delays in obtaining a prescription.

Spironolactone liquid

The main problem reported regarding spironolactone was that GPs were not willing to prescribe it because of its cost, but being unaware that different concentrations could reduce costs.

Discussion

Forty pharmacist members of the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire Local Pharmacy Forum responded to this brief questionnaire regarding experiences with unlicensed medicines. The number of respondents is disappointingly low and may have been a self-selected population of those who have experienced problems. The responses suggest however that pharmacists, GPs and families regularly experience problems with unlicensed medicines. Melatonin, omeprazole and spironolactone were identified as the most common problem medicines in this sample. The following key themes emerged from our respondents.

Communication

Unlicensed medicines that children are discharged from hospital with are not always familiar to GPs or community pharmacists, leading to problems for families. This may result in a GP unintentionally changing a child’s prescription, leading to reduced efficacy or to toxicity, and errors have been known to occur.7 Children may not take the medicine if it looks or tastes different and this can also lead to confusion and concern for parents. Some GPs may refuse to prescribe a medicine due to concerns or lack of information regarding product choice, doses, monitoring or cost, requiring families to return to hospital to obtain a further supply. This may involve lengthy journeys and inconvenience, and cause concern and disruption to treatment. The key issue seems to be a lack of adequate and timely communication between secondary/tertiary and primary care. Most problems described in our study were resolved by simple communication by telephone, fax or letter between the relevant healthcare professionals in order to explain the status of the medicines and the reasons for their use.

Respondents provided suggestions for how information-sharing and communication could be improved. Such suggestions included hospitals providing the family with a detailed discharge summary to give to their GP and to their community pharmacist. As has been recently highlighted11 this really needs to contain drug name, dose and frequency, duration of treatment, strength, dosage form and, for unlicensed medicines, source of supply (eg, a particular manufacturer) and specific formulation needs (eg, alcohol-free). Alternatively (and perhaps preferably) such information should be faxed from the hospital directly to the GP and community pharmacist to provide better communication between the professionals involved in the patient’s care, and a multidisciplinary understanding of which medicines have been provided and the reasons for this.

Communication between healthcare professionals and parents, and working in partnership, has been highlighted in guidance aimed at making use of unlicensed medicines in children safer.11 Parents should be made aware of why the unlicensed medicine is the best choice for their child and asked to report any problems with symptom control, adverse events or change of taste or volume of dose when their care transfers from hospital to the community.

Such improved communication channels have been recently advocated in Royal Pharmaceutical Society guidance with respect to getting all medicines right for all patients transferring across different settings.15 This guidance lists four core principles for healthcare professionals, including ensuring that all necessary information about a patient’s medicines is accurately recorded and transferred with that patient in a way that is timely and clear (preferably electronically), and that responsibility for ongoing prescribing is clear. Patients and their carers should be encouraged to be active partners in managing their medicines when they move between settings, and know what medicines they are taking, when and why. The guidance also recommends the core required content of records for medicines needed when patient care moves between settings. This includes detailed information about current medicines, any changes made and other additional recommendations around monitoring, adherence support and brand or formulation issues.15 A small study in a UK children’s hospital has already shown that greater information provided by pharmacists on discharge prescriptions was well received by GPs.16

Professional responsibilities when supplying specials

Unlicensed products should only be prescribed when there is no licensed alternative available. This may involve considering alternative drugs that will provide the desired effect if they are available in more appropriate formulations. Off label medicines, ie, using a licensed product outside the terms of the license (eg, for patients of a different age, at a different dose or by a different route of administration from that in the licence) may be safer and preferable to choosing an unlicensed product. If an unlicensed product is essential then a special or an imported licensed medicine should be considered first because these may be of higher quality than preparing an extemporaneous medicine or manipulating other formulations (eg, crushing tablets or emptying capsules and dispersing in water). Consideration of excipients in both licensed and unlicensed products is essential because these may be unsuitable for neonatal and paediatric patients, eg, phenobarbital elixir BP is 38 per cent alcohol. Patient information may not be available for unlicensed products or may not be in the appropriate language if imported from abroad. Sensible guidance and case examples have been recently published.11

The RPS also issued professional guidance in June 2010 outlining the key professional responsibilities for pharmacists providing advice on or supplying specials.8 It provides information on assessing a patient’s clinical need for these medicines, choosing suitable products and suppliers and good record keeping. It also encourages communication between pharmacists from all areas of the profession with prescribers who are not always aware that they are prescribing an unlicensed product. Pharmacists supplying unlicensed products are accountable and must be able to show that they have made patient safety a key consideration by using appropriate suppliers of unlicensed medicines, that they are assured that the product is of appropriate quality and meets the particular clinical needs of their patient.8 It is the pharmacist’s responsibility to ensure that the prescriber is aware that the product supplied is unlicensed. Prescribers are supposed to define exactly what formulation they require the medicine to be. In practice this seldom happens because most doctors are unlikely to have the expertise to do so and pharmacists are in the best position to help in this process. They should specify to the specials supplier exactly what they require in terms of the formulation, including safety of the ingredients (including excipients), bioequivalence to any previously used products or the licensed equivalent; a known stability profile for all ingredients and acceptability to the patient or their carer.10 This, in practice, sounds challenging but one relatively straightforward step could be to continue to provide the same product from the same supplier used by the hospital initiating the treatment in order to maintain bioequivalence and dose uniformity.

Manufacturers should be chosen with care and products purchased with a certificate of analysis if they are batch manufactured specials (confirming levels of active ingredients following testing the final product) or a certificate of conformity if they have been produced as an extemporaneous product under the section 10 exemption of the Medicines Act 1968 (confirming that the final product conforms to the requesting pharmacist’s specification to the best knowledge of the signatory).10

Different formulations of a drug prepared for use by children cannot be assumed to have therapeutic equivalence. One study showed that paediatric cardiac centres and their referring hospitals use a variety of unlicensed liquid captopril formulations interchangeably and it raised issues about optimal captopril dosing and potential toxicity which may influence paediatric cardiac patient outcomes.17 This research group later showed that unlicensed captopril formulations are not bioequivalent to the licensed tablet form, or to each other, and so cannot be assumed to behave similarly in therapeutic use.18 They highlighted that formulation substitution must be done with care and may require a period of increased monitoring of the patient.18 Hospital pharmacists should provide information about the products children are sent home with and community pharmacists should endeavour to continue to supply these, especially where therapeutic equivalence is likely to be particularly important.

Education of carers

Another problem often faced by the respondents was families not being made aware of the status of unlicensed medicines or of the process of obtaining them. Respondents suggested that families should be appropriately educated before discharge about how such medicines are obtained from specials manufacturers and the time that may be required to do this. Parents presenting at community pharmacies are often under the impression that the medicines will be “on the shelf” and immediately available to them. Respondents described experiences of parents presenting at community pharmacies when their child’s current supply of medicine had ran out and expecting the pharmacy to be able to source another supply the same day. due to the nature of unlicensed specials, this is often not possible to do and can result in delays and treatment interruptions. Terry and sinclair recently highlighted an example where a family who needed an urgent further supply of an essential medicine presented at a Uk specialised children’s hospital on a Friday evening, having failed to obtain their child’s essential medicines from a community pharmacy.19 These authors suggested that hospitals should be mandated to continue to provide these items and funding streams should be put in place to provide resources for them to do so. This is a controversial suggestion which would not be welcomed by all. However, it was also suggested by one of our respondents.

Cost

The high cost of specials in the community was also highlighted as an issue. Two respondents suggested that prices of unlicensed specials should be nationally agreed and regulated, and one respondent stated that specials should not be prescribed only for palatability or preference. NHS costs of supplying unlicensed medicines have been reported to have risen from £57m to £160.5m in four years with wide ranging prices being charged for apparently the same medicines.20 Different specials companies have been known to charge hugely varying prices for their products and the issue has been compounded by wholesalers adding on costs. The introduction of the new specials tariff may help to reduce this issue by creating “a more transparent system for reimbursing specials, linking the cost of reimbursement to the cost of the product, while providing value for money for the NHS’’.21 six of the medicines mentioned in our survey are included in the tariff.

Is an unlicensed product the best choice?

For many years pharmacists have been ethically required to provide licensed medicines whenever a suitable one is available. our survey raises the question as to whether we need to be more proactive in this area both in hospital and community by recommending, for example, slight dose adjustments to avoid the need for a special liquid or to suggest another drug from the same therapeutic class that is available in a more suitable formulation. omeprazole liquid was highlighted as causing problems in our study. This preparation has been reported to have cost the NHS in England almost £500,000 in one month (September 2009) alone.10 many of these liquid preparations involve dissolving the drug in sodium bicarbonate to make a solution. According to the summary of product characteristics omeprazole is a weak base and is concentrated and converted to the active form in the highly acidic environment of the intracellular canaliculi within the parietal cell, where it inhibits the enzyme H+k+-ATPase — the acid pump.22 This raises the question as to whether the drug is even active in liquid formulations where it is dissolved in an alkaline solution. Van der Pol et al, in a recent review, stated that proton pump inhibitors are not effective in reducing gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in infants and placebo controlled trials in children are lacking.23 It is unclear from this review which preparations were used — be these the licensed formulations or the unlicensed liquid products. The authors state that the drugs appear well tolerated in short-term use but evidence supporting safety is lacking.

Melatonin was also reported to have cost the NHS in England more than £334,000 in one month (September 2009) alone.10 A double-blind, placebo-controlled study undertaken in 21 centres in England and wales involving children with neuro-developmental delay provided strong evidence that melatonin does not improve total sleep time by a significant amount.24 On average the children treated with melatonin slept less than 16 minutes longer than those in the placebo group. Again this begs the question of whether the NHS should be spending such huge sums on unlicensed medicines that do not appear to be effective and more importantly where we cannot even be sure of their safety or quality.

Conclusion

The use of unlicensed medicines in children is not a new issue but is clearly continuing to cause problems for patients, families, pharmacists and doctors in hospital and community. Pharmacists in all sectors have a highly valuable role to play. In particular they should be proactive in ensuring that these medicines are used only when absolutely essential and should advise prescribers on alternative doses, drugs and formulations to avoid their use if possible. Communication between sectors is key to minimising problems and disruptions to treatment for patients transferring between different care settings. This should be done in a proactive manner and involve the family and hospital and community prescribers and pharmacists. Education of parents and carers about these medicines should be done sensitively without worrying them, but should make them aware of the need for, and their responsibilities of, timely communication with their GP and community pharmacists when needing further supplies. Purchasing responsibly is also a vital role for pharmacists with due regard to timeliness of supply, quality assurance, bioequivalence and cost.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Helen Boardman and Lianne Denton for organising the survey through the RPS and to all those who participated. This project was funded as part of a project using a grant from the Neonatal and Paediatric Pharmacists Group.

References

- Conroy S, McIntyre J, Choonara I. Unlicensed and off label drug use in neonates. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal and Neonatal Edition 1999;80:F142–5.

- Conroy S, Choonara I, Impicciatore P et al. Survey of unlicensed and off label drug use in paediatric wards in European countries. BMJ 2000;320:79–82.

- McIntyre J, Conroy S, Avery A et al. Unlicensed and off label prescribing of drugs in general practice. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2000;83:498–501.

- Gill AM, Leach HJ, Hughes J et al. Adverse drug reactions in a pediatric intensive care unit. Acta Paediatrica 1995;84:438–41.

- Turner S, Nunn AJ, Fielding K et al. Adverse drug reactions to unlicensed and off-label drugs on paediatric wards: a prospective study. Acta Paediatrica 1999;88:965–8.

- Impicciatore P, Mohn A , Chiar elli F et al . Adverse drug reactions to off-label drugs on a paediatric ward: an Italian prospective pilot study. Paediatric and Perinatal Drug Therapy 2002;(5):19–24.

- Conroy S. Association between licence status and medication errors. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2011;96:305–6.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Dealing with specials. Pharmacy Professional 2010;(June):27–32.

- Picton C. National Prescribing Centre. Prescribing specials: Five guiding principles for prescribers. Liverpool: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2011.

- NHS East of England. Information and guidance on the prescribing and use of unlicensed pharmaceutical specials. East of England NHS Collaborative Procurement Hub, 2010.

- Tomlin S, Cockerill H, Costello I et al. Making medicines safer in children — guidance for the use of unlicensed medicines in paediatric patients. Connectmedical, 2009.

- European Medicines Evaluation Agency. The European paediatric initiative: history of the paediatric regulation. London, EMEA, 2007. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu (accessed 1 June 2012).

- Wong ICK, Basra N, Yeung VW, Cope J. Supply problems of unlicensed and off-label medicines after discharge. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2006;91:686–8.

- Mukattash T, Hawwa AF, Trew K et al. Healthcare professional experiences and attitudes on unlicensed/off-label paediatric prescribing and paediatric clinical trials. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2011;67:449–61.

- Picton C. Keeping patients safe when they transfer between care providers — getting the medicines right. Good practice guidance for healthcare professions. London: Royal Pharmaceutical Society, 2011.

- Villalba-Mendez C, Missen L. Improving discharge standards for children’s medicines. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 2011;3:185–6.

- Mulla H, Tofeig M, Bu’Lock F et al. Variations in captopril formulations used to treat children with heart failure: a survey in the United Kingdom. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2007;92:409–11.

- Mulla H, Hussain N, Tanna S et al. Assessment of liquid captopril formulations used in children. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2011;96:293–6.

- Terry D, Sinclair A. Children’s “specials” need to be more easily available. Pharmaceutical Journal 2011;286:196.

- Are specials out of control? Pharmaceutical Journal 2011;285:463.

- NHS Prescription Services. Introduction of a “specials” tariff from November 2011. London: NHS Business Services Authority, 2011.

- AstraZeneca UK Ltd. Summary of Product Characteristics, Losec Capsules. London: electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC), 2011.

- van der Pol RJ, Smits MJ, van Wijk MP et al. Efficacy of proton-pump inhibitors in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2011;127:925–35.

- Appleton R, Gringras P. Mends: the use of melatonin in children with neurodevelopmental disorders and impaired sleep — a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel trial. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2011;96(Suppl): As1.

You may also be interested in

Have parents’ views on using community pharmacy services for children in the UK changed over the past ten years?

Measles vaccinations should be compulsory for pre-school children, study concludes