Abstract

Aims

To investigate the current level of patient awareness and interest in health care in black and minority ethnic communities. To reduce language and cultural barriers between patients and health care professionals.

Method

Local community groups interested in information and advice sessions were contacted using primary care trust resources. A generic presentation providing core information was developed. Each presentation was then tailored according to the needs of each community group. The session was delivered in the patients’ native language, using the linguistic skills of the prescribing team. Each session was followed by an opportunity for participants to ask questions and have an individual medication review, which included blood pressure measurement.

Subjects and setting

Community groups in the Dudley Beacon and Castle Primary Care Trust and adjoining Dudley South PCT.

Outcome measures

Evaluation forms in English, including pictograms were used and verbal and written feedback was taken after the sessions.

Results

There was a good level of attendance at all sessions and participants were interested in their conditions, medicines and healthy lifestyles. Participants wanted more information and to play a more active role in their health care. Speaking to patients in their own languages in their community setting broke down many barriers. Limited success was obtained with the evaluation forms.

Conclusions

Taking health care into the community has illustrated that patients are interested in their own health and willing to act upon information and advice that they may not have otherwise had access to. Pharmacists can contribute towards reducing health inequalities within the community.

Over a period of one year, practice-based pharmacists in a multicultural setting in the Birmingham and the Black Country Strategic Health Authority area reported a variety of concordance issues ranging from patients’ lack of understanding of their illness, their reasons for taking medicines, consequences of non-compliance and denial. In addition there were many cultural issues that influenced how medicines were taken. A recent study among British Pakistani and Indian patients concluded that cultural factors need to be understood and taken into consideration to ensure that these patients are given appropriate advice and to avoid unnecessary changes to prescriptions.1 Other studies showed that more than 13 per cent of patients in primary care practices did not know the indication of at least one of their prescription medicines. Lack of knowledge was most prevalent for cardiovascular medicines.2–5

There is limited pharmacy-related literature on the use of pharmaceutical services by ethnic minorities. Aslam and Wilson suggested that, in addition to having help from family members, the problem of communication could be addressed by employing staff from the local community.

The opportunity arose to try to improve patients’ awareness of medicines when Dudley Beacon and Castle Primary Care Trust’s prescribing team successfully gained funding through a clinical governance bid. The project focused on community groups within the PCT and the adjoining Dudley South PCT, and used a team of pharmacists who, collectively, spoke five different languages. Some of the community groups had previously been identified by the public health department within the PCT as being disadvantaged from a health equity perspective.

The aims of the project were to increase the awareness of medicines and their use within black and minority ethnic communities in Dudley borough. This group was targeted since it was well known that the uptake of and access to health care services was more difficult due to social, cultural, religious beliefs and language barriers.

It was also intended to allow patients the opportunity to ask about their medicines and get further individual information tailored to their particular needs.

We hoped to provide access to pharmacists as an additional source of information with regards to health. The pharmacists could identify patients who were suffering poor health and provide signposting to appropriate health care services and follow up.

Methods

Community groups were contacted to explore whether they would be interested in pharmacists talking to them about medicines. This was facilitated by the PCT’s community health development adviser, who identified the needs of each group and established a point of contact. For each of them, a timetable and venue was agreed and this was advertised using posters in appropriate languages.

Focus group sessions were developed to raise awareness of medicines, since group interaction has been suggested to be a valuable way of stimulating questions.

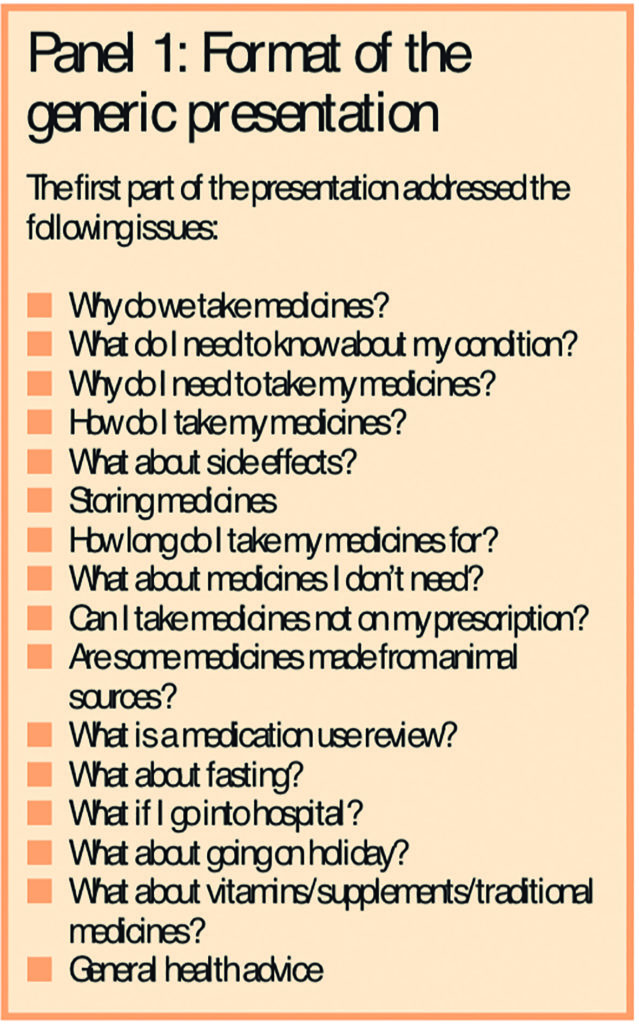

Each session included a generic presentation (Panel 1), which was adapted to the specific needs of each group and included appropriate audio visual aids. It was delivered in the appropriate language, using the linguistic skills within the pharmacy team, apart from one session where communication with the Arabic speaking Yemeni community was provided by an interpreter.

The second part of the session was tailored to meet the needs identified by the individual groups. These included information on the haj and umrah pilgrimages in the form of a travel consultation (where attendees were given pointers as to what they might need to know about their health before travelling), medicines taken during Ramadan for the Dudley Muslim Association and advice on a healthy diabetic diet for the Sikh community.

Participants were offered an opportunity to have a face-to-face medication review with a pharmacist that included blood pressure monitoring with follow up or referral where appropriate.

The pharmacy team consisted of practice-based and local community pharmacists, many of whom already had good relationships with the communities. They were provided in advance with a copy of the presentation and were offered refresher training to ensure a consistency of approach during sessions. This training included highlighting side effects, discussing contraindications and drug-monitoring requirements for sample prescriptions, and guidance on the PCT’s approved medication review process. The pharmacists were also trained to record blood pressure and use forms to record comments and feedback, on which practice-based pharmacists or surgeries could act.

An evaluation form for participants was devised, using suitable pictograms, to enable assessment of the benefit of sessions.

Results

Six sessions were held, identifying a range of medicines awareness, lifestyle and public-health issues. These are outlined in Panels 2 and 3.

It was found that participants benefited from presentations in their own language and community and that they also valued the opportunity to discuss their medicines with pharmacists. Details of the sessions held, numbers of participants and pharmacists involved, including individual interviews and intervention forms completed, are given in Table 1.

Where medication reviews were carried out, blood pressure measurements were taken. Twenty-nine per cent of the medication reviews (20 out of 70) revealed patients with poorly controlled hypertension. Significantly, within the Caribbean Association, 15 out of 26 patients (56 per cent) had blood pressure greater than 150/90mmHg. People with readings greater than 150/90mmHg (the target stated in the general medical services contract) were given advice and referred to their GP, practice-based pharmacist or practice nurse.

The use of evaluation forms by participants was not successful. The main reason for this was probably due to language difficulties, despite the use of pictograms. However verbal feedback at the end of each session was positive. Participants said the sessions were both valuable and enjoyable. They particularly appreciated having their blood pressure taken and were keen for further sessions to be arranged in the future. They also expressed an interest in cholesterol measurements.

Overall, a large number of people did not know what a medication review is or why it is important. People were generally interested in what to expect from a medication review. However the Yemeni community, while happy to engage in discussion at the end of the session, were not keen to participate in the medication review process.

Discussion

Overall, this project was considered successful. People wanted to know more about their medicines and their medical conditions, in particular diabetes and hypertension, which were poorly understood.

Almost a third of the participants and over half from the Caribbean Association had uncontrolled hypertension.

Of the medication reviews conducted, 61 per cent resulted in an intervention. Interventions included the identification of compliance and concordance issues, side effects due to medicines taken, advice and signposting for diabetes-related conditions, as well as recommendations for prophylactic medication and the identification of more serious conditions, such as atrial fibrillation, which was suspected when a participant’s pulse was taken and later confirmed by their GP.

Valuable lessons were learnt, in particular the concept of taking health care to the patient, finding out what patients want and providing them with information to empower them.

In order to make informed decisions about their medical treatment, patients must understand the risks and benefits of and alternatives to treatment and that patient education may also improve adherence to drug therapy.2–5 Health care professionals have an important role in achieving this.

The key to success requires adaptation from both a patient and health care professional perspective. Health care professionals need to be aware of the different traditional, social and cultural influences when negotiating treatment regimens and offering advice to patients. Pharmacists are well placed to do this, developing a rapport built over time through regular contact with patients, often in an informal manner. Speaking to patients in their own language and understanding personal and cultural influences on health care and medicine-taking was important in delivering the message to ensure and improve patient compliance and concordance. In turn, this should lead to better long-term health outcomes. Participants liked the flexibility of the sessions’ structure and enjoyed the interaction at the end most of all.

The only sessions not delivered by a pharmacist in the appropriate language were those to the Yemeni community. With this group, medication reviews were not done, indicating that the language barrier has a great impact on the way patients inter-relate directly with health care professionals.

Further development of the evaluation forms is required in order to improve the level of feedback. Remaining monies from the project were used to fund the translation of the PCT’s “No antibiotics” campaign leaflets into five different community languages. In addition, further monies have been awarded to extend the project by taking medicines education and awareness sessions to more patients and carers into their community settings. The sessions will continue to be tailored to individual groups needs. It is hoped that in the long term this will become a core service provided by the prescribing team and will continue to utilise and develop skills within the team such as supplementary prescribing.

This piece of work won a team-working award at the PCT’s annual “Celebrating success” event, highlighting how well the prescribing team work together and how they interact with other teams working in the PCT and the community.

Acknowledgements

We thank community health development adviser Binder Somal, and pharmacists Kiran Dhaliwall, Nazir Hussain, Jaspal Johal, Mohammed Mahroof, Nayyer Mehmood, Mohammed Nusrat, Dinesh Patel, Hitesh Patel, Suky Sandhar and Jagdeep Sangha. We also thank the elders of the Sri Krishna Temple Day Centre, the Dudley Caribbean Association and the Guru Nanak Singh Sabha Community Centre in Dudley Borough, the Dudley Muslim Association and the Halesowen Yemeni Community Association.

This paper was accepted for publication on 26 May 2006.

About the authors

Clair Huckerby, BPharm, MRPharmS, is pharmaceutical adviser at Dudley Beacon and Castle Primary Care Trust, Judith Hesslewood, BPharm, MRPharmS, is prescribing adviser at Dudley South PCT, and Parbir Jagpal, MSc, MRPharmS, is a practice-based pharmacist at Dudley Beacon and Castle PCT.

Correspondence to: Clair Huckerby, Dudley Beacon and Castle PCT, St John’s House, 2 Union Street, Dudley DY1 2PP

References

- Lawton J, Ahmad N, Hallowell N, Hanna L, Douglas M. Perceptions and experiences of taking oral hypoglycaemic agents among people of Pakistani and Indian origin. Qualitative study. BMJ 2005;330:1247.

- De Young M. Research on the effects of pharmacist-patient communication in institutions and ambulatory care sites, 1969–1994. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacists 1996;53:1277–91.

- Lipton HL, Bird JA. The impact of clinical pharmacists’ consultations on geriatric patients’ compliance and medical care use; a randomised controlled trial. Gerontologist 1994;34:307–15.

- Lowe CJ, Raynor DK, Courtney EA. Effects of self-medication programme on knowledge of drugs and compliance with treatment in the elderly patients. BMJ 1995;310:1229–31.

- Mc Donald HP, Garg AX, Haynes RB. Interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication prescriptions: scientific review. JAMA 2002;288:2868–79. (Erratum, JAMA 2003;289:3242.)

- Aslam M, Wilson JV. Ethnic minorities. In: Taylor KHG, Harding G (editors). Pharmacy Practice. London: Taylor and Francis; 2001. pp274–87.