Introduction

Many people in the community have anxiety, depression and sleep disturbances[1],[2]

but relatively few seek medical advice, and those who do are often reluctant to take prescribed medicines.[3]

Insomnia features prominently in both anxiety and depression,[2]

so it is not surprising that over-the-counter sales of sleep aids are substantial.[4],[5] However, self-treatment of insomnia may be inappropriate in cases of anxiety or depression warranting medical therapy. We studied purchasers of OTC sleep aids to examine to what extent they might have mental disorders requiring referral.

Methods

We invited the participation of all 16 Rowlands community pharmacies within the Wrexham Local Health Board area (mixed urban/rural, population 129,300) in North East Wales in May 2002. Thirteen of these pharmacies had a permanent manager in post; all agreed to participate. Procedures were reviewed and approved by the North East Wales Local Research Ethics Committee.

During normal business hours in July 2002, participating pharmacists (n=20) invited purchasers of any of nine OTC formulations advertised as sleep aids to complete anonymously a written questionnaire of demographic details, pharmacy use patterns, attitudes toward referral, and history of antidepressant prescription.

The nine OTC formulations were:

- Nytol

- Nytol One A Day

- Nytol Herbal

- Kalms

- Quiet Life

- Natrasleep

- St John’s Wort (Numark brand hypericum extract)

- Phenergan Nightime

- Sominex

Control respondents were drawn from a sub-sample (every 10th customer) purchasing other products. All participants but one completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), an established, brief, valid measure of common psychological symptoms.[6]

Scores greater than 10/21 on either anxiety or depression indicate likely clinical disorder.[6]

Customers were excluded if they were under 18 years of age, had already participated or were purchasing on behalf of someone else.

The data, collected on a paper pro forma, were collated, entered into a Microsoft Access database and analysed using statistical software (SPSS version 11.5.0). The null hypothesis was that control and target purchasers would not vary in their self-reported symptoms, attitude to possible referral, or history of anti-depressant prescription.

Results

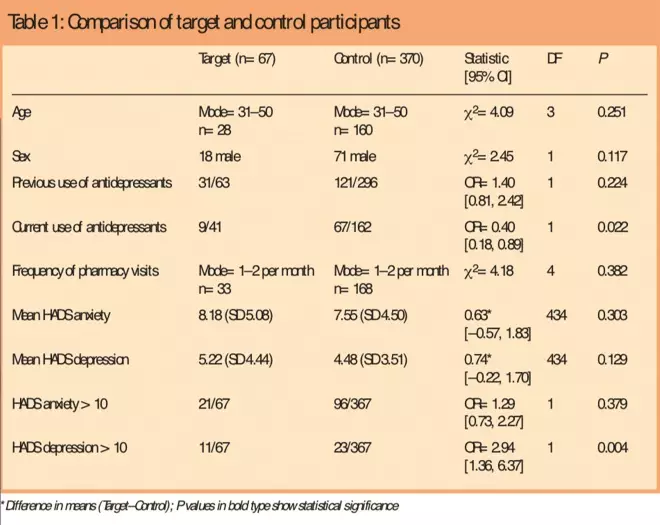

A total of 961 customers were invited to participate. Of the 773 meeting eligibility criteria, 456 (59 per cent) agreed. Those purchasing target sleep aids constituted 2.3 per cent of total customers. Target and control customers did not differ significantly in the proportion agreeing, refusing, or who were ineligible to participate (χ2=5.01, df=2, n=961, P=0.08). However, reasons for ineligibility differed; target customers were more likely than controls to report purchasing for someone else and less likely to be underage (χ2=38.7, df=2, n=188, P<0.001) but comparably likely to have previously participated. There was no evidence of response bias. Participating groups did not differ by age, sex distribution or previous antidepressant use, but target customers were less likely to report current antidepressant use (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of target and control participants

Mean anxiety and depression scores did not differ significantly between target and control customers, but a higher proportion of targets had elevated depression scores (Table 1), suggesting a higher rate of “caseness”, ie, a higher number of target customers were categorised as being “depressed”, although there was no significant difference between the means of the target and control customers.[6]

Multiple regression analysis indicated that previous but not current antidepressant prescription predicted elevated anxiety (t=5.30, P<0.001) and depression scores (t=4.90, P<0.001). In addition, age predicted anxiety score, with older customers reporting less anxiety (t=2.11, P=0.036).

Participants were asked if they would seek medical help for depression or anxiety if advised to do so by a pharmacist; 59 per cent of respondents indicated they would, 31 per cent “probably” would, and 10 per cent would not. The proportions did not vary between targets and controls (χ2=4.14, df=2, n=235, P=0.126) and did not depend on symptom scores (anxiety P=0.83; depression P=0.73).

Discussion

This study suggests that most customers of UK community pharmacies are willing to be surveyed anonymously regarding psychological symptoms, and would accept referral for medical help if necessary. The results are consistent with those of previous studies that have shown a high community prevalence of anxiety and depression[1] and suggest that community pharmacies could provide a useful setting to screen for common, treatable mental disorders. Our questionnaire completion rate (59 per cent) is comparable to that found with more expensive GP-based postal surveys[7]

and higher than reported in a previous study of OTC sleep aid purchasers.[4]

The results fail to support the hypothesis that purchasers of OTC sleep aids experience more anxiety or depression overall, although those with elevated depression scores were over-represented in the target group. It is notable that participants currently taking antidepressants were under-represented in the target group, suggesting that symptomatic individuals either take antidepressants or alternatively self-treat with OTC products. It is also of interest that symptoms of both depression and anxiety are associated with previous but not current antidepressant use, consistent with the effectiveness of these agents. Since the questionnaires were anonymous, it was not possible to validate reported use of antidepressants.

Given their relatively small numbers and only modest symptomatic difference from controls, it appears inappropriate specifically to target OTC sleep aid purchasers for mental health screening. On the other hand, further study of OTC purchasers appears warranted, particularly with regard to symptom history, product choice and outcome. For example, one of the available products, hypericum, appears effective in moderate-to-severe depression if taken in sufficient doses.[8],[9] It would, therefore, be of interest to determine if hypericum purchasers differ from purchasers of other sleep aids in outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank participating customers and pharmacists in North East Wales, and Emma Bedson for assistance with data management.

Funding

The work was supported by a Pharmacy Practice Development Grant, Welsh Assembly Government.

David B. Menkes, MD, PhD, is professor and Gary P. Slegg, MSc, is research fellow in the section of psychological medicine at Wrexham Medical Institute Academic Unit, Technology Park, Wrexham LL13 7YP. Nicola F. Roe, BSc, MRPharmS, is pharmacy service development manager at Rowlands Chemists

Correspondence to Professor Menkes (e-mail: menkes@doctors.org.uk)

References

[1] Bebbington PE, Marsden L, Brewin CR.The need for psychiatric treatment in the general population: The Camberwell Needs for Care Survey. Psychological Medicine 1997;27:821–34.

[2] Singleton N, Bumpstead R, O’Brien M, Lee A, Meltzer H. Psychiatric morbidity among adults living in private households. 2000. International Review of Psychiatry 2003;15:65–73.

[3] Manning C, Marr J. “Real-life burden of depression” surveys — GP and patient perspectives on treatment and management of recurrent depression. Current Medical Research Opinion 2003;19:526–31.

[4] Phelan M, Akram G, Lewis, M, Blenkinsopp A, Millson D, Croft P. A community pharmacy-based survey of users of over-the-counter sleep aids. Pharmaceutical Journal 2002;269:287–90.

[5] Pillitteri JL, Kozlowski LT, Person DC, Spear ME. Over-the-counter sleep aids: widely used but rarely studied. Journal of Substance Abuse 1994;6:315–23.

[6] Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatria Scandica 1983;67:361–70.

[7] Michalak EE, Wilkinson C, Dowrick C, Wilkinson G. Seasonal affective disorder: prevalence, detection and current treatment in North Wales. British Journal of Psychiatry 2001;179:31–4.

[8] Linde K, Berner M, Egger M, Mulrow C. St John’s wort for depression: Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. British Journal of Psychiatry 2005;186:99–107.

[9] Szegedi A, Kohnen R, Dienel A, Kieser M. Acute treatment of moderate to severe depression with hypericum extract WS 5570 (St John’s wort): randomised controlled double blind non-inferiority trial versus paroxetine. BMJ 2005;330:503–6.