Abstract

Aim

To explore the impact of a medicines management service on patient quality of life and stakeholder and patient satisfaction.

Design

Before and after study.

Subjects and settings

51 adult patients were recruited during a routine outpatient appointment at the centre for adults with cystic fibrosis, at Birmingham Heartlands Hospital in the West Midlands.

Results

There was no significant change to the quality of life of the patients. Subgroup analysis on the patient satisfaction results by disease severity did, however, suggest that patients with less severe forms of the disease were more satisfied with the medicines management service. There were concerns about communication between the stakeholders of the service, with GPs expressing concern that there was a lack of information/GP awareness.

Conclusion

Although the medicines management service had no impact on overall quality of life, it did seem to have an impact on patient satisfaction. Further research is needed to assess the true effectiveness of a medicines management service.

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited disease that mainly affects the respiratory and digestive systems. It varies in severity. Some patients present symptomatically at birth; others do not present until later.

Treatment has advanced with improvements in antibiotics, nutrition, physiotherapy and psychological support. Due to the complex multisystem nature of the disease, a multidisciplinary approach is recommended.1 This is normally provided at a specialist cystic fibrosis centre.

Patients with cystic fibrosis typically take large numbers of medicines. Most of the regular medication is prescribed by GPs. However, the newer, more complex treatments are initiated and provided by hospital pharmacies.

This process can impose a considerable burden on the patient, with long waiting times at the pharmacy and a considerable volume of material to transport home (in particular when prescribed intravenous antibiotics). There may also be problems with adherence to different drug regimens.

The NHS Plan and the Pharmacy in the Future policy documents set out the importance of having an effective system of medicines management to ensure that medicines are used in a cost-effective and safe manner and to maximise the benefit patients derive from their medicines while minimising potential harm.2

Medicines management provides an opportunity for communication between the specialist consultant, pharmacist and GP, facilitating a smooth transition of pharmaceutical care between primary and secondary care.3

Although the national Medicines Management Services Collaborative (MMSC) has examples of how medication review has improved services for some patients, no supporting evidence exists for the value of a medicines management service for patients with cystic fibrosis.

The collaboration between the West Midlands Adults with Cystic Fibrosis Centre (WMACFC) at Birmingham Heartlands Hospital, the University of Birmingham and Lloydspharmacy provided a unique opportunity to evaluate the effectiveness of a medicines management service in this context. The study addressed the following questions:

- Does a medicines management service improve the quality of life of patients with cystic fibrosis?

- Does such a service improve communications between health professionals across primary and secondary care and help them work in partnership?

Methods

Study design and patient recruitment

A before-and-after study was undertaken where the before phase comprised 10 weeks of usual care and the after phase extended over four months. During the before phase, there was no change to the service and information on the type and level of services used by patients was recorded. After 10 weeks of observation, the patient entered the after phase and received the medicines management service for four months. Data were collected at specific intervals. The after phase was longer since it was thought that patients needed time to experience, adapt to and form a judgement about the medicines management service. A research nurse recruited adult patients attending the outpatient clinic if they were under the clinical responsibility of Heartlands Hospital, lived at a permanent address in the community, and were willing to consent to Lloydspharmacy providing the medicines management service. Inpatients and patients with no permanent address were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Birmingham East District Research and Ethics Committee approved the study design.

The medicines management service

Throughout the after phase, the medicines management service provided a comprehensive home delivery service of all prescription medication within 24 hours and home visits by the community pharmacist to review medication. Before the first home visit, the community pharmacists were given a summary of the patient’s hospital notes, including medical, social and prescription details.

The initial visit lasted about one hour and 15 minutes. The pharmacist asked the patients to make available for review all their medicines, whether hospital, community or over the counter. The pharmacist then discussed each medicine with the patient to assess compliance and concordance and to ensure that the medicines were being taken in accordance with hospital prescription records. The pharmacist ensured that patients understood how and why they were taking each medicine and, if necessary, counselled the patient. Any interaction between over-the-counter and prescribed medicines was assessed. Finally, the pharmacist removed out-of-date or unwanted drugs.

After the review with the patient the pharmacist discussed any discrepancies or problems with the hospital or GP. The GP was advised of recommended changes to repeat prescriptions. The general objective of the home visits was to improve the management of existing medication. Alterations to prescription medicines were only suggested if it was believed this would make things easier for the patient.

A follow-up visit was made at the end of the after phase to reinforce advice, assess compliance and provide an opportunity for patients to ask questions. Throughout the after phase all outpatient and primary care prescriptions were delivered to the patient. During this phase Lloydspharmacy acted as a home care provider by supplying all outpatient medicines against hospital prescriptions and invoicing the hospital monthly. This allowed patients to return home after their appointment without having to wait at the hospital pharmacy.

Control group

Because of the nature of the intervention, no placebo could be provided. To allow patients the opportunity to reflect on and form a judgement about the new medicines management service a before-and-after design was deemed appropriate. The control element was the usual care provided in the before phase, where patients presented prescriptions at the hospital pharmacy.

Outcome data and analysis

For the outcome measurement we used three data-collection instruments: a patient satisfaction questionnaire, the cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument and a critical incident form. Patient self-assessed quality of life was measured using the validated cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument.4 Patient satisfaction was assessed using two instruments: a purpose developed satisfaction questionnaire and a critical incident form. The patient satisfaction questionnaire contained items derived through discussion with clinical staff at Heartlands Hospital directly involved with the delivery of patient care.

Patients were asked to rate a series of statements about aspects of the service on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree). The aim was to measure patient satisfaction with each service design, this being the service during the before phase or the medicines management service in the after phase.

The questions for each phase were different. This reduced the direct comparability of the two phases since some elements of provision only applied to one phase or the other.

The purpose of the questionnaire was to provide information on the feelings of patients in terms of thoughts and understanding, and general satisfaction. The data were therefore treated separately, the first representing a level of satisfaction with current, usual service and the other relating to the medicines management intervention.

The cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument is a validated disease-specific instrument that was used to elicit quality of life information for both phases of the study so direct comparisons can be made. Both the quality of life instrument and the patient satisfaction questionnaire were administered at the end of the before and after phases. In addition patients recorded any issues, good or bad, about the service by completing a critical incident form issued at the end of each phase of the study and half way through the after phase.

Staff perceptions were recorded using telephone interviews or a questionnaire. Three relevant staff groups were identified: staff providers at Heartlands Hospital who had direct contact with the patient group; primary care trust (PCT) representatives who would ultimately be responsible for commissioning a service; and GPs with patients in the study. The providers and PCT representatives were interviewed by telephone and the GPs were asked to complete a one-page questionnaire about the project. Any GP who expressed concern about the service was interviewed in a follow-up telephone call.

Alongside patient demographic information, disease severity was recorded, with the number of intravenous antibiotic days in a year (2003) used as a measure of severity (treatment burden score). If the number of days fell within the range of 0–60 the patient was recorded as “mild” (code 1); if greater than 61 days then the patient was recorded as “severe” (code 2).

It was thought that the traditional severity grouping using the cystic fibrosis clinical bands 1–5 was not appropriate because the allocation to a particular band partially depends on whether antibiotics are given to the patient as an inpatient or outpatient. In reality, some patients with more advanced disease elect to have antibiotic treatment at home rather than in hospital and some patients with milder disease prefer antibiotic treatment as inpatients. Therefore the use of the number of intravenous antibiotic days was thought to be a more appropriate measure of severity. We will call this severity grouping the treatment burden score.

Results

Patient details

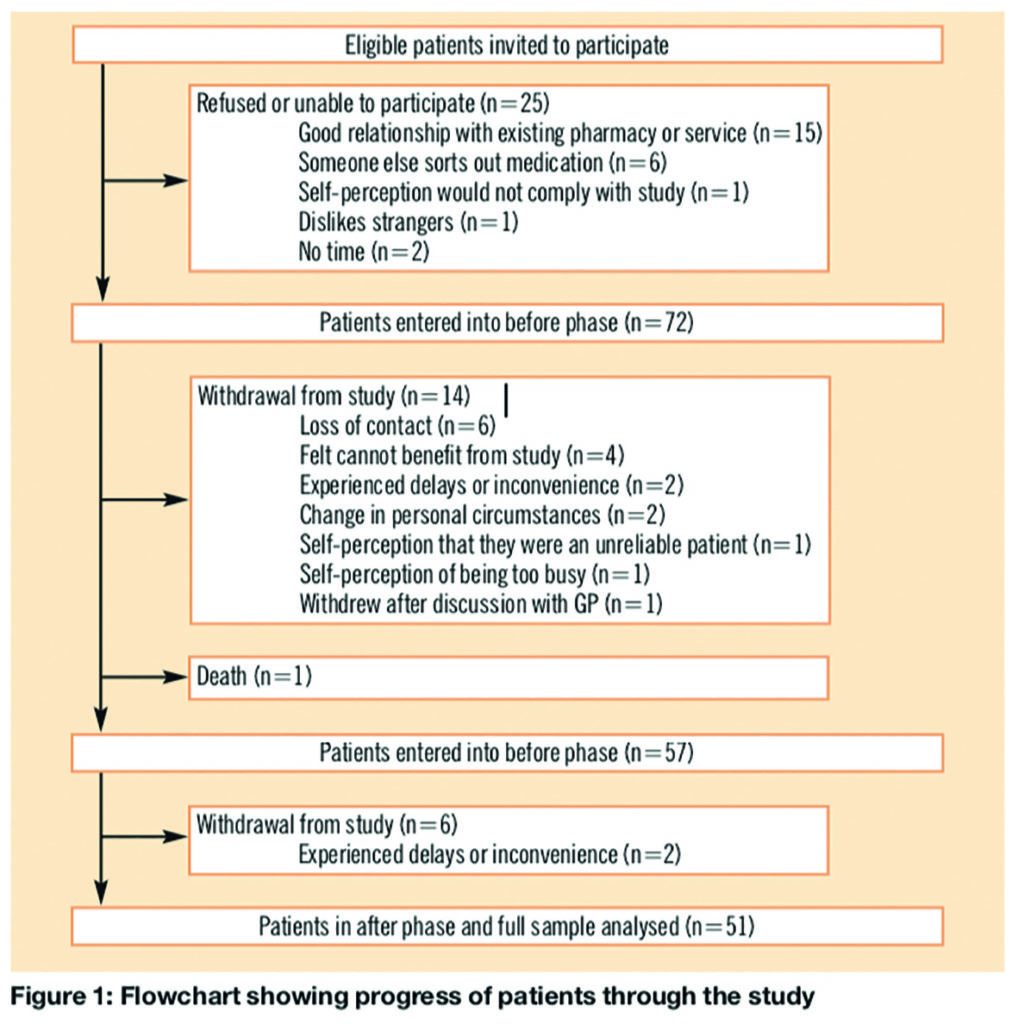

Between July 2003 and January 2004, 97 patients were invited to participate; 72 (74 per cent) patients agreed. During the study 20 patients withdrew, 14 in the before phase and six in the after phase. Patient progress and reasons for withdrawal are outlined in Figure 1. Not all patients provided a reason and some offered more than one reason. Full analysis was conducted on patients who completed both phases of the study, hence the 51 patients who completed the after phase.

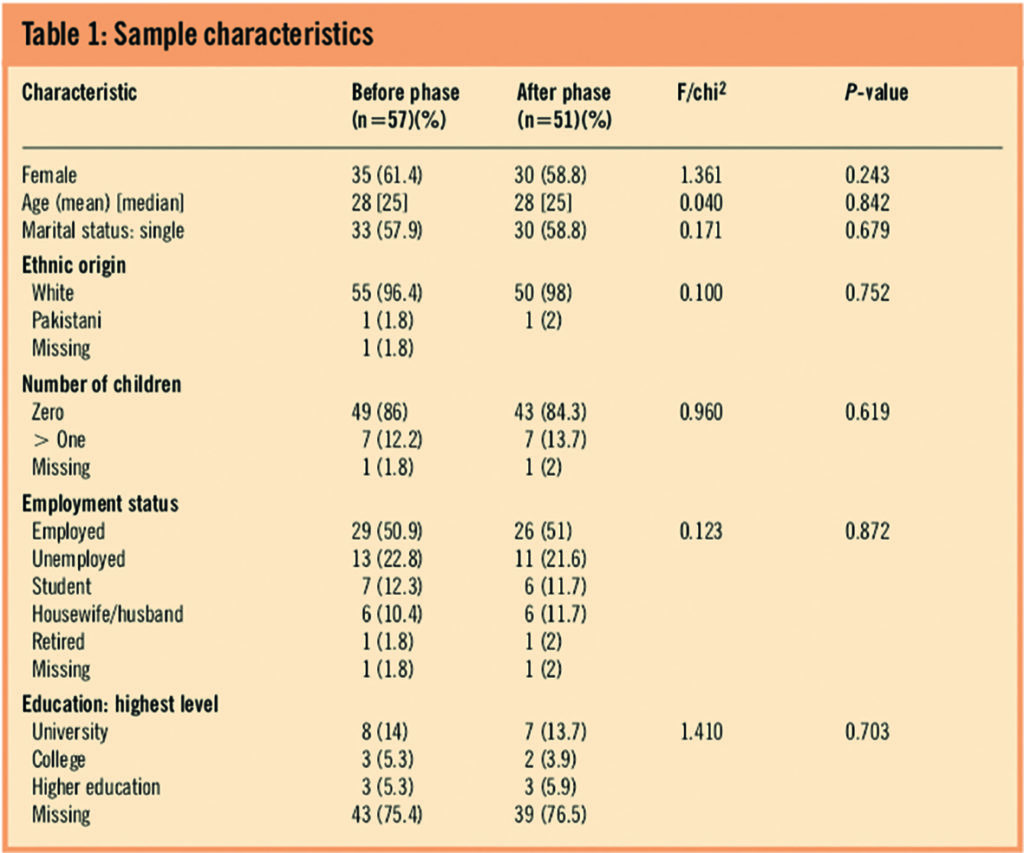

Demographic details of the study sample for both phases are displayed in Table 1 with the appropriate statistical test results for any differences. There are no statistical differences in the demographics between the before and after phase.

Medicines management visits

During the after phase all patients received the medicines management service and the pharmacists recorded 136 interventions during the medicines management visits. Of these, 90 (66 per cent) involved only the pharmacist and did not require referral to other healthcare staff. These interventions were classified as suggested by Krska et al.5

- Need for education: 77 (86 per cent)

- Compliance issue: nine (10 per cent)

- Out of date medicines: three (3 per cent)

- Repeat prescribing: one (1 per cent)

The remaining interventions included the GP (25 per cent), hospital (5 per cent), hospital and GP (2 per cent) and the community pharmacy (2 per cent). Of 37 interventions recommended to the GP 35 were followed up successfully. Of these, 33 (94 per cent) accepted the recommended advice and agreed to act on it. Two (6 per cent) did not accept the advice, and two (6 per cent) had no response recorded. Two recommended interventions were not accepted by the GP because they related to the pharmacist suggesting new medication that was not in the formulary.

After follow-up by the pharmacist, 20 prescription changes were recorded. These can be classified into the following groups (as suggested by Zermansky et al6):

- Formulation change: 15 (75 per cent)

- New drug started: two (10 per cent)

- Drug stopped: one (5 per cent)

- Dose changed: one (5 per cent)

- Other (label change): one (5 per cent)

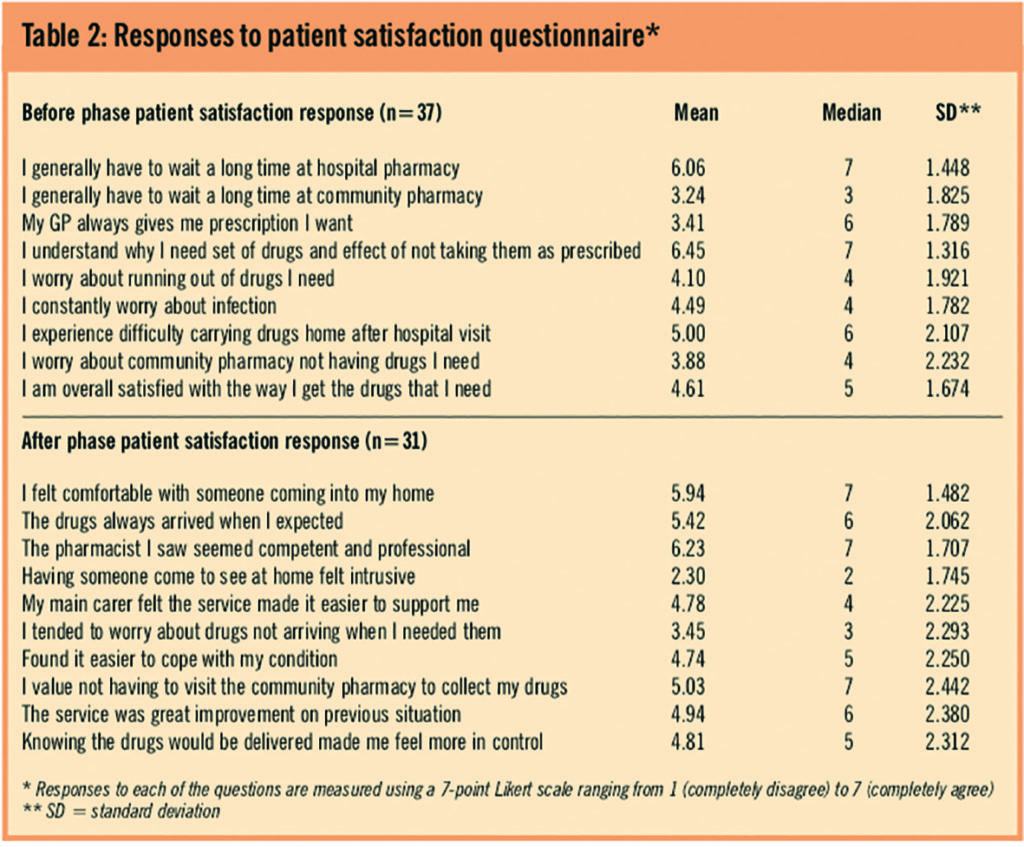

Patient satisfaction with intervention

Thirty-seven (73 per cent) patients completed the satisfaction questionnaire in the before phase. Patients were unhappy with the time they have to wait at the hospital pharmacy. A mean score of 6.06 suggested a considerable degree of agreement with the statement that they have to wait a long time. This contrasts with the response to a similar statement about community pharmacy, where a mean of 3.24 suggests far less concern about waiting in this setting. Many patients indicated that they experienced difficulty in carrying drugs home after a hospital visit (mean=5). Patients believed they had a good understanding of why they have a particular set of drugs and the impact of not taking them (mean=6.45).

The after phase satisfaction questionnaire (response rate: n=31 [61 per cent]) provided useful and largely positive data on the medicines management service. It seemed that patients were comfortable with a pharmacist entering their home (mean=5.94) and this was not thought to be intrusive (mean=2.3 — a reverse scale). The pharmacists were well regarded and were viewed as competent and professional (mean=6.23).

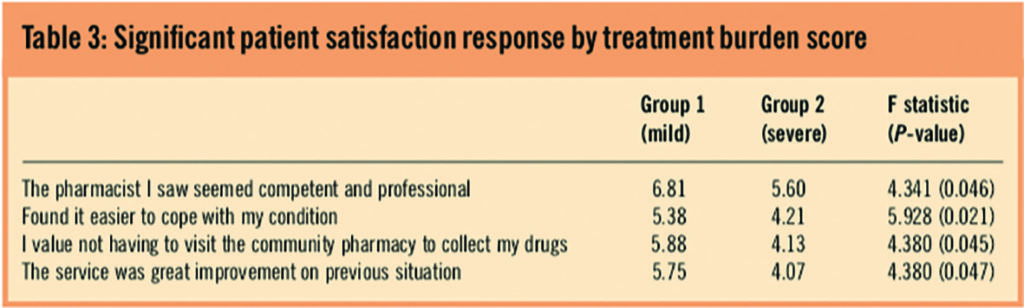

The broad sense from this group of patients was that the medicines management service was an improvement and helped them to cope with their condition. The results from the patient satisfaction questionnaire for both the before and after phase are detailed in Table 2. The patient satisfaction items were also compared in terms of condition severity, using the treatment burden score. An analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was applied to compare means between the two severity conditions.

The statistically significant items are reported in Table 3. This suggests that patients in the less severe group were more positive about these aspects of the service.

A final question in the patient satisfaction questionnaire asked how important the patients believed it was that the new service was continued, with the responses measured on a seven-point Likert scale (1=very important and 7=very unimportant). The distribution of responses to this question suggests that members of the less severe disease group (median=1.5) are more in favour of the service continuing than patients in the severe disease group (median=3) when categorised using the treatment burden score.

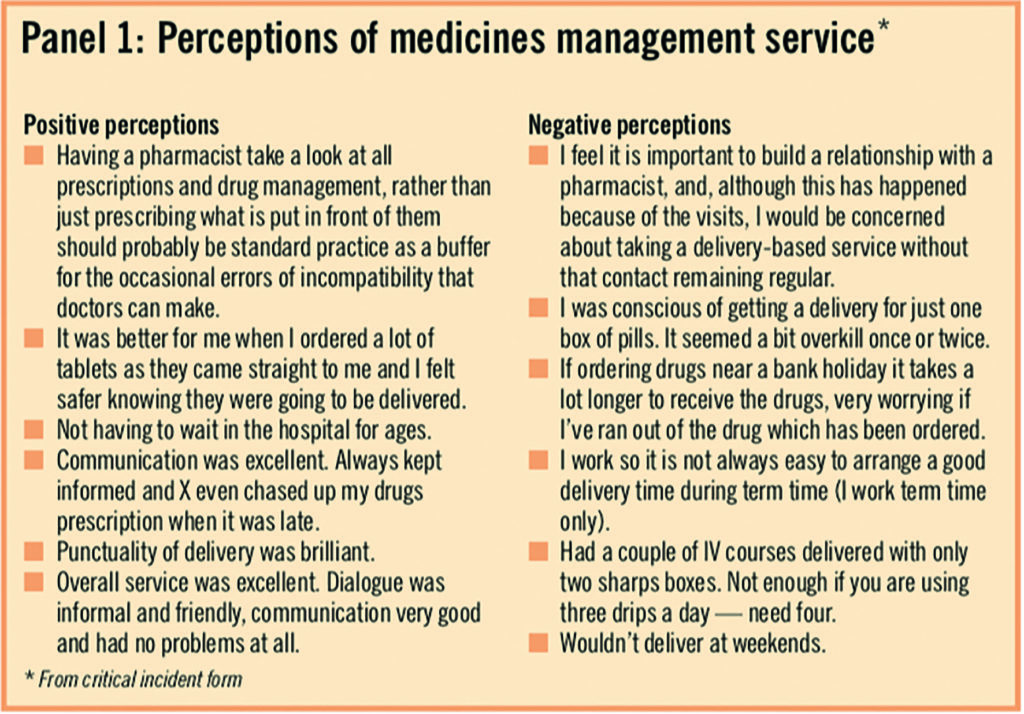

Patients were also asked to identify any issues, good or bad, about the service, using a critical incident form. A number of comments were neutral and simply descriptive of the study process. Since this was an open format measure and completed at the discretion of the patients, the results are subjective and not representative, but a selection of comments reported in Panel 1 are indicative of the type of points raised.

Staff perception of intervention

Because the service was new it was considered important to assess the views of key stakeholder groups that might be affected by the existence of a medicines management service. A small sample of staff or PCT representatives (n=2) and hospital staff (provider perspective) (n=2) were interviewed by telephone. The information collected from the telephone interviews was largely derived from an open-ended conversation from a small sample of individuals from each perspective. The results therefore are sentiments and phrases from these few people and cannot be regarded as representative but are interesting nonetheless.

PCT perspective

No specific problems were raised by the PCT representatives in the telephone interviews. However the staff did not feel particularly involved with the study and felt this was a missed opportunity because they are responsible for patients through their PCT function and relationships with GPs.

Provider perspective

Staff at Heartlands hospital generally believed that patients were positive about the service and relieved not to have to transport bulky items. One issue raised was the lack of weekend provision. It was thought that if patients needed drugs urgently this might pose a problem. Also on rare occasions there was difficulty in scheduling the visit by the pharmacist and this could result in delayed access to the medicines.

GP perspective

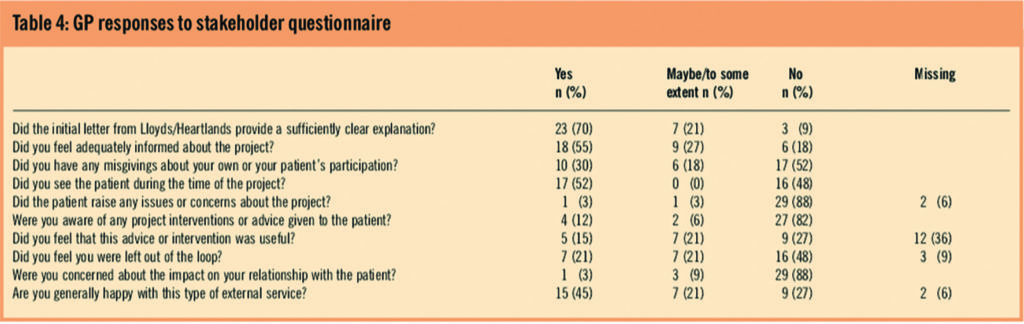

Thirty-three (65 per cent) GPs completed the questionnaire. The results are presented in Table 4.

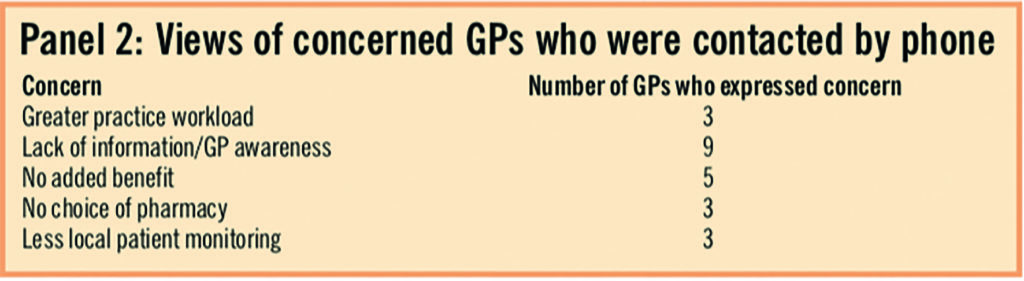

Most of the responses were positive, with 70 per cent believing that the initial letter provided a clear account of the study. However, 82 per cent said they were unaware of any intervention or advice offered to patients during the study and a similar number (88 per cent) were concerned about a possible impact on their relationship with the patient. In the context of potential roll-out the concerns of some GPs were investigated via a telephone call (33 per cent). The results of these calls are summarised in Panel 2. There was some concern about greater practice workload relating to the primary care prescriptions, however this element would only be present in the current study design and would not be an issue in a full roll-out. The main problem was lack of information and GP awareness. This could be addressed by improved communication between the pharmacist and the GP.

Quality of life

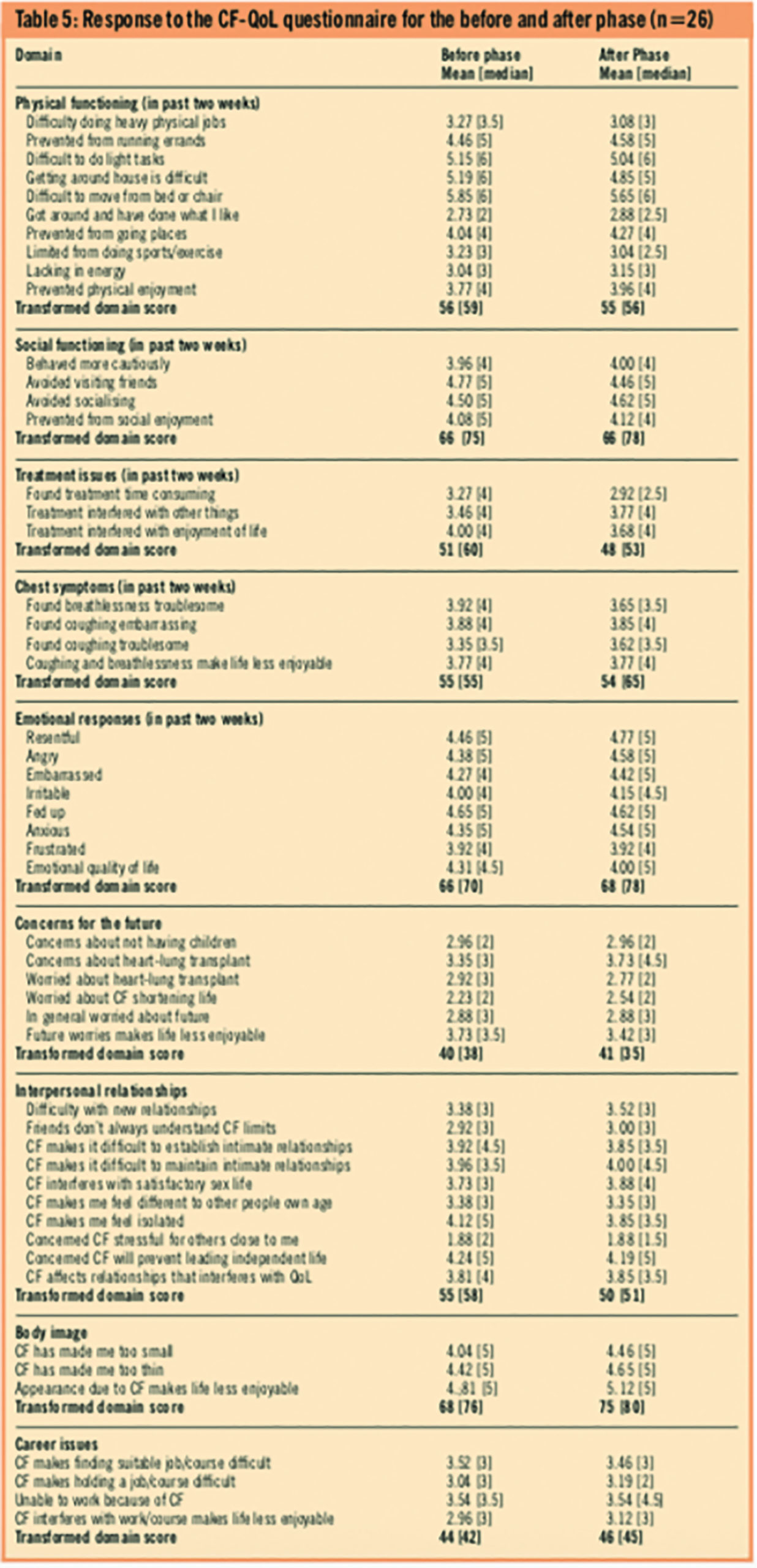

Out of 51 patients, 37 (73 per cent) completed the cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument for the before phase and 31 (61 per cent) for the after phase. Analysis of the impact of the medicines management programme upon the quality of life of patients is restricted to the patients who completed the cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument in both phases of the study (n=26; 51 per cent). The demographic characteristics of these individuals are not statistically different to the rest of the sample.

The cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument questionnaire contains 52 items in nine domains: physical functioning; social functioning; treatment issues; chest symptoms; emotional responses; concerns for the future; interpersonal relationships; body image and career issues. Responses to the questionnaire are measured by a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly agree) to 6 (very strongly disagree). Raw scores of 3 or under indicate a negative response. Each domain is scored using a weighted algorithm and presented on a 0–100 scale with zero representing worst quality of life and 100 representing best quality of life. Thus, a transformed domain score of 50 or less indicates a negative response and suggests that the individuals are experiencing difficulties with that domain. Table 5 presents the mean scores for each domain for both the before and after phase for the 26 patients who completed the questionnaire in both phases.

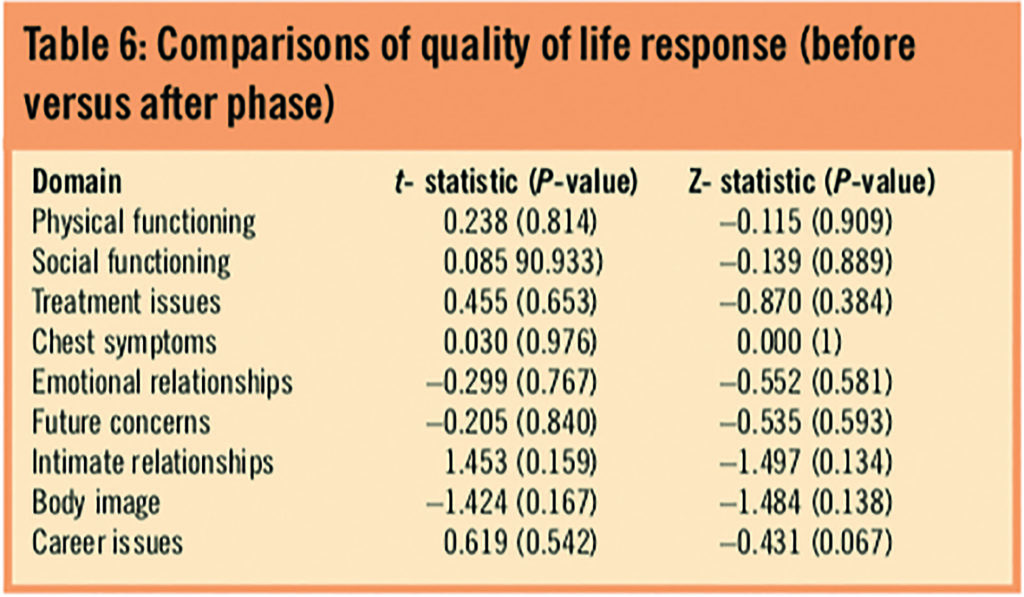

The research team used a paired sample t-test to assess the impact of the medicines management programme on the quality of life of patients. The response to each domain in the before phase is directly compared with the corresponding after-phase response. Table 6 presents the results, which indicate that there is no significant difference in quality of life across all the domains of the cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument between the before and after phase for the full sample. The same test is repeated when the sample is split by disease severity and suggests that there are no statistical differences apart from within the treatment domain score with the less severe disease group (t=2.907, P=0.013). Put differently, only the less severe patients recorded a statistically different score between the before and after phase in the treatment issues domain.

Discussion

Current policy documents have stressed the importance of regular reviews of medicines management services in the community. Lord Darzi in his recent review of the NHS recommends delivering care closer to home and ensuring that all chronically ill patients have a personalised care plan.7 There are many examples of how medicines review improves services for patients but to date no evidence exists that justifies this system of care within cystic fibrosis.

A common pattern of treatment in the UK is for patients to obtain repeat prescriptions from their GP and to visit a community pharmacy to collect the medicines. Most patients visit a specialised cystic fibrosis unit where intravenous antibiotics are prescribed and then obtained at the hospital pharmacy. This can impose a considerable burden on patients due to long waiting times, alongside the inconvenience of transporting the large volume of drugs and other items home.

In response to patients reporting considerable inconvenience, Lloydspharmacy in collaboration with Heartlands hospital developed a medicines management service designed to overcome some of the problems encountered by patients. Specifically, the service was developed with the objective of improving patient education with the help of a community pharmacist visiting the patient at home, and to decrease the burden to patients through home delivery, within 24 hours, of all dispensed medicines. This study was designed to measure quality of life and stakeholder and patient satisfaction.

Our findings suggest no significant impact on quality of life as a result of the medicines management service. The medicines review was intended to help patients understand their drugs better, increase adherence to drug regimens, remove any out-of-date medicines, report possible drug interactions or reactions to the GP and to suggest alternative medicines. We expected a change in quality of life a priori but accept, with hindsight, that our choice of quality of life instrument may not have been sensitive enough for this purpose.

The cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument is a general cystic fibrosis questionnaire that seeks to address a wide range of issues associated with having the disease. One explanation is that the intervention did not impact upon these general issues but did affect patient quality of life in other areas that were not incorporated within the cystic fibrosis quality of life instrument questionnaire.

The future issues domain, for example, asks questions relating to future fertility problems, life expectancy, the possibility of a future heart-lung transplant etc. These issues are not likely to be affected by the medicines management service. Overall, the quality of life of patients did not improve significantly, but when analysed by disease severity, the treatment issues domain improved significantly in the less severe group.

Our patient satisfaction questionnaire was designed to ask questions pertaining to the actual service received to gauge the feeling of the patients in terms of thoughts and understanding and general satisfaction with the before phase (usual care) and the medicines management service. For this reason, and since this is an unvalidated instrument, the responses from the before and the after phases are not directly compared. The results of patient satisfaction in the before and then in the after phase are presented separately.

The manner in which some of the questions were phrased could have led the respondents to a positive response towards the medicines management service. However, the patients were given the opportunity to disagree as well as agree with each statement so if the patients felt strongly enough they could have expressed that disagreement.

Although we could not directly draw comparisons between the before and after phase, the patient satisfaction results between the two disease severity groups within each phase of the study can be compared. These results suggest that the intervention was favoured more by patients with less severe forms of the condition. The nature of the disease in its mild form means that patients have little contact with the medical profession, many lead close to normal lives with most in full-time occupations.

The medicines management service provides these patients with an opportunity to liaise with community pharmacists to enhance their understanding of their condition and removes the burden of collecting and transporting medicines thus helping patients to lead a normal lifestyle.

One important finding from this study is that for medicines management to improve the pharmaceutical care between primary and secondary care, GPs need to be adequately informed. A number said that they were unaware of any intervention or advice offered to their patient and were worried about a possible impact on the doctor-patient relationship. This was surprising given that all GPs received a summary letter detailing interventions at the end of the study. It is envisaged that this issue could be adequately addressed should the medicines management service become established, but an important part of this process would be to involve GPs at an early stage.

The Department of Health encourages the practice of medicines management for all patients with chronic conditions.8 Positive results have come from medicines management focused on other diseases such as heart failure.9 The HOMER trial, however, reported counterintuitive results since it was found that medicines review led to a higher rate of hospital admissions among older people.10 This finding led to the conclusion that more research is needed to explore the most effective model of delivering a medicines management service.

Overall, we have shown from this study that a medicines management service for patients with cystic fibrosis has the potential to reduce the burden of the disease. Outsourcing outpatient dispensing can release hospital pharmacists’ time to focus on inpatient activity. Through the use of the patient satisfaction questionnaire, the research showed that patients had a favourable attitude towards the intervention. However, this instrument was purpose-built for the study and therefore offers more of a suggestion of the expected outcome rather than a robust result.

If medicines management services are to be offered, patients should be given the choice to participate depending on their personal circumstances and preferences. Further research is needed to assess whether a medicines management service within cystic fibrosis can lead to a reduction in hospital admissions and medicines waste and to a sustained improvement in clinical outcomes.

About the authors

Emma J Frew, PhD, is senior lecturer in health economics at the University of Birmingham. Stirling Bryan, PhD, is professor of health economics at the University of British Columbia. Peter Spurgeon is professor of health services management at the University of Birmingham. Deirdre Doogan is director of government relations at Lloydspharmacy. Bettina Kluettgens, PhD, is service development manager at Lloydspharmacy. Baljit Ahitan, MRPharmS, is lead pharmacist — respiratory directorate, Birmingham Heartlands Hospital. Nicky Gilday is cystic fibrosis clinical development nurse at Birmingham Heartlands Hospital. David Honeybourne, FRCP, is consultant respiratory physician and honorary clinical reader at Birmingham Heartlands Hospital.

Correspondence to: Emma Frew, Department of Health Economics, Public Health Building, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT (tel 0121 414 3199; e-mail e.frew@bham.ac.uk)

References

- Yankaskas JR, Marshall BC, Sufian B, Simon RH, Rodman D. Cystic fibrosis adult care. Consensus Conference Report. Chest 2004; 125:1S-39S.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Pharmacy in the future. Medicines management. London: The Society, 2005 [documents no longer available].

- Royal Pharamaceutical Society. History of pharmaceutical care and medicines management. Managing medicines, a resource centre for medicines management and pharmaceutical care. London: The Society, 2002.

- Gee L, Abbott J, Conway SP, Etherington C, Webb AK. The development of a disease specific health related quality of life measure for adults and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 2000;55:946–54.

- Krska J, Hansford D, Jamieson D, Arris F, Cromarty JA, Abbot S et al. A classification system for issues identified in pharmaceutical care practice. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Practice 2002;10:91–100.

- Zermansky AG, Petty D, Raynor DK, Freemantle N, Vail A, Lowe C. Randomised controlled trial of clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly patients receiving repeat prescriptions in general practice. BMJ 2001;323:1340.

- Department of Health. High quality care for all: NHS next stage review final report. London: DoH, 2008.

- Department of Health. Management of medicines: a resource to support implementation of the wider aspects of medicines management for diabetes, renal and long term condition NSFs. London: DoH, 2004.

- Goodyer LI, Miskelly F, Milligan P. Does encouraging good compliance improve patients’ clinical condition in heart failure? British Journal of Clinical Practice 1995;49:173–6.

- Holland R, Lenaghan E, Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A et al. Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2005. Available at www.bmj.com (accessed 15 December 2009); doi:10.1136/bmj.333.67453.AE (published 24 January 2005).