Shutterstock.com

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Understand what Ramadan is and how to manage common queries from patients and colleagues during this time;

- Be aware of resources that can be used to assess or stratify and manage the effects of fasting for patients with certain medical conditions and taking certain medicines;

- Provide appropriate counselling to patients who are fasting and know when to refer complex cases.

Fasting from dawn to sunset during the month of Ramadan is one of the five pillars of Islam and is a time of increased spirituality for Muslims through reflection, devotion and prayer[1]. Fasting includes refraining from eating, drinking, smoking, sexual activity and taking oral medications. Ramadan is the ninth month in the Islamic lunar calendar; in 2022, it will begin in the evening of 2 April and will continue until the evening of 1 May. However, the start date can vary owing to the nature of the lunar calendar and is usually around 11 days earlier than the previous year each year[2].

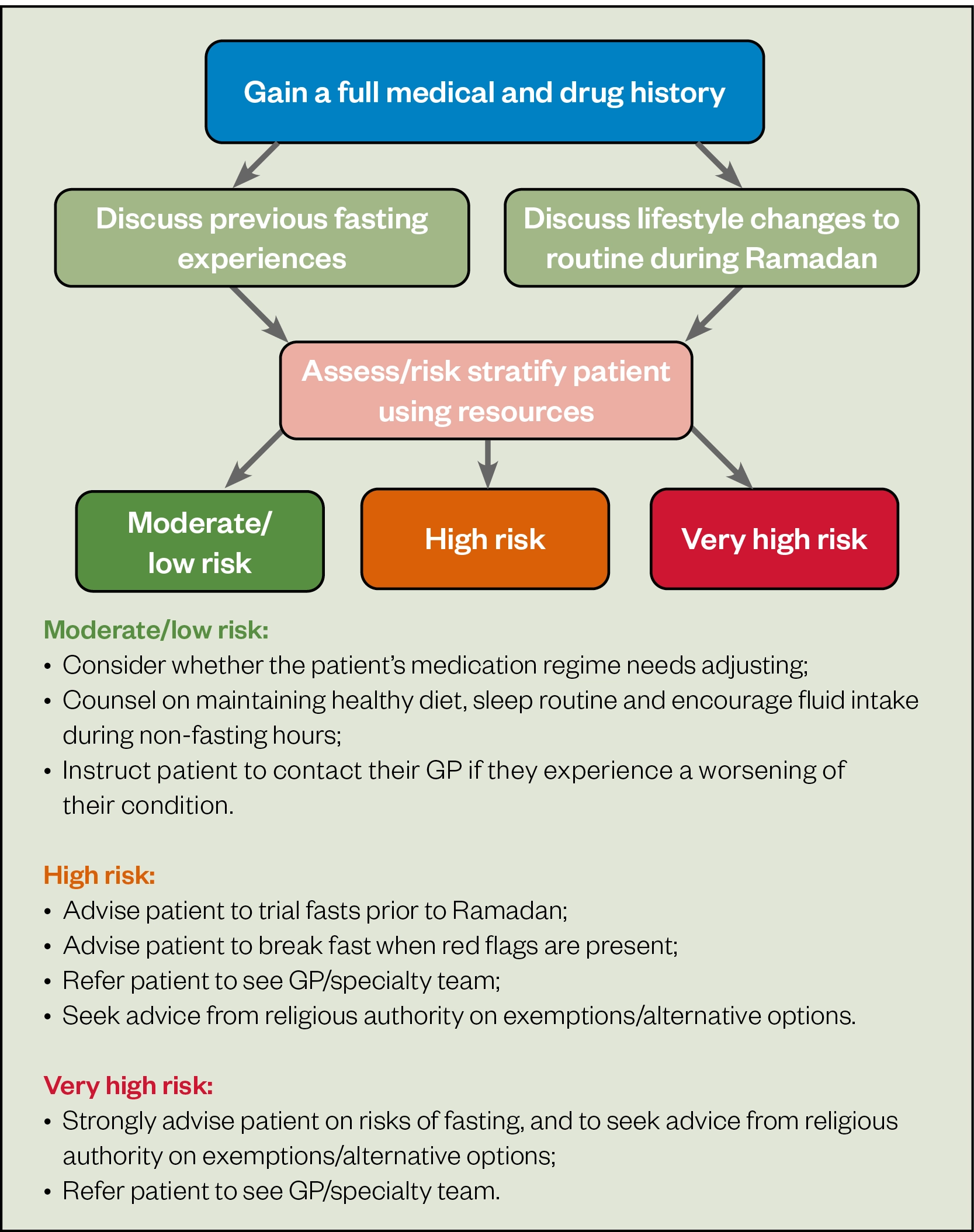

A worldwide survey estimates that around 93% of Muslims fast during Ramadan[1]. It is important for pharmacists to advise and support patients on how to manage medicines safely and effectively during this time. Patients with pre-existing medical conditions should be advised to consult with their doctor, pharmacist or specialty teams at least three to four weeks prior to Ramadan to review their condition and any treatment. For more information, see visual summary on ‘Ramadan fasting with existing conditions’[3,4].

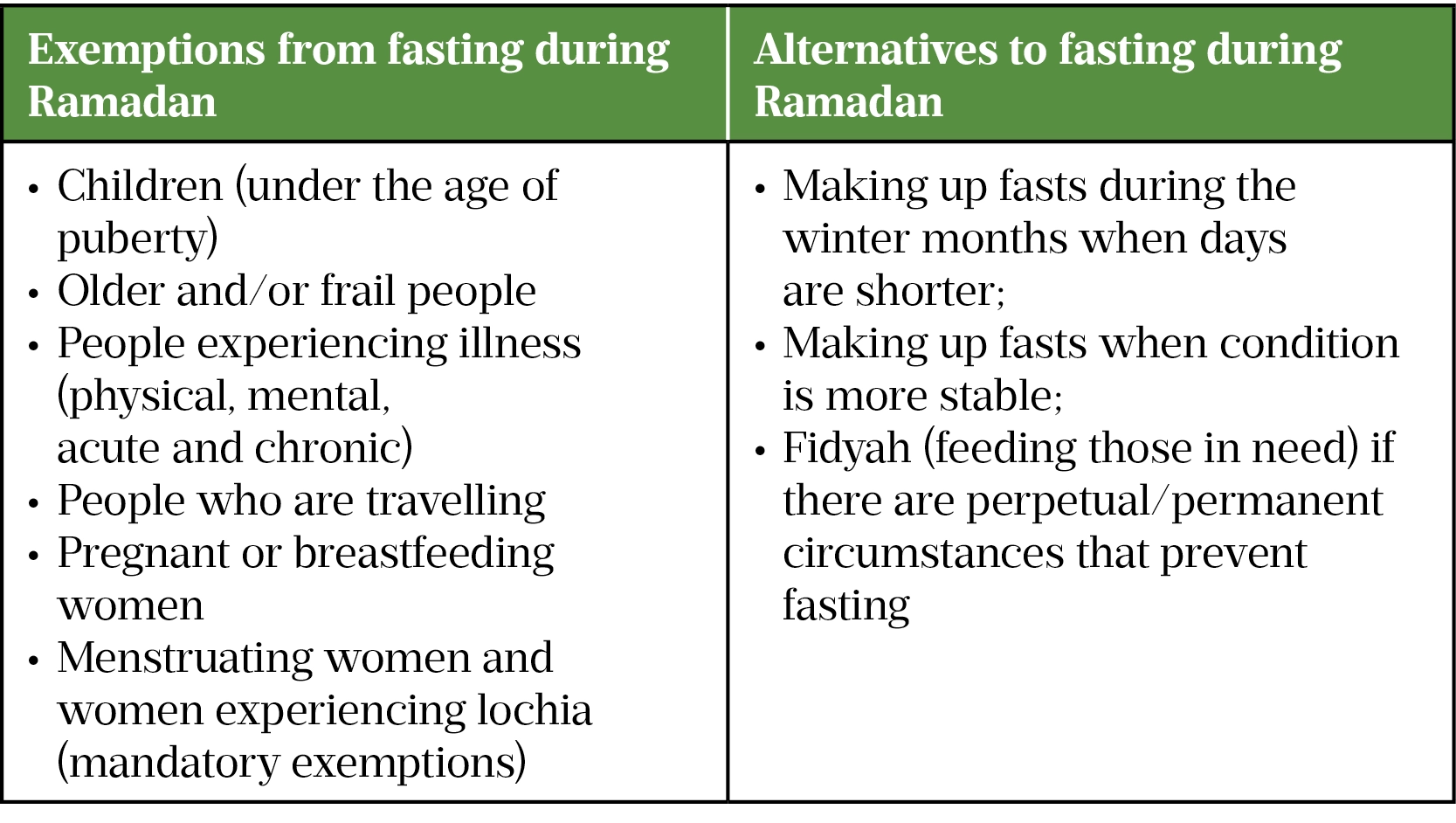

Exemptions and alternatives

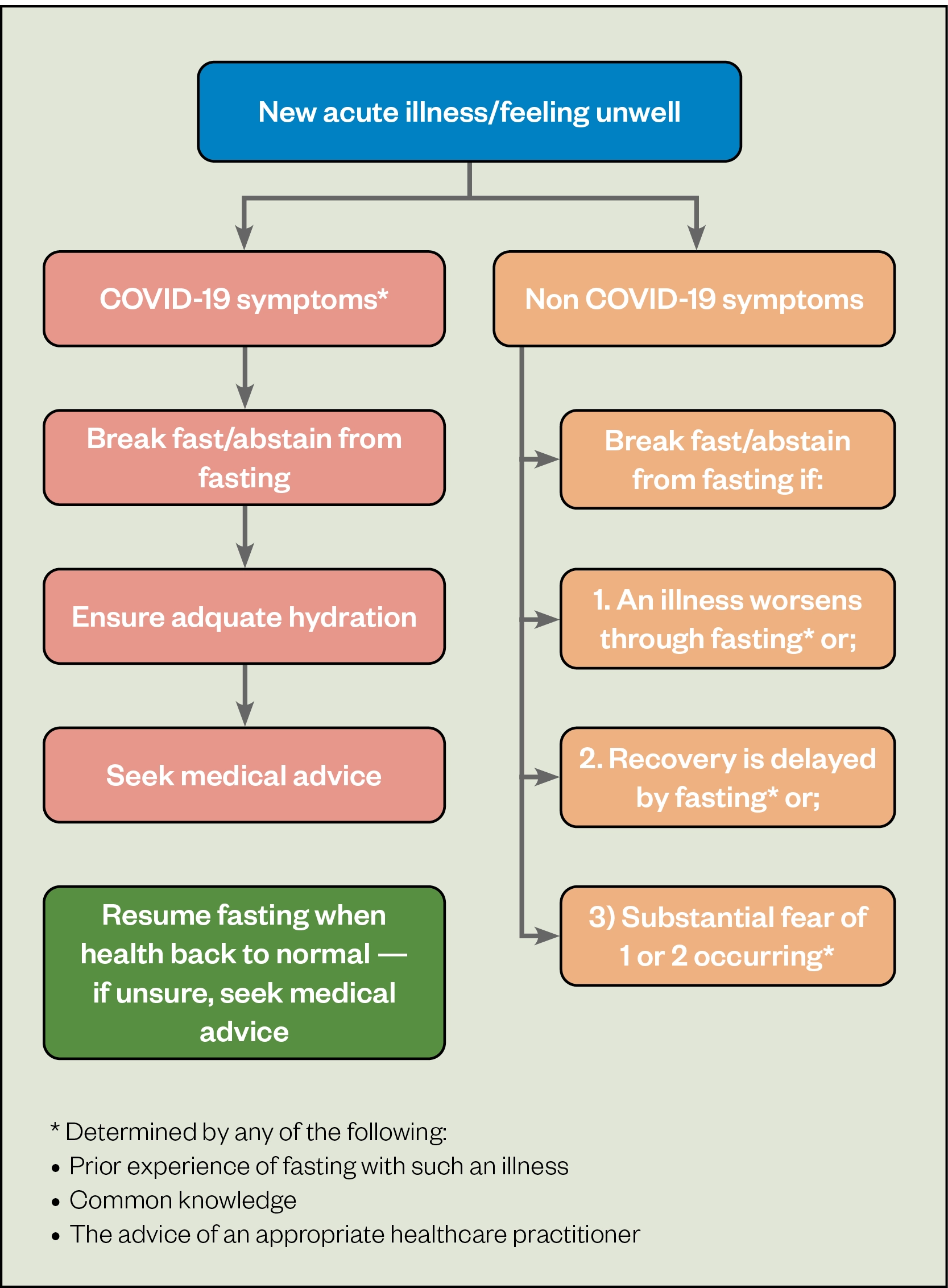

Diabetes is one of the conditions that carries greater risk for people when fasting. Studies estimate that globally 63.6% of patients with type 2 diabetes fast daily during Ramadan and 94.2% fast for at least 15 days[5]. When a patient has a chronic condition (e.g. diabetes, heart failure) or an acute illness (e.g. a urinary tract infection [UTI] or COVID-19) that will be worsened by fasting or delay recovery, they are exempt from fasting until their condition has stabilised[1]. Some patients will fast despite being exempt (see Box 1) owing to the desire to engage in spirituality and seek blessings along with their community and families. An extended list of affected conditions and how risk can be stratified in each case can be found in the British Islamic Medical Association (BIMA) Ramadan Compendium.

Exempt patients should be signposted to a religious authority (e.g. imam or scholar) who they trust for further information and advised that there are alternative options to fasting during Ramadan (see Box 2).

Pharmacists should advise patients on the risks and individualised alternatives of fasting; however, if they decide to fast against medical advice, patients should still be supported with adequate monitoring suitable for their condition.

Counselling advice

Medication regimes will be affected by changes to routine during Ramadan, such as adjusted sleep patterns to wake up for the pre-dawn meal and the inability to take medication orally during daylight hours, both of which may result in compliance issues. Pharmacists should reinforce to patients the importance of still taking their medications and counsel on management techniques during non-fasting hours. Pharmacists can advise on the risks of fasting individualised to each patient and make them aware that if they are exempt, alternatives to fasting do exist (see Box 2). All healthcare professionals should understand the importance of having discussions with patients in the run up to Ramadan to educate and support them in managing their medicines. For patients with diabetes, this would include recommending medication adjustments (see Case 2) or counselling patients to avoid the potential side effects of fasting, such as hypoglycaemia, hypotension and dehydration. Additional counselling points can be found in ‘How pharmacists can support and advise patients during Ramadan’ and Figure 1.

Pharmacists can contact a patient’s physician where necessary to make any required changes to their medication regimen before Ramadan starts. Medication should not be stopped or altered without first being discussed with a pharmacist or doctor[7]. The decision to fast ultimately lies with the patient, and it is a pharmacist’s professional duty to explain the risks based on the patient’s condition and/or medication, so that they can make a fully informed decision.

The three cases discussed below will cover how consultations around fasting can be approached for UTIs, diabetes, and hypothyroidism in a variety of settings, allowing for practical application of the available guidance.

Case 1: Urinary tract infection

A female aged 23 years collects a prescription for trimethoprim 200mg twice daily for 3 days to treat an uncomplicated lower UTI. She asks to speak to the community pharmacist for advice on fasting with this medication.

Consultation

As seen in Figure 1, any other medications the patient is taking and any other medical conditions they have should be confirmed, as well as the patient’s previous experiences of fasting. In this case, the patient is taking no other medicines, including over-the-counter medicines and herbal remedies, and has no other significant or relevant past medical history. She confirms that she has no allergies and is not pregnant. She manages Ramadan well apart from some fatigue towards the end of the fast.

Management advice

The antibiotics that the patient has been prescribed allow a pre-dawn and sunset dose to be taken, if around 8–12 hours apart. If fasting exacerbates an active infection or delays recovery, this could lead to complications, such as an ascending infection — potentially leading to pyelonephritis, impaired renal function, sepsis, recurring infections and antibiotic resistance caused by repeated antimicrobial use[8–10]. These risks must be communicated to the patient.

Although guidelines on specific volumes are lacking, adequate hydration and fluid intake are recommended in the management of UTIs[9]. This is especially important in the presence of infection; therefore, pharmacists should encourage enough fluid intake to avoid dehydration[11], which could be difficult to achieve during the fasting hours. Common side effects of trimethoprim include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea, all of which can cause dehydration[12]. The hydration levels of fasting patients who experience these adverse effects is already compromised owing to reduced fluid intake. As per the BIMA Ramadan Compendium recommendations on acute illness (see Figure 2), this patient should be advised to break the fast or abstain if their condition worsens or recovery is delayed, and to speak to their doctor if this occurs[13]. In this case, the patient should be given the choice to fast but should be advised of the alternatives (see Table), along with a discussion with the pharmacist about the risks to enable the patient to make an informed decision.

Case 2: Diabetes

A male aged 57 years with type 2 diabetes, hypertension and glaucoma is admitted to hospital with severe hypoglycaemia. The medical team request advice from the specialist diabetes pharmacist on how to manage his medicines as the patient intends to fast during Ramadan.

Consultation

The pharmacist should review the patient’s drug history, inpatient drug chart, medical notes, bloods and observations, and the consultation should follow the steps outlined in Figure 1. The patient explains that this is their first Ramadan since being diagnosed with diabetes the previous year.

The patient was taking the following medicines prior to admission: metformin 1g twice daily; gliclazide modified release 30mg once daily; ramipril 10mg once daily; atorvastatin 20mg once daily; and latanoprost 50micrograms/mL eye drops — one drop in the affected eye(s) at night. It is noted that the patient has recent admissions for hypoglycaemia over the past few months.

Management advice

As per the BIMA Ramadan Compendium risk stratification table, the patient would be classified as very high risk, owing to severe hypoglycaemia occurring within the three months prior to Ramadan, and should be advised not to fast[13]. Possible risks of fasting for this patient, including hypoglycaemia and dehydration, should be explained and the patient should be reassured that there are alternative options (see table). The patient should be advised to consult with his GP or diabetes nurse before he considers fasting in the future to assess if it is safe for him to do so, dependent on his diabetes control at that time. After discussion with his doctor or diabetes nurse, the patient could consider trial fasting before next Ramadan and documenting the experience to assist in future pre-Ramadan consultations. If the patient requires further reassurance, the hospital chaplain could visit them and talk through the alternatives, while reassuring him that missing fasts owing to the risks to his health is in accordance with the teachings of Islam.

If the patient decides to fast despite the risks, extreme caution should be advised and they should be encouraged to seek the opinion of a trusted religious authority to discuss exemption from fasting. The consultation should be clearly documented in the medical notes regarding the advice not to fast (and the reasoning for this), as well as that the patient is choosing to fast despite medical advice. While fasting, their health should be monitored either by a specialist or primary care team. The patient should be advised to break the fast in the event of red flag symptoms for their condition (e.g. symptoms of hypoglycaemia [fatigue, dizziness], dehydration or out-of-range blood glucose levels). A common misconception may be that finger prick blood glucose testing invalidates fasting. However, this is not the case and patients should be advised to check levels regularly throughout the day[14]. This advice helps mitigate — but does not remove — the risk. If appropriate, medication doses and timing should also be adjusted as per existing guidelines[15,16]. This patient is on once-daily and twice-daily medications that can be split between the meal at the time of breaking fast (iftar) and the pre-dawn meal (suhoor). Additionally, the patient is using latanoprost eye drops that should, preferably, be administered in the evening and can be administered after the fast breaks[17]. However, there is a difference in opinion between Islamic schools of thought on if the administration of some routes of medications break the fast (e.g. the majority agree that inhaled and intravenous medication break the fast)[4].

Case 3: Hypothyroidism

During a structured medication review with a primary care pharmacist in a GP practice, a female aged 35 years with hypothyroidism and iron deficiency anaemia asks if she is still able to fast while on medication, and for assistance managing her medication.

Consultation

The patient’s records show that she is currently prescribed levothyroxine 100 micrograms every morning and ferrous sulfate 200mg twice daily. During her review, she states that she does not use any other medication, including herbal products and over-the-counter medicines.

Figure 1 can be used to inform the consultation. The patient’s recent thyroid-stimulating hormone result is in range and her full blood count, although showing borderline low haemoglobin, has been stable for the past year. The patient’s wellbeing and day to day symptoms should be enquired. The patient states that she occasionally feels fatigued. She managed previous fasts by resting and sometimes taking small naps after work.

Management advice

The patient would be classified as low risk owing to stabilised treatment, bloods and previous experience in fasting, and should be advised that it is safe for her to fast as her conditions are stable. Furthermore, her medications do not have any major side effects that may be exacerbated by fasting and the timings can be adjusted to facilitate fasting. As ferrous sulfate can reduce the absorption of levothyroxine, the patient should be advised to leave a two-hour gap between them[18,19]. Although iron preparations are best absorbed on an empty stomach, to reduce gastrointestinal side effects they can be taken with or after food[20]. Therefore, a dose of ferrous sulfate can be taken both with suhoor and iftaar. The medication should not be taken with egg, tea or milk as absorption can be impaired[18]. Levothyroxine is recommended to be taken before breakfast or the first meal of the day to optimise absorption; in this case, the patient should be advised to take levothyroxine at least two hours after food (e.g. after iftar or 30 minutes before suhoor)[19].

Once timing of the doses is agreed with the patient, they can be reassured that it is safe to fast while on the current medication. However, if there are any changes to her symptoms or she experiences a change in health, the patient should contact a GP or pharmacist, and should not stop any prescribed medicines without a consultation.

Conclusion

Pharmacists should advise patients on how to adjust medicines to optimise health outcomes and provide tailored counselling on whether fasting is appropriate in the month of Ramadan. This article should be read in conjunction with the resources below, but these do not replace clinical judgement and each patient should be reviewed on a case-by-case basis.

Additional resources

It is highly recommended the following resources are read in conjunction with the above article and used as references when advising on how to manage medicines during Ramadan:

- BIMA Ramadan Compendium 2021

- Advising patients with existing conditions about fasting during Ramadan

- How to manage diabetes during Ramadan

- Medicines, Healthcare and the Holy Month of Ramadan

- How pharmacists can support and advise patients during Ramadan

- Is it safe for patients with COVID-19 to fast during Ramadan?

- Diabetes and Ramadan

- Fasting with adrenal sufficiency

Health inequalities

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s policy on health inequalities was drawn up in January 2023 following a presentation by Michael Marmot, director of the Institute for Health Equity, at the RPS annual conference in November 2022. The presentation highlighted the stark health inequalities across Britain.

While community pharmacies are most frequently located in areas of high deprivation, people living in these areas do not access the full range of services that are available. To mitigate this, the policy calls on pharmacies to not only think about the services it provides but also how it provides them by considering three actions:

- Deepening understanding of health inequalities

- This means developing an insight into the demographics of the population served by pharmacies using population health statistics and by engaging with patients directly through local community or faith groups.

- Understanding and improving pharmacy culture

- This calls on the whole pharmacy team to create a welcoming culture for all patients, empowering them to take an active role in their own care, and improving communication skills within the team and with patients.

- Improving structural barriers

- This calls for improving accessibility of patient information resources and incorporating health inequalities into pharmacy training and education to tackle wider barriers to care.

- 1Most Muslims say they fast during Ramadan. Pew Research Center. 2019.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/07/09/global-median-of-93-of-muslims-say-they-fast-during-ramadan/ (accessed Mar 2022).

- 2Ramadan. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2022.https://www.britannica.com/topic/Ramadan (accessed Mar 2022).

- 3Visual summary: Ramadan fasting with existing conditions. BMJ. 2022.https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/376/bmj-2020-063613/F1.large.jpg?width=800&height=600 (accessed Mar 2022).

- 4Mahmood A, Dar S, Dabhad A, et al. Advising patients with existing conditions about fasting during Ramadan. BMJ 2022;376:e063613. doi:10.1136/bmj-2020-063613

- 5Babineaux S, Toaima D, Boye K, et al. Multi-country retrospective observational study of the management and outcomes of patients with Type 2 diabetes during Ramadan in 2010 (CREED). Diabet Med 2015;32:819–28. doi:10.1111/dme.12685

- 6Elnakib S. Ramadan The Practice of Fasting. eat right. 2021.https://www.eatright.org/health/lifestyle/culture-and-traditions/ramadan–the-practice-of-fasting#:~:text=Children%20who%20have%20not%20reached,gum%2C%20from%20dawn%20to%20sunset (accessed Mar 2022).

- 7Bukhari N. How pharmacists can support and advise patients during Ramadan. The Pharmaceutical Journal. 2016.https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-pharmacists-can-support-and-advise-patients-during-ramadan (accessed Mar 2022).

- 8Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol 2010;7:653–660. doi:10.1038/nrurol.2010.190

- 9Urinary-tract infections. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/urinary-tract-infections.html#:~:text=Patients%20with%20a%20UTI%20should%20be%20advised%20to,not%20delaying%20urination%2C%20and%20not%20wearing%20occlusive%20underwear (accessed Mar 2022).

- 10Complications | Urinary tract infection (lower) — women. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2021.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/urinary-tract-infection-lower-women/background-information/complications/ (accessed Mar 2022).

- 11Trimethoprim — side effects. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/trimethoprim.html#sideEffects (accessed Mar 2022).

- 12Scenario: UTI – (no visible haematuria, not pregnant or cathetirized). National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2022.https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/urinary-tract-infection-lower-women/management/uti-no-visible-haematuria-not-pregnant-or-catheterized/ (accessed Mar 2022).

- 13Ramadan Compendium. British Islamic Medical Association. 2021.https://britishima.org/ramadan/compendium/ (accessed Mar 2022).

- 14Jaleel M, Raza S, Fathima F, et al. Ramadan and diabetes: As-Saum (The fasting). Indian J Endocr Metab. 2011;15:268. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.85578

- 15Moursi A. Medication management during Ramadan. Corporate Pharmacy Department Drug Information Center. 2022.https://www.tamesideandglossopccg.org/getmedia/8daaf6d5-f57a-4793-b72d-63aa0c9af5dd/Ramadandruginfo (accessed Mar 2022).

- 16Gilani A. How to manage diabetes during ramadan. Diabetes and Primary Care. 2022.https://diabetesonthenet.com/wp-content/uploads/Gilani_Ramadan_2022-revision.pdf (accessed Mar 2022).

- 17Latanoprost. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/latanoprost.html (accessed Mar 2022).

- 18Ferrous sulfate 200mg coated tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2022.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3130 (accessed Mar 2022).

- 19Levothyroxine 100 microgram tablets. Electronic medicines compendium. 2021.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/12781 (accessed Mar 2022).

- 20Ferrous sulfate. British National Formulary. 2022.https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/ferrous-sulfate.html (accessed Mar 2022).

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

For mental health medicines the Choice and Medication website portals have a series of leaflets on mental health medicines, also available in Arabic, Bengali, Hindi, Somali, Turkish, and Urdu.