Abstract

Aim

To determine the views, experiences and attitudes of pharmacists in Scotland towards Royal Pharmaceutical Society branches. To identify facilitators and barriers to branch meeting attendance. To explore future preferences.

Design

Postal questionnaire.

Subjects and setting

A random sample of 1,000 members of the Society resident in Scotland.

Results

404 pharmacists responded. Of these, 76% had not attended any meetings in the previous year. Pharmacists registered for more than 20 years were more likely to attend branch meetings. Area of practice was a factor with those working for multiples least likely to attend. Participants held largely positive views about the roles of the branch but somewhat negative views about the value of their current branch programmes.

Conclusion

Members do not engage with the branches; this could be a problem for the new professional body. Innovative approaches may be required to encourage pharmacists to participate in the proposed new local practice forums and benefit from the support these could provide.

The local branches of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain have provided support, education and networking opportunities for members since their inception. There are currently 130 branches in Britain, including 12 in Scotland.

In recent years the role of the community pharmacist in particular has changed, partly as a result of NHS policy across the UK1–3 to include contracts around specific services such as medication review, public health and minor ailments. Pharmacists are being asked by patients, the NHS and by the Government to take on new and challenging responsibilities, which may require different ways of thinking and working. Peer support for these new roles is vital; arguably, pharmacists have never been more in need of peer support and networking opportunities, while the need for education and training is ongoing.4 The Society’s local branch network was established in 1922, partly to meet these needs.5 Anecdotally meeting attendance at some branches is poor and some are inactive.

In 2007 the UK Government published “Trust, assurance and safety: the regulation of health professionals”,6 a White Paper setting out changes to the regulation of the profession of pharmacy, among others. In 2010, the roles of the Society will separate: the regulatory function will pass to a new body, the General Pharmaceutical Council, and the professional function will be taken on by a new professional body for pharmacy, the structure and membership of which is currently a subject of much debate. The Transitional Committee (Transcom) has recently proposed that the new body should include “opportunities for members coming together at a local or regional level to benefit from shared professional experiences”,7 and is currently seeking feedback from pharmacists on these and other proposals.

This study was carried out as part of the undergraduate MPharm course at the School of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, Robert Gordon University (RGU), Aberdeen. The aims were to determine Scottish pharmacists’ views, experiences and attitudes towards Society branches, identify facilitators and barriers to branch meeting attendance and explore future preferences regarding a local network for professional support.

Method

A questionnaire was developed based on the published literature and the (then) Society byelaws.8 It was reviewed for face and content validity by an expert panel of six experienced academic pharmacy practitioners and researchers, including four members of the Society’s Scottish Pharmacy Board (SPB). Ethics approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee, the School of Pharmacy, RGU; the local NHS Research Ethics Committee confirmed that full submission for ethics approval was not required.

The questionnaire was piloted on a random sample of 100 members of Society in Scotland in August 2007. A letter inviting participation and stating the research background and aims was included with each questionnaire. Piloting resulted in one minimal change. Data from the pilot sample were not included in the final study.

The final version of the questionnaire was sent by post in November 2007 to the registered addresses of a random sample of 1,000 members of the Society in Scotland, provided by the Society (approximately 25 per cent of members resident in Scotland). Personally addressed envelopes containing the questionnaire, covering letter and reply-paid envelope were sent; up to two reminders were sent to non-respondents at two-weekly intervals. Members of the SPB were excluded as were those who participated in the pilot. There were no other exclusions.

The questionnaire contained items on: respondents’ demographics and branch attendance; facilitators and barriers to attendance; methods of branch communication; and views and attitudes of respondents towards the functions and activities of the branches. Open and closed questions were used to elicit responses and respondents were also asked to use five-point Likert scales to rate their level of agreement with statements on appropriate roles for the branches, derived from the then Society Byelaws,8 and with statements regarding attendance at branch meetings.

Data were coded and entered into SPSS for Windows version 13 (SPSS Inc) and analysed using descriptive statistics. Chi squared tests and Mann Whitney tests were used to test for variables associated with branch attendance factors and P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Content analysis was performed on the responses to the open question relating to comments, issues or concerns around Society branches.9 All emerging themes and quotes were discussed and agreed by the research team; key themes are described with illustrative quotes.

Results

A total of 404 questionnaires were returned giving a response rate of 40.4 per cent. Most respondents were female (n=265, 65.6 per cent), practising pharmacists (n=356, 88.1 per cent) and community pharmacists (n=209, 51.7 per cent). Other areas of practice were hospital (n=87, 21.5 per cent), primary care (n=33, 8.2 per cent) and “other” (n=16, 4.0 per cent).The most common age groups were 25–34 years (n=94, 23.3 per cent), 35–44 years (n= 114, 28.2 per cent) and 45–54 years (n=98, 24.3 per cent).

Attendance at branch meetings

Some 307 respondents (76.0 per cent) had not attended any meetings in the previous year. Of the remaining 86 respondents, 31 (36.0 per cent) had attended all or most meetings.

Pharmacists registered for more than 20 years were significantly more likely to attend branch meetings (n=190, 47 per cent; P<0.01, chi-squared test), as were pharmacist prescribers, preregistration tutors and branch committee members or office bearers (n=130, 32.2 per cent; P=0.001, chi-squared test).

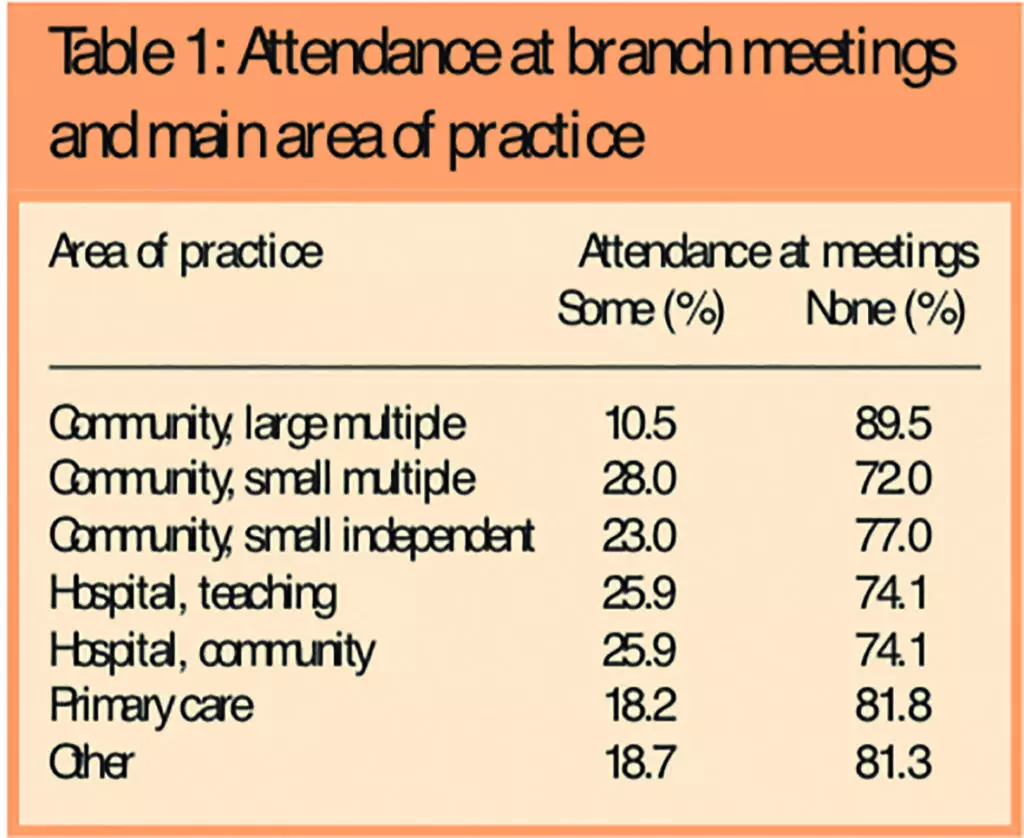

Although attendance was low across all sectors of the profession, area of practice did make a difference, with those working for the large multiples least likely to attend (P<0.05, chi-squared test) when compared with all other sectors (Table 1).

The results possibly suggest that possession of a postgraduate qualification (ranging from postgraduate certificate to PhD) was a predictor of attendance at branch meetings although this relationship did not reach statistical significance (n=155, 38.4 per cent; P=0.054, chi-squared test). The same was found for participation in other pharmacy-related events such as NHS Education for Scotland (NES) pharmacy events, other continuing education courses, pharmacy-related conferences and Community Health Partnership meetings (n=293, 72.5 per cent; P=0.077, chi-squared test).

Roles for the branches

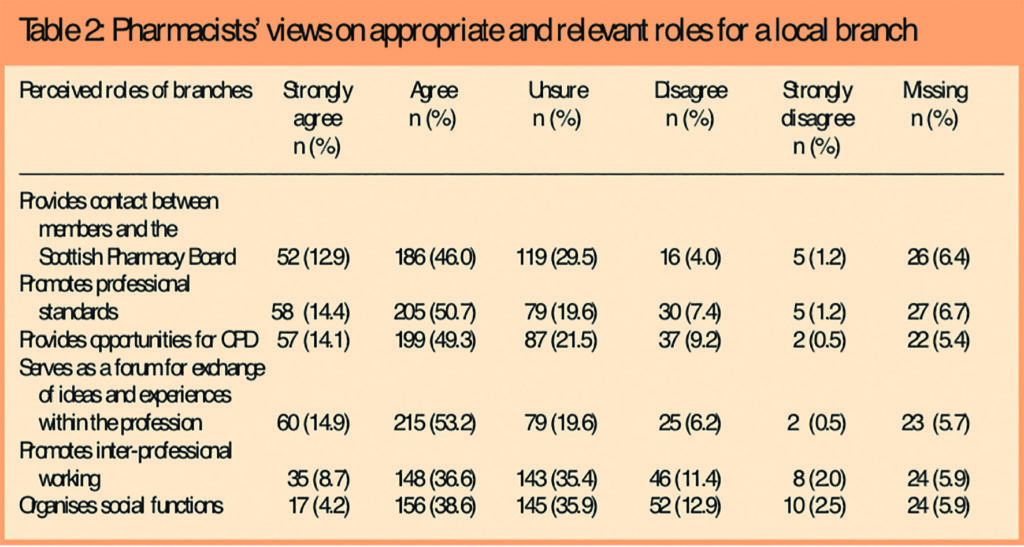

The study sought to explore pharmacists’ views on appropriate, relevant roles for a local branch. Various statements regarding possible roles were derived from the (then) current branch Byelaws.8 Table 2 shows pharmacists’ levels of agreement or disagreement with these statements (n=404).

It can be seen that participants held largely positive views about these roles. In particular, the roles of the branch network in facilitating communication between members and the SPB and in promoting professional standards were identified as appropriate, as were provision of opportunities for continuous professional development and for exchange of ideas and experiences within the profession.

Pharmacists’ views on branch meetings

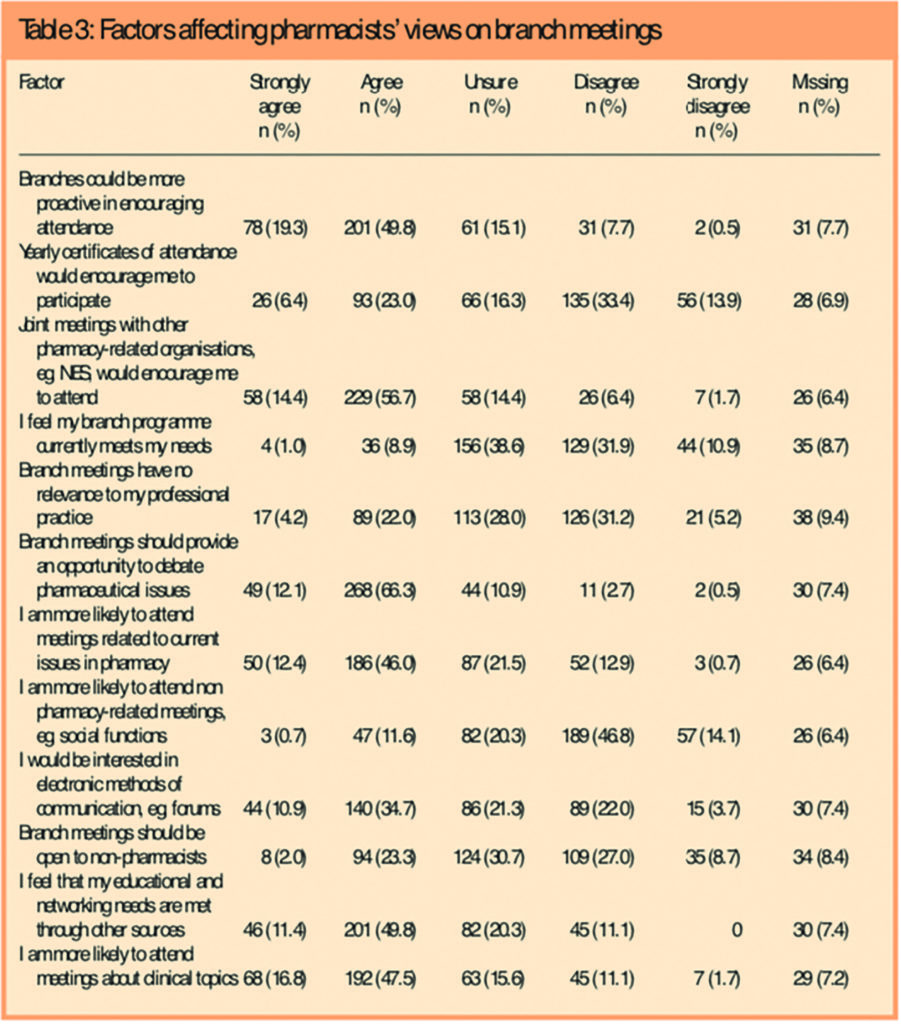

The final section of the questionnaire was designed to examine pharmacists’ feelings about attending branch meetings, and the factors affecting these feelings. Table 3 shows pharmacists’ levels of agreement or disagreement with statements put to them (n=404). It can be seen that respondents were somewhat negative about the value of their current branch programme, believing that their educational and networking needs were met by other sources. However respondents were more positive about the opportunities offered by the branch network to debate current issues, and would welcome joint meetings with, for example, NES Pharmacy.

Most pharmacists had to travel to attend branch meetings; both distance from work to venue (P<0.05, Mann Whitney test) and from home to venue (P<0.05, Mann Whitney test) were inversely related to attendance. A typical comment was “Just too far to travel after a full day at work”; 110 respondents (27.2 per cent) were willing to travel more than 10 miles to attend meetings.

The questionnaire included several opportunities for comment on various aspects of the branches.The most common theme identified (117 comments) was the perceived relevance or interest of the meeting topic. Respondents were seldom specific but where they were they tended to focus on a desire for more educational and clinically based topics, opportunities for networking and debate or discussion of current pharmacy topics. Most respondents simply made a comment about wanting “relevant, interesting” topics, implying or indeed stating, “I don’t feel that they are particularly relevant or helpful to me”. Some respondents said that the provision of “topics which can be included in CPD” or “certified CPD hours (on clinical topics)” would possibly increase their attendance.

Most pharmacists reported juggling work and other commitments; 34 comments were made identifying these as barriers to attendance with 15 respondents giving family responsibilities as the reason for their non-attendance at meetings. A typical comment was “Pressure of work and life balance plays a big part in my decision to attend or not”.

Sixteen pharmacists commented that better notification of meetings might possibly increase attendance. Among those who replied to this question (n=309), e-mail was the most favoured means of branch communication (n=130, 42.1 per cent) with post somewhat less popular (n=90, 29.1 per cent). A further 82 respondents (26.5 per cent) would be happy with electronic means (ie, e-mail, website) or post. Only 7.2 per cent of respondents thought that their branch had a website, with 74 per cent unsure.

Just over half of respondents (n=220, 54.4 per cent) remembered seeing the most recent branch programme. When asked for their opinions on branch communication, there were 13 positive comments such as “our local secretary is very good” and 30 more negative ones such as “branch communication is very scarce and does not entice me to go after a full day’s work”.

Interpersonal communication at meetings was perceived as poor, with 24 comments on factors such as “lack of friendliness from current members” and “clique attitude of regular attendees” acting as barriers.

Respondents were somewhat negative about the relevance of their local branch to their professional practice, yet 33 comments were made identifying that the branch network could provide a professional and networking forum. One representative said: “I think that providing opportunities for pharmacists (especially from different sectors) to get to know each other is important. They should actually enable that. Meetings are daunting if you know no one.” Another said branches could “provide [a] forum for interactive discussion on topical issues”.

Discussion

Key findings of this research were that pharmacists in the main were not attending local Society branch meetings. This applied across the profession but was particularly evident for those community pharmacists employed by the large multiples. Pharmacists registered for more than 20 years were significantly more likely to attend meetings as were those pharmacists taking on roles such as pharmacist prescribers, preregistration tutors and branch committee members or office bearers. This non-attendance is particularly relevant as pharmacy moves towards the formation of a new professional body.

This research has several strengths and weaknesses. As far as is known to the researchers, this is the first Scotland-wide study of members’ views, experiences and attitudes towards the branches of the Society and their functions. Care is needed in interpreting the findings given the response rate of 40.4 per cent and geographical location of the survey in Scotland, which limit generalisability. However, respondents’ demographics were found broadly to match those of UK10,11 or, where specifically available, pharmacists in Scotland.11 No attempt was made to check the validity or reliability of data, which may have been influenced by recall bias and non-response bias.

Our study was carried out at a time of uncertainty within the profession and the data collection period coincided with the announcement of a substantial rise in retention fees. This may have coloured respondents’ views, but the fact that so few attended any meetings at all within the previous year suggests that members’ lack of engagement with their local branches is more long-standing.

In particular, respondents were somewhat negative about the value of their current branch programme, believing that their educational and networking needs were met by other sources. However, they were more positive about the opportunities offered to debate current issues and appeared to be in agreement with many of the roles of the branch network as highlighted in the (then) current Byelaws8 and echoed in the new principles for running a Society branch and branch committee.12 Respondents placed less emphasis on interprofessional working, and much less emphasis on the social functions of the local branch network. The desire for opportunities for debate, discussion and networking should be incorporated into the local structure of the new professional body if it wants to deliver on professional issues and support.

Several barriers to attendance were identified, chief among which was a perceived lack of relevance to members’ professional practice; it appears that the local branch network is not meeting the requirements of large numbers of members in terms of professional practice, and is not perceived as functioning in terms of provision of CPD opportunities. As the profession moves towards the formation of a new professional leadership body these deficiencies must be addressed.

Despite the barriers to meeting attendance identified by respondents, most (n=307, 75.9 per cent) attended NES Pharmacy events, suggesting that such barriers can be overcome. In order to encourage attendance, local branches could consider joint meetings with organisations such as NES Pharmacy (favoured by 71.1 per cent of respondents) and providing opportunities to debate current issues in pharmacy. One Scottish branch already holds such joint meetings.

Communication between the branches and members can be problematic, although the fact that three Scottish branches were inactive at the time of the study may have contributed to the number of respondents who reported receiving no communication from their branch. It may be that utilising branch websites or similar virtual spaces to publicise meetings, display presentations and to host discussion forums would help overcome barriers such as lack of time and distance from meetings.

The perception that branch meetings are “unfriendly” and “like a middle-aged members’ club” needs to be addressed; one of the messages from this survey is that in addition to providing “interesting, relevant topics” the branches need to be more proactive and welcoming in order to encourage attendance. There appear to be particular issues with the attendance of younger pharmacists and those working for the large multiples and further research is needed in these areas.

Members’ lack of engagement with the branches is a problem for the Society and could continue to be so for the new professional body that will soon come into being. Innovative approaches may be required to encourage more pharmacists to participate in the proposed new local practice forums and benefit from the support these forums aim to provide.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Gráinne McDermott, Isla Stewart and Maria Veart for help with data collection, Linda Adams for administrative support and Christine Bond, Lyndon Braddick and Rose Marie Parr for advice.

About the authors

Trudi McIntosh, BSc, MRPharmS, and Kim Munro, MSc, MRPharmS, are lecturers and Derek Stewart, PhD, MRPharmS, is a senior lecturer in the School of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen

Correspondence to: Trudi McIntosh, School of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, Robert Gordon University, Aberdeen AB10 1FR (e-mail t.mcintosh@rgu.ac.uk)

References

- Scottish Executive. The right medicine: a strategy for pharmaceutical care in Scotland. Edinburgh: The Executive; 2002.

- Department of Health. Pharmacy in the future: implementing the NHS plan. London: DoH; 2000.

- Welsh Assembly Government. Remedies for success: astrategy for pharmacy in Wales. Cardiff: WAG; 2002.

- Pfleger DE, McHattie LW, Diack HL, McCaig DJ, Stewart DC. Developing consensus around the pharmaceutical public health competencies for community pharmacists in Scotland. Pharmacy World and Science 2008;30:111–9.

- Hudson B. The evolution of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Available at: www.rpsgb.org.uk/pdfs/ musevb1.pdf (accessed 1 February 2009).

- Department of Health. Trust, assurance and safety: the regulation of health professionals in the 21st century. London: DoH; 2007

- Transitional Committee. The new professional body for pharmacy. The Prospectus. London: Transcom; 2008.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Byelaws. Available at: www.rpsgb.org/pdfs/byelaws.pdf (accessed 18 June 2008)

- Glaser, BG, Strauss, AL. The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago: Aldine; 1967.

- Hassell K, Seston L, Eden M. Pharmacy workforce census 2005. Manchester: University of Manchester; 2006.

- Seston E, Hassell K, Schafheutle E. Workforce update — joiners, leavers and practising and non-practising pharmacists on the 2007 Register. Pharmaceutical Journal. 2007; 279:691–3.

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. Principles for running an RPSGB branch and branch committee. Available AT: www.rpsgb.org/pdfs/brmprinciples.pdf (accessed 29 January 2009)