Shutterstock.com

In 2017, 5,821 suicides were recorded in the UK[1]

, while around 1 in 15 (6.7%) adults in England are estimated to have attempted suicide at some point in their life[2]

.

The Office for National Statistics defines suicide as all deaths from intentional self-harm for people aged 10 years or over, and deaths where the intent was undetermined for people aged 15 years and over[1]

. Self-harm is different from suicide in that it is a much broader category that covers any deliberate self-injury and occurs in the presence and absence of suicidal intent[2]

.

This article details how psychological models can be applied to help pharmacy professionals deal with suicide disclosure effectively and recognise warning signs in clinical settings.

Who is at risk?

Suicide is the leading cause of death for women aged 24–30 years and men aged under 50 years in England and Wales — 75% of people who died by suicide in 2017 were male[1]

. Around 90% of people dying by suicide have a psychiatric disorder[3]

, although this may not have been formally diagnosed or treated. Depression is the most common disorder, found in at least 60% of cases of death by suicide[3]

.

Findings from the Centre for Suicide Research at the University of Oxford report that healthcare professionals working across all sectors will encounter depressed people who may be at risk. Around 50% of people who take their own lives will have seen a GP in the three months before death; 40% in the month beforehand; and around 20% in the week before death. Healthcare professionals working in primary care, particularly pharmacists, are therefore vital in the detection and management of people at risk of suicide[4]

.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence is currently in the process of developing a quality standard on suicide prevention, scheduled for publication in September 2019, which will cover ways to reduce suicide and help people bereaved or affected by suicides in community and custodial settings[5]

.

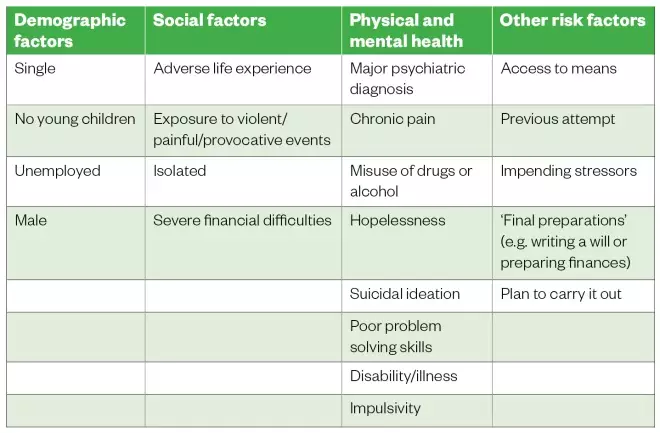

Contributing risk factors and warning signs

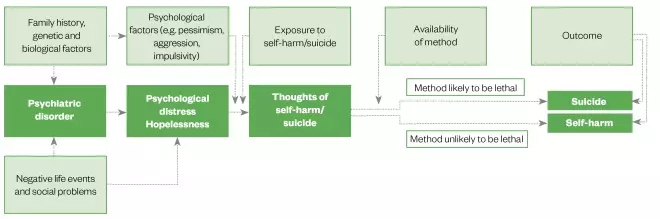

Suicide can be the result of many factors, including psychiatric disorder, negative life events, psychological factors, alcohol and drug misuse, family history of suicide, physical illness, exposure to suicidal behaviour of others and access to methods of self-harm. In any individual case, multiple factors are usually involved. Suicide is often seen as a solution to a problem — this is usually intolerable distress, either physical or psychological, or both. The Table outlines the factors most commonly linked with an increased risk of suicide and Figure 1 demonstrates how some of these factors contribute to the suicide pathway.

Table: Risk factors most commonly linked to increased risk of suicide

Source: Sources: Hawton K & van Heeringen K. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. Wiley 2002:755[3]

; Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press 2007;276[6]

; McLean J, Maxwell M, Platt S et al. Risk and protective factors for suicide and suicidal behaviour: a literature review. 2008. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/Publications/2008/11/28141444/0 (accessed March 2019)[7]

; Simon RI. Assessing protective factors against suicide: questioning assumptions. Psychiatr Times 2011;28(8):35–35[8]

.

Figure 1: Suicide pathway model

Reproduced with permission from Centre For Suicide Research

Protective factors

Several factors are known to decrease the risk of suicide for any given individual, including:

- Social support[9]

; - Being in a loving relationship and/or having close family or friends[9]

; - Having religious or spiritual beliefs[7]

; - Being responsible for children[7]

; - Having a pet[8]

.

Psychological models describing the origins of suicidal behaviour

Joiner’s model for suicide

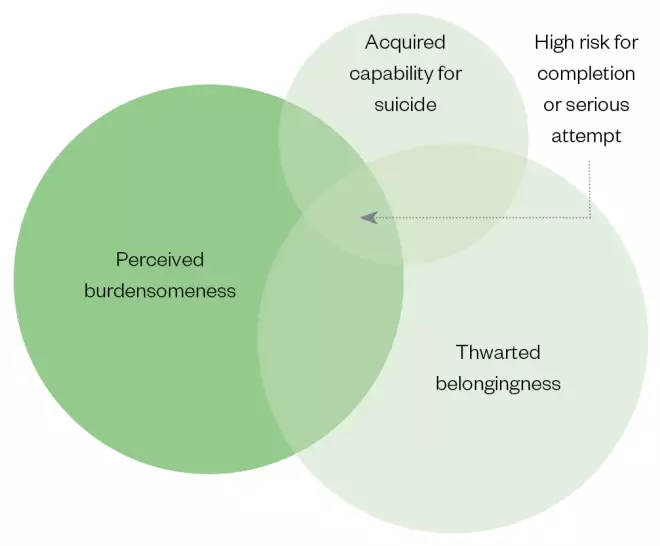

The interpersonal theory of suicide includes three components based on known risk factors of suicide: thwarted belongingness, perceived burdensomeness and acquired capability for suicide (see Figure 2)[6]

.

Figure 2: Joiner’s model for suicide

Thwarted belongingness describes the feeling that occurs when a need to belong is not met. This may be a result of rejection following repeated attempts to connect or environmental factors (for example, distance from family, mobility and access issues, financial constraints) leading to isolation. This often leads to a feeling of loneliness and occurs in the absence of reciprocal caring relationships[6]

.

Perceived burdensomeness is a belief system whereby an individual has the perception that they are a burden to those around them, usually perpetuated by beliefs about being flawed or being a liability to others[6]

.

Acquired capability for suicide occurs when individuals develop a higher tolerance for pain and/or violence and become at increased risk of suicide. This acquired capability may occur as a result of previous suicide attempts or through self-harm, through being exposed to maltreatment (either directly or indirectly), or by being exposed to the suicide of others, particularly friends and family[6]

.

The 3 I’s

Chiles & Strosahl propose that an individual experiencing suicidal ideation is likely to be experiencing three belief themes about their situation and their emotional or physical pain:

- It is Intolerable — the individual cannot bear the level of distress;

- Inescapable — the individual cannot see a way to escape from the pain;

- Interminable — there is no obvious end to this pain[10]

.

These belief themes lead to a sense of hopelessness and helplessness, which are strong predictors of suicide[11]

.

Determining the immediate level of risk

Training programmes and guidelines for front-line workers in improving access to psychological therapy services state that suicidal risk should be established by asking specific questions[12],[13]

that focus on five areas, and can be remembered using the acronym IPAPR:

- Intentions: is the individual having ideas about suicide?

- Plans: have they made any plans to end their life or have they thought about how they would do it?

- Actions: have they started taking steps towards carrying the plan out?

- Protective factors: what things have stopped them so far, what prevents them from progressing the first three areas?

- Resources: what resources do the individuals have that they can rely on to help?

How pharmacists can help

People with suicidal ideation are not forthcoming in mentioning the phenomenon, and yet advice for healthcare professionals and the public is to encourage conversation and sharing — ‘approach don’t avoid’. This can lead individuals to ask questions and expose their own fears — for example, how do I start? What should I say? How do I cover the most important information? How do I know how serious things are?.

The models and information described above can be applied strategically, which is examined in this article, including how to identify people who are potentially at risk of suicide (see Box 1).

Box 1: How to identify people at risk of suicide in the pharmacy setting

- Be vigilant to the prevalence of suicide;

- Look out for changes in the moods of your patients (e.g. are they particularly withdrawn?);

- Be aware of people not collecting routine medication, especially if they are on antidepressants;

- Be aware if someone appears to be stockpiling medication (e.g. asking for a lot of paracetamol).

If a person does share distressing ideas or you notice any of the warning signs, it is important to provide a safe space where they may feel comfortable to open up. Warm and sensitive questioning is essential. Pharmacists and pharmacy professionals should ensure they achieve three things:

- Provide the patient with an opportunity to talk;

- Ascertain the origin, extent and level of risk posed by their suicidal ideas and behaviours (see Box 2);

- Buy time and provide signposting and potential pathways to recovery (see useful resources).

Box 2: Consulting with a person who has suicidal ideas or behaviours

If, when asked, a patient reveals that they have been thinking about suicide or are feeling particularly low, encourage them to talk more, making sure to provide a safe environment for them to do so.

It should be possible to broach suicidal thoughts following general questions about mood and wellbeing (e.g. “It must be difficult to feel that way — is there ever a time when it feels so difficult that you’ve thought about death or even that you might be better off dead?”). Another approach is to reflect back to the patient your observations of their nonverbal communication (e.g. “You seem very down to me. Sometimes when people are very low in mood they have thoughts that life is not worth living: have you been troubled by thoughts like this?”).

The steps outlined below provide a framework for these difficult conversations.

1.

Ask about the origins of these thoughts.

Using Joiner’s model, look for signs and language that indicate that they feel like they do not belong anywhere, or that others see them as a burden. Ask if they have tried to harm themselves in the past.

Using the principles from the 3 I’s, ask them about the distress that they find themselves in:

- Can they bear it? (Intolerable)

- Do they see any light at the end of the tunnel? (Interminable)

- Is there any way out of their difficulties? What have they tried so far? (Inescapable)

Looking for signs of hopelessness and helplessness will provide an insight into the depth of the person’s suffering.

Useful questions include:

- Can you tell me a bit more about what you just said?

- How long have you been having these thoughts?

- When did they start? What has led to you thinking this way?

- Why do you think you are getting these thoughts?

- How do you see your future?

- Have you done anything about these thoughts and feelings?

- Have you had any of these thoughts before?

2.

Establish the nature, frequency and intensity of their suicidal thoughts and feelings

This can be achieved by following the IPAPR (intentions, plans, actions, protective factors and resources) pathway described above, particularly ascertaining intentions, plans and actions.

Useful questions include:

- Intent:

– How often do thoughts about suicide occur?

– How intense are these thoughts? How long do they last?

– Can you control these thoughts?

- Plans:

– Have you been thinking about how you might do this?

– Do you have a plan?

– When you have these thoughts, how strong are the impulses to act on them?

- Actions:

– Have you started to work out any details? What steps have you taken?

– How close are you to completing the plans?

Remember that the answers to the questions might provide some distressing information, but it is important to remain warm and empathic and try not to overreact. The UK charity Mind has produced a useful booklet for anyone experiencing suicidal feelings on how to cope[14]

.

3.

Signposting

The final stage involves signposting the individual to appropriate services and sources of support, and these will depend on the answers provided during the course of the conversation. For instance, if someone has already taken an overdose, asking them to stay with you and dialling 999 will be the immediate course of action. If the individual is at imminent risk, getting them to contact their doctor or mental health team would be appropriate. You could offer to do this for them or ask to stay with them while they make the call.

Exploring protective factors may be helpful and this could assist with finding out what resources they may already have.

Useful questions include:

- What immediate support do you have? Which friends or family might help you in a crisis? What things or people have stopped you acting on your thoughts of suicide?

- What has helped previously when your thoughts and feelings about suicide have been strong?

- What would be the disadvantages of acting on your suicidal thoughts?

- What would you miss about living? (Seasons, music, food, faith, comedy, hobbies, pets, smells, hot bath, exercise)

- Who would you miss? (Family, friends, colleagues)

- Who/what would miss you? (Children, grandchildren, friends, family, pets)

- What other ways of tackling your problems have you tried?

- What have you not yet tried?

Getting the individual to write down the answers to these questions in the form of a safety plan would be useful. Suggesting that the individual downloads an app — such as Stay Alive — would allow you and the individual to develop a safety plan, as well as ensure that the individual has a list of resources at the touch of a screen.

A list of helpful organisations and useful resources is included at the end of this article.

Looking after yourself

Engaging in these conversations is stressful and emotionally demanding, regardless of the subsequent outcome. It is important that this is acknowledged and that you ensure you support yourself. Using clinical supervision (if available) or talking to a trusted colleague is recommended routine practice.

Being kind to yourself and reminding yourself of the five steps to mental wellbeing (see Box 3) can help ensure that you maintain your own resilience and continue to provide much-needed support and services to your patients.

Box 3: Five steps to mental wellbeing

1.

Connect

Connect with friends, family, colleagues and neighbours, and spend time developing these relationships.

2.

Be active

Do exercise — this does not require gym membership and attendance; walking, cycling and playing active games all count.

3.

Keep learning

Deliberately learning something new and developing new skills improves wellbeing.

4.

Give to others

This includes small acts of kindness and larger contributions, such as volunteering.

5.

Be mindful

Being aware of your thoughts and feelings, your body and the world around you in the present moment is known as ‘mindfulness’. It can positively change the way you feel about life and how you approach challenges.

More information can be found on the NHS website.

Useful resources and organisations

References

[1] Office for National Statistics. Suicides in the UK. 2017. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2016registrations (accessed March 2019)

[2] Mental Health Foundation. Fundamental facts about mental health. 2016. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/publications/fundamental-facts-about-mental-health-2016 (accessed March 2019)

[3] Hawton K & van Heeringen K. The international handbook of suicide and attempted suicide. New Jersey: Wiley; 2002

[4] Center For Suicide Research University of Oxford. Assessment of suicide risk in people with depression: clinical guide. Available at: http://cebmh.warne.ox.ac.uk/csr/clinical_guide_assessing_suicide_risk.pdf (accessed March 2019)

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Quality standard: suicide prevention. In development [GID-QS10121]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/indevelopment/gid-qs10121 (accessed March 2019)

[6] Joiner T. Why people die by suicide. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 2007

[7] McLean J, Maxwell M, Platt S et al. Risk and protective factors for suicide and suicidal behaviour: a literature review. 2008. Available at: https://www.gov.scot/Publications/2008/11/28141444/0 (accessed March 2019)

[8] Simon RI. Assessing protective factors against suicide: questioning assumptions. Psychiatr Times 2011;28(8):35–35

[9] Suicide Prevention Resource Center; Rodgers P. Understanding risk and protective factors for suicide: a primer for preventing suicide. 2011. Available at: http://www.sprc.org/bpr/section-II/warning-signs-suicide-prevention (accessed March 2019)

[10] Chiles J & Strosahl K. Clinical manual for assessment and treatment of suicidal patients. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005

[11] Layard R & Clark D. Thrive: the power of psychological therapy. London: Penguin; 2014

[12] Richards D & Whyte M. Reach out. National Programme Student Materials to Support the Delivery of Training for Psychological Wellbeing Practitioners Delivering Low Intensity Interventions 3rd edition. 2011. Available at: www.rethink.org (accessed March 2019)

[13] Bennett-Levy J. Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010

[14] Mind. How to cope with suicidal feelings. 2016. Available at: https://www.mind.org.uk/media/4657603/how-to-cope-with-suicidal-feelings_2016.pdf (accessed March 2019)