Power and Syred / Science Photo Library

“If you’ve ever had chickenpox or seen your child suffer from chickenpox, then that’s a good place to start,” says 44-year-old Phil, who has lived with atopic dermatitis, also known as eczema, since he was a baby.

“You are told not to scratch, but have you ever tried not to scratch an itch? The itch intensifies, you’re thinking about it and the itch knows it. You can’t win so you scratch. You scratch until the itch stops,” he says. “With eczema sometimes the itch stops, sometimes it doesn’t.”

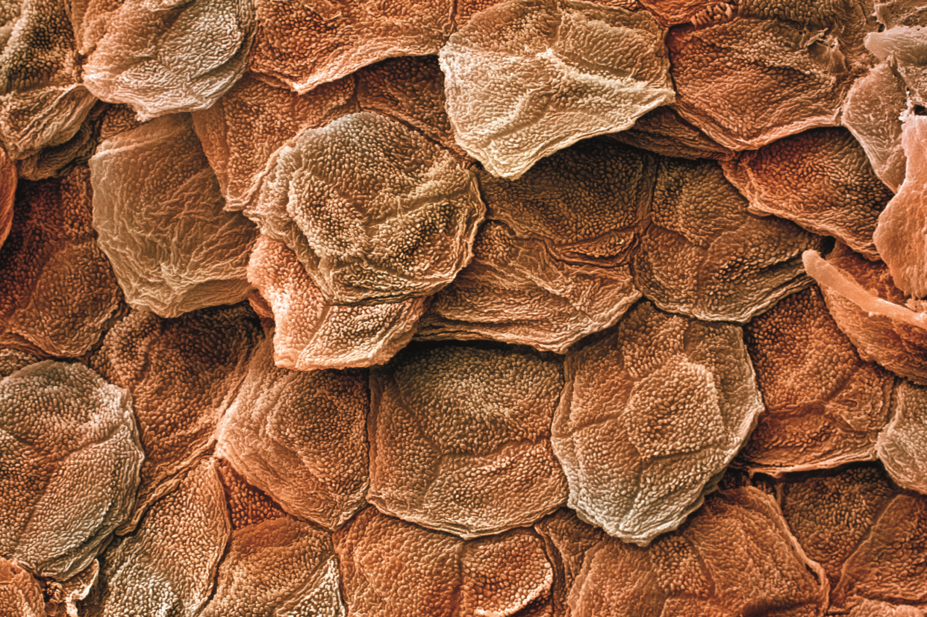

In atopic dermatitis, the itch comes first, both chronologically and in patients’ minds. Sometimes referred to as “the itch that rashes”, it is characterised by relapsing episodes of skin inflammation and intense itching, resulting in a rash and dry skin lesions that can bleed, ooze and become infected.

An often overlooked condition, for many patients atopic dermatitis is far from being “just eczema” but a disease that significantly impairs quality of life and prevents them from sleeping, working and general day-to-day functioning.

“I have the hands of an old outdoorsman; scarred, wrinkled and cracked,” says Phil. And the scars are not just physical. “I have always been uncomfortable meeting new people. I have to explain I’ve not been in an accident or a fight but I have a skin condition… and no, it’s not contagious.”

I have always been uncomfortable meeting new people. I have to explain I’ve not been in an accident or a fight but I have a skin condition… and no, it’s not contagious

It’s a difficult start and not good for your self-confidence, he adds.

But despite the impact that atopic dermatitis has on patients’ lives, there have been no major changes to the way the disease is treated in the past 15 years. Now, two medicines on the brink of entering the market could herald a new era in the treatment of atopic dermatitis.

The need for new treatments

Along with other atopic diseases, atopic dermatitis is affecting more and more people. In industrialised countries, the prevalence is thought to have increased by around three times since the 1950s, now affecting up to 30% of children and 10% of adults[1],

[2]

, with 20% of patients suffering from moderate-to-severe disease[3]

.

Mike Cork, a consultant dermatologist who heads up the Academic Unit of Dermatology Research at the University of Sheffield, says that he sees some of the worst cases in the country and regularly witnesses how devastating it can be.

“There’s a large number of children and adults with atopic dermatitis who are uncontrolled with every systemic drug that we have: ciclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate. They have 100% of their body covered, they have no life, they’re depressed, suicidal,” says Cork. “It’s an extremely distressing disease.”

There’s a large number of children and adults with atopic dermatitis who are uncontrolled with every systemic drug that we have: ciclosporin, methotrexate, azathioprine, mycophenolate. They have 100% of their body covered, they have no life, they’re depressed, suicidal

Research shows that patients with atopic dermatitis are three times more likely to have depression compared with controls[4]

, as well as a prevalence of suicidal ideation exceeding 15%[1]

.

Atopic dermatitis has two main pathological elements: impaired skin barrier function and immune dysfunction. Treatment approaches target the former, such as through regular use of emollients, and the latter with topical steroids or systemic immunosuppression. Antibiotics are sometimes needed to control infections, most frequently from Staphylococcus aureus. Phototherapy, using ultraviolet light, is also an option for some patients but it requires them to travel to specialised centres and has a high relapse rate.

But treatments applied to the skin are often used suboptimally, perhaps because they are not being applied enough or as frequently as they should. Treatment of atopic dermatitis is also limited by widespread steroid phobia, both on the part of patients and healthcare professionals.

Around 15 years ago, two topical calcineurin inhibitors — tacrolimus and pimecrolimus — were also licensed for the condition. In the United States, access to these treatments is hindered both by insurance companies’ reluctance to pay for them and a black box warning slapped on them by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005[5]

owing to a theoretical risk of lymphomas. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has also previously urged caution over their use[6],

[7]

. As a result, doctors and parents have been deterred from using an effective therapy by what some have argued are unwarranted safety concerns[5],

[8],

[9]

.

For patients with more severe disease whose condition is uncontrolled with topical treatments, there is one systemic immunosuppressant — ciclosporin — that can be used within licence for a year. Other than that, doctors often have to resort to borrowing systemic treatments from other areas of dermatology.

“In dermatology, clinicians have been very used to using medications off-label,” explains Raj Rout, UK dermatology medical lead at Sanofi, the French pharmaceutical company that is bringing dupilumab, one of the new therapies, to market. “They’re familiar with immunosuppressive drugs because they do use them in psoriasis where they have a licence, and in atopic dermatitis they do have some effect.”

Source: Courtesy of Raj Rout

Raj Rout, UK dermatology medical lead at Sanofi, says there are a few products in development that may change the way people approach the treatment of atopic dermatitis

However, all of these treatments can have significant side effects, such as infusion site reactions, neutropenia and an increased risk of infections. Amy Paller, director of the Skin Disease Research Center at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, says that concerns about side effects for any atopic dermatitis therapies are important, given how long patients have to remain on treatment.

“For many patients with this life-altering, uncomfortable disease, chronic use of medication is needed for control,” she says. “Without continuing medications — often daily, often strong steroids applied to the skin, and even oral medicines with some serious risks — patients are often not in control, and having miserable, miserable lives.”

She adds: “So there’s a need for more effective therapies and, certainly, safer treatments.”

There’s a need for more effective therapies and, certainly, safer treatments

Recent research has highlighted the key role of immunologic dysfunction in atopic dermatitis[1]

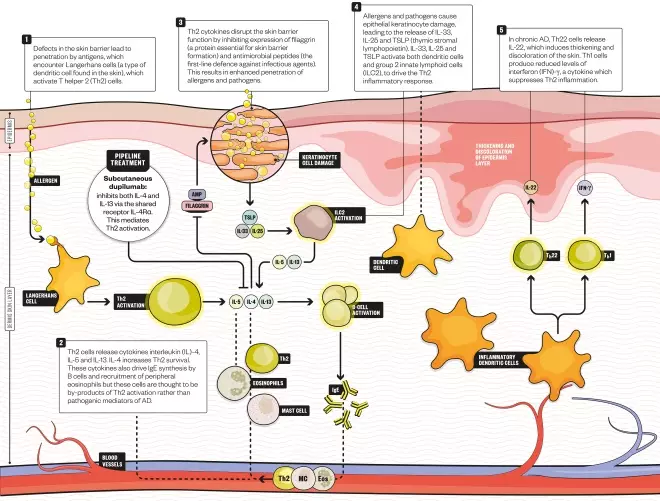

, which is shared with other atopic diseases, such as asthma. In particular, immune responses involving T helper 2 cells, known as the Th2 pathway, are central in both these conditions. And a greater understanding of the specific pathways and cytokines involved in driving inflammation in atopic dermatitis is now giving rise to therapies that act in a much more targeted manner. The aim is: better efficacy, fewer side effects.

Dupilumab: moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis

The arrival of the first monoclonal antibody for atopic dermatitis, dupilumab, marketed as Dupixent, is anticipated as a revolution for patients with the most severe form of the disease. Currently, these patients have nowhere to turn when their condition cannot be controlled with existing therapies.

The treatment has been in development for around seven or eight years by New York-based Regeneron, in part spurred by the chief scientific officer’s own father’s struggle with atopic dermatitis. Regeneron has now partnered with Sanofi to bring dupilumab to market.

How dupilumab works

Infographic by Alisdair MacDonald

Dupilumab targets the Th2 pathway that drives atopic dermatitis (AD).

Dupilumab works by inhibiting the interleukin (IL) 4-receptor alpha. This receptor interacts with two cytokines — IL-4 and IL-13 — that both play important roles in triggering Th2 immune responses in atopic dermatitis. It is given as a subcutaneous injection, expected to be given weekly or bi-weekly as a 300mg dose — these two dosage regimens performed similarly in clinical trials[10]

. Sanofi says it hopes that patients or carers will be able to administer the injections.

Atopic dermatitis is set to be dupilumab’s first licensed indication but the treatment is also in phase II trials for asthma and is being explored for use in nasal polyps and eosinophilic oesophagitis.

Results from phase III trials, known as SOLO 1 and 2, which were published in The New England Journal

of

Medicine in 2016[10]

, show that, after 16 weeks, nearly 40% of dupilumab-treated patients had an investigator global assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1, meaning their skin was clear or almost clear, and at least a two-point improvement on the IGA from baseline. This compared with around 10% of patients who received placebo. Patients had to have an IGA score of 3 or 4 (moderate or severe) before randomisation, and their median coverage was around 50% body surface area.

The results also showed that patient-reported scores for itch were significantly better for those receiving dupilumab compared with those receiving placebo from two weeks onwards. There were also significant improvements in quality of life for those in the dupilumab group, as well as improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depression, and a reduction in patient-reported symptoms and the impact of atopic dermatitis on sleep. The research did reveal, however, that injection-site reactions and conjunctivitis were more frequent in patients receiving dupilumab than in those receiving placebo.

The trials were carried out in North America, Europe, and Asia. Cork, who headed up the UK arm of the trials, says that itch improvement was one of the fastest and most noticeable improvements for patients who took dupilumab.

“[Dupilumab] reduces the inflammation so quickly that within a couple of weeks, patients’ scores might not have reduced at all but they say they’re cured,” Cork says. “They think it’s wonderful, because they can’t feel the itching anymore, which is the worst symptom.”

[Dupilumab] reduces the inflammation so quickly that within a couple of weeks, patients’ scores might not have reduced at all but they say they’re cured

Regeneron has also released results from a phase III trial comparing the use of dupilumab and topical corticosteroids with topical steroids alone in adult patients for up to 52 weeks, which also showed a favourable efficacy and safety profile[11]

. These are due to be presented at conferences in 2017 and were included in the drug’s FDA submission.

Sanofi says it anticipates a response from the FDA by the end of March 2017. It is also awaiting news on its submission to the EMA, which was accepted for review in December 2016.

Crisaborole: mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis

At the milder end of the atopic dermatitis spectrum, Pfizer, which is based in New York, secured FDA approval in December 2016 for its topical ointment crisaborole (Eucrisa), which was developed by California-based biopharmaceutical company Anacor.

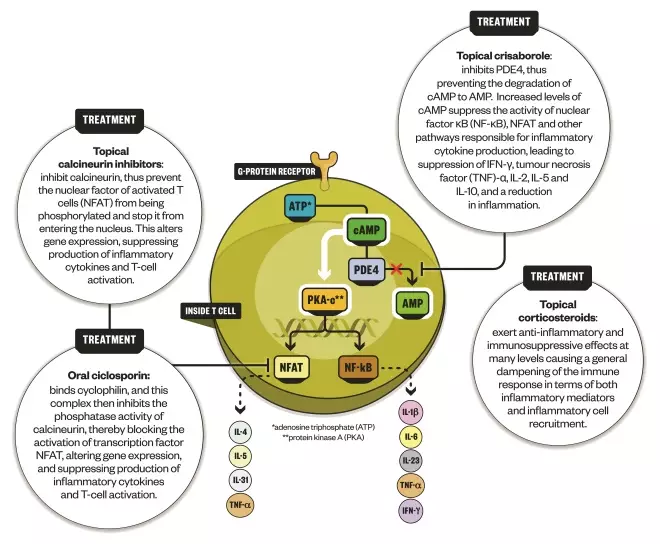

This treatment works by inhibiting the enzyme phosphodiesterase 4, which has long been known to have a role in atopic dermatitis. This enzyme impairs the activity of second messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), resulting in an increase of a whole number of cytokines involved in atopic dermatitis and other immune disorders. Crisaborole helps to reverse this process by increasing cAMP and decreasing cytokine production, thereby suppressing immune system activation.

How crisaborole works

Infographic by Alisdair MacDonald

Crisaborole inhibits the enzyme phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), which has long been known to have a role in atopic dermatitis

“It’s less targeted than dupilumab. But in comparison with steroids, both crisaborole and calcineurin inhibitors are more specific in that they just impact the skin’s immune abnormalities,” explains Paller, who was involved in trials of crisaborole. “Steroids have a lot of potential side effects, notably thinning of skin when applied to the skin chronically and in higher potencies.” She adds: “Crisaborole and calcineurin inhibitors are just doing the job that we want them to do when you’ve got an imbalanced, overly active skin immune system.”

In phase III trials conducted in the US, crisaborole was tested in patients with mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis aged two years and over[12]

. It was compared with vehicle alone over 28 days, at the end of which around 32% of crisaborole-treated patients met the primary endpoint of being clear or almost clear of atopic dermatitis (investigator static global assessment score [ISGA 0 or 1) with at least a two-point improvement in ISGA (scored from 0–4). This was significantly higher than the 18–25% of vehicle-treated patients reaching the primary endpoint. There were no serious adverse events and the main side effect was burning or stinging at the site of application.

Paller says that crisaborole should fill the niche that steroids and calcineurin inhibitors currently leave open resulting from fears — justified or otherwise — over side effects.

Source: Courtesy of Amy Paller

Amy Paller, director of the Skin Disease Research Center at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, says that concerns about side effects for any atopic dermatitis therapies are important, given how long patients have to remain on treatment

“I think that crisaborole will be a particularly welcome addition because of phobias about use, meaning that adherence to the prescribed regimen will be higher,” says Paller. “Because patients are so worried about the impact of topical steroids, and remain concerned about the [FDA’s] black box [warning on] calcineurin inhibitors, they’re welcoming something that’s new to the market that doesn’t have the black box, that doesn’t have the steroid side effects.”

I think that crisaborole will be a particularly welcome addition because of phobias about use, meaning that adherence to the prescribed regimen will be higher

This welcome could be particularly true for sensitive areas of the body, such as around the eye, where skin thinning and the risk of absorption through the skin are of special concern.

“I don’t think crisaborole is going to be more effective than topical steroids and the calcineurin inhibitors, but it is going to make many more people feel comfortable with using a prescription medication for atopic dermatitis, and that can make a big difference,” says Paller.

Not by drugs alone

Although clinicians are excited to get their hands on dupilumab and crisaborole, Tess McPherson, a consultant dermatologist at the Churchill Hospital in Oxford, says there are other factors in the care of atopic dermatitis that may ultimately be more important than developing new treatments. In particular, better, earlier and more aggressive treatment using existing therapies.

“These new targeted treatments are showing really exciting promise to treat established and difficult to manage atopic eczema,” says McPherson. “There seem to be fantastic outcomes for patients who have not been able to control their eczema with all the currently available treatments.” She adds that the effectiveness of targeted treatments is also helping us to understand disease processes better, in particular the importance of ongoing inflammation in atopic dermatitis.

But McPherson, who works predominantly with children and adolescents, says that, as more and more is known about the aetiology of the condition, there will also be a greater emphasis placed on preventing it from taking hold in the first place and stopping the so-called “atopic march” — the progression of atopic diseases that is thought to begin with atopic dermatitis and often ends in food allergies and asthma.

“It’s cheaper and hopefully, long-term, more effective to get the treatment right from the go, making sure that these children don’t have irritants on their skin and looking more into the environmental triggers that push children into atopic disease early on,” says McPherson. Environmental triggers are thought to include allergen and microbe exposure.

It’s cheaper and hopefully, long-term, more effective to get the treatment right from the go, making sure that these children don’t have irritants on their skin and looking more into the environmental triggers that push children into atopic disease early on

“These are areas of active research and I think they might turn out to be more important, McPherson adds.

Emma Wedgeworth, consultant dermatologist and a spokesperson for UK charity the British Skin Foundation, agrees. “Prevention is such an important area,” she says. “One in five children in the UK now have eczema and there are certainly, as yet, some environmental reasons for the huge increase over the last few decades.” She adds that there are currently studies looking to see whether certain skincare measures in infancy may affect the likelihood of a child developing atopic dermatitis. For example, a handful of early studies suggest that routine, full-body moisturisation from early in life could reduce the rate of atopic dermatitis in infants with a family history of atopic disease[13]

,[14]

.

Source: Courtesy of Emma Wedgeworth

Emma Wedgeworth, consultant dermatologist and a spokesperson for UK charity the British Skin Foundation, says there are currently studies looking to see whether certain skincare measures in infancy may affect the likelihood of a child developing atopic dermatitis

Hope for the future

After more than a decade in the wilderness, it is likely that the arrival of dupilumab and crisaborole is just the beginning of a large number of new therapies for atopic dermatitis.

“Eczema has really lagged behind psoriasis in terms of novel treatment options,” says Wedgeworth. “Hopefully as well as being good alternatives to help patients, the emergence of these products will also mark a new era in treatment for atopic dermatitis. In psoriasis, the introduction of biologics completely revolutionised our treatment pathways.”

Hopefully as well as being good alternatives to help patients, the emergence of these products will also mark a new era in treatment for atopic dermatitis

Rout from Sanofi agrees, saying that atopic dermatitis is now where psoriasis was around ten years ago. “Biologic therapies have come along and really changed the way that people view the treatment of psoriasis,” says Rout. “I think we are seeing a few products in development that may change the way that people approach the treatment of atopic dermatitis.”

Indeed, Reuters states that at least 25 pharmaceutical companies are now pursuing novel treatments for atopic dermatitis.

“It’s very exciting,” says Paller. “Dupilumab is really a breakthrough. It is the first targeted biologic that’s highly effective for atopic dermatitis. It won’t be the last — there are lots more in development — but it’s causing tremendous excitement.”

References

[1] Zane LT, Chanda S, Jarnagin K et al. Crisaborole and its potential role in treating atopic dermatitis: overview of early clinical studies. Immunotherapy 2016;8:853–866. doi: 10.2217/imt-2016-0023

[2] Bieber T. Atopic Dermatitis. NEJM 2008;358:1483–1494. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081

[3] Blakely K, Gooderham M & Papp K. Dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody for atopic dermatitis: a review of current literature. Skin Therapy Letter 2016;21. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/861428_1 (accessed February 2017)

[4] Dalgard FJ, Gieler U, Tomas-Aragones L et al. The psychological burden of skin diseases: a cross-sectional multicenter study among dermatological out-patients in 13 European countries. J Invest Dermatol 2015;135:984–991. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.530

[5] Bieber T, Cork M, Ellis C et al. Consensus statement on the safety profile of topical calcineurin inhibitors. Dermatology 2005;211:78–79. doi: 10.1159/000086431

[6] European Medicines Agency (2006). Protopic: EPAR – scientific conclusion. Available at: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Scientific_Conclusion/human/000374/WC500046828.pdf (accessed February 2017)

[7] Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb (2007). Topical tacrolimus and malignancies. Available at: http://www.lareb.nl/Signalen/kwb_2006_3_tacro (accessed February 2017)

[8] Segal AO, Ellis AK & Kim HL. CSACI position statement: safety of topical calcineurin inhibitors in the management of atopic dermatitis in children and adults. Allergy, Asthma Clin Immunol 2013;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-9-24

[9] Milone, A. Black box warnings have hampered eczema therapy. HemOnc Today 2008;23:1 Available at: http://www.healio.com/hematology-oncology/practice-management/news/print/hemonc-today/%7Bd914a3a4-d411-442e-a1ae-a47e01c41eec%7D/black-box-warnings-have-hampered-eczema-therapy (accessed February 2017)

[10] Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. NEJM 2016;375:2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020

[11] Regeneron (2016). Regeneron and Sanofi announce that dupilumab used with topical corticosteroids (TCS) was superior to treatment with TCS alone in long-term phase 3 trial in inadequately controlled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis patients. Available at: http://investor.regeneron.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=974316 (accessed February 2017)

[12] Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Derm 2016;75:494–503.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.046

[13] Horimukai K, Morita K, Narita M et al. Application of moisturizer to neonates prevents development of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:824–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.060

[14] Simpson EL, Chalmers JR, Hanifin JM et al. Emollient enhancement of the skin barrier from birth offers effective atopic dermatitis prevention. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014;134:818–823. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.005