MAG / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Erin Hallett was still a teenager when she saw the movie Kindergarten Cop. When it came to the famous “It’s not a tumour” line, voiced by Arnold Schwarzenegger, she remembers thinking, “I’m going to have a brain tumour”. Books could also be a trigger: on reading Deenie, a book by Judy Bloom in which the main character is diagnosed with scoliosis, Hallett developed backache.

If you Google any symptom long enough you come up with imminent death

But it was not until Hallett, now 40 years old and head of alumni relations at Imperial College London, reached her early 20s that her anxiety about her health became more of an issue. She attributes this in part to the rise of the internet. “If you Google any symptom long enough you come up with imminent death,” she says.

After Hallett’s father died of kidney disease when she was in her mid-30s, her anxieties escalated. “I couldn’t do my normal activities, I couldn’t get off the couch,” she remembers. Hallett kept turning up at her local walk-in clinic in her home country of Canada, where she was repeatedly told that there was nothing physically wrong with her. “I never believed them,” she says. Finally, a doctor at the clinic told her she needed to seek mental health support. It took another year and further worsening of her symptoms before Hallett presented at her GP, ready to take that advice.

Source: Courtesy of Erin Hallett

Erin Hallett hopes that by being honest about her condition, people will start to realise that health anxiety is an illness that you can manage like any other

Although she did not immediately accept the suggestion that she may have a mental health issue, Hallett believes it set her on the right track.

“I think we could help a lot of patients much earlier if they were recognised,” says Lisbeth Frostholm, a psychologist based at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Health anxiety is a relatively common problem. Although there are no official UK figures on the prevalence of health anxiety in the general population, an Australian study found that it affected almost 6% of people[1]

. And, Frostholm says: “If you do surveys in primary care or secondary care you find a higher prevalence rate.” This is because people with health anxiety tend to seek medical advice.

Peter Tyrer, a community psychiatrist at Imperial College London, led one such study in 2011, looking at people who visited five outpatient clinics — cardiology, respiratory medicine, neurological, endocrine and gastrointestinal — in London, Middlesex and North Nottinghamshire hospitals in the UK. He and his team found that almost 20% had significant health anxiety[2]

. “If you’re a cardiologist you’re seeing about 20 times more psychiatric patients than the average psychiatrist,” says Tyrer.

The result is that health anxiety is estimated to cost the NHS £420m in outpatient appointments alone, with further costs arising from unnecessary tests and investigations. “I insisted on every single blood test,” recalls Hallett.

“Health anxiety is probably one of the biggest conditions that we deal with and it’s definitely on the rise,” says Nicky Lidbetter, chief executive of Anxiety UK, a charity which supports and offers therapy to those living with anxiety and anxiety-based depression. She, like Hallett, blames ‘Dr Google’ for this. “If you put physical symptoms into Google very rarely does it come up with anxiety, it will always be something horrible,” she says.

Health anxiety is probably one of the biggest conditions that we deal with and it’s definitely on the rise

Of course, it is helpful if patients are well informed about their health, and the internet has a role to play in enabling this, but the problem comes when this tips in a pathological direction (see Panel 1).

Panel 1: What is health anxiety?

“Health anxiety is only a recent diagnosis,” says Peter Tyrer, a community psychiatrist at Imperial College London. It is beginning to replace the term ‘hypochondriasis’, which is still listed in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision, but has been removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM-5), published in 2013.

Source: Courtesy of Peter Tyrer

Peter Tyrer, a community psychiatrist at Imperial College London, led a randomised controlled trial into a modified cognitive behavioural therapy programme designed especially for health anxiety

Instead, the DSM-5 includes two new concepts — somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder. The differences between these conditions, and whether they are truly separate diagnoses, are still being contested. This is perhaps why many people prefer to use the broader term ‘health anxiety’, which encompasses both.

“We have different names and different ways of diagnosing health anxiety, so it is a confusing area,” acknowledges Lisbeth Frostholm, a psychologist based at Aarhus University in Denmark. While there is more work to be done in firming up the diagnosis, many people in the field agree with Joy McGuire, a cognitive behavioural therapist working in the NHS and the private sector, that hypochondriasis is a stigmatising term. “I don’t think anybody would have felt happy about having that label applied to them,” she says.

Health anxiety is characterised by excessive preoccupation with bodily symptoms (in the case of somatic symptom disorder) or a preoccupation with having or acquiring a serious medical condition (illness anxiety disorder). “The big thing that’s wrong is that people fail to pick up that the physical symptoms they’ve got stem from psychological causes,” says Tyrer.

Diagnosis anxiety

In 2013, Hallett received a formal diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder with a predisposition towards health anxiety. The development of health anxiety can be spontaneous, as in Hallett’s case, but Tyrer says that often the trigger is physical illness. He gives the example of someone who has been perfectly well and suddenly suffers a major health event, such as a heart attack. “The amount of psychological adjustment people have to make is enormous and they don’t receive much in the way of help for that,” he points out. They may become nervous about their health, interpreting innocuous chest pains or symptoms of anxiety, such as sweating or palpitations, as signs of another heart attack. Given this link, Tyrer says that health anxiety is more prevalent in older patients, who are more likely to have comorbid conditions.

You may be vulnerable to developing anxiety but certain triggers might decide whether you develop one kind of anxiety or another

Frostholm, who was one of the authors on a review of possible childhood and family risk factors for developing health anxiety, says: “You may be vulnerable to developing anxiety but certain triggers might decide whether you develop one kind of anxiety or another[3]

.” The review suggested that one such factor might be intergenerational transmission of certain beliefs:“If you have a parent who worries a lot you might learn this way of coping with symptoms.” Another factor seemed to be experience of illness — either their own or a carer’s — when young.

Source: Courtesy of Lisbeth Frostholm

Lisbeth Frostholm, a psychologist at Aarhus University, Denmark, has had success with a randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy, a variant of cognitive behavioural therapy, which was delivered to people with health anxiety in a group setting

On account of the focus on a physical cause for their symptoms, people with health anxiety are unlikely to be referred to psychiatrists. “Primary care physicians and secondary care outpatients deal with them more frequently than we ever see them in psychiatry,” says Tyrer. Joy McGuire, a cognitive behavioural therapist working in the NHS and the private sector, agrees. “One of the big problems with health anxiety is people not coming through for psychological work,” she says.

Getting the right help

Healthcare professionals who tend to see patients on a regular basis, such as GPs and pharmacists, often find it relatively easy to identify people who are more anxious about their health than usual. “Pharmacists are often local people and they know the local community,” Lidbetter points out.

“They might be coming back to the pharmacy constantly seeking information and reassurance,” says Thorrun Govind, a locum pharmacist based in Bolton. However, healthcare professionals need to know how to engage with this group and how to persuade them to seek psychological help. “I would expect that someone with health anxiety is going to feel very concerned about seeing a psychological therapist,” says McGuire. But there are effective interventions that can be recommended to try to break the cycle of consultations, reassurance and unnecessary investigations that fuels this type of anxiety. Neither the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) nor the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network have published specific guidelines on health anxiety. However, NICE does have guidance on the management of various anxiety disorders, including generalised anxiety disorder and obsessive compulsive disorder, which recommend initial self-help based on the principles of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), followed by CBT and then selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

Source: Courtesy of Thorrun Govind

Thorrun Govind, a locum pharmacist based in Bolton, says that giving people the chance to talk about their anxiety can help

Tyrer led a randomised controlled trial into a modified CBT programme, designed especially for health anxiety, which involved 444 patients (most of those potentially eligible for the study declined to participate)[4]

. Follow-up is ongoing, but after only six sessions of this “fairly simple” CBT, Tyrer and his team found that there was a significant improvement in the health anxiety scores of the treatment group compared with the control group which received a combination of clinical assessment, appropriate tests and reassurance. This effect was maintained at five years.

Reassurance is like taking an opioid drug because it works to begin with, and then it wears off and you become dependent

Tyrer believes these results are partly down to the fact that “the control group go on reinforcing their health anxiety with consultations and reassurance and unnecessary investigations”. In other words, just intervening in this cycle and asking people to think about their symptoms in a different way can make a big difference. “Reassurance is like taking an opioid drug because it works to begin with, and then it wears off and you become dependent,” says Tyrer.

Frostholm has had success with a randomised controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy, a variant of CBT, which was delivered to people with health anxiety in a group setting[5]

. “We found that this had a large effect in reducing the symptoms of health anxiety and led to a higher quality of life,” she says. With her team, she is now analysing the results of a trial in which the same intervention was delivered via the internet.

“There’s a number of things that we can do to help people notice what can have an impact on how you feel, physically and emotionally,” says McGuire, who did not take part in either study. She helps people with health anxiety to understand how their worries can lead to very real physical symptoms. “It’s about trying to get the message out about mind and body and how both connect with each other,” she says.

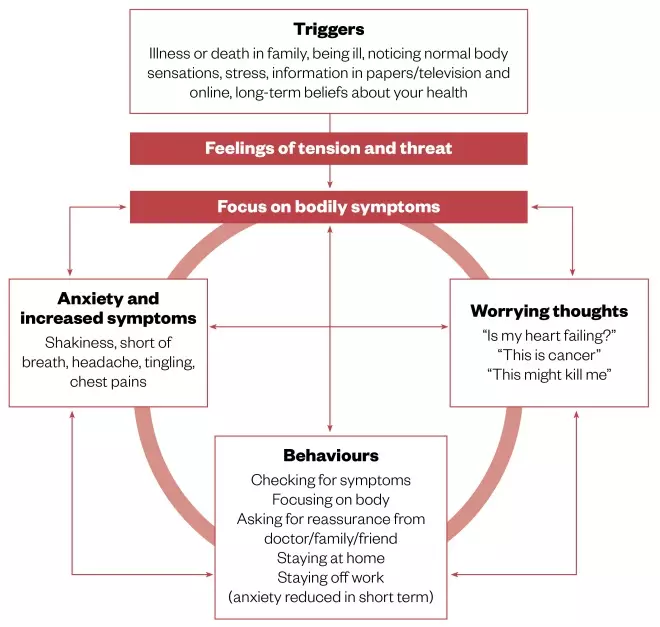

Figure: Health anxiety, a vicious cycle

Source: Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

People who worry excessively about their health may experience physical symptoms, which cause them to worry more, creating a vicious cycle of anxiety and increased symptoms

If we give people space first of all, just to talk about their experience, I think people really value that

However, before she even gets there, McGuire believes one of the most useful things she can do is provide a listening ear. She points out that the people who come to see her have often had frustrating experiences with doctors, in which they feel that they have not been given enough time to explore the issues they are concerned about or that their concerns have not been adequately addressed. “If we give people space first of all just to talk about their experience, I think people really value that,” she says. Govind has found that the same approach works in a pharmacy: “Sometimes it’s just about letting them say what they want to say.”

Drug treatments

Some people with health anxiety, including Hallett, can also benefit from pharmaceutical treatment. She was put on escitalopram, an SSRI. “I was lucky that the medication they put me on had no side effects — it was the right one right away,” says Hallett. That was fortuitous because both Tyrer and Frostholm have found that, in general, antidepressants and other psychiatric drugs are not particularly useful in people with health anxiety. “They’re quite sensitive to side effects,” Tyrer says of this patient group. “They read the patient information leaflet and that makes them worry,” Frostholm adds.

You can’t just take a pill and expect it to go away, you have to work at it all the time

For Hallett, a holistic approach has been important. “You can’t just take a pill and expect it to go away, you have to work at it all the time,” she says. CBT has been useful for her, as has acupuncture, and she also finds exercise helpful. Lidbetter says that exercise can be an excellent tool for dealing with the physical symptoms of anxiety: “If you’ve got a body that’s got high levels of adrenaline circulating around, then go and burn it off.”

To get an official diagnosis of health anxiety, an individual has to be assessed against the DSM-5 criteria by a psychiatrist. As a result, “most people have got an informal diagnosis”, says Lidbetter.In order to make it easier for people to get a sense of whether they may be suffering from health anxiety, the Anxiety UK website includes a DIY health anxiety diagnosis guide, which comprises six simple questions. “If you answer yes to them then that gives you an idea that maybe there’s an issue here,” says Lidbetter.

Source: Courtesy of Nicky Lidbetter

Nicky Lidbetter, chief executive of the charity Anxiety UK, says that exercise can be an excellent tool for dealing with the physical symptoms of anxiety

Having a diagnosis, whether formal or informal, can help people manage their condition by finding the right treatment, and alert healthcare professionals to the possibility that some of their symptoms may be caused by anxiety. When Hallett goes to the doctor now, she always mentions her health anxiety so that the message is, “I want you to take me seriously medically but I also need you to know that part of the reason I’m here is because I have health anxiety,” she says.

I want you to take me seriously medically but I also need you to know that part of the reason I’m here is because I have health anxiety

However, some people worry that if they reveal that they have health anxiety to a healthcare professional they will not be taken seriously, and that a diagnosis of a physical disease may be missed as a consequence. This is called ‘diagnostic overshadowing’ and, anecdotally at least, Lidbetter has heard accounts of people who “have been through the experience of not being believed once they’ve had this anxiety diagnosis” and have subsequently found out they have a physical condition.

Tyrer is less worried about diagnostic overshadowing. “The people in our study, they died earlier if they didn’t have [CBT] than if they did,” he points out. And a prospective study carried out in Norway looking at the risk of ischaemic heart disease in people with health anxiety found a doubling in the incidence of heart disease in the anxious cohort[6]

. “Monitoring your health and being very worried about it actually doesn’t work,” concludes Tyrer.

Doctor doctor

If ‘Dr Google’ is the underlying cause of a rise in health anxiety, the solution may lie in real-life doctors and allied professionals. The issue, Tyrer believes, is that outside of psychiatry, many healthcare professionals, including pharmacists, may not feel confident talking about mental health issues. He has spoken to his pharmacist about whether she could identify health anxiety: “She said yes, I’d have no problem picking that up, but what do I say to them?”

Tom Kallis, a pharmacist who is part of the Devon local pharmaceutical committee, agrees that there is a knowledge gap to bridge. “Having an understanding of patients who have been diagnosed with health anxiety would better equip pharmacists to respond appropriately,” he says (see Panel 2).

Having an understanding of patients who have been diagnosed with health anxiety would better equip pharmacists to respond appropriately

Govind believes that there is “more that pharmacists can do generally to be helping with mental health conditions”. Ben Merriman, who works as a community pharmacist in Barrow-in-Furness in Cumbria, believes this would be easier if pharmacists had access to patients’ full medical histories, including mental health diagnoses. “The sooner community pharmacy is seen as part of the NHS with a contribution to make to patients’ health and wellbeing, the better patient care will be,” he says.

Source: Courtesy of Ben Merriman

Ben Merriman, who works as a community pharmacist in Barrow-in-Furness, Cumbria, believes it would be easier for pharmacists to help people with health anxiety if they had access to patients’ full medical histories, including mental health diagnoses

However, Lidbetter sees this lack of access to records as a possible asset. She believes that people with health anxiety may be more likely to talk to a pharmacist than a GP because they “would feel able to have that kind of conversation knowing that it’s not going to appear on their medical record”.

Either way, opening up about mental health issues can be hard. Hallett has only recently started telling people, including at her workplace, about her anxiety. “I’ve just sort of come out about it and started talking about it, and that’s been a huge help,” she says. Hallett hopes that by being honest about her condition, people will start to realise that health anxiety is an illness that you can manage like any other, that “I’m 95% of the time fine, but 5% of the time I’m not OK.”

Panel 2: How pharmacists can help

Peter Tyrer, a community psychiatrist at Imperial College London, would advise pharmacists to take people with suspected health anxiety aside into their consulting rooms and have a conversation about whether excessive worry could be a trigger for their symptoms. He suggests pharmacists could even prompt patients to “look at the circumstances in which they occur — when you’re more worried, do you have these symptoms more?” Joy McGuire, a cognitive behavioural therapist working in the NHS and the private sector, goes a step further. “I think the ideal model for health anxiety would be for psychological therapists to supervise and train people who work in [front line] settings to be able to do it as part of their extended role,” she says.

Pharmacists can also signpost to other services, including their local improving access to psychological therapies (IATP) programme, an NHS England initiative from which people can self-refer for interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). Sue Pike, clinical and service manager for the Depression and Anxiety Service in Devon, says that pharmacists in her area are encouraged to put leaflets with information about IATP services into prescriptions for antidepressants or anxiolytics.

However, “probably the most useful approach is for pharmacists to openly chat when appropriate with their patients about mental health generally”, she says, adding that they should be confident about explaining the evidence for using CBT to treat anxiety, including health anxiety.

Resources that pharmacists might find useful, both to educate themselves and to recommend to their patients, include:

- Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust’s self-help guide for health anxiety

- The Helping Health Anxiety modules by the Centre for Clinical Interventions, North Metropolitan Health Services, Western Australia

- NHS Choices’s health anxiety page

- Anxiety UK

- No Panic

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists’s mental health advice

- The British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies

- NHS England’s ‘Improving access to psychological therapies’ programme

References

[1] Sunderland M, Newby JM & Andrews G. Health anxiety in Australia: prevalence, comorbidity, disability and service use. Br J Psychiatry 2013;202:56–61. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.103960

[2] Tyrer P, Cooper S, Crawford M et al. Prevalence of health anxiety problems in medical clinics. J Psychosom Res 2011;71:392–394. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2011.07.004

[3] Thorgaard MV, Frostholm L & Rask CU. Childhood and family factors in the development of health anxiety: a systematic review. Child Health Care 2017;47:198-238. doi: 10.1080/02739615.2017.1318390

[4] Tyrer P, Salkovskis P, Tyrer H et al. Cognitive-behaviour therapy for health anxiety in medical patients (CHAMP): a randomised controlled trial with outcomes to 5 years. Health Technology Assess 2017;21:1-58. doi: 10.3310/hta21500

[5] Eilenberg T, Kronstrand L, Fink P & Frostholm L. Acceptance and commitment group therapy for health anxiety — results from a pilot study. J Anxiety Disord 2013;27:461–468. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.06.001

[6] Berge LI, Skogen JC, Sulo G et al. Health anxiety and risk of ischaemic heart disease: a prospective cohort study linking the Hordaland Health Study (HUSK) with the Cardiovascular Diseases in Norway (CVDNOR) project. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012914. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012914