JL / The Pharmaceutical Journal

Chris Hannaway, a patient with a 14-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), used to take 500mg of metformin three times per day. Despite this, he was worried that his condition was so poorly managed that he would soon need insulin injections. Overweight, depressed, and with high blood pressure and high cholesterol, he struggled in particular with loose bowel motions and abdominal pains, both of which are known side effects of metformin. This made his job, which involved driving 12,000 miles per year, “a constant worry”.

“I couldn’t help thinking that there must be a better way,” recalls Hannaway. So, in 2012, when his doctor opened a routine appointment by asking him what he really wanted, Hannaway replied that he would like to stop taking the medicines and stop having T2DM. “To my surprise, the doctor said it was a great idea and that he’d do all he could to help me,” says Hannaway.

And that is what happened. Over the next seven months, Hannaway lost 16kg, stopped taking metformin — which ended his digestive symptoms in a few days — joined a gym and took up running.

“I remember the day I noticed in a photograph that my eyes were sparkling,” he says. Now, seven years later, his T2DM remains in remission without medicines.

Low-carbohydrate diets and deprescribing

Hannaway’s doctor, Southport GP David Unwin, described the appointment in a case review in the BMJ in 2015[1]

. He referenced emerging evidence that challenged mainstream medicine’s view that T2DM — which affects 4 million people in the UK and costs the country an estimated £9bn each year — is a progressive chronic disease requiring medicines for life.

Source: David Unwin

David Unwin, a GP in Southport, promotes the idea of a low-carbohydrate diet as a lifestyle change that helps people with type 2 diabetes mellitus take fewer drugs to manage their condition

“Like so many GPs, in 25 years of practice I had never seen any of my patients with T2DM actually getting better, no matter which drugs I used,” he said.

“Rather than push excess glucose in the bloodstream out of the body with medication, I had started to suggest to patients who were interested in a lifestyle option that they put less glucose in the body in the first place,” he explains.

Rather than push excess glucose in the bloodstream out of the body with medication, I had started to suggest to patients who were interested in a lifestyle option that they put less glucose in the body in the first place

Unwin’s 2014 paper in Practical Diabetes charted the impact of low-carbohydrate (low-carb) diets on 19 patients with T2DM or prediabetes in his practice over an eight-month period, concluding that “this approach brings rapid weight loss and improvement in HbA1C”[2]

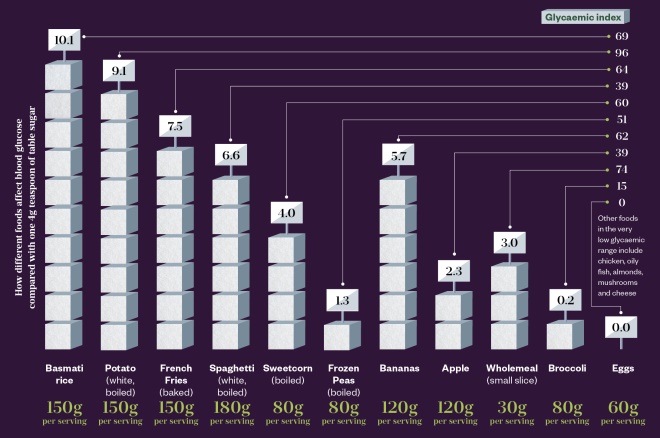

. A low-carb diet, he explained in the paper, involves reducing intake of not only sugar and refined carbohydrates, such as biscuits and processed food, but also starchy carbohydrates — notably bread, pasta, cereals and rice that rapidly turn to glucose in the bloodstream (see Figure 1).

He developed a series of infographics showing the impact of popular ‘healthy’ foods on blood glucose, such as wholemeal bread, potatoes and spaghetti compared with 4g teaspoons of sugar (see Figure 1). The resource was endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in March 2019.

Figure 1: Impact of popular ‘healthy’ foods on blood glucose

Source: Unwin D, endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

The glycaemic index (GI) ranks the carbohydrate levels of different foods to help predict their effect on blood sugar compared with pure glucose, which has a GI of 100. However, GI does not take account of the density of each carbohydrate in a portion of food — the glycaemic load, which is derived from the GI, is needed for this. The infographic shows the glycaemic load for a typical serving of various foods that are thought of as ‘healthy’, represented as the equivalent in teaspoons of sugar.

Hannaway achieved his ‘cure’ by cutting out bread. “I had been eating half a loaf or a baguette every day because I had been told it was the healthy thing to do,” he recalls. “I had have a sandwich before I went to bed to prevent [hypoglycaemia] while I slept.”

I had been eating half a loaf or a baguette every day because I had been told it was the healthy thing to do

Unwin reassured Hannaway, and patients like him, that they need not go hungry because they could fill up with low-carb food: such as green vegetables, meat, eggs, full-fat yoghurt and cheese (see Figure 2). Unwin cites eight systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials that found no association between saturated fat and disease. “It’s quite possible it’s beneficial to health,” says Unwin.

Figure 2: What does a low-carbohydrate diet look like?

There is a wide variety of nutritious and filling low-carbohydrate foods that people living with type 2 diabetes mellitus can eat

However, this is a contentious view; a 2018 review article on dietary fat and cardiometabolic health in the BMJ concluded that controversies remain about the long-term health effects of high-fat, low-carb diets, and research is needed to resolve these[3]

.

Unwin has continued to lead research in the UK and raise awareness via social media. In March 2016, he was the first GP to win NHS Innovator of the Year at the National NHS Leadership Recognition Awards, with recognition that his practice had “improved standards of diabetic care while spending over £40,000 less per year on drugs for diabetes”.

Today, partly through his influence, following a low-carb diet is a popular method of self-managing both obesity and T2DM. Numerous self-help guides and cookbooks provide support and, at time of publication, the website www.diabetes.co.uk has 412,505 people signed up to its low-carb programme. Tom Watson, the Labour Party’s deputy leader, is one of hundreds of people to go public on gaining remission from diabetes with a low-carb diet — in his case after losing 44kg.

Debate around the low-carb diet

But not everyone is on board the low-carb bandwagon. Jim Mann, professor of human nutrition and medicine at the University of Otago in New Zealand and a leading researcher in the field[4]

, warns that there is insufficient research to show long-term benefits of following a low-carb diet.

Source: Pav Kalsi

Pav Kalsi, senior clinical adviser at Diabetes UK, says a low-carbohydrate diet is just one evidence-based option that promotes weight loss

“A very wide range of carbohydrate intakes is acceptable for T2DM, and it depends on personal preference and the individual’s metabolic profile,” he said.

A very wide range of carbohydrate intakes is acceptable for T2DM, and it depends on personal preference and the individual’s metabolic profile

The charity Diabetes UK also takes a more measured stance, with the view that the solution to better diabetic control is weight loss, however it is achieved. “If you have T2DM and you’re overweight, losing weight can help improve your diabetes management and, if you lose a substantial amount, can even put your T2DM into remission,” says Pav Kalsi, senior clinical adviser at the charity. She says a low-carb diet “is just one evidence-based option that promotes weight loss along with low-calorie, low-fat and Mediterranean diets” (see Box).

Box: Low-carb versus other diets

A low-carb intervention is not the only dietary method of reversing type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Bariatric surgery brings about diabetes remission or improvement of blood glucose control and reduction of anti-diabetic medicines, according to 2017 research published in Frontiers in Endocrinology

[5]

.

The same year, the diabetes remission clinical trial (DiRECT), showed that a low-calorie intervention could put the disease into remission[6]

. Participants in DiRECT stopped all diabetic drugs on day one, under the supervision of GP staff, and then followed a low-calorie diet of soups and shakes over 90 days, with psychological support to return to a ‘normal’ diet. In the trial, half of the participants lost 15kg or more, achieving diabetes remission. An NHS England pilot study offering the liquid diet to 5,000 patients as the first treatment option following a new diagnosis of T2DM is under way.

Indeed, there is recognition that the right medicines are critical to managing the global epidemic of diabetes – preventing tissue damage, which can result in blindness, kidney failure and foot/leg ulcers for people whose blood glucose levels cannot be controlled by diet and exercise alone. “New innovations and new pathways to provide better management of diabetes are a priority,” says Kalsi.

However, a consensus report from the American Diabetes Association in April 2019 mentioned following a low-carb diet as an option for the first time, giving it a glowing recommendation[7]

. “Reducing overall carbohydrate intake for individuals with diabetes has demonstrated the most evidence for improving glycemia,” it says.

And there is also evidence showing the benefits of following a low-carb diet beyond reversing T2DM. Research published in Circulation in March 2019 shows the benefits of increasing circulation of ketones — the build-up of acids that occurs when the body burns fat because there is not enough glucose for energy — for people with congestive heart failure[8]

.

“We know ketones are good for the brain and now it seems they’re good for the heart too,” says David Ludwig, a doctor and nutrition researcher at Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Massachusetts. “But you don’t need an intravenous infusion. Carb restriction will do.” As well as metabolic syndrome, including heart disease and coronary artery disease, a low-carb diet may also prevent Alzheimer’s disease while improving overall fitness.

A job for pharmacists

If patients do decide to adopt a low-carb diet, many need intensive support and coaching to change what they have eaten for a lifetime, and to maintain this change. It is essential, Unwin says in the BMJ paper, “to give the patient the hope that he could have a better life” along with a guarantee of “continuity, seeing the same clinician on a regular basis who believed he could achieve his goal”.

Unwin has produced a video course for GPs but there is a growing view that advising on a low-carb diet is a job for pharmacists rather than family doctors.

Source: Jonathan Little

Jonathan Little, associate professor of health and exercise sciences at University of British Columbia, says pharmacists recognise the speed at which medicines need to be adjusted as people reduce their consumption of carbohydrates

“Many patients, and healthcare providers for that matter, may not appreciate or understand how to effectively manage medicines when dietary carbohydrates are reduced,” says Jonathan Little, associate professor of health and exercise sciences at University of British Columbia and lead researcher of an ongoing study into a pharmacist-led intervention in T2DM[9]

.

“Pharmacists do understand. They recognise the speed at which medicines need to be adjusted as people reduce their consumption of carbohydrates,” he adds.

Pharmacists recognise the speed at which medicines need to be adjusted as people reduce their consumption of carbohydrates

Campbell Murdoch, a GP in south-west England and medical officer for www.diabetes.co.uk takes the same view.

“Some people will greatly benefit from intensive coaching to support this lifestyle change and GPs may not have time or be unable to do this alone,” he says. “A team approach is needed. Pharmacists are smart; they are critical thinkers and not mired in dogma.”

Source: Campbell Murdoch

Campbell Murdoch, a GP in south-west England and medical officer for www.diabetes.co.uk, says pharmacists are critical thinkers and not mired in dogma

At least one pharmacist has already shown that such a scheme could work. Eoghan O’Brien, a community pharmacist in Portglenone, Northern Ireland, has unpublished data from a six-month course he ran from April to September 2018. The course was open to anyone collecting their diabetes medicines from his pharmacy and involved regular one-to-one, 20-minute chats and group coaching sessions on behavioural change, managing stress, nutrition and food labelling.

Of the ten people who accepted the offer, two achieved remission of T2DM: one stopped all medicines while the other, a newly diagnosed patient, was able to achieve remission without medicines. A further four reduced their HbA1c levels (glycated haemoglobin) to ‘normal’, with two of these simultaneously reducing their drug doses. At the same time, three out of the ten who did not “engage fully with the course” had no change or increased their medicines over the six months.

Source: Eoghan O’Brien

Eoghan O’Brien, a community pharmacist in Portglenone, Northern Ireland, stresses the importance of goal setting when starting a lifestyle change

“Goal-setting at the start is important,” says O’Brien. A 75-year-old man who enlisted because he hates needles and, like Hannaway, wanted to prevent “the next step insulin”, reduced his HbA1c level and shed 8kg while stopping empagliflozin and reducing gliclazide by 30mg.

A similar approach could soon begin in England. All seven CCGs in north-east London recently provided training in health coaching (two full days plus four evening sessions) to 180 of their 500 pharmacists. “The plan is for them to offer a low-carb lifestyle intervention to people with T2DM,” says Hemant Patel, secretary of North East London Local Pharmaceutical Committee. “The service has been agreed in principle, but will need to be funded in order to be sustainable and accountable,” he adds.

“This project will be quite different from telling people what to do or being judgemental,” explains Patel. “We’re training [pharmacists] to understand the mindset that leads to patients with T2DM overeating refined carbohydrates.”

The pharmacists can then use powerful psychological health coaching tools to work with patients to create a vision of sustainable lifestyle change, he says.

Finding food that stabilises blood sugar using a continuous glucose monitor can prolong good-quality life

Some pharmacists are providing private services to help people living with T2DM adopt a low-carb diet. Graham Phillips, superintendent pharmacist at Manor Pharmacy Group in Hertfordshire, offers a private eight-week service with continuous glucose monitoring, expert analysis of blood sugar readings and one-to-one coaching. This builds on recent evidence from Israel[10]

and the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota[11]

, showing that the glycaemic response to food is highly individual, driven mainly by the gut microbiome but with an additional genetic element that means there are no dietary rules that apply to everyone. “Food that causes blood sugar spikes in one person is benign in another,” explains Phillips. “Finding food that stabilises blood sugar using a [continuous glucose monitor (CGM)] can prolong good-quality life,” he adds.

Setting up a pharmacy service

When setting up a pharmacy service, an accurate HbA1c analyser is essential, O’Brien says; an ideal device would give a result in less than five minutes and show patients how the choices they are making affect blood sugar control, all while measuring overall progress. A 63-year-old insulin-dependent woman on O’Brien’s course who discovered that oats and potatoes spiked her blood glucose lost 4kg over six months and reduced her HbA1c by swapping porridge for eggs while cutting back on potatoes and oatcakes.

For O’Brien’s second course later in 2019, participants will be given CGMs that provide immediate feedback on the impact of meals on their blood sugar. The usefulness of these digital aids was demonstrated in a 2018 study in Diabetes Therapy that is widely seen as finally providing proof that a low-carb diet is a viable lifestyle intervention[12]

.

The study, carried out by Indiana University and the US-based diet-coaching firm Virta Health, found that by following a low-carb diet, 60% of 262 obese patients with long-term T2DM lost a minimum of 12% of their body weight — an average of 13.6kg — over six months. Each participant received regular remote support with daily texts and telephone calls from a specially trained life coach, along with use of a CGM. Data from the glucose monitor were remotely accessible to the participant, coach and a doctor who was supervising the reduction of diabetes drugs. The result was sustained after a year. “Our approach is changing the diabetes care model,” says Sarah Hallberg, medical director at Virta and principal investigator in the study.

Financial viability

The crux of the matter will be whether the low-carb intervention — as described by the Virta study — is financially viable for community pharmacies. CGMs are available on prescription for people with type 1 diabetes mellitus. But, as Keith Vaz, chair of the All Party Parliamentary Group for Diabetes, stated in February 2019 at a meeting in the House of Commons, they “will never be prescribed for T2DM because it would bankrupt the country”.

That observation misses the point, says O’Brien. “People with T2DM only need to use CGMs in the short term — a few weeks — until they have worked out which food can be safely consumed without affecting blood glucose and insulin.”

People with T2DM only need to use CGMs in the short term — a few weeks — until they have worked out which food can be safely consumed without affecting blood glucose and insulin

O’Brien is currently applying for lottery funding to pay overheads, including the purchase of CGMs for his next course later in 2019. He is also applying to the local health board for a fee of £300 per person for administration costs, including an extra assistant to cover while he is working as a coach. Against that, the pharmacy has already achieved an annual saving of more than £1,100 on its diabetic drugs bill by supporting just seven patients to switch to the lifestyle intervention.

The same fee-paying system is not available in England. “I would love to offer a similar service on the NHS,” says Phillips.

Although there could be a loss of dispensing income, this could help with the development of a more clinical role for pharmacy, says Patel. “It’s a matter of repositioning pharmacy as a community asset. That’s a way bigger development than the loss of prescriptions,” he says.

References

[1] Unwin D & Tobin S. A patient request for some “deprescribing”. BMJ 2015;351:h4023. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4023

[2] Unwin D & Unwin J. Low carbohydrate diet to achieve weight loss and improve HbA1c in type 2 diabetes and preâ€diabetes: experience from one general practice. Practical Diabetes 2014;31(2):76–79. doi: 10.1002/pdi.1835

[3] Forouhi NG, Krauss RM, Taubes G et al. Dietary fat and cardiometabolic health: evidence, controversies, and consensus for guidance. BMJ 2018;361:k2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k2139

[4] Reynolds A, Mann J, Cummings J et al. Carbohydrate quality and human health: a series of systematic reviews and meta-analyses.Lancet 2019;393(10170):434–445. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31809-9

[5] Kassem MAM, Durda MA, Stoicea N et al. The impact of bariatric surgery on type 2 diabetes mellitus and the management of hypoglycemic events. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2017;8:37. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2017.

[6] Lean MEJ, Leslie WS, Barnes AC et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018;391(10120):541–551. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33102-1

[7] Evert, AB, Dennison M, Gardner CDet al. Nutrition therapy for adults with diabetes or prediabetes: a consensus report. Diabetes Care 2019;42(5):731–754. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0014

[8] Nielsen R, Møller N, Gormsen LC et al. Cardiovascular effects of treatment with the ketone body 3-hydroxybutyrate in chronic heart failure patients. Circulation 2019;139(18):2129–2141. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036459

[9] Little J. Pharmacist-led therapeutic nutritional intervention in type 2 diabetes. 2018. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03181165 (accessed May 2019)

[10] Zeevi D, Korem T, Zmora N et al. Personalized nutrition by prediction of glycemic responses. Cell 2015:163(5):1079–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.001

[11] Mendes-Soares H, Raveh-Sadka T, Azulay S et al. Assessment of a personalized approach to predicting postprandial glycemic responses to food among individuals without diabetes. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2(2):e188102. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.8102

[12] Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Williams PT et al. Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study. Diabetes Ther 2018;9(2):583–612. doi: 10.1007/s13300-018-0373-9

You may also be interested in

Manufacturer confirms discontinuation of type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment Victoza

Pharmacy-led national diabetes screening service could save NHS £50m a year, says CCA