Mclean/Shutterstock.com

At the age of 21 years, chronic pain was destroying Antony Chuter’s life: he had lost his job, his home and his partner.

Almost 30 years later, Chuter — now chair of Pain UK, an alliance of charities providing support for people living with pain — says many others are still going through the same experience. “Chronic pain affects the whole of your life, and it affects the lives of people around you in a very profound way.

“Pain is so draining. Trying to switch off the panic and anxiety is really hard,” he adds.

Chronic pain — defined as pain that has persisted for more than three months — is thought to affect around 28 million people in the UK and, according to the Royal College of General Practitioners, is a presenting condition in around 22% of primary care consultations[1]

.

Although most people living with back pain, arthritis or chronic headaches can be managed in general practice with conservative drug treatment and lifestyle advice, more complex patients will require the support of specialist services. These services are designed to provide a more holistic treatment plan, ensuring that patients receive help to cope with their pain using non-drug alternatives, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and psychological interventions.

Non-drug management

The evidence shows that such holistic care can make a positive difference to patient’s lives[2]

. However, data obtained by The Pharmaceutical Journal under the Freedom of Information (FOI) Act reveal that waiting times for specialist services vary hugely across Great Britain, and that some patients wait years to access the treatment they so urgently need. The International Association for the Study of Pain recommends an eight-week maximum wait for a non-urgent outpatient appointment, but the figures from secondary care specialist pain management services show that patients often wait much longer[3]

.

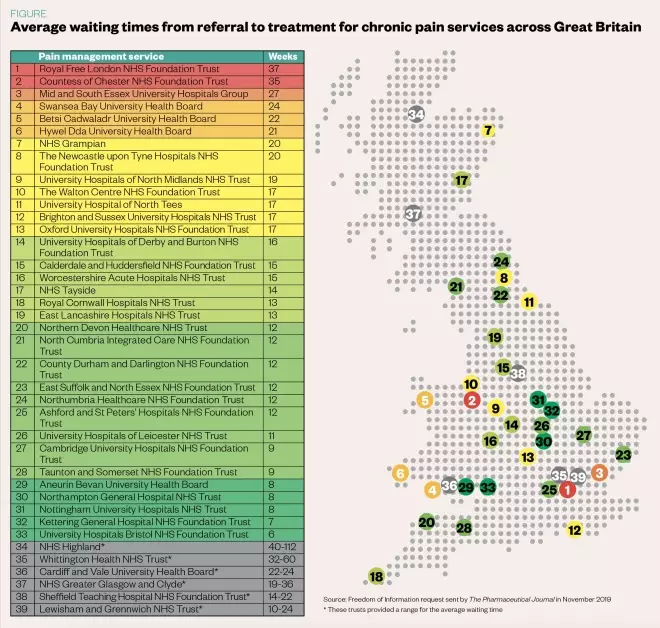

The average waiting time from GP referral to treatment at 39 services in Great Britain ranges from 6 to 112 weeks, with 87% of providers reporting an average wait of longer than 8 weeks (see Figure). Waiting times in Wales are particularly long, with four out of five providers that responded reporting average waiting times of over 20 weeks.

The longer waiting times in Wales could be a result of less stringent NHS targets. Patients in England and Scotland have a right to start consultant-led treatment within 18 weeks of GP referral whereas in Wales, 95% of patients should be seen within 26 weeks and all patients within 36 weeks.

Figure: Average waiting times from referral to treatment for chronic pain services across Great Britain

Source: Freedom of Information request sent by The Pharmaceutical Journal in November 2019

However, some patients with chronic pain wait more than two years between referral and treatment, with NHS Highland specifying a range of 40–112 weeks, which a spokesperson put down to “increased referrals to the pain management service”.

We apologise to all patients that have been let down by long waiting times

The Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, which reported an average waiting time of 37 weeks, says that it is taking action to reduce this through additional staff recruitment.

“In addition, local commissioners are developing services in the community to manage chronic pain,” a spokesperson for the trust adds.

“This will mean that only patients requiring treatment in a hospital setting are referred to the Royal Free London in future and waiting times will decrease.”

The Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, where patients wait an average of 35 weeks for treatment, is also recruiting to try to meet demand. Susan Gilby, chief executive at the trust, explains that waiting times are much longer than she would like. “We are actively recruiting for a chronic pain specialist to help with this and we are also seeking solutions internally to increase our capacity moving forwards,” she says.

“We apologise to all patients that have been let down by long waiting times,” she adds.

Losing faith in the profession

“My experience of seeing patients in the pain clinic is that it has been a long, long time before they actually get there,” says Lorraine de Gray, a pain consultant at Queen Elizabeth Hospital King’s Lynn NHS Foundation Trust in Norfolk and vice dean of the Faculty of Pain Medicine (FPM) at the Royal College of Anaesthetists.

“And a lot of them have lost faith in the medical profession by the time they do — particularly the ones who still don’t understand why they have pain.”

Not only do patients lose faith in the medical profession during these long waiting times for specialist care, but their health can suffer too. Research shows that patients who wait longer than six months for treatment experience deterioration in health-related quality of life and psychological wellbeing[4]

. “Patients can deteriorate over that time quite dramatically,” explains Emma Davies, advanced pharmacy practitioner in pain management at Swansea Bay University Health Board in Wales, who delivers training and education in pain management.

A lot of people with chronic pain will have problems with work and with life in general

“It is harder for pain services to support more debilitated or severely affected people and their options may be more limited.” This, she says, has a serious impact on how long rehabilitation can take, and how effective it is.

Chronic pain often leads to fear, anxiety, and avoidance behaviours, where the person stops engaging in activities that they associate with pain. Over time, this means people abandon the hobbies they enjoy, and lose the escapism this would otherwise bring. This, in turn, can lead them to focus on their pain even more.

It is not just the psychological and physical aspects of chronic pain that people need help with: “A lot of these people, by the time they get to you, will have problems with work and with life in general, so that’s where an occupational therapist can be very useful in terms of … helping them to stay in work,” says de Gray.

However, accepting that chronic pain often cannot be treated with a pill is not easy for some.

“Shifting patients from looking for something that is going to get rid of the pain to accepting that they are stuck with the pain, but there is still something they can do is difficult,” explains Amanda Williams, clinical psychologist and reader in clinical health psychology at UCL.

Cultural shift

The problem is two-fold: there is a culture of a pill for all ills in this country, and rehabilitation takes much more effort, says Williams.

Given the choice of doing exercise or taking paracetamol, a lot of people would take paracetamol

“Given the choice of doing an hour of exercise or taking a paracetamol, a large number of people would take a paracetamol,” she argues. “It often seems we blame patients for things that are human characteristics. We assume that somehow they are weak if they don’t want to go to the gym every day, or take a brisk walk, but lots of healthy people don’t.”

For a lot of people, being prescribed a strong analgesic validates their pain. “If you say to a neighbour or to the people who are reviewing your welfare payments that the pain is so bad that you’re prescribed 100mg morphine, then people are going to take it more seriously than if you say that you don’t take any painkillers for it,” explains Williams.

Yet there is little high-quality evidence to support the use of strong analgesics, such as opioids, to manage chronic pain. Many studies of opioids for chronic pain have low-compliance rates, with patients discontinuing treatment owing to adverse effects or with insufficient pain relief[5]

. There are also only limited data that provide evidence to support use of opioids for longer than six months

[5].

“I certainly think that GPs are grappling with the unavailability of non-drug provision, which is still very patchy across the country; in some areas it will exist, but they are unaware of it or sceptical so do not refer [patients],” says Williams.

“It has become more of an issue with pressure to reduce opioid prescriptions, and GPs feeling they have little or nothing to offer in its place.”

Chuter agrees: “GPs have very little to offer patients. Their hands are tied. All they can do is refer to pain management, physiotherapy and talking therapies.

“Other than that, they medicate with antidepressants and pain medication, and the problem with pain medication is that they step it up and step it up and step it up because they just don’t know what else to do,” he adds.

Multidisciplinary working

Despite the long waits, most pain clinics have come a long way from what used to be an anaesthetist-only, interventionist model. The FOI request from The Pharmaceutical Journal shows that 67% of 34 services that responded to this question in England, and 80% of 5 services each in Wales and Scotland, have multidisciplinary chronic pain teams, including consultants, physiotherapists and psychologists as a minimum, with most of the rest having access to these disciplines.

This is an improvement from the first National Pain Audit report in 2012, which found that 40% of clinics in England and 60% of those in Wales were sufficiently staffed for multidisciplinary working, although a second audit in 2013 put this figure at 67% for England[6]

,[7]

.

A quarter (25%) of 44 services that responded in Great Britain had a pharmacist on the multidisciplinary team, with a further 16% specifying that the team had access to a pharmacist.

The FOI request also shows that 80% of services offer non-pharmacological treatments, such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and psychological therapy.

De Gray believes that the FPM core standards for pain management, published in 2015, have helped clinics to expand their offerings[8]

. “Following engagement with the Care Quality Commission (CQC), key standards from ‘Core standards for pain management services in the UK’ are being incorporated across all core services standards used by the CQC when undertaking visits,” she says.

“This has helped us, as clinicians, to source funding to meet these standards.”

The standards for secondary care pain management services specify that the multidisciplinary team must include medical consultants trained in chronic or acute pain medicine, nurses, physiotherapists, clinical psychologists and occupational therapists, with access to dedicated pharmacist input.

“Pharmacists may support other members of multidisciplinary pain management services by undertaking regular medication reviews to assess the safety, effectiveness and tolerability of medicines prescribed for pain relief,” the standards say.

They also specify that physiotherapy and psychological therapies — such as cognitive-behavioural therapy, motivational interviewing and acceptance and commitment therapy — should be made available to patients at all stages of pain management, and that self-management strategies should be emphasised and reinforced.

Solutions

If chronic pain could be managed effectively, it would help to prevent multiple GP and hospital visits, high analgesic use, poor quality of life and unemployment owing to ill health[9]

.

Jens Foell, a GP in North Wales with an interest in pain medicine and education, believes that a new model is needed.

“In each of my consultation days I have more than five difficult consultations about chronic pain,” he says. “From such situations the urge to refer and defer emerges. Sometimes from the practitioner, sometimes from the patient — sometimes both parties do not want to face the here-and-now as a place of common departure, and they defer to the future and dissolve the responsibility to the waiting list.”

The system is failing patients; it’s failing GPs. And pain consultants in the hospitals probably feel that everything is being thrown at them

Foell argues that all frontline and community staff, including GPs, physiotherapists, nurses, pharmacists and paramedics, should be trained to understand the complexity of chronic pain, as well as how to be “emotionally available” for people in distress. “It is more about enabling all practitioners to deliver compassionate care to the ones who suffer than medicalising it to a service model that can never live up to the expectations but keeps on asking for more and more resources to do something ineffective.”

Chuter would also like to see more specialised services available in the community so that they are easier for patients to access: “The system is failing patients; it’s failing GPs. And pain consultants in the hospitals probably feel that everything is being thrown at them.”

He asks: “Should pain physiotherapists come out of hospitals and be in local sports centres so people who have been on pain management programmes can drop in and receive extra support? Should occupational therapists be in people’s homes seeing what adaptations they need and working with them to get them back into employment?

“People are fed into these pain management programmes, which have a positive impact on people’s lives, but sustaining that is the problem. Nobody goes back to see how they are doing two or four years later,” he explains. “In the long term, these people need more support.”

Special report: Non-drug interventions

This article is part of a special report on the increasing use of non-pharmacological treatments in the health service.

Click here to find out more

References

[1] Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM et al. BMJ Open 2016;6(6):e010364. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364

[2] The British Pain Society. 2013. Available at https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/pmp2013_main_FINAL_v6.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[3] International Association for the Study of Pain. 2011. Available at: http://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/NavigationMenu/EducationalResources/IASP_Wait_Times.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[4] Lynch ME, Campbell F, Clark AJ et al. Pain 2008;136(12):97–116. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.06.018

[5] British Medical Association. 2019. Available at: https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/public-and-population-health/analgesics-use (accessed February 2020)

[6] The British Pain Society. 2012. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/members_articles_npa_2012_1.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[7] The British Pain Society. 2013. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/members_articles_npa_2013_safety_outcomes.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[8] Faculty of Pain Management of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. 2015. Available at: https://fpm.ac.uk/sites/fpm/files/documents/2019-07/Core%20Standards%20for%20Pain%20Management%20Services.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[9] Chronic Pain Policy Coalition. 2015. Available at: https://www.policyconnect.org.uk/sites/site_pc/files/report/668/fieldreportdownload/cppcthehiddensufferingofchronicpainnov2015.pdf (accessed February 2020)

You may also be interested in

Research proves that antibiotics are ineffective in chronic lower back pain with Modic change

Antidepressants mostly ineffective at reducing pain, finds meta-analysis