DR. MICHAEL SOUSSAN/ISM/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic, progressive neurodegenerative condition resulting from the loss of the dopamine-containing cells of the substantia nigra, and its prevalence increases with age[1]

. Using primary care data from 2015, a Parkinson’s UK report of the Clinical Practice Research Datalink found that the prevalence of PD is 4–5 per 100,000 people who are aged 30–39 years, compared with 1,696 per 100,000 people who are aged 80–84 years[2]

. Prevalence rates almost double at each five-year interval between the ages of 50 and 69 years for both men and women. The lifetime risk of being diagnosed with PD is 2.7% — equating to 1 in every 37 people being diagnosed at some point in their lifetime. Owing to population growth and an increasing ageing population, the estimated prevalence of PD is expected to increase by 23.2% by 2025[2]

.

Aetiology

The cause of PD still remains unknown but it has long been hypothesised that exposure to environmental risk factors may be one cause, along with an inherited susceptibility. The majority of cases are thought to arise sporadically, although up to 20% of people with PD also have a first-degree relative with PD. It is theorised that 24 genetic loci have a clinically significant association with PD risk[3],[4],[5]

. Consequently, it is currently believed that parkinsonian syndromes are a blanket term for several neurodegenerative diseases. Studies show that age of onset is important and that onset after 50 years of age is less likely to be genetically influenced[6]

. The development of PD is negatively associated with cigarette smoking, coffee and alcohol consumption, while physical activity has been shown to be beneficial in relieving symptoms in those undertaking the PD Warrior programme[7]

.

Pathophysiology and presenting features

Classic presenting features of PD include motor symptoms, such as bradykinesia, rigidity, rest tremor and postural instability. However, non-motor symptoms, such as depression, cognitive impairment, pain and autonomic disturbances, are also often present and they can severely affect a patient’s quality of life[8]

. There are several information sheets available for patients that cover the management of multiple common types of pain in PD[9]

.

The motor symptoms are largely caused by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra compacta, which ultimately reduces dopaminergic input to the striatum and other brain regions[10]

. Compensatory mechanisms in the brain are so effective that the clinical symptoms of PD may only develop when around 80% of dopaminergic neurons have degenerated[1]

. By contrast, the Braak theory of PD suggests that the disease process starts in the olfactory bulb and lower part of the medulla, and it is not until stage 3 that the substantia nigra becomes involved in the process[11]

. There is also direct evidence of Parkinson pathology being spread from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the brain in rodents[12]

. There are therapeutic implications of gut involvement; it is known that swallowing and the stomach are the two main problems of PD therapy and lead to the use of non-oral therapies.

Historically, the three pathological hallmarks of PD were the presence of Lewy bodies, neuronal death in the pars compacta of the substantia nigra and the loss of pigmented neurons in pigmented brainstem nuclei. Lewy bodies are protein aggregates of abnormal alpha-synuclein and were believed to be pathogenic in PD, leading to cell death. The number of Lewy bodies increases with age, which correlates with the increasing incidence of PD in older people. However, it is important to note that the presence of Lewy bodies can be asymptomatic and not associated with PD[3]

, as their presence can also be found in other neurodegenerative diseases (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, multisystem atrophy and Lewy body dementia)[3]

.

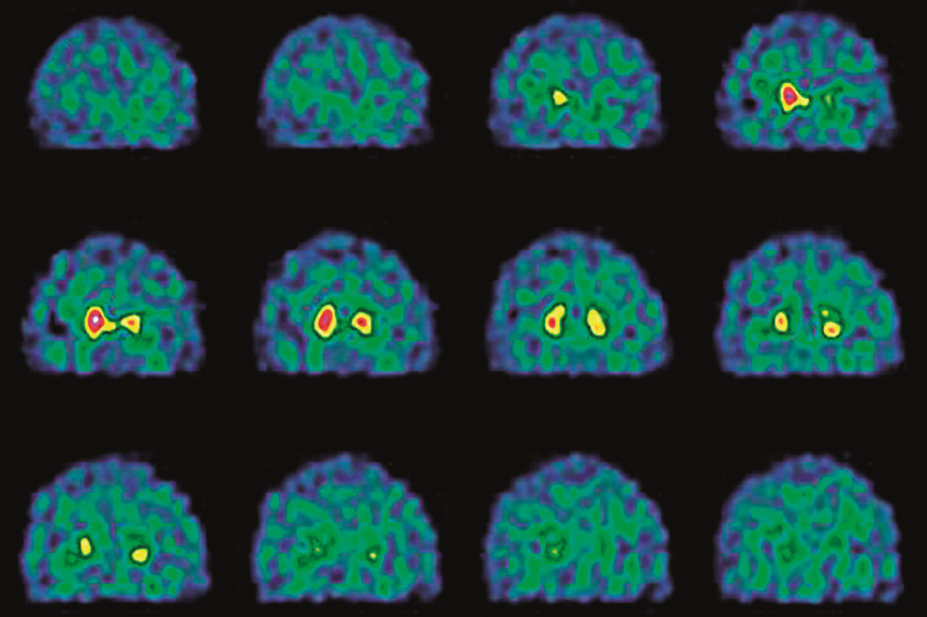

Diagnosis

PD is notoriously difficult to diagnose because patients present in different ways and there are no specific diagnostic tests available. Studies have found that diagnosis of PD in the community was incorrect in around 50% of patients, in up to 25% of patients in generalist care clinics and 6–8% in specialist clinics when diagnosed by an expert in movement disorders[1]

.

If PD is suspected, patients should be referred quickly and untreated to a specialist with expertise in the differential diagnosis of the condition[5]

.

After a formal diagnosis of PD has been made, patients should be reviewed regularly at 6–12-monthly intervals and if atypical clinical features develop, the diagnosis should be reconsidered[5]

. These reviews should be undertaken by a member of the specialist team (e.g. the pharmacist, nurse or consultant).

PD and many of its symptoms can be potentially mimicked by any drug that is able to block dopamine receptors. Neuroleptics are the most common cause of drug-induced parkinsonism, with the atypical neuroleptics (e.g. quetiapine and clozapine) being the best options in PD for the treatment of hallucinations and confusion when used cautiously (see Table 1). Metoclopramide and prochlorperazine should be avoided, and domperidone, cyclizine and ondansetron are the better treatments to manage nausea and vomiting in PD. In addition, care needs to be taken when prescribing antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotics and antihypertensives in PD — particularly the calcium channel-blocking drugs flunarizine and cinnarizine — as all these drug groups need careful monitoring[1],[13]

.

Table 1: Drugs to avoid (and use) when treating hallucinations and nausea in patients with Parkinson’s disease | |||

| Drug | Treatment of hallucinations/confusion | Treatment of nausea/vomiting | Vigilance required when using |

| Chlorpromazine | X | ||

| Fluphenazine | X | ||

| Perphenazine | X | ||

| Trifluoperazine | X | ||

| Flupenthixol | X | ||

| Haloperidol | X | ||

| Quetiapine | Y | ||

| Clozapine | Y | ||

| Metoclopramide | X | ||

| Prochlorperazine | X | ||

| Domperidone | Y | ||

| Cyclizine | Y | ||

| Ondansetron | Y | ||

| Antihistamines | Y* | ||

| Antidepressants | Y* | ||

| Antipsychotics | Y* | ||

| Antihypertensives (e.g. calcium channel blockers — flunarizine and cinnarizine) | Y* | ||

| X = not recommended; Y = recommended; Y* = vigilance required | |||

| Source: Parkinson’s UK. Parkinson’s: Key information for hospital pharmacists[13] | |||

Management

Before starting on any treatment, it is important to discuss with patients their individual clinical circumstances (e.g. symptoms and comorbidities). Their lifestyle preferences are also important, for example people in full-time employment often prefer to have a once-daily dosage regimen if possible. As all medicines for PD are symptomatic, with no neuroprotective agents currently available, treatment should only be initiated when quality of life is affected[5]

, and the potential benefits and side effects of these drug classes should be discussed with the patient (see Table 2)[5]

.

Table 2: Potential benefits and harms of levodopa, dopamine agonists and monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors | |||

| Levodopa | Dopamine agonists | MAO-B inhibitors | |

| Motor symptoms | More improvement in motor symptoms | Less improvement in motor symptoms | Less improvement in motor symptoms |

| Activities of daily living | More improvement in activities of daily living | Less improvement in activities of daily living | Less improvement in activities of daily living |

| Motor complications | More motor complications | Fewer motor complications | Fewer motor complications |

| Adverse events | Fewer specified adverse events* | More specified adverse events* | Fewer specified adverse events* |

| MAO-B: monoamine oxidase-B * Excessive sleepiness, hallucinations and impulse-control disorders (see the summary of product characteristics for full information on individual medicines) | |||

| Reproduced with permission from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017). Parkinson’s disease in adults [5] | |||

Initiating pharmacological treatment

A dopamine agonist, levodopa or a monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor can be offered to people in the early stages of PD whose motor symptoms do not impact on their quality of life[5]

.

Levodopa is the gold standard treatment when motor symptoms impact on quality of life, but after 7–10 years of disease progression, levodopa response can fluctuate and, therefore, be less effective at controlling motor symptoms[1]

. Pharmacists and healthcare professionals should be aware that patients with PD may experience bowel and salivary difficulties (as described by James Parkinson in his original 1817 essay[14]

). GI disturbances are a frequent non-motor feature in PD and exist in all stages of the disease[15]

, as well as dysphagia, delayed gastric emptying and constipation. Recognition of delayed gastric emptying is important because it has implications for the absorption and action of levodopa. There is also evidence of additional small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in PD, the cause of which is unknown, and this impairs the absorption of levodopa and contributes significantly to response fluctuations[16]

. For these reasons, non-oral therapies (e.g. patch formulation) are useful in PD management.

All dopaminergic medicines have the potential to cause impulse-control disorders and hallucinations. Dopamine agonists have the highest risk of impulse-control disorders[17]

, excessive sleepiness, sudden sleep onset and psychotic symptoms (e.g. hallucinations or delusions). Impulse-control disorders can include compulsive gambling, hypersexuality, binge eating and obsessive shopping. It is important that a patient has a point of contact (e.g. the specialist pharmacist or specialist nurse involved in their care) should any impulse-control disorders develop. Management of impulse-control disorders involves modifying dopaminergic therapy by first gradually reducing any dopamine agonist. If this is ineffective, specialist cognitive behavioural therapy can be offered. It is important that patients and carers or family members are given oral and written information about impulse-control disorders when dopamine agonist therapy is initiated and this should be discussed at review appointments[5]

.

Ergot-derived dopamine agonists (e.g. pergolide, bromocriptine and cabergoline) should only be offered as an adjunct to levodopa for people with PD who have developed dyskinesia or motor fluctuations despite optimal levodopa therapy and who have an inadequate response to a non-ergot agonist (e.g. ropinirole, pramipexole and rotigotine [patch]). However, the ergot-derived dopamine agonists are associated with severe fibrotic side effects that now limit their use. The oral non-ergot agonists (e.g. ropinirole and pramipexole) have the advantage that they can be prescribed as once-daily formulations. However, care needs to be taken when prescribing pramipexole in view of its availability as a base and a salt, with doses and strengths normally stated in terms of pramipexole base[18]

. All dopamine agonist doses should be increased gradually, and withdrawn gradually to prevent symptoms of dopamine withdrawal (see Table 3).

Table 3: Dopamine agonists and dose titration | ||||||

| Ropinirole | Ropinirole modified release | Pramipexole | Pramipexole modified release | Rotigotine monotherapy | Rotigotine (adjunctive therapy with levodopa) | |

| Dose | Initially 750µg daily in three divided doses | Initially 2mg once daily for one week, then 4mg once daily | Initially 88µg three times a day | Initially 260µg once daily | Apply 2mg/24 hour patch to dry, non-irritated skin on torso, thigh or upper arm, removing after 24 hours and siting replacement patch on a different area (avoid using the same area for 14 days) | Apply 4mg/24 hour patch to dry, non-irritated skin on torso, thigh or upper arm, removing after 24 hours and siting replacement patch on a different area (avoid using the same site for 14 days) |

| Dose frequency | Three times daily | Once daily | Three times daily | Once daily | Once daily | Once daily |

| Dose titration | Increased by increments of 750µg. Dose to be increased at weekly intervals up to 3mg daily in three divided doses, then increased in steps of 1.5–3mg, adjusted according to response. Dose to be increased at weekly intervals; usual range 9–16mg daily | Increased in steps of 2mg at intervals of at least one week, adjusted according to response, up to 8mg once daily. Dose to be increased further if still no response; increased in steps of 2–4mg at intervals of at least two weeks if required | Dose doubled every 5–7 days if tolerated to 350µg three times daily; further increased if necessary by 180µg three times daily at weekly intervals | Dose to be increased by doubling dose every 5–7 days, increased to 1.05mg once daily, then increased in steps of 520µg every week if required | Increased in steps of 2mg/24 hours at weekly intervals if required | Increased in steps of 2mg/24 hours at weekly intervals if required |

| Maximum dose | 24mg daily | 24mg per day | 3.3mg daily in three divided doses | 3.15mg per day | 8mg/24 hours | 16mg/24 hours |

| Source: BNF Publications. British National Formulary (75)[18] | ||||||

As well as a dopamine agonist prescription, there is an increased risk of developing impulse-control disorders if a patient with PD has a past history of impulsive behaviours or a history of alcohol consumption and/or smoking[19]

.

Switching to alternative drug treatments

A dopamine agonist, monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor or catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitor can be offered as an adjunct to levodopa for people with PD who have developed dyskinesia or motor fluctuations, despite optimal levodopa therapy (see Table 4). If dyskinesia is not adequately managed by modifying existing therapy, amantadine is often used in practice, although the current evidence for its use is limited (see Table 4).

Table 4: Potential benefits and harms of dopamine agonists, monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors, | ||||

| Dopamine agonists | MAO-B inhibitors | COMT inhibitors | Amantadine | |

| Motor symptoms | Improvement in motor symptoms | Improvement in motor symptoms | Improvement in motor symptoms | No evidence of improvement in motor symptoms |

| Activities of daily living | Improvement in activities of daily living | Improvement in activities of daily living | Improvement in activities of daily living | No evidence of improvement in activities of daily living |

| Off time | More off-time reduction | Off-time reduction | Off-time reduction | No studies reporting this outcome |

| Adverse events | Intermediate risk of adverse events | Fewer adverse events | More adverse events | No studies reporting this outcome |

| Hallucinations | More risk of hallucinations | Lower risk of hallucinations | Lower risk of hallucinations | No studies reporting this outcome |

| COMT: catechol-O-methyl transferase; MAO-B: monoamine oxidase-B. | ||||

| Reproduced with permission from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2017). Parkinson’s disease in adults. [5] | ||||

Importance of the multidisciplinary team

The updated National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance acknowledges the importance of a multidisciplinary team when managing PD, with referral suggested to therapists trained in the management of the condition, for example physiotherapy[20],[21],[22]

, occupational therapy[23]

, speech and language therapy[24],[25]

, and nutrition therapy[26],[27],[28]

. In addition, NICE has recommended further research aimed at investigating whether physiotherapy started early in the course of PD, as opposed to after motor onset, confers benefits in terms of delaying symptom onset and/or reducing severity.

The role of the pharmacist

In view of the age of onset of symptoms of PD, patients often have several comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and pharmacists are well-placed to manage the patient holistically and advise on any potential medicine interactions that could occur. This was demonstrated in a recent study involving a PD-specific medicines-use review pilot across eight pharmacies in London[29]

. In the pilot, patients welcomed the opportunity to talk to a pharmacist about their medicine concerns, in particular problems with non-motor symptoms, and a lack of understanding around their medicines and how they work[29]

.

A local audit of PD patients in Dudley in 2015 identified medication as the area that concerned patients most (unpublished data). Furthermore, the author has received excellent patient feedback from her own pharmacist-led PD clinics, which illustrates the level of patient satisfaction when a pharmacist is involved in PD management.

Community pharmacists, who often have excellent professional relationships with their patients and are easily accessible, as well as ward-based pharmacists across all specialties, are essential PD patient advocates. Furthermore, they are well placed to ensure that PD patients understand the importance of their PD medicine and that they are getting it on time as per the Parkinson’s UK ‘Get it on Time’ campaign[30]

.

An area where pharmacist input could also be important is in the management of drooling, which is often a problem for PD patients, and medicine is suggested by NICE if therapy has been unsuccessful. Glycopyrronium bromide[5]

(not licensed) should be considered to manage drooling of saliva because this has the lowest adverse cognitive effect of all the anticholinergics. If this is contraindicated or not tolerated, a referral for botulinum A toxin can be considered, although this is not a licensed indication. It is also worth noting that speech and language therapy is suggested for improving safety and efficacy of swallowing and minimising risk of aspiration.

Patients with PD have complex medication regimens, making pharmacists an essential source of information. However, more pharmacy-based research regarding the role of pharmacists in the management of PD is needed.

Palliative care

It is important to consider a referral to the palliative care team at any stage of PD to allow discussion about end-of-life care[31],[32],[33]

. Patients with PD and their carers should be offered oral and written information about disease progression, possible adverse effects, advance care planning, including advanced decisions to refuse treatment, ‘do not attempt resuscitation’ orders and lasting powers of attorney for finance and/or social care. It is also important to remember that family members or carers may have different information needs to the patient with PD.

Management of advanced PD

Deep brain stimulation may be considered for people with advanced PD[5]

but only when symptoms are not controlled with medical therapy, which may include intermittent apomorphine injection or continuous apomorphine subcutaneous infusion.

PD research areas recommended by NICE

Since completion of the current NICE PD guidelines, there are several research questions that are being investigated (including the aforementioned physiotherapy study[5]

).

Combination treatment for PD dementia

A cholinesterase inhibitor is suggested for people with mild-to-moderate or severe PD dementia. Rivastigmine is only licensed for mild-to-moderate dementia in PD[34]

. Memantine can be considered if a cholinesterase inhibitor is not tolerated or is contraindicated[35]

. A research question was designed to review the effectiveness of combination treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor and memantine for people with PD dementia if treatment with a cholinesterase inhibitor alone is not effective or is no longer effective.

Psychotic symptoms (hallucinations and delusions)

If psychotic symptoms occur, the PD medicine that may have triggered the hallucinations or delusions should be reduced. Quetiapine[36]

(not licensed) or clozapine[37]

can then be considered when registration with a patient-monitoring service is needed. A research recommendation was made to identify the effectiveness of rivastigmine compared with atypical antipsychotic drugs for treating psychotic symptoms associated with PD.

Orthostatic hypotension treatment

If the existing medicine is not causing or adding to postural hypotension, midodrine is suggested first line as the only licensed medicine for this indication. If midodrine is contraindicated, not tolerated or ineffective, fludrocortisone should be considered. As fludrocortisone[38]

tended to be prescribed first line for this indication prior to the licensing of midodrine, a research question has been set to find the most effective pharmacological treatment for PD patients with postural hypotension.

Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder treatment

Clonazepam[39]

or melatonin[39]

are suggested to manage rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder if a medication review has failed to identify any other pharmacological cause. However, neither medicine is licensed for this condition. Therefore, a research recommendation has been made to identify the best first-line treatment for REM sleep behaviour disorder in PD.

Conclusion

The cause of PD is not fully understood and treatment is symptomatic and involves multidisciplinary team care. When the NICE guidelines are next updated, a scoping question to review the role of the pharmacist in the management of PD should be added. It is important to build up a body of evidence to identify how important the role of the pharmacist is to this patient cohort because medication is often the most problematic area for them. Many of these patients are prescribed very complex medicine regimens and, therefore, a consultation with a healthcare professional who is an expert in medicines could be invaluable to them.

Financial and conflicts of

interest disclosure

The author was a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Parkinson’s disease guideline committee; however, the views expressed in this article are those of the author and not necessarily those of NICE. The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Opportunity

A Parkinson’s disease specialist pharmacist network is currently being developed to help upskill pharmacists in the management of Parkinson’s disease. Any pharmacist wishing to be involved can send their expression of interest via email to the author.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal. You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

References

[1] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summary-Parkinson’s disease (2018). Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/parkinsons-disease (accessed August 2018)

[2] Parkinson’s UK. The incidence and prevalence of Parkinson’s in the UK. Results from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/incidence-and-prevalence-parkinsons-uk-report (accessed August 2018)

[3] Kalia LV & Lang AE. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015;386(9996):896–912. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61393-3

[4] Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and pharmacological management of Parkinson’s disease (SIGN 113). 2010. Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/sign-113-diagnosis-and-pharmacological-management-of-parkinson-s-disease.html (accessed August 2018)

[5] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Parkinson’s disease in adults: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline [NG71]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng71 (accessed August 2018)

[6] Tanner CM, Ottman R, Goldman SM et al. Parkinson’s disease in twins: an etiologic study. JAMA 1999;281:341–346. doi: 10-1001/pubs.JAMA-ISSN-0098-7484-281-4-joc81035

[7] Fisher B, Wu A, Salem G et al. The effect of exercise training in improving motor performance and corticomotor excitability in people with early Parkinson’s disease. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;89(7):1221–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.01.013

[8] Quelhas R & Costa RD. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2009;21:413–419. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2009.21.4.413

[9] Parkinson’s UK. Pain in Parkinson’s. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/information-and-support/pain (accessed August 2018)

[10] Edwards M, Quinn N & Bhatia K. Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008. doi: 10.1093/med/9780198569848.001.0001

[11] Braak H, Tedici KD, Rub U et al. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2003;24(2):197–211. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00065-9

[12] Holmqvist S, Chutna O, Bousset L et al. Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol 2014;128(6):805–820. doi: 10.1007/s00401-014-1343-6

[13] Parkinson’s UK. Parkinson’s: Key information for hospital pharmacists. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/professionals/resources/parkinsons-key-information-hospital-pharmacists (accessed August 2018)

[14] Parkinson J. An essay on the shaking palsy. J Neuropsychiatry and Clin Neurosci 2002;14:223–236. doi: 10.1176/jnp.14.2.223

[15] Pfeiffer RF. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2011;17(1):10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2010.08.003

[16] Tan AH, Mahadeva S, Thalha AM et al. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2014;20(5):535–540. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2014.02.019

[17] Weintraub D, Koester J, Potenza MN et al. Impulse control disorders in Parkinson disease: a cross sectional study of 3090 patients. Arch Neurol 2010;67:589–595. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.65

[18] BNF Publications. British National Formulary (75). Available at: http://www.bnf.org (accessed August 2018)

[19] Sharma A, Goyal V, Behari M et al. Impulse control disorders and related behaviours (ICDRBs) in Parkinson’s disease patients: assessment using “Questionnaire for impulsive-compulsive disorders in Parkinson’s disease” (QUIP). Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2015;18:49–59. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.162306

[20] Canning CG, Allen NE Dean CM et al. Home-based treadmill training for individuals with Parkinson’s disease: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Clin Rehabil 2012;26:817–826. doi: 10.1177/0269215511432652

[21] Cholewa J, Boczarska-Jedynak MFAU & Opala G. Influence of physiotherapy on severity of motor symptoms and quality of life in patients with Parkinson disease. Neurol Neurochir Pol 2013;47:256–262. doi: 10.5114/ninp.2013.35774

[22] Amano S, Nocera JR, Vallabhajosula S et al. The effect of Tai Chi exercise on gait initiation and gait performance in persons with Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19(11):955–960. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2013.06.007

[23] Sturkenboom IH, Graff MJ, Hendriks JC et al. OTiP study group. Efficacy of occupational therapy for patients with Parkinson’s disease: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol 2014;13:557–566. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70055-9

[24] Herd CP, Tomlinson CL, Deane KHO et al. Speech and language therapy versus placebo or no intervention for speech problems in Parkinson’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;8:CD002812. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002812.pub2

[25] Troche MS, Okun MS, Rosenbek JC et al. Aspiration and swallowing in Parkinson’s disease and rehabilitation with EMST: a randomized trial. Neurol 2010;75:1912–1919. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fef115

[26] Croxson S, Johnson B, Millac P et al. Dietary modification of Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Clin Nutr 1991;45:263–266.

[27] Nathan J, Panjwani S, Mohan V et al. Efficacy and safety of standardized extract of Trigonella foenumgraecum l seeds as an adjuvant to L-dopa in the management of patients with Parkinson’s disease. Phytother Res 2014;28(2):172–178. doi: 10.1002/ptr.4969

[28] Storch A, Jost WH, Vieregge P et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial on symptomatic effects of coenzyme Q(10) in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol 2007;64:938–944. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.7.nct60005

[29] Bancroft S. Parkinson’s disease-specific medicines use review. Clinical Pharmacist 2017;9(1):11. doi: 10.1211/CP.2016.20201923

[30] Parkinson’s UK. Get it on time. Available at: https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/get-involved/get-it-time (accessed August 2018)

[31] Kristjanson LJ, Aoun SM & Oldham L. Palliative care and support for people with neurodegenerative conditions and their carers. Int J Palliat Nurs 2006;12:368–377. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2006.12.8.368

[32] Hasson F, Kernohan WG, McLaughlin M et al. An exploration into the palliative and end-of-life experiences of carers of people with Parkinson’s disease. Palliat Med 2010;24(7):731–736. doi: 10.1177/0269216310371414

[33] Kwak J, Wallendal MS, Fritsch T et al. Advance care planning and proxy decision making for patients with advanced Parkinson disease. South Med J 2014;107(3):178–185. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0000000000000075

[34] Emre M, Aarsland D, Albanese A et al. Rivastigmine for dementia associated with Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:2509–2518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041470

[35] Aarsland D, Ballard C, Walker Z et al. Memantine in patients with Parkinson’s disease dementia or dementia with Lewy bodies: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:613–618. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70146-2

[36] Fernandez HH, Okun MS, Rodriguez RL et al. Quetiapine improves visual hallucinations in Parkinson disease but not through normalization of sleep architecture: results from a double-blind clinical-polysomnography study. Int J Neurosci 2009;119:2196–2205. doi: 10.3109/00207450903222758

[37] Pollak P, Tison F, Rascol O et al. Clozapine in drug induced psychosis in Parkinson’s disease: a randomised, placebo controlled study with open follow up. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004;75:689–695. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.029868

[38] Schoffer KL, Henderson RD, O’Maley K et al. Nonpharmacological treatment, fludrocortisone, and domperidone for orthostatic hypotension in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2007;22:1543–1549. doi: 10.1002/mds.21428

[39] Gugger JJ & Wagner ML. Rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Ann Pharmacother 2007;41(11):1833–1841. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H587