JL / Shutterstock.com

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness. This is achieved through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems[1]

.

Palliative care is often considered to be only for patients with cancer, but it also incl udes patients with conditions such as organ failure (e.g. heart failure

, COPD, renal and hepatic failure), neurological conditions (e.g. multiple sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease and motor neurone disease), dementia, frailty, stroke and HIV/AIDS[2],[3],[4]

.

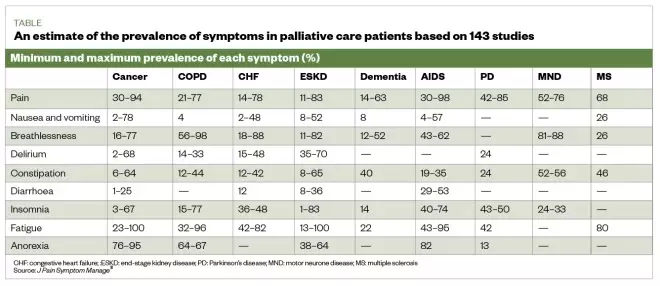

The same can be said when considering symptoms (see Table)[5]

. Being symptom-free is one of the most important factors for patients when considering end-of-life care[6]

. Pharmacists have much to offer, not only in providing medicines required for symptom management, but also supporting patients and their carers to receive the right care at the right time[2],[7],[8]

.

Table: an estimate of the prevalence of physical symptoms in palliative patients based on results from 143 studies

Source: J Pain Symptom Manage[5]

Symptom management

How symptoms are treated may change over time and may depend on many factors, including the symptom being treated, the patient’s ability to swallow (owing to disease process causing fatigue and weakness), and level of consciousness. Although most symptoms can be treated with oral preparations, it is likely that the oral route will become less available and a switch to parenteral preparations may be required.

The Gold Standards Framework recommends considering anticipatory prescribing of subcutaneous formulations for pain, nausea and vomiting, agitation/restlessness and excess respiratory secretions (also known as ‘death rattle’)[9],[10]

. The anticipatory prescribing of these medicines is part of advance care planning (i.e. the conversation between the patient’s families and carers about their future wishes and priorities for care)[11],[12]

.

The way symptoms are treated in patients receiving palliative care may change over time; however, several factors may influence this. For example, the Gold Standards Framework recommends considering subcutaneous formulations for:

- Pain;

- Nausea and vomiting;

- Agitation/restlessness;

- Excess respiratory secretions[12]

.

Pharmacy schemes across the UK exist to act as stockists for locally selected anticipatory medicines, including alternative anti-emetics, opiates and steroids. See the Local Pharmaceutical Committee website for details (see Useful resources). Be aware of the local pharmacies enrolled in these schemes, to ensure the pharmacy team can advise patients or carers if needed.

The Gold Standards Framework also suggests five steps for healthcare professionals to consider when advance care planning for patients, which are:

- Thinking about the future and what is important to the patient;

- Talking with family and friends about the patient’s choices so they are aware of them and can act as a spokesperson should the patient become unable to do this for themselves;

- Recording the patient’s wishes;

- Discussing plans with healthcare teams involved in the patient’s care (this may include conversations about resuscitation);

- Sharing information with the people who will need to be aware of it[12]

.

An advance care plan can include many details, such as the desired extent of active treatment; the patient’s preferred place of care at the end of life; preferences for symptom management (e.g. the level of sedation a patient finds acceptable); people they would like to be present at end of life; spiritual and religious needs; and thoughts around funeral planning.

The Palliative Care Formulary provides excellent information and guidance on dosing and routes, which are often outside of the product license[10]

. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has also published several documents to support healthcare professionals in their approach to palliative care[13]

(see Useful resources).

Role of the pharmacist

Towards the end of a patient’s life, drug treatments should be as minimised when possible, with pharmacists reviewing and advising on deprescribing[7],[14]

. Pharmacists should also support patients in fulfilling their wishes to die in the place they choose with their symptoms well managed[8]

.

The role of pharmacists in palliative care should be much greater than a supply function, although the importance of stocking anticipatory medicines should not be underestimated. Patients and their carers value more than the basic level of service from the pharmacy, and appreciate friendliness from staff who are familiar with them and can provide support with medicines and symptom management[15]

.

The complex and often changing medicines regimens for palliative care patients can be challenging for medicines optimisation. Providing clear instructions on regimens and general communication can help (see Box 1)[10]

. It is important to establish what medicines the patient is taking and when, and support and simplify their regimen if possible. For example, a patient is instructed to take paracetamol 1,000mg four times a day at 08:00, 12:00, 16:00 and 20:00, but wakes during the night with pain. Instead, the patient could be advised to take the paracetamol at equal intervals throughout the 24-hour period, (e.g. every six hours)[10]

. However, this decision would need to take into consideration the patients waking hours and preferences.

The following case describes how pharmacists can assist patients nearing end of life with management of pain, nausea and constipation, and anticipatory prescribing.

Box: Considerations to take into account when communicating with palliative care patients and carers

Aims of communication:

- Information sharing;

- Reducing uncertainty;

- Facilitating choices and joint decision making;

- Creating, developing and maintaining relationships.

Getting started:

- Make time for the conversation, even if it is only for a few uninterrupted minutes;

- Ensure privacy;

- Introduce yourself;

- Indicate clearly that you have time to listen (e.g. offer to sit down with them);

- Use open questions to obtain information and allow the patient to talk (e.g. “what do you think this medicine is for?”);

- Engage using active listening (e.g. nodding and summarising to check information).

Be aware of non-verbal communication, such as:

- Facial expression;

- Eye contact;

- Posture (whether sitting or standing);

- Pitch and pace of voice;

- Use of appropriate touch.

Try to recognise barriers to good communication, for example:

- Language (patient’s own language or the use of jargon);

- Poor hearing, feeling generally unwell, fatigued, distracted by symptoms, fear and anxiety;

- Poor transfer of care information;

- Lack of time and privacy.

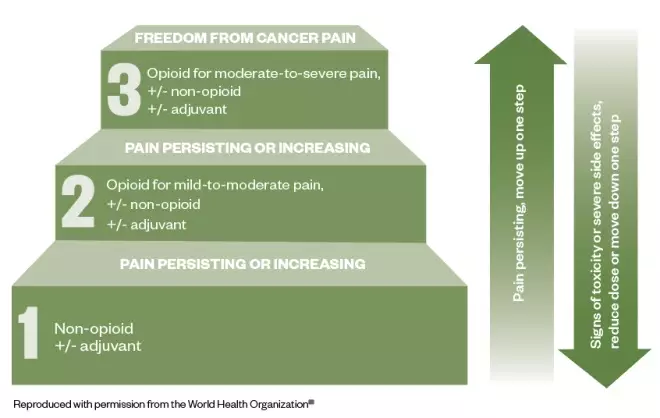

Figure: the three-step analgesic ladder

Source: World Health Organization[16]

This cancer pain management ladder provides a general guide to treatment based on the severity of pain

Case study

Palliative care part 1: pain management

Mary*, aged 54 years, comes into the pharmacy and asks to speak to the pharmacist about her prescribed medicines. She was recently diagnosed with metastatic pancreatic cancer, and her GP and palliative care team are working to manage her pain.

Two weeks ago, Mary was started on paracetamol 1,000mg four times per day and morphine sulphate liquid 5mg (2.5mL) every two to four hours as required. She was previously prescribed codeine 30–60mg four times per day, but this did not help to relieve her symptoms. On average, she has been taking six doses of morphine sulphate 5mg in each 24-hour period, and although this helps, it does not completely alleviate her pain.

Today, Mary has been prescribed morphine sulphate (MST; Napp Pharmaceuticals) 15mg twice daily and has been told to continue with her paracetamol and morphine sulphate liquid (for breakthrough pain). Mary explains that her GP said there may be a need to add a medicine for nerve pain. However, Mary goes on to say that she is worried that she is taking “too much” medicine and she is reluctant to take all of these medicines, especially if another may be added for nerve pain.

Actions and recommendations

The pharmacist should consider the following during the consultation:

- Communication — open questions should be used to determine how much has been explained to Mary about pain management. It may be that she has been given an explanation, but it is often worth covering these again;

- World Health Organization pain ladder — explain the use of the ladder (see Figure), including the need to use regular paracetamol;

- Analgesia — patients are often concerned by using more than one opiate. Patients may need to be encouraged to use their breakthrough analgesia when required, explaining how the dose is determined by the background analgesia may help[17]

; - Keeping a diary — Mary should be encouraged to keep a pain diary. This can be a benefit as keeping a record of breakthrough doses may help when it comes to dose titration;

- Addressing patient concerns — explain to Mary that neuropathic agents may be used as an adjuvant if opiates fail to control the pain[18]

; - Resources — recommend available online resources to Mary through the British Pain Society and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (see Useful resources)[17],[19]

.

Explain to Mary that as her opiate dose is increased, breakthrough doses will also increase. These should be one-sixth of the total daily opiate dose. For example, a dose of MST 30mg twice daily (60mg/24 hours), will require morphine sulphate (liquid or tablet) 10mg every 2–4 hours as required for breakthrough pain[10],[14]

.

When to refer

Mary should be referred back to her GP or the palliative care team if she requires frequent prescriptions for breakthrough medicines, which would indicate that her pain is not adequately managed, or she is experiencing unacceptable side effects (e.g. nausea or severe itch).

Palliative care part 2: nausea and constipation

Mary returns to the pharmacy ten days after starting on MST and her background dose is currently 30mg twice daily. She says that her pain is controlled, but she has been experienced nausea since the MST dose was increased two days ago. She also explains that she has not had “a proper bowel movement” for five days. Mary says she feels generally uncomfortable and has a feeling of fullness in her abdomen.

As a result, Mary is considering stopping the MST capsules. When questioned on her diet, Mary says she understands that dietary intake influences her bowels; however, she explains that her appetite is reduced owing to the abdominal discomfort. Mary would like to know if there is anything she can purchase that will help.

Actions and recommendations

Constipation is the most commonly reported side effect of opiate treatment (up to 80% of patients) and can result in reduced quality of life and discontinuation of the offending medicine, which could result in a resurgence of pain[10],[20]

. When speaking with Mary about management, consider the following:

- Ascertain bowel pattern — the Bristol Stool chart can be used to support the consultation, but it is important to determine what is ‘normal’ for the patient and any other symptoms (e.g. colic)[21]

. Mary confirms that her bowels feel sluggish and she is passing small, hard stools, which requires a lot of effort.; - Maintaining a healthy diet — Mary’s dietary intake is reduced, but with resolution of constipation, this may improve. Encourage a healthy diet that includes whole grains, fruit and vegetables, and a good fluid intake[22]

; - Laxatives — regular administration of laxatives to avoid constipation is advised[14]

. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends the use of: stimulant laxatives (e.g. Senna [7.5–15mg at night, increasing to 30mg maximum in 24 hours] and sodium picosulphate [5–10mg at night]) and osmotic laxatives (e.g. lactulose [15–45mL daily in three divided doses] and macrogol compound [1–3 sachets daily in divided doses])[22]

. Docusate (up to 500mg daily in divided doses) is an alternative as both a softener and weak stimulant[10]

. If tolerance to constipation does not occur, treatment with laxatives is advised for the duration of opiate use[20]

. If titration of laxative is required then this occurs every 1–2 days according to response before switching to an alternative[10]

; - Nausea — this common side effect occurs on initiation and dose increase, but is normally transient, lasting only a few days[15],[23],[24]

. If patients are aware of this, they may feel more prepared and willing to accept it for a short period of time making the use of an antiemetic unnecessary[20]

; - Non-pharmacological measures — pharmacy teams can recommend removal of certain stimuli (e.g. sight and smell of nausea-provoking foods) that lead to nausea and massage to help manage constipation[25],[26]

.

It is important to explain to Mary that opioid analgesics are a common cause of constipation, alongside other contributing factors, such as poor fluid, and dietary intake[27]

.

Compliance with laxatives may be limited by patient factors, such as palatability, volume required and undesirable effects (e.g. flatulence and colic). Mary’s preference should be considered, especially as there is limited evidence for the use of laxatives, and management is generally dictated by best practice and expert opinion[14]

.

The underlying aetiology of nausea and/or vomiting should be considered; gastric dysmotility and stimulation of the chemoreceptor trigger zone are most common with opiates, and can be managed with prokinetics (e.g. domperidone, metoclopramide) or a D2 receptor antagonist (e.g. haloperidol)[10],[18]

,[19]

.

When to refer

When the maximum licensed dose of laxatives is reached without adequate result, then there is a need to refer the patient.

If an antiemetic is considered necessary (e.g. owing to persistent or intolerable nausea), the patient requires referral for thorough assessment[25]

.

Palliative care part 3: Anticipatory prescribing

Mary’s husband, John*, brings a prescription for anticipatory medicines into the pharmacy. He is visibly upset and asks to speak to the pharmacist. He explains that the GP surgery called and asked for this prescription to be collected following a home visit from Mary’s community nurse.

During the visit, the nurse asked difficult questions about where Mary would like to be cared for when she becomes less well, and whether she would want to be resuscitated. The nurse had also suggested that Mary can stop her simvastatin, which she has been taking for the past 17 years.

John’s concerns

Although John is concerned because he knows Mary is unwell, he thinks these conversations suggest that Mary is nearing the end of her life.

Actions and recommendations

When speaking with John, be empathetic while providing information. For example, explain:

- That anticipatory prescribing is part of advance care planning and does not signify that a patient is imminently dying. Medicines are prescribed in anticipation of symptoms, and should be put in place well in advance to enable rapid symptom relief[13],[28]

; - The possible use for each of the medicines (pain, nausea and vomiting, excess respiratory secretions, agitation and restlessness)[29]

. It is unlikely that all would be needed, and possibly none at all. These medicines can be used for a more acute symptom, such as nausea or pain owing to infection, rather than only for use in the last few days of life; - Stopping unnecessary medicines (i.e. those for long-term risk, such as statins for cardiovascular disease) should be considered to reduce tablet burden and potential side effects[7]

; - These conversation can be distressing, but it provides an opportunity to consider serious issues during a time that is less critical and that some patients and carers may find comfort in the planning[30]

.

After speaking with and explaining these points to John he appears to be more content and less worried. It is important to explain to him that the pharmacy team is available to speak to him or his wife if they have any further concerns.

*Case study is fictional

Useful resources

- Local Pharmaceutical Committee: lpc-online.org.uk/

- The Pharmaceutical Journal. Facilitating anticipatory prescribing in end-of-life care.

References

[1] World Health Organization. WHO definition of palliative care. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed October 2019)

[2] World Health Organization. Palliative care. 2018. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/palliative-care (accessed October 2019)

[3] The Gold Standards Framework. PIG – Proactive identification guidance registration form. 2016. Available at: http://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/PIG (accessed October 2019)

[4] Marie Curie. Triggers for palliative care. 2015. Available at: https://www.mariecurie.org.uk/globalassets/media/documents/policy/policy-publications/june-2015/triggers-for-palliative-care-full-report.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[5] Moens K, Higginson IJ & Harding R. Are there differences in the prevalence of palliative care-related problems in people living with advanced cancer and eight non-cancer conditions? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manag 2014;48(4):660–677. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.11.009

[6] Kobewka D, Ronksley P, McIssac D et al. Prevalence of symptoms at the end of life in an acute care hospital: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open 2017;5(1):E222–E228. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20160123

[7] Walker KA, Scarpaci L & McPherson ML. Fifty reasons to love your palliative care pharmacist. American J Hosp Palliat Care 2010;27(8):511–513. doi: 10.1177/1049909110371096

[8] Macmillan Cancer Support. The Final Injustice: variation in end of life care in England. 2017. Available at: https://www.macmillan.org.uk/_images/MAC16904-end-of-life-policy-report_tcm9-321025.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[9] The Gold Standards Framework. Examples of Good Practice Resource Guide. Just in Case Boxes. 2006. Available at: https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/Library%2C%20Tools%20%26%20resources/ExamplesOfGoodPracticeResourceGuideJustInCaseBoxes.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[10] Twycross R, Wilcock A & Howard P. Palliative Care Formulary 6th Ed (PCF6). 2016. Available at: https://about.medicinescomplete.com/publication/palliative-care-formulary (accessed October 2019)

[11] National Palliative and End of Life Care Partnership. Ambitions for palliative and end of life care. 2015. Available at: http://endoflifecareambitions.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Ambitions-for-Palliative-and-End-of-Life-Care.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[12] Gold Standard Framework. Advance Care Planning. 2018. Available at: https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/advance-care-planning (accessed October 2019)

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. NICE guideline [NG31]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng31 (accessed October 2019)

[14] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. British National Formulary 76. London: Pharmaceutical Press; 2001

[15] Edwards Z, Blenkinsopp A, Ziegler L & Bennett MI. How do patients with cancer pain view community pharmacy services? An interview study. Health Soc Care Community 2018;26(4):507–518. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12549

[16] World Health Organization. WHO’s cancer pain ladder for adults. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/painladder/en/ (accessed October 2019)

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Palliative care for adults: strong opioids for pain relief. NICE guideline [CG140] 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg140/ifp/chapter/Managing-side-effects (accessed October 2019)

[18] The British Pain Society. Cancer pain management. 2010. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/static/uploads/resources/files/book_cancer_pain.pdf (accessed October 2019)

[19] The British Pain Society. Patient publications. Available at: https://www.britishpainsociety.org/british-pain-society-publications/patient-publications/ (accessed October 2019)

[20] Rogers E, Mehta S, Shengelia R, & Carrington Reid M. Four strategies for managing opioid-induced side effects in older adults. Clin Geriatr 2013;21(4). PMID: 25949094

[21] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical knowledge summary. Constipation in adults. 2019. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/constipation#!scenarioRecommendation:1 (accessed October 2019)

[22] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG99]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99/resources/cg99-constipation-in-children-and-young-people-bristol-stool-chart-2 (accessed October 2019)

[23] NHS. Morphine. 2018. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/morphine/# (accessed October 2019)

[24] Cherny N, Ripamonti C, Pereira J et al. Strategies to manage the adverse effects of oral morphine: An evidence-based report. J Clin Oncol 2001;19(9):2542–2554. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2542

[25] Chand S. Nausea and vomiting in palliative care. Pharm J 2014;292(7799)240. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2014.11135047

[26] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Clinical Knowledge Summary. Palliative care — nausea and vomiting. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/palliative-care-nausea-and-vomiting (accessed October 2019)

[27] Watson M, Lucas C, Hoy A & Back I. Oxford Handbook of Palliative Care. Oxford University Press; 2005.

[28] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Care of dying adults in the last days of life. Quality standard [QS144]. 2017. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs144 (accessed October 2019)

[29] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Medicines guidance: prescribing in palliative care. Available at: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/guidance/prescribing-in-palliative-care.html (accessed October 2019)

[30] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). End of life care for adults. 2017. Quality Standard [QS13]. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs13 (accessed October 2019)

You might also be interested in…

Patient access to 24/7 palliative care medicines is ‘insufficient’, finds House of Commons-commissioned report

Lead paediatric palliative care pharmacists should be part of local plans, says RPS