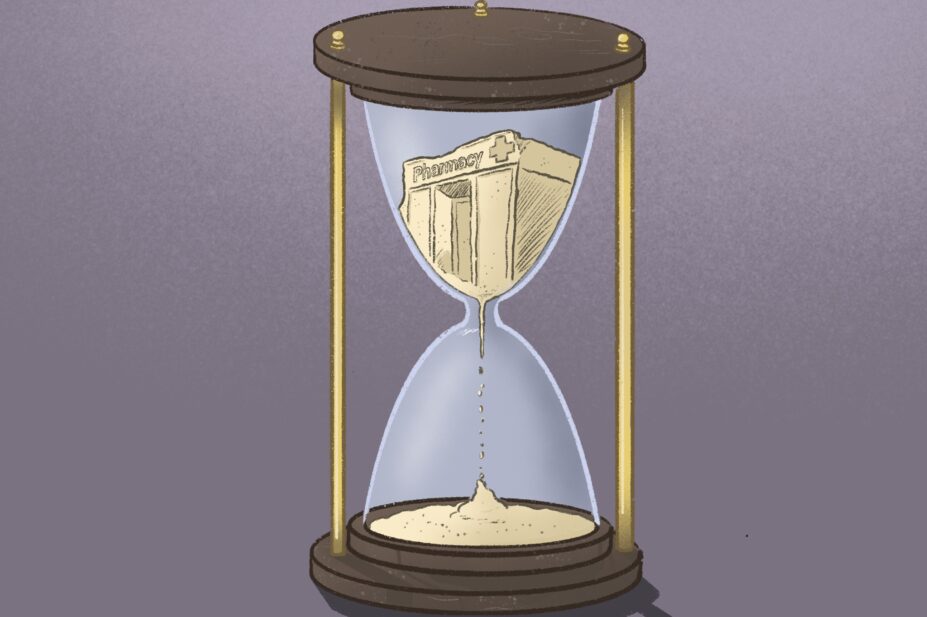

Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

An election manifesto for community pharmacy, issued in March 2024 and backed by the Royal Pharmaceutical Society, Community Pharmacy England, the National Pharmacy Association and the Company Chemists’ Association, makes familiar requests of the next UK government: more funding, more staff, fewer medicine shortages, more clinical services and greater focus on preventative care.

Without these fundamental changes — particularly around funding — “patients will experience an accelerating decline in their ability to access medicines, healthcare services and advice”, the manifesto says.

The shrinking community pharmacy network is a persistent, well-documented problem. According to the latest NHS Business Services Authority data on pharmacy openings and closures, there were 10,613 community pharmacies operating in England at the end of January 2024. This is the smallest the community pharmacy market has been since 2008/2009, when NHS Digital recorded 10,475 pharmacies. The market later peaked at 11,949 pharmacies in 2015/2016 and has been in decline ever since.

Pharmacy closures — driven by underfunding — are making it increasingly difficult for patients to access the care they need

As the manifesto highlights, these closures — driven by underfunding — are making it increasingly difficult for patients to access the care they need, particularly in deprived areas where pharmacies are shutting down at a faster rate.

But there are ways pharmacies are trying to save their business before closing altogether — all of which have their own detrimental impact on patient access that could be avoided with some extra cash.

We have reported on contractors offering more private services, while others are turning down the option of providing advanced services to focus on giving their patients a robust core offering of essential services and dispensing.

For the first time, The Pharmaceutical Journal can also reveal that pharmacies are reducing their opening hours in an effort to stay in business. More than a fifth of pharmacies in England cut back by an average of 10 hours per week between December 2022 and December 2023, with the number of pharmacies open for 100 hours or more decreasing by 80% in that time.

Between 2005 and 2012, so-called ‘100-hour’ pharmacies were a popular option for contractors looking to join the pharmaceutical list, because these contracts were exempt from having to prove that the pharmacy was “necessary or expedient” and could therefore open more easily. Dispensing and providing services over a longer time period paid for the additional workforce needed to cover the longer opening hours. Data show that 2,656 pharmacies took advantage of the exemption while it lasted, but years of government underinvestment, including frequently dispensing at a loss, has made this an unviable business model and has forced most to reduce their hours.

Ultimately, as ever, the most vulnerable patients are among the worst affected.

While many working people can make the most of the proliferation in online pharmacies and have repeat prescriptions delivered to their home, shorter opening times makes access to medicines for palliative and end-of-life care more difficult than it should be for those receiving this care at home.

Of the many challenges a patient faces in preparing for the end of their life, this should not be one of them

This care is already far from perfect. A report from the Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, published in 2021, found that although 80% of people would prefer to die at home, fewer than 50% do in some parts of England and Wales because the right services are not available to support them. This includes pharmacy services. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines on end-of-life care for adults, published in 2019, said being able to obtain medicines “outside of traditional working hours” was a “common concern” and recommended that all patients and their carers have access to “an out-of-hours pharmacy service that has access to medicines for symptom management”.

However, the House of Commons Health and Social Care Select Committee said in its report on assisted dying in February 2024 that it was “very concerned” to learn that patients were still finding it difficult to access appropriate end-of-life care, citing a 2022 Marie Curie report that warned that patients “frequently struggle to access pharmacies out of hours”.

Of the many challenges a patient faces in preparing for the end of their life, this should not be one of them. Pharmacists have the trust, expertise and tools needed to supply palliative and end-of-life medicines. In May 2023, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) and Marie Curie jointly published ‘The Daffodil Standards’ to help community pharmacies consistently offer the best end-of-life care to their patients. Standard 6 — to proactively manage medicine access — dovetails with the Pharmacy Quality Scheme incentive for pharmacies to have an action plan by 31 March 2024 for when they do not have stock of “the 16 critical medicines for palliative and end-of-life care”.

These are both significant steps towards improving palliative care in the community. But having medicines in stock and the guidelines to support patients are little use when the pharmacy cannot afford to stay open long enough to assist them late into the night.

This is just one of many ways the five-year ‘Community Pharmacy Contractual Framework’ — which ends on 31 March 2024 — has quietly chipped away at the care that community pharmacists can offer patients. All eyes are now on the negotiations between Community Pharmacy England, the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England for a new pharmacy contract in the coming months that endeavours to rebuild the sector. PJ

You may also be interested in

Patient access to 24/7 palliative care medicines is ‘insufficient’, finds House of Commons-commissioned report

Lead paediatric palliative care pharmacists should be part of local plans, says RPS