Wendy K Smith

It is common for patients to present to the community pharmacy complaining of an issue with their ears[1]

. However, because patients do not present directly to the pharmacist in every interaction in the pharmacy, the entire pharmacy team should be aware of what they can do to help. This article provides a framework to aid the diagnosis and appropriate management of ear discharge, earache, dizziness, vertigo and imbalance, based on patient symptoms and the limited examination that can be performed in a pharmacy.

The main questions that will help pharmacy teams have impactful consultations with patients presenting with ear symptoms are included in the Table. A patient may complain of a specific symptom, but asking about any co-existing issues will allow the pharmacist to determine the most likely cause and, therefore, the suitable treatment.

The extended role of the pharmacist, particularly in the community or within GP surgeries and acute medical assessment units, is an exciting development. Pharmacists having an increased understanding of conditions that commonly affect the ear, as well as an awareness of symptoms that may indicate a potentially rare or more serious diagnosis, will enable some patients with ear problems to be appropriately managed without a referral. Pharmacists with independent prescribing capabilities could prescribe and dispense medicines directly to the patient, when appropriate, thereby reducing the burden on GPs and ensuring treatment is started earlier for the patient.

| Presenting complaint | Follow-up questions | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| “I have some discharge from my ear” | “How long has it been present for?” | Some patients may only experience discharge for a few hours. In children, severe pain that reduces with the onset of the discharge may be a sign of acute otitis media. Prolonged discharge can occur in patients with otitis externa, but other conditions, such as cholesteatoma (skin growing in the wrong place), may need to be considered. |

| “Is it continuous or intermittent?” | Intermittent discharge occurs in children with recurrent acute otitis media, but some patients with a perforated eardrum can have a continuous or intermittent sticky discharge. In addition, those with otitis externa can experience a continuous or intermittent discharge. | |

| “Is it sticky or watery?” | Sticky discharge indicates an exudate from the middle ear. Watery discharge is a transudate resulting from inflammation/infection of the outer ear canal, as seen in otitis externa. | |

| “I have a painful ear” | “Where is the pain — deep in the ear, in front or behind the ear?” | Pain in the front of the ear may be from the temporomandibular joint. Sometimes, pain behind the ear originates from where the neck muscles attach to the skull. A deep pain may be referred from the mouth, throat or sinuses. |

| “Is it a dull ache, throbbing or sharp pain?” | Inflammatory conditions such as in otitis externa and acute otitis media may cause a throbbing pain, usually exacerbated at night as a result of engorgement of the tissues from lying in the recumbent position. Referred pain may be a dull ache or, if it is neurological in nature, a sharp pain. | |

| “Do you have any associated symptoms, such as a sore throat or oral problems?” | This may help locate the source of any referred pain. | |

| “I feel dizzy” | “Is there spinning or the sensation of movement?” | This could be owing to possible vestibular cause. |

| “Do you feel lightheaded or faint?” | This could be owing to a possible cardiovascular cause. | |

| “How long does the spinning last?” | If only a few seconds, it could indicate benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), whereas if it has lasted for a few hours, this may indicate manières (a condition of the inner ear causing sudden attacks of vertigo, tinnitus, feeling of pressure deep inside the ear and hearing loss). A spinning sensation lasting for days may indicate labyrinthitis or vestibular neuronitis — with or without hearing loss, respectively. | |

| “Did something trigger the sensation?” | Symptoms on movement, such as turning over in bed or looking up/down, would suggest BPPV, whereas symptoms on standing would indicate a postural drop in blood pressure. | |

| Source: BMJ [2] | ||

Discharge

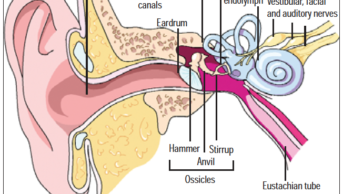

Patients may complain of having discharge from their ear. This may sometimes be the drainage of ear wax or water that has previously entered the ear canal, but asking whether the discharge appears to be sticky (like pus) or if it is foul-smelling can help determine the likelihood of infection. These characteristics indicate that it would be an exudate produced by cells in the middle ear, which typically occurs in children who have had a temperature with an acute viral ear infection. Ear infections owing to acute otitis media occur most commonly in the first year of life[3]

.

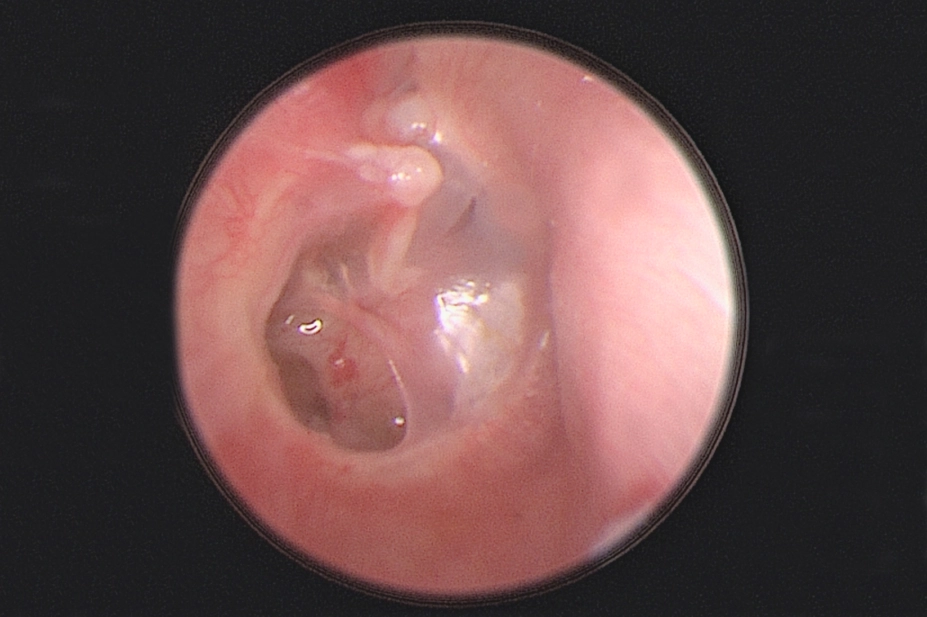

Patients with a perforated tympanic membrane may experience discharge — particularly if water enters the ear. The eardrum may perforate following an ear infection, but perforation may also be owing to an injury (i.e. a cotton bud being pressed too deep into the ear canal), changes in ear pressure or a sudden loud noise (such as an explosion)[4]

. A perforated eardrum may be accompanied by hearing loss, earache, ear itching and/or tinnitus. If the eardrum perforates in acute otitis media, pus typically drains from the ear and the pain usually settles quickly. Most perforated eardrums heal within a few weeks[4]

.

Patients, especially adults, with recurrent or persistent foul-smelling sticky discharge may have developed a condition called cholesteatoma (a non-cancerous, abnormal skin growth in the middle ear/mastoid). These patients may, therefore, require referral to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist[5]

.

Adults sometimes describe the presence of a watery discharge (a transudate), which is produced from the wall cells of the outer ear canal. These patients often admit to using cotton buds or other objects to ‘clean’ or itch their outer ear canal. Patients must be advised against doing this since the skin of the ear canal is very thin and can be easily traumatised, resulting in otitis externa. This could be caused by inflammation or an infection of the outer ear canal which could either be bacterial (for example Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomonas aeruginosa) or fungal (for example Candida spp.).

Management

People with an ear infection or otitis externa should take precautions around water, including when showering or washing the hair. ENT surgeons recommend that patients use a single-use cotton wool ball coated in petroleum jelly to cover the ear canal when showering, to prevent water entering the ear. Although swim moulds and plugs are available, their re-use can cause a persistent or repeat infection, as can the use of in-ear headphones. Patients should also pay attention to hand hygiene to prevent cross-infection between ears.

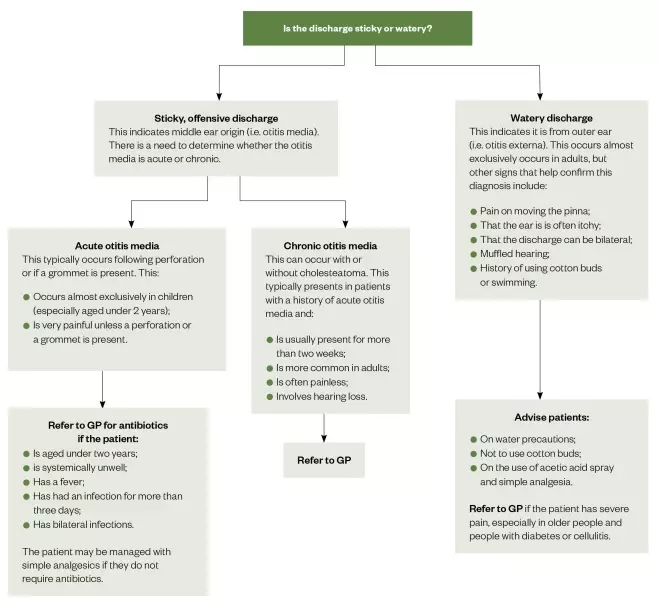

Acute otitis media in children can often be managed with simple analgesia, such as paracetamol and ibuprofen. However, they should be referred to their GP if:

- They are aged under two years;

- They are systemically unwell (e.g. they have a fever);

- The infection has been present for more than three days;

- They have bilateral infections[6]

.

Patients with chronic otitis media should be referred to their GP with advice on keeping their ears dry. Water precautions are also advised for patients with otitis externa and acetic acid spray may be useful in mild cases.

A summary of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines for the management of these conditions is shown in the Figure.

Figure: A summary of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s guidelines for the management of conditions presenting as a discharging ear

Source: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence[6],[7],[8]

Earache

Ear pain is a common complaint. For example, acute otitis media affects around 75% of children before the age of five years[9]

. It may cause the child to:

- Tug or pull at their ear(s);

- Be irritable and cry;

- Have disturbed sleep.

Most earaches in young children are caused by an acute ear infection, but not all ear pain originates in the ear. It can occur owing to toothache (teething or dental abscesses) or on swallowing in patients with a sore throat, tonsillitis or quinsy (peritonsillar abscess). Rarely, earache can be a sign of a more serious condition in adults, including cancers of the head and neck, such as tonsillar or tongue-based cancers[4]

.

If ear pain occurs alongside hearing loss in children, the cause could be ‘glue ear’ (a significant wax build-up and perforated eardrums).

Ear pain can also occur owing to the presence of a foreign body in the ear.

Management

Pharmacists can advise the use of over-the-counter pain relief, including paracetamol and ibuprofen, and the application of heat to older children and adults[10]

.

Referral to the GP, and possibly to an ENT specialist, is advised if there is a foreign body in the ear. Ear drops should not be used to try to ‘wash out’ vegetative foreign bodies, such as food, since these can swell up and cause irritation or infection. Instead, these patients should be referred to the ENT department emergency clinic.

Dizziness, vertigo and imbalance

There are many causes of dizziness, including:

- Cardiovascular (e.g. irregular heartbeat or fall in blood pressure on standing);

- Neurological (e.g. migraines);

- Diabetes;

- Iron-deficiency anaemia;

- Side effects of medicines;

- Alcohol[11]

.

Stress and anxiety can cause hyperventilation syndrome, whereby over-breathing reduces carbon dioxide levels, which affects the free calcium levels in the body resulting in “dizziness”.

Vertigo is defined as an illusion of movement and can be indicative of an inner ear problem. It may be associated with feeling off-balance (such as with sea-sickness), a change in hearing, tinnitus, nausea and vomiting[12]

.

One of the most common vestibular causes of vertigo is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) which can occur following a head injury, secondary to other vestibular conditions including vestibular neuronitis and Ménière’s disease, or it can happen spontaneously[13]

. In this condition, debris — usually in the posterior semi-circular canal — moves when the head is in certain positions, which induces the symptoms of vertigo that can last up to a minute, but typically occurs for only 15–30 seconds[13],[14]

. This is frequently triggered when the patient turns over in bed or looks up or down.

Patients who experience vertigo and who have associated nausea and vomiting that is severe enough for them to require bed rest before gradually mobilising again over days or weeks may have vestibular neuronitis (if they have no associated hearing loss) or labyrinthitis (where there is an associated hearing loss).

Ménière’s disease is often diagnosed incorrectly. Patients with this condition usually have vertigo lasting for hours, but prior to the onset of this vertigo they experience a feeling of pressure, an increase in tinnitus and subsequent hearing loss in the affected ear[15]

. The hearing may improve between ‘attacks’.

Management

Correct management of these symptoms depends on the cause of the dizziness, but the general advice that can be given to patients would be to keep well hydrated and move slower, particularly if vertigo is induced by head movement. Patients with BPPV can be treated by trained professionals using a particle repositioning manoeuvre such as the ‘Epley manoeuvre’[16]

.

The pharmacy team should advise patients to get up slowly from lying to sitting, then sitting to standing, and that they should refrain from driving if these movements induce dizziness. Should an ‘attack’ come on when driving, they should be advised to safely pull over to the side of the road. Patients with a diagnosis of Ménière’s disease should inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency[17]

.

They should also be advised to follow a low-salt, low-caffeine and low-alcohol diet[18]

. When patients are in the acute phase and have symptoms of vertigo with nausea or vomiting, a vestibular sedative, such as prochlorperazine, may be useful. They should not be used long-term, since this can prolong the time and extent of recovery from vestibular neuronitis and labyrinthitis.

Those patients who have a history of migraines and who prefer to lie down in a dark room after a dizzy attack may have migrainous vertigo. These patients could benefit from taking antimigraine medicines. The reduction in vertiginous episodes with antimigraine prophylactic medicine is useful to confirm this diagnosis.

Referral

If the patient has persistent or recurrent symptoms; hearing loss; tinnitus; double-vision or blurred vision; or numbness or weakness in the face, arms or legs, they should be referred to their GP.

For information on hearing loss, tinnitus and the role of the pharmacist see Managing common ear problems: hearing loss and tinnitus

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to acknowledge the advice from Shahid Chowdhury and Nirali Sisodia, pharmacists at Kettering General Hospital, Northamptonshire

References

[1] Hannaford PC, Simpson JA, Bisset AF et al. The prevalence of ear, nose and throat problems in the community: results from a national cross-sectional postal survey in Scotland. Fam Pract 2005;22(3):227–233. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmi004

[2] Finnikin S & Mitchell-Innes A. Recurrent otalgia in adults. BMJ 2016;354:i3917

[3] Kaur R, Morris M & Pichichero ME. Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Paediatrics 2017;140(3):e20170181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0181

[4] NHS. Overview: perforated eardrum. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/perforated-eardrum/ (accessed November 2019)

[5] NHS. Cholesteatoma. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cholesteatoma/ (accessed November 2019)

[6] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Otitis media — acute. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/otitis-media-acute (accessed November 2019)

[7] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Otitis media — chronic suppurative. 2017. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/otitis-media-chronic-suppurative (accessed November 2019)

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Otitis externa. 2018. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/otitis-externa (accessed November 2019)

[9] Klein JO. Otitis media. Clin Infect Dis 1994;19(5):823–833. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.5.823

[10] NHS. Earache. 2019 Available at: www.nhs.uk/conditions/earache/ (accessed November 2019)

[11] NHS. Dizziness. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/dizziness/ (accessed November 2019)

[12] Ménière’s Society. Symptoms and conditions. 2013. Available at: https://www.menieres.org.uk/information-and-support/symptoms-and-conditions (accessed November 2019)

[13] Riga M, Bibas A, Xenellis J & Korres S. Inner ear disease and benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a critical review of incidence, clinical characteristics, and management. Int J Otolaryngol 2011;2011:709469. doi: 10.1155/2011/709469

[14] Ménière’s Society. BPPV. 2013. Available at: http://www.menieres.org.uk/information-and-support/symptoms-and-conditions/bppv (accessed November 2019)

[15] Ménière’s Society. Ménière’s disease. 2013. Available at: https://www.menieres.org.uk/information-and-support/symptoms-and-conditions/menieres-disease (accessed November 2019)

[16] Hilton MP & Pinder DK. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;12: CD003162. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003162.pub3

[17] Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency. Dizziness or vertigo and driving. 2012. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/dizziness-and-driving (accessed November 2019)

[18] NHS. Ménière’s disease. 2017. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/menieres-disease (accessed November 2019)