Realimage / Alamy

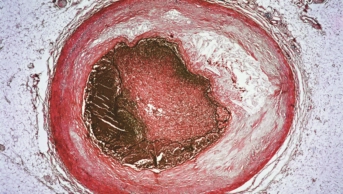

Statins could reduce aggression in men but increase aggression in postmenopausal women, according to research at the University of California, San Diego.

Reductions in aggression were most marked in younger men and men with low baseline aggression. Increases in aggression seen in postmenopausal women were also most notable in those with low baseline aggression. Women and men with lower baseline aggression might have been less influenced by other sources of fluctuation in aggression, making it easier to spot changes related to statin use, suggests Beatrice Golomb, professor of medicine at the UCSD department of medicine, who led the research group.

“The same drug, acting on the same outcome, can produce effects that not only differ in magnitude but can be opposite in direction, in different people,” says Golomb, whose findings were published in PLOS ONE

[1]

on 1 July 2015. “This has been shown for many drugs, not just statins, and evidence supports that this is the case for statins for many outcomes, not just aggression.” Similar bidirectional effects of statins, prescribed to reduce cholesterol, have been reported elsewhere for blood sugar levels, proteinuria, cancer and possibly cognition.

If lower aggression is seen as favourable, the pattern recorded by Golomb’s team reflects previous observations that older age and female sex are associated with less favourable statin effects for several outcomes (including all-cause mortality).

“We speculate that antioxidant-prooxidant duality of statin effects, and effects on cell energy balance, may play a role here, as has been postulated for other outcomes,” suggests Golomb.

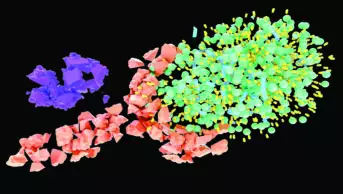

The study is the first randomised clinical trial to look at statin effects on aggression. More than a thousand adults (692 men and 324 postmenopausal women) were randomly assigned to either a placebo or one of two statins; simvastatin 20mg or pravastatin 40mg for six months. Aggression was assessed using the Overt-Aggression-Scale-Modified–Aggression-Subscale (OASMa), which records behavioural aggression (and level of severity of that aggression) over the previous week, including verbal assaults, assaults against objects, assaults against others and assaults against self.

“Though some may suppose that [changes in behaviour] arise from a mystical something ‘intrinsic’ to the person over which biology and chemistry have no dominion, in fact a range of drugs and exposures are reported to influence personality and behaviour,” says Golomb.

The results of the trial largely support what has been suggested elsewhere in the literature. Golomb’s team found that statins reduced testosterone levels in men. However, this was not thought to be sufficient to explain the observed reductions in aggression. Men who took the statin simvastatin experienced reduced testosterone levels but also a rise in sleep problems, which was associated with increased aggression. Two men who experienced the most difficulty sleeping when taking simvastatin showed more aggression as a result of treatment.

There was no significant relationship recorded between testosterone levels or sleep change and aggression levels in women.

Physicians and patients need to be alert to any unexplained change following treatment with statins. If the change is unfavourable, Golomb recommends a break from taking the drug for a couple of months.

“Considering outcomes that objectively and equitably weigh serious benefit against serious risk, like all-cause mortality or all-cause serious morbidity (which tend to track together), there are definitely groups of currently treated individuals in whom evidence does not clearly support treatment [with statins],” says Golomb. “Findings here for aggression parallel findings for some other outcomes, in that younger age and male sex may be linked more favourably to some outcomes, and older age and female sex less favourably.”

The study is a reminder that the full scope of a drug’s harms and benefits might extend beyond the person being treated to those around them, she warns.

James Lake, a board certified psychiatrist and visiting assistant professor of medicine at Center for Integrative Medicine, University of Arizona School of Medicine, has long recognised a link between cholesterol levels, statin use and aggression. He has seen depressed patients with low cholesterol levels secondary to statins who did not respond adequately to antidepressants or evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. He recommends that patients work with their physicians to adjust their statin dose or seek alternative therapies. “It’s good to know that work is taking place in this area,” says Lake, in response to Golomb’s study.