Key points

- In 2017, 81% of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) that responded to the questionnaire had a team to develop and review local antimicrobial guidelines for primary care, which involved secondary care microbiologists and pharmacists.

- Overall, 83% of CCGs that responded reported using the Public Health England (PHE) managing common infections guidance to facilitate the development of their local antimicrobial prescribing guidance. It is thought that this may continue with the combined National Institute for Health and Care Excellence/PHE tabular infection guidance summaries.

- However, 85% of CCGs that responded did not know how often their local guidelines were accessed, or by whom, and did not have a process to monitor or assess implementation or evaluate the impact of guidance on primary care prescribing behaviour.

- Overall, 26% of CCGs that responded reported that they had integrated the antimicrobial guidance into GP clinical systems.

- Medicines management teams (MMTs) requested that guidance for diverticulitis; diabetic foot infections; surgical site infections; giardiasis; pregnant women and neonates with measles should be added to PHE common infections guidance.

- MMTs requested to be informed when national guidance is updated and that changes are highlighted so the MMTs can review local guidance in a timely manner.

Introduction

Many existing antimicrobials are becoming less effective. Bacteria, viruses and fungi are adapting naturally and becoming increasingly resistant to medicines used to treat the infections they cause. Inappropriate use of these valuable medicines has added to the problem. It is estimated that globally only half of antibiotics are used correctly, which can lead to the development of antibiotic resistance[1]

. In the EU, 25,000 deaths per annum are attributed to antibiotic resistance and extra healthcare costs and lost productivity amount to at least €1.5bn[1],[2]

. Therefore, it is a challenge to find the correct balance between prescribing antimicrobials when they are needed and reducing use when they are not.

While concerns are often centred around potential patient harm if antimicrobials are not prescribed, it is agreed that awareness about the association between antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and antimicrobial prescribing needs to improve[3]

.

The ‘UK five-year antimicrobial resistance strategy 2013–2018’ set out actions to address the important challenges to AMR, with the overarching goal to slow its development and spread. It focused activities around three strategic aims: improve the knowledge and understanding of AMR; conserve and steward the effectiveness of existing treatments; and stimulate the development of new antibiotics, diagnostics and therapies[4]

.

In 2015, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) advised that local medicines management teams (MMTs) commissioning primary care services in England should:

- Establish antimicrobial stewardship (AMS) teams, with core members including an antimicrobial pharmacist and a medical microbiologist;

- Update and implement local antimicrobial guidelines in line with national guidance and informed by local prescribing data and resistance patterns;

- Raise awareness of current local guidelines on antimicrobial prescribing among all prescribers, providing updates if the guidelines change[5],[6],[7],[8]

.

Antimicrobial guidance should be used to inform appropriate, evidence-based treatment for common infections presenting within primary care, such as infections of the upper respiratory tract, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract and genital tract[9]

. Evidence shows that when guidance is provided, a more conscientious use of antibiotics is observed[10]

.

Since 1999, Public Health England (PHE) has produced guidance for managing common infections, recommending local modification to account for local choice, antibiotic susceptibility and resistance patterns[11]

. At the time of this study, PHE’s managing common infections guidance consisted of a five-page summary that could be printed for quick reference, as well as a full rationale for the recommendations, which could be referred to by trainees, trainers, medicines management prescribing advisers or primary care prescribers if more detail was required. The guidance was freely accessible through the Royal College of General Practitioners TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) website[12]

.

Other infection guidance is available, including NICE, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) and clinical knowledge summaries (CKS)[13],[14],[15]

. At the time of this study, NICE had published guidance for the treatment of respiratory tract infections (RTIs); acute uncomplicated urinary tract infections (UTIs); community-acquired pneumonia; Helicobacter pylori; and fevers in children aged under five years[16],[17],[18],[19],[20]

. From 2017–2020, NICE has been commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care to produce guidance on the management of common infection syndromes for primary and secondary care[13],[21]

.

Although MMTs within clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) or commissioning support units (CSUs) develop and implement prescribing guidelines locally for use by healthcare professionals in primary care, there has been no recent comprehensive process evaluation of how guidelines for the management of infections in primary care are developed and implemented.

Aim

To determine how local MMTs across England develop and implement prescribing guidance for the management of common infections, including an audit of guideline effectiveness. This is part of a large questionnaire to identify CCG AMS activity. The findings will be used by NHS policymakers and organisations, such as NICE, PHE, Health Education England and the royal colleges, to identify opportunities for improvement and to optimise the management of infections in primary care in England.

Methodology

Ethical consideration

This study was registered with the PHE Research Support and Governance Office and approved by PHE Research Ethics and Governance Group and Health Research Association. Interview and questionnaire responses were anonymised before analysis.

Phase 1: semi-structured interviews

From October to December 2016, in-depth qualitative interviews exploring AMS implementation activities were undertaken, with AMS leads from MMTs representing a range of the 209 CCGs in England. The remit of an MMT is to promote and facilitate safe and effective prescribing through improving quality and reducing risk. A single MMT may be responsible for one or more CCGs. For the purpose of this study, the views of the named AMS lead were taken to represent the views of the MMT.

CCG selection

The 209 CCGs were stratified into quintiles based on their 12-month overall antimicrobial prescribing rate in March 2016 (antibacterial items per specific therapeutic group age–sex related prescribing unit) and randomised using a random number generator[22]

. They were then invited to participate in an interview by email. Non-responders were followed up by telephone. Up to three CCGs from each quintile were interviewed.

Interviewee selection

The heads of medicines management for all 209 CCGs were asked to nominate which MMT member responded to the interview and/or questionnaire, which allowed personalised contact with the named AMS lead.

Between October and December 2016, interviews were conducted over the phone, at a time convenient to the participant, by an experienced qualitative researcher (RA), who was not involved in the development of the PHE managing common infections guidance.

Interview question development

The interviews followed a semi-structured schedule. Questions were developed using the Theoretical Domain Framework to explore all behavioural determinants and AMS activities from the perspective of the lead for AMS within each MMT[23]

.

Analysis

Verbatim transcripts of the qualitative interviews were exported to NVivo (QSR International) and thematically analysed, inductively by RA. In total, 10% of the transcripts were double-coded and the main themes were discussed and validated with the wider research group.

Phase 2: online/telephone questionnaire

Questionnaire development

Findings from the semi-structured interviews were used by the multidisciplinary research team (i.e. consultant medical microbiologist, pharmacists, national AMR leads, statistician and researchers) to develop a broad questionnaire to explore CCG implementation of national AMS initiatives. For example, the participants from phase 1 reported using PHE summary tables in the development of their guidance; therefore, these modifications were the focus for the questionnaire.

The antimicrobial guidance questions covered: antimicrobial committees; frequency of guidance review; how MMTs produce guidance; the format of guidance (e.g. hard copy, electronic); and monitoring use of local guidance. See Supplementary Material 1 for guidance-specific questions from the AMS implementation questionnaire.

Between May and June 2017, eight CCGs who had previously won antibiotic guardian awards were purposefully selected to pilot the questionnaire. Results from the pilot were included in the final analysis as few changes were made to the questionnaire.

Implementation

Between May and September 2017, AMS leads within the MMTs of all 209 CCGs in England were invited via email to complete the AMS implementation questionnaire, either electronically on SelectSurvey or via facilitated telephone completion[24]

.

Participants were given the opportunity to leave free-text comments on each section, allowing respondents to explain their answers. Non- or partial-questionnaire completers were followed up by email and/or phone, a maximum of two times, and reminded to complete[25]

.

Following this, participants were sent a certificate for continuing professional development upon completion, and all participating CCGs were entered into a draw to win either a projector to use in their CCG/CSU or printing costs to the value of £300 for campaign materials around AMS in primary care.

Analysis

Questionnaire data were exported to Microsoft Office Excel, anonymised and descriptively analysed. The free-text answers were exported to NVivo and thematically analysed, inductively, by two researchers (RA with CMcN or DL depending on the topic) to search for common themes.

Results

Respondent demographics

Phase 1

In-depth qualitative interviews were held with 11 MMT AMS leads. Interviews lasted 39–71 minutes.

Phase 2

MMTs representing 187/209 (89%) CCGs responded to the questionnaire. The main reasons for non- or part-completion were lack of time or being new to the role.

Overall, 153/187 (82%) questionnaire respondents reported that their MMT was situated within the CCG; 23/187 (12%) were situated in the CSU; and 11/187 (6%) reported “other”, including outsourcing to a private provider, and a combination of both CCG and CSU employment within the MMT.

In the questionnaire, 146/181 (81%) reported having an antimicrobial committee or equivalent process that develops and reviews local antimicrobial guidelines for primary care. A total of 6/187 CCGs left this answer field blank.

The majority of respondents reported that, while they were the MMT lead for AMS, this responsibility was one of many within their role, with 144/175 (82%) respondents reporting spending only 0.1 whole-time equivalent on AMS activities.

- “The AMS role is only one role within a wide remit, with no specific dedicated time allocated per month.” (CCG-29 – questionnaire)

- “Antimicrobial stewardship forms part of my wider remit for safe and cost-effective use of medicines.” (CSU-2 – questionnaire)

AMS leads representing 85 CCGs reported that developing and implementing their local primary care guidance was a vital part of their AMS role.

- “Actively manage the need, appropriateness, development and approval of antimicrobial prescribing guidelines for use in primary care. Ensure primary care prescribing guidance is reviewed and updated in a timely manner. Develop implementation plans for the guidance to raise knowledge and awareness ensuring appropriate use across organisations.” (CCG-47 — questionnaire)

There was only one response from each CCG. A breakdown of responses to each question is provided in Supplementary Material 2.

How national antimicrobial prescribing guidance on managing common infections is adopted and adapted by medicines management teams

Phase 1

All 11 participants reported that they had input from secondary care (e.g. a microbiologist and hospital pharmacist) when developing the primary care infection guidance in their MMT.

- “Our primary care antimicrobial guidelines were developed with secondary care and they’ve always worked closely with us to enable up-to-date guidelines to be produced within primary care.” (1RA9 — qualitative interview)

- “We are involved with secondary care because we’ve got the area prescribing committee which is joint, and the joint formulary group. So any update with the antimicrobial guidelines is done in conjunction with secondary care and microbiology, and then comes up and is approved through the area prescribing committee.” (2RA5 — qualitative interview)

The majority of AMS leads interviewed reported that their local guidance was adapted from the PHE summary tables. The PHE guidance was mainly reported as being clear and easy to adapt locally, but the ambiguity of wording was reported by some.

- “It’s based on PHE guidance, but it’s localised because of local sensitivities and local microbiology advice. It’s by no means massively out with national, it’s just it has to be localised because of what goes on in the area.” (5RA7 — qualitative interview)

- “We use the short one for locally, but obviously the massive one’s got all the references and things in. So if we have local queries then we go back to that, but then we make sure that what we send out to the GPs is short and sharp. But we don’t change a huge amount. We add a few infections in which locally we find will be useful from having done previous audits.” (3RA8 — qualitative interview)

- “I think they’re fairly straightforward, actually. The way it’s laid out is fairly simple. I think they’re fairly straightforward to understand.” (2RA5 — qualitative interview)

- “Some aspects can be a little bit ambiguous, which I think is one of the things that we get quite often questions about and feedback from our practitioners.” (2RA6 — qualitative interview)

Phase 2

MMTs representing 187/209 CCGs (87%) completed part or all the antimicrobial guidance section.

What antimicrobial guidelines do you promote for your primary care clinicians to use?

A total of 7/187 (4%) CCGs left this answer field blank. Overall, 166/180 (92%) of the remaining respondents reported promoting the use of the 2017 PHE managing common infections guidance to their primary care practitioners. No MMT reported using NICE or SIGN guidance within local prescribing guideline development. However, four respondents reported using CKS to develop their local guidance, which is in line with the pre-questionnaire qualitative phase findings (see Supplementary Material 2).

Whereas, in a free-text box in another section, MMTs representing three CCGs reported promoting relevant NICE guidance.

How frequently are your local primary care antimicrobial guidelines reviewed?

A total of 9/187 (5%) CCGs left this answer field blank, with 178 CCGs completing the question. MMTs reported that their local primary care antimicrobial guidelines were reviewed: every three years (16/178 [9%]); every two years (60/178 [34%]); annually (34/178 [19%]). A total of 33/178 CCGs (19%) reported that their local primary care antimicrobial guidelines were currently being updated. Free-text responses to “other” included: “whenever there is an update to the PHE managing common infections guidance” or “when the need arises”.

When last updated, what changes did the development group make to the PHE managing common infections guidance in the development of your local guidance?

Of the 187 CCG respondents, 7/187 (4%) left this answer blank. Most respondents (149/180 [83%]) produced their guidance by modifying or localising the 2017 PHE managing common infections guidance. Of the 149 CCG respondents, 6/149 left this answer field blank. Of these, 85/143 (59%) respondents reported modifying some of the clinical content by adding, removing or modifying sections or conditions.

Of those that reported the changes they had made, 54/143 (38%) respondents added extra conditions/sections that were absent from the national guidance, including diverticulitis, diabetic foot infections, surgical site infections, giardiasis, and penicillin allergy. When asked about other significant clinical areas that should be included in national guidance, participants also requested national guidance on measles in pregnant women and neonates.

Diagnostic advice was modified by 50/143 (35%) respondents; and 14/143 (10%) respondents removed conditions/sections, but there were no sections/conditions removed that were common to all.

Over the past two years (2015–2017), in which format has the primary care antimicrobial prescribing guidance been presented to primary care practitioners?

The questionnaire asked how MMTs’ antimicrobial prescribing guidelines were published and distributed within the local primary care setting. Of the 187 CCG respondents, 15 (8%) left this answer blank. For those who answered, most (148/172 [86%]) reported using more than one publication format. Digital publication of guidance was favoured by 154/172 (90%) CCGs, and some reported that this was owing to financial restrictions. Digital promotion included via the CCG’s website (112/172 [65%]) and/or local intranet (83/172 [48%]); 44/172 (26%) reported that they had integrated the antimicrobial guidance into GP clinical systems, such as EMIS Web (EMIS Health) and SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership [TPP]). Almost a quarter (42/172 [24%]) of CCGs published guidelines within an app for use by smartphone or computer. Less than half (74/172 [43%]) provided paper copies of their management of infections guidance. See Supplementary Material 2 for a full breakdown of responses.

- “We ran out of paper copies as we couldn’t afford to print that many, so we had to promote the other formats.” (CCG-153 — questionnaire)

Since it was last updated, approximately what percentage of primary care practitioners have accessed the primary care antimicrobial guidance you promote?

Of the 187 CCG respondents, 15 (8%) left this answer blank. For those who answered, MMTs representing 146/172 (85%) CCGs responded that they did not know how often guidelines were accessed, or by whom. Of the 26/172 (15%) that reported they had some knowledge of access to local guidelines, eight CCGs reported >90% of primary care practitioners accessed the guidance; 12 reported 75%; 5 reported 50%; and 1 reported 25%. Respondents reported that they acquired knowledge of access to guidelines through feedback from prescribing meetings with GP staff and the number of digital downloads of local antimicrobial guidance. However, it should be noted that some respondents only estimated the use.

Over the past two years (2015–2017), have you promoted back-up/delayed antibiotic prescribing locally?

Of the 187 CCG respondents, 21/187 (11%) left this answer blank. Back-up/delayed prescribing was reported to be promoted locally by 158/166 (95%) of CCGs. In free-text responses, 37 CCGs commented that advice to use delayed/back-up antibiotics was promoted in their guidance. See Supplementary Material 2 for a full breakdown of responses.

These findings from the questionnaire are consistent with the themes from the qualitative interviews.

The usefulness of the national guidance in facilitating the creation of local guidance

Phase 1

During the interviews, usefulness of national guidance in facilitating the development of local guidance was discussed, but explored in more detail in phase 2. Nothing additional was captured in phase 1.

Phase 2

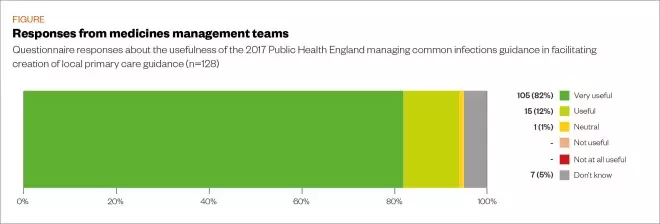

Of the 149 CCG respondents who indicated that they modified/localised guidance based on PHE managing common infections guidance, 21 (14%) did not respond. Of the respondents, 120/128 (94%) indicated it was very useful (n=105) or useful (n=15) (see Figure).

Figure: Reported usefulness of the 2017 Public Health England managing common infections guidance

Source: Source: MAG / The Pharmaceutical Journal

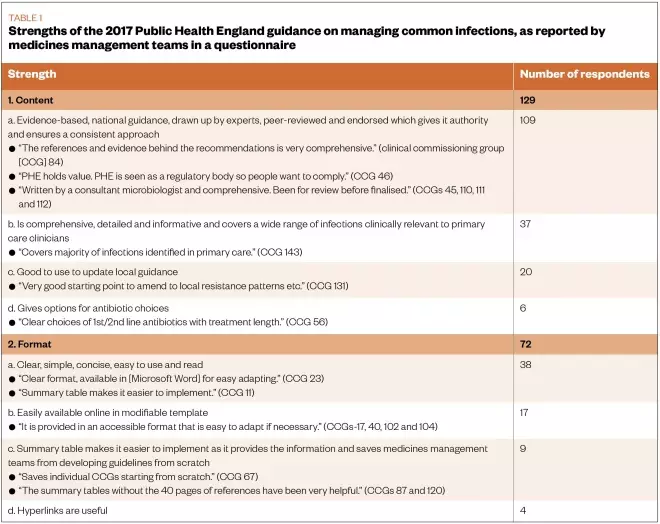

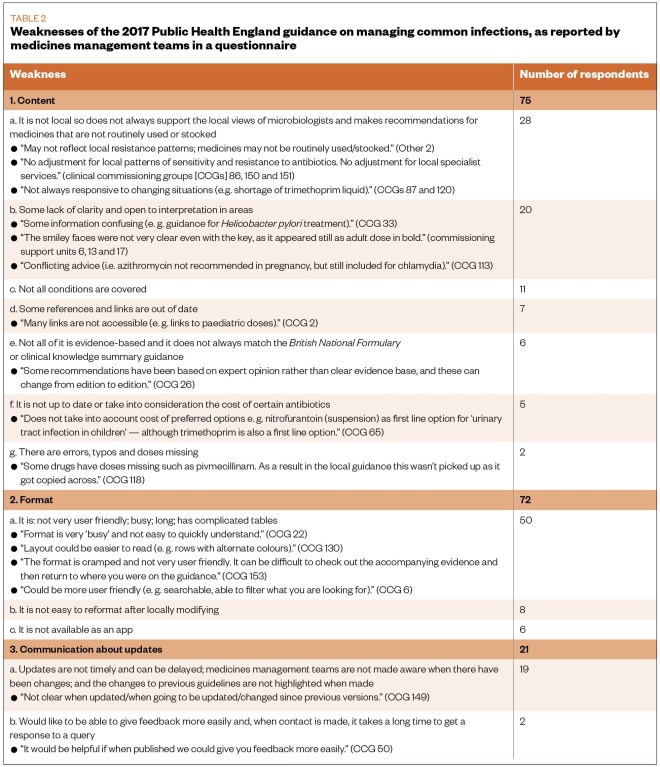

MMTs were asked to state two strengths and two weaknesses of the PHE managing common infections guidance. MMTs representing 129 CCGs reported that the content of the 2017 PHE guidance was its biggest strength, with reasons including: “evidence-based, national guidance, drawn up by experts, peer-reviewed and endorsed, which gives it authority and ensures a consistent approach” (n=109); “comprehensive, detailed and informative, and covers a wide range of infections clinically relevant to primary care” (n=37); and “good to use to update local guidance” (n=20) (see Table 1). Overall, 75 respondents indicated that the content was a weakness, citing reasons such as: “it is not local so occasionally does not support the local views of microbiologists and it makes recommendations for medicines that are not routinely used or stocked” (n=28); and “has some lack of clarity or is open to misinterpretation in areas” (n=20).

Table 1: Strengths of the 2017 Public Health England guidance on managing common infections, as reported by medicines management teams in a questionnaire

Overall, 38 respondents reported that the PHE guidance format was clear, simple, concise and easy to use and read; while 9 stated that the summary table made it easier to implement as it provides the information and saves MMTs from developing guidelines from scratch. Overall, 17 respondents thought that it was easily available online in a modifiable template, whereas 50 respondents reported that it is not very user-friendly; it was busy, long, or had complicated tables. A further eight respondents indicated that it was not easy to reformat after modifying locally.

In total, 19 respondents stated that PHE updates were not timely and can be delayed; MMTs were not made aware when there had been changes; and the changes to guidelines were not highlighted (see Table 2).

Table 2: Weaknesses of the 2017 Public Health England guidance on managing common infections, as reported by medicines management teams in a questionnaire

Discussion

This study indicates that many MMTs used the PHE managing common infections guidance in 2017, and the format and content were reported to be the main strengths of the document. Three-quarters of the MMTs made local modifications, which was encouraged and facilitated by the Microsoft Word format.

Very few MMTs reported using NICE guidance, despite guidance being available at the time of the questionnaire for acute uncomplicated RTIs; UTIs; community-acquired pneumonia; Helicobacter pylori; and fevers in children aged under five years[16],[17],[18],[19],[20]

. The PHE managing common infections guidance summarises the NICE evidence so MMTs do not need to go to the individual NICE guidance, which AMS leads reported being a strength.

In February 2019, to increase use by MMTs and primary care prescribers, NICE and PHE produced a combined summary table of antimicrobial prescribing guidance to continue to facilitate the implementation of the simplified summaries by CCGs[26]

. NICE is also producing visual summaries for users who prefer a pictorial format.

In regard to reducing inappropriate prescribing, local antimicrobial guidance ensures that a consistent approach is used across general practice and minimises the chance of a patient re-consulting with, and obtaining antibiotics from, another clinician within the practice. A self-assessment primary care study reported that 98% (1,385/1,415) of primary care practitioners used antibiotic guidance when considering how to treat common infections; while a separate study reported that 70% (188/269) of primary care practitioners find antimicrobial guidance useful[27],[28]

.

The PHE managing common infections guidance is currently the most widely promoted guidance for use by primary care practitioners and, therefore, it is important that it reflects up-to-date, robust evidence. Furthermore, although local modifications are encouraged, for example tailoring based on local prescribing data and resistance patterns as recommended by the World Health Organization, 23% (41/180) of CCGs signpost directly to PHE managing common infections guidance[29]

. This is possibly owing to the competing demand on time mentioned by many AMS leads (i.e. AMS was only one role within a wider remit, or reviewing and implementing guidance only accounted for a small proportion of activities and responsibilities associated with this role).

In a 2015 questionnaire, only 15/82 (18%) CCGs reported having a guidance development group[30]

. Whereas, this 2017 questionnaire found that 146/181 (81%) MMTs had an antimicrobial committee or process that develops local primary care antimicrobial guidelines, suggesting that implementation of NICE AMS guidance has been effective and may have been facilitated by the Department of Health and Social Care’s five-year strategy[4],[8]

. Nonetheless, MMTs representing 35/181 (19%) CCGs have no antimicrobial committee or equivalent process that develops and reviews local antimicrobial guidelines for primary care. The authors will be feeding back these findings directly to MMTs within development groups to encourage increased compliance with NICE guidance, which indicates that AMS teams should include an antimicrobial pharmacist and a medical microbiologist[8]

.

The importance of developing user-friendly guidance is recognised to inform primary care practitioners of changing recommendations and to enhance patients’ experiences of the primary care system[31],[32]

. MMTs reported reviewing the guidance they promote at least every three years, or whenever there is an update to national guidance. However, participants reported that they were not always alerted to changes. MMTs could be informed through websites such as PrescQIPP, PHE Fingertips, NICE and TARGET, which facilitate dissemination of important messages, such as newsletters and prescribing alerts to members[12],[33],[34],[35],. Furthermore, stakeholders should continue to be consulted during the development stages of future guidance, to ensure that the content is clear throughout and the format is fit for purpose, as these were highlighted by MMTs as weaknesses of the 2017 PHE guidance.

Respondents suggested that guidance should be considered for several conditions not currently covered by PHE. These include: diverticulitis; diabetic foot infections; surgical site infections; giardiasis; penicillin allergy; and measles in pregnant women and neonates[11]

. Although no participants requested more guidance on treating patients with penicillin allergies, fewer than 10% of people believed to be allergic to penicillin are truly allergic, affecting the choice of antibiotic prescribed, the clinical outcomes, increasing healthcare costs and contributing to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria[36],[37]

. Therefore, a more accurate diagnosis of penicillin allergy is essential[38]

. There is also a role for pharmacists to ensure documentation of allergy status is as detailed as possible and to highlight inappropriate allergy labelling to GPs[36]

.

When there is clinical uncertainty about whether a condition is self-limiting or is likely to deteriorate, NICE AMS Quality standards recommend back-up/delayed antimicrobial prescribing, encouraging self-management as a first step, but allowing the patient access to antimicrobials without another appointment if their condition gets worse[39]

. A back-up/delayed antibiotics strategy may be an acceptable compromise in place of immediate prescribing to significantly reduce unnecessary antibiotic use, and thereby reduce antibiotic resistance, while maintaining patient safety and satisfaction levels[40]

.

National guidance recommends considering a “no” or “back-up/delayed” antibiotic strategy for acute self-limiting upper RTIs and mild UTI symptoms[11],[16]

. Back-up/delayed prescribing was reported to be promoted locally by 158/166 (95%) of CCGs, yet implementation and use in everyday practice is unknown. Such prescribing should continue to be recommended in localised guidelines. Future research should explore methods for best implementation of guidance, such as incorporating into AMS education and training for the primary care practitioner, and auditing of antibiotic use against guidance using read-code searches[10]

. Read codes are numerical and alphabetical codes used by GP staff to describe a patient’s symptoms, signs and diagnosis. The codes allow the clinician to record details quickly, and to search systematically for patients with specific codes.

MMTs reported actively promoting their local antimicrobial prescribing guidance; however, AMS leads representing 146/172 (85%) of CCGs did not know how many primary care practitioners had accessed the primary care antimicrobial prescribing guidance promoted locally, since it was last updated. Owing to the wide variety of methods MMTs use to promote their local guidance to primary care practitioners, there is a gap in the mechanism to monitor use and uptake. This questions whether primary care practitioners are using the latest version of local guidance. However, with digital and technological advances, use could be monitored via website downloads or by inclusion within existing audits of clinical systems. Interactive digital guidance was ranked as the top upgrade option by stakeholders in north-west England[41]

.

Wide variation in antibiotic prescribing data at both CCG and GP level suggests that guidelines are not consistently adopted by primary care prescribers[42]

. While this study suggests that there are good processes for local guideline development, supported by national PHE managing common infections guidance, there is clearly less evidence of robust systems to evaluate the effectiveness of local implementation. The employment of additional AMS staff within MMTs, to allow individuals to dedicate more time to AMS, could facilitate better evaluation of effectiveness in optimising antimicrobial prescribing, including monitoring use and assessing the impact of guidelines. This includes assessing the best methods for communicating messages with primary care practitioners and the preferred format of primary care antimicrobial guidance, to optimise implementation and adherence.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is the high response rate, meaning that the results could be representative of the overall development and implementation of guidance by MMTs across England.

Although the questionnaire explored means of guidance provision, such as hard copy versus digital provision, it did not explore to whom the MMTs promote their local primary care antimicrobial guidance. This would be interesting to explore in the future, especially as NHS England is looking to fund more pharmacists in GP practices, and the role of community pharmacists in AMS (e.g. checking antibiotic prescriptions against local guidance) is known to be under-utilised[43],[44]

.

This study was completed before the joint NICE and PHE managing common infections guidance was produced. As this questionnaire was informed by the qualitative phase, in which MMTs did not report using NICE guidance in the development of local infection guidance, there was not a tick-box option for which guidance local MMTs promote or use to develop their local guidance. Participants were given a free-text comment box for “other guidance” in the questionnaire, and NICE guidance was not reportedly used to develop their local guidance, but was mentioned by MMTs representing three CCGs in another section of the questionnaire about “other resources”.

Conclusion

In 2017, the majority of MMTs reported that their local primary care antimicrobial guidance was developed and reviewed based on the PHE managing common infections guidance. In free-text responses and qualitative interviews, respondents indicated that they liked that all common infections guidance were in one document and, therefore, this format should continue. Based on responses, it is recommended that MMTs are informed when national guidance is updated, and changes highlighted, so that the MMTs can review their local guidance in a timely manner. The impact of local antimicrobial guidance needs evaluation; a fifth of CCGs do not have an antimicrobial committee or equivalent process that develops and reviews local antimicrobial guidelines for primary care and may find such a committee useful.

Financial and conflict of interest disclosure

Cliodna A M McNulty, Donna M Lecky, Rosalie Allison are employed by Public Health England (PHE) and work on the TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) programme. Cliodna A M McNulty is the lead for development of the PHE managing common infections guidance. Diane Ashiru-Oredope is the pharmacist lead for antimicrobial resistance at PHE. Rosalie Allison conducted the interviews and analysis and had not been involved in guidance development.

The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organisation or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript. No writing assistance was used in the production of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all antimicrobial resistance/antimicrobial stewardship leads within medicines management teams for participating in our qualitative interviews and/or completing the in-depth questionnaire, and the wider TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly, Guidance, Education, Tools) team for admin support to ascertain the high response rate to the questionnaire.

Author contributions

Rebecca Owens wrote the protocol with input from Rosalie Allison and Cliodna A M McNulty; Rosalie Allison developed the questionnaire with input from Cliodna A M McNulty, Elizabeth Beech, Donna M Lecky, Céire Costelloe and Diane Ashiru-Oredope; Rosalie Allison and Céire Costelloe analysed the quantitative data; Rosalie Allison analysed the free-text data with input from Donna M Lecky and Cliodna A M McNulty; Rosalie Allison wrote the final manuscript with input from Donna M Lecky, Elizabeth Beech, Céire Costelloe, Diane Ashiru-Oredope, Rebecca Owens and Cliodna A M McNulty. All authors approved the final manuscript.

References

[1] European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. The bacterial challenge: time to react. 2009. Available at: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/0909_TER_The_Bacterial_Challenge_Time_to_React.pdf (accessed February 2020)

[2] World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 2015. Available at: https://www.who.int/antimicrobial-resistance/publications/global-action-plan/en/ (accessed February 2020)

[3] Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2010;340:c2096. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2096

[4] Department of Health, Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs. UK five year antimicrobial resistance strategy 2013 to 2018. 2013. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-5-year-antimicrobial-resistance-strategy-2013-to-2018 (accessed February 2020)

[5] NHS England – Primary Care Commissioning (Central team). Primary medical care policy and guidance manual (PGM). 2019. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/primary-medical-care-policy-and-guidance-manual-pgm/ (accessed February 2020)

[6] NHS Clinical Commissioners. About CCGs. 2014. Available at: https://www.nhscc.org/ccgs/ (accessed February 2020)

[7] NHS England. Medicines optimisation. 2017. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/medicines/medicines-optimisation (accessed February 2020)

[8] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial stewardship: systems and processes for effective antimicrobial medicine use. NICE guideline [NG15]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng15 (accessed February 2020)

[9] Dhillon H & McNulty C. How can we improve antibiotic prescribing in primary care? Prescriber 2012;23(22):9–10. doi: 10.1002/psb.985

[10] Fernández FG, Detrés J, Torrellas P et al. Comparison of the appropriate use of antibiotics based on clinical guidelines between physicians-in-training versus practicing physicians. Bol Asoc Med P R 2013;105(3):21–24. PMID: 24282916

[11] Public Health England. Management and treatment of common infections: antibiotic guidance for primary care: for consultation and local adaptation. 2017. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-common-infections-guidance-for-primary-care (accessed February 2020)

[12] Public Health England, Royal College of General Practitioners. TARGET Antibiotics Toolkit. 2012. Available at: http://www.rcgp.org.uk/targetantibiotics (accessed February 2020)

[13] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE guidance. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/conditions-and-diseases (accessed February 2020)

[14] Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Current guidelines. 2017. Available at: https://www.sign.ac.uk/our-guidelines.html (accessed February 2020)

[15] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. 2016. Available at: https://cks.nice.org.uk/#?char=A (accessed February 2020)

[16] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Respiratory tract infections (self-limiting): prescribing antibiotics. Clinical guideline [CG69]. 2008. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG69 (accessed February 2020)

[17] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Urinary tract infections in adults. Quality standard [QS90]. 2015. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs90 (accessed February 2020)

[18] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Pneumonia in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG191]. 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG191 (accessed February 2020)

[19] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. Clinical guideline [CG184]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG184/chapter/1-Recommendations#helicobacter-pylori-testing-and-eradication (accessed February 2020)

[20] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial management. Clinical guideline [CG160]. 2013. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg160/resources/fever-in-under-5s-assessment-and-initial-management-pdf-35109685049029 (accessed February 2020)

[21] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Developing NICE guidelines: the manual (PMG20). 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg20/chapter/introduction-and-overview (accessed February 2020)

[22] NHS Business Services Authority (BSA). Information Service Portal (ISP). 2012. Available at: https://www.nhsbsa.nhs.uk/information-services-portal-isp (accessed February 2020)

[23] Cane J, O’Connor D & Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37

[24] Public Health England. SelectSurvey. 2014. Available at: https://surveys.phe.org.uk (accessed February 2020)

[25] Dillman DA, Phelps G, Tortora R et al. Response rate and measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the internet. Social Sci Res 2009;38(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.03.007

[26] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Public Health England. Antimicrobial prescribing guidlines. 2019. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/antimicrobial-prescribing-guidelines (accessed February 2020)

[27] Owens R, Jones LF, Moore M et al. Self-assessment of antimicrobial stewardship in primary care: self-reported practice using the TARGET primary care self-assessment tool. Antibiotics (Basel) 2017;6(3):16. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics6030016

[28] Jones LF, Hawking MKD, Owens R et al. An evaluation of the TARGET (Treat Antibiotics Responsibly; Guidance, Education, Tools) antibiotics toolkit to improve antimicrobial stewardship in primary care – is it fit for purpose? Fam Pract 2017;35(4):461–467. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmx131

[29] Elias C, Moja L, Mertz D et al. Guideline recommendations and antimicrobial resistance: the need for a change. BMJ Open 2017;7(7):e016264. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016264

[30] Ashiru-Oredope D, Budd EL, Bhattacharya A et al. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship interventions recommended by national toolkits in primary and secondary healthcare sectors in England: TARGET and Start Smart Then Focus. J Antimicrob Chemother 2016;71(5):1408–1414. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv492

[31] Alton S & McNulty C. Common infections: when is the right time to prescribe an antimicrobial? 2017. Available at: https://www.guidelinesinpractice.co.uk/infection/common-infections-when-is-the-right-time-to-prescribe-an-antimicrobial/453550.article (accessed February 2020)

[32] Royal College of General Practitioners. Essential knowledge updates: how the Royal College of GPs uses NICE guidance to deliver essential education to 16000 family doctors. 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/sharedlearning/essential-knowledge-updates-how-the-royal-college-of-gps-uses-nice-guidance-to-deliver-essential-education-to-16000-family-doctors (accessed February 2020)

[33] PrescQIPP, NHS Improvement. Antimicrobial Stewardship (AMS) Hub. 2018. Available at: https://www.prescqipp.info/antimicrobial-stewardship/projects/antimicrobial-stewardship (accessed February 2020)

[34] Public Health England. PHE Fingertips: AMR local indicators. 2019. Available at: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/amr-local-indicators (accessed February 2020)

[35] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE newsletters and alerts: subscribe to medicines and prescribing alerts. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/news/nice-newsletters-and-alerts/subscribe-to-medicine-and-prescribing-alerts (accessed February 2020)

[36] Cramp E, Hamilton R, Kerr F et al. Accurately diagnosing antibiotic allergies. Pharm J 2018;301(7915). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2018.20205068

[37] Jethwa S. Penicillin allergy: identification and management. Pharm J 2015;295(7878). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2015.20069170

[38] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Drug allergy: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG183]. 2014. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg183 (accessed February 2020)

[39] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antimicrobial stewardship. Quality standard [QS121]. 2016. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs121 (accessed February 2020)

[40] McNulty C. Ten top tips on antibiotic prescribing. 2011. Available at: http://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical/ten-top-tips-on-antibiotic-prescribing/13049032.article (accessed February 2020)

[41] Cheesbrough J, Reddy S & Cunniffe J. Modes of presentation and utilization of antibiotic guidance-an attitude survey among providers and users in the North West of England. J Infection 2011;63(6):e83. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.04.144

[42] Johnson AP, Ashiru-Oredope D & Beech E. Antibiotic stewardship Initiatives as part of the UK 5-year antimicrobial resistance strategy. Antibiotics 2015;4(4):467–479. doi: 10.3390/antibiotics4040467

[43] Hemsley S. The medicines management team: a sustainable approach to pharmacist and GP collaboration. Pharm J 2017;299(7905). doi: 10.1211/PJ.2017.20203611

[44] Avent ML, Fejzic J & van Driel ML. An underutilised resource for antimicrobial stewardship: a ‘snapshot’ of the community pharmacists’ role in delayed or ‘wait and see’ antibiotic prescribing. Int J Pharm Pract 2018;26(4):373–375. doi: 10.1111/ijpp.12431