This content was published in 2002. We do not recommend that you take any clinical decisions based on this information without first ensuring you have checked the latest guidance.

It has long been established that pharmacists have a central role in promoting rational and cost-effective prescribing. In 1986, the Nuffield Report1 highlighted the importance of pharmaceutical advice. Soon after, it was recognised that capturing this advice in the form of a formulary was probably the most effective way of improving prescribing practice.

The concept of formularies has gained ground over the years and now forms the basic foundation of modern medicines management systems. It is particularly relevant in the current climate where medicines management appears to be at the top of the agenda for nearly all NHS trusts.

Rationale for formularies

Formularies originally started life in hospitals as a collection of commonly prescribed pharmaceutical preparations, produced mainly for reference purposes. As time went on, the hospital formulary was adapted to incorporate the plethora of information on the increasing number and diversity of medicines. However, these new and expensive preparations required ever-increasing funds, and the formulary rapidly turned into a list of restricted medicines.

The modern formulary is much more than just a collection of preparations. It is an excellent source of detailed local prescribing information, incorporating treatment guide-lines and summaries of best practice.

The main reason for developing a formulary is to set standards for best practice.3 This should promote high quality, evidence-based prescribing and reduce variation in the level of treatment provided to patients. A formulary can be used as a tool to rationalise the range of medicines used in standard practice and to prevent the use of ineffective or overly expensive drugs. With a smaller selection of drugs to choose from, prescribing becomes much simpler.

Furthermore, a formulary can assist in controlling drug expenditure and improving accountability through regular audit.

A formulary can also incorporate clear guidance or algorithms on various prescribing and clinical issues, ranging from the use of unlicensed medicines to local shared care policies. The ultimate aim is to inform and support the health care decision-making process.

In London, the formulary and medicines evaluation (FAME) group gives guidance on the development and education of formulary pharmacists (see box).

The FAME manual3

A local formulary service is not only a valuable tool to supplement national work, eg, by NICE, on the evaluation of new medicines, but it is also the accepted standard first-line process for managing prescribing in both primary and secondary care. The local formulary service is therefore a crucial part of the medicines management process because it can provide an immediate medicines evaluation system close to prescribers.

Despite being such a critical service, the induction and training of new staff is often difficult as the use of reference or training documents is limited.

In London, the formulary and medicines evaluation (FAME) group has been meeting for over six years under the chairmanship of Allan Karr, and assists in the development and education of those involved in this important specialty. The group convenes three times a year at study days to debate mutually interesting subjects, as well as being an opportunity for participants to network informally. Recently, support and funding from London trust pharmacy managers was made available to the FAME group in order to develop a reference manual that is intended to be a useful resource. TheFAME manual is a major step towards supporting those individuals who require a greater insight into this critical pharmacy service.At present, the publication is in use by formulary pharmacists working in London and will be available to the NHS on a website later this year. Further information about the FAME group can be obtained by contacting alison.plant@nwlh.nhs.uk.

Details about the FAME manual can be obtained by contacting med.info@nwlh.nhs.uk

Approving new drugs

The process of approving a drug for addition to the hospital formulary consists of several stages. These can be enumerated as follows:

l. Proposal for addition of a new drug to the formulary

2. Production of an evaluated drug summary:

- Finding the evidence

- Evaluating the information

- Writing the report

3. Decision made by the drug and therapeutics committee (DTC), based on evaluated drug summary

4. Implementation of the decision

Proposal for addition of a new drug to the formulary

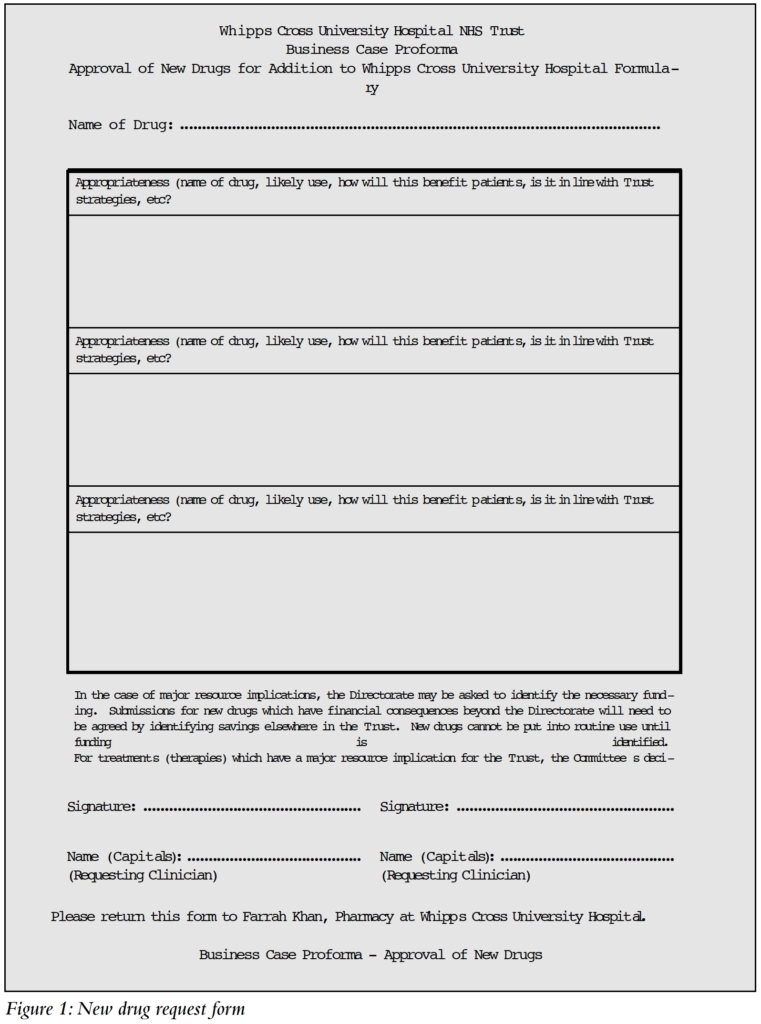

In most hospitals, the proposal for adding a new drug to the formulary will usually be made to the formulary pharmacist (in the capacity of secretary to the DTC). The request is made by a consultant wishing to start using a drug not present in the hospital formulary. The pharmacist will send a new drug request form (Figure 1) to the requesting consultant. The form requires the consultant to provide reasons for the request, and any supporting evidence. An estimate of the patient numbers is also required, together with a simple assessment of the cost implication to the trust. Another equally important component of the form is the identification of funds for the proposed drug:

- Will the new drug be resourced by adjustment within the directorate budget, or will extra funding be required?

- Will it replace an existing formulary item?

The form must then be signed by the requesting consultant and his or her clinical director and submitted to the formulary pharmacist.

Producing an evaluated drug summary

The next phase is the preparation of an unbiased evaluated drug report, based on verifiable information. This is vital for ensuring that the decision to approve or reject the request is based on sound evidence. The importance of evidence-based decision-making has grown rapidly over the past few years. In fact, one of the key aspects of clinical governance is the routine application of evidence-based medicine. This is particularly pertinent to the work of the formulary pharmacist, whose responsibility it is to ensure that all information provided in the formulary conforms, as far as possible, to the best available practice. Since all healthcare interventions are associated with potential risks, it is important to make decisions based on information which can be substantiated. This not only allows the identification of effective interventions, but also highlights those that are ineffective or even harmful.

In order to provide unbiased information, the formulary pharmacist conducts an extensive literature search into the benefits and drawbacks of the drug in question. The sources of information could range from the product licence holder to the internet.3,4 Ideally, the evidence should be from a primary source, such as a journal article or an original news report.

Finding the evidence

Although pharmaceutical companies are eager to market their products, they are also valuable sources of first-hand information, eg, original papers, unpublished data (also known as “data on file”), comparison of drugs within the same class, unusual or rare adverse effects and stability data. Many have now produced formulary packs specifically designed to aid formulary decisions. These will generally include a summary of product characteristics, a product monograph, relevant clinical trial papers and a brief evaluation. Of course, such a selection of clinical trial papers and evaluation tends to provide overall positive evidence about the drug. Some of the larger companies have also developed cost assessment models that can be useful in cost benefit analysis. However, such data must also be viewed with caution, as there may bean element of bias, even if unintended.

With the advent of the United Kingdom Medicines Information (UKMI) website www.ukmi.nhs.uk, locating relevant literature has become much easier. This site contains a wealth of information including evaluated clinical trials and reviews produced by medicines information pharmacists. The area prescribing committee (APC)/DTC database in the members’ section (password protected) enables the formulary pharmacist to find out if a drug has been accepted or rejected by other trusts in the same area. In addition, the website has an excellent links page that allows easy access to other unbiased sites and sources of evaluated information such as the Midland Therapeutic Review and Advisory Committee (MTRAC), the London New DrugsGroup (LNDG), and the North Yorkshire Regional Drug and Therapeutics Centre.5 Many sites are not impartial, and it is up to the individual user to establish the credibility of the information provided. In most cases, a site hosted by an NHS institution, a university or other reputable organisations for example the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), the National Prescribing Centre and the Cochrane Collaboration, can be expected to provide balanced information. Commercial sites are also an excellent source of information, but should be treated with caution.

A literature search would not be complete without a search of abstract databases. Apart from the pharmaceutical companies, these databases are often the best source for identifying original clinical trials. The databases most frequently used by the formulary pharmacist are Medline (contains abstracts from over 3,200 medical journals) and Pharmline (reviews over 90 journals, mainly pharmacy-based). Medline is available free on the internet through search engines such as PubMed (other versions are also available but may require subscription). Pharmline is available on CD-ROM and online but requires subscription. Sound training and a thorough search technique are required to use these databases effectively by means of medical subject headings (MeSH terms). The search can often bring to light research papers offering an alternative view to that presented by a pharmaceutical company, particularly if the research has been conducted independently or by a rival concern.

Evaluating the information collected

There is no guarantee that the evidence collected will be robust or credible. Hence, it must be subjected to a series of criteria to establish its usefulness to the decision making process. This process is known as critical appraisal. Each piece of evidence or clinical trial must be critically appraised to ascertain whether it contains any substance, and not just a series of unjustifiable statements. Critical appraisal is an essential skill for the formulary pharmacist. Many books have been written on the subject, and there are training courses available either as study days or distance learning via the internet. In general, the formulary pharmacist should ask three key questions of each paper:6,7

- Are the results of the study valid? (that is, is the methodology unassailable?)

2. What are the results? (that is, how large or precise is the treatment effect?)

3. Will the results help to improve patient care?

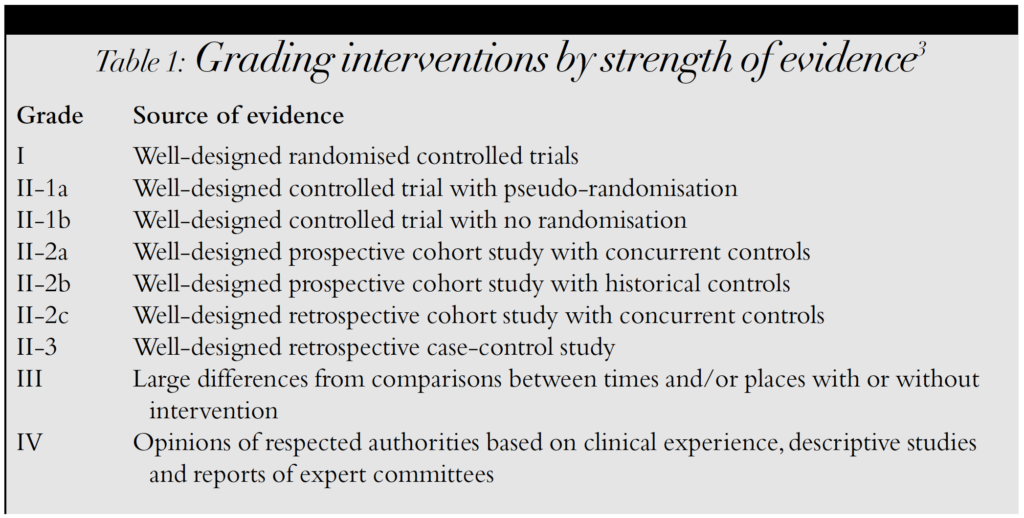

There is an increasing trend to grade clinical interventions according to the strength of evidence portrayed in the study. (See Table 1, which is reproduced with permission from the FAME manual.3)

The general consensus is that the most robust (and more applicable) evidence comes from well-designed randomised controlled trials, whereas anecdotal reports based on individual experiences constitute the weakest form of verification. Such a system is particularly useful when reviewing a drug for which a lot of information is available. However, when reviewing newly launched or licensed drugs, there is often not much data available apart from three or four clinical trials sponsored by the pharmaceutical company. In such cases, a critical appraisal of each trial is even more important to ensure that the evidence is based on sound methodology and reliable statistical analysis.

A quick calculation showing the numbers needed to treat (NNT), that is, the number of patients that need to be treated to achieve one positive clinical effect, is a valuable method for assessing the clinical benefit of the intervention.

Writing the report

The appraised evidence must now be compiled into a report for submission to the DTC. The format should be simple and the text easy to read and understand, because most DTC members have limited time to wade through reams of evidence (that is the job of the formulary pharmacist!). Usually, the evaluation should provide a brief introduction to the new drug, within the context of currently avail-able treatments. The introduction is followed by the proposed indication for the drug and the appropriate dose. It is important to recognise that some drugs are licensed for two or more indications. The request could also be for an unlicensed drug, or for a licensed drug to be used for an unlicensed indication. In order to maintain formulary control and limit expenditure, it is usually necessary to specify the indication(s) for which the item is requested.

The next part of the evaluation normally forms the bulk of the report. This is an unbiased representation of all the appraised evidence, and a synopsis of the drug’s safety profile. The information can be presented in the form of a table showing all the relevant clinical trials and their conclusions, or in the form of a report in which appropriate statements are suitably referenced.The cost of the new drug is also compared with current treatments, taking care to compare equivalent therapeutic strengths and doses. This can also incorporate other factors that are likely to affect the overall cost of the intervention, for example, reduced nursing time or increased patient compliance. Costs may vary considerably between primary and secondary care, and since prescribing in secondary care has a considerable impact onGP prescribing, any cost analysis must reflect this. The report concludes with the recommendations of the formulary pharmacist.

The role of the DTC

The drug and therapeutics committee is an influential body within a trust, and is responsible for deciding which new drugs and treatments should be used in the hospital. Its decision has considerable bearing on drug expenditure and the DTC takes its responsibilities seriously.

To ensure that the DTC is free of bias, its membership is taken from the various key areas within the hospital. Some members are also recruited from outside the hospital. The committee chairperson is usually a senior hospital consultant, with the formulary pharmacist acting as secretary. A typical committee of about 20 members will com-prise consultants in medicine, surgery, dermatology, rheumatology, microbiology and paediatrics. Other members include the chief pharmacist, lead nurse practitioners, a senior member of staff from the finance department, GPs, and representatives from the local primary care trust (PCT) and neighbouring hospital trusts.

The DTC has a broad range of functions and responsibilities. The most basic function of the DTC is to make decisions regarding new drugs and therapies, based on evidence of efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness. In some trusts, the DTC will assess the clinical effectiveness of the drug, but will leave the final decision to another tier of decision makers, who will consider whether appropriate funding is available before approving the drug.

The DTC also takes a lead role in implementing change regarding clinical practice, for example, switching from intravenous to oral antibiotics after 48 hours, and treating potassium chloride as a Controlled Drug to prevent errors in administration. All protocols (such as those dealing with unlicensed medicines, nurse prescribing, and discharge prescription writing by pharmacists) must be approved by the DTC before they can be implemented. In addition, the committee takes a keen interest in prescribing issues in the local PCT. Representatives from both primary and secondary care trusts meet regularly to discuss areas of common interest. Furthermore, the DTC is responsible for ensuring that NICE guidelines are put into practice, and that there is a procedure in place for monitoring the progress of each guideline through all stages of implementation.

DTC decision on formulary admission

Once the formulary pharmacist has compiled a report on the requested drug, a decision has to be made by the DTC. The appraised report is sent out with the agenda for the next DTC meeting, giving commit-tee members time to assimilate the information before the meeting. During the DTC meeting, the formulary pharmacist presents the evidence for or against each requested drug. The requesting consultant is also invited to put his or her case in person.The committee will then debate whether or not it is appropriate to accept the drug into the formulary, and under what circumstances or restrictions, if any.

Implementation of the decision

If a drug is approved, then it is left to the formulary pharmacist to add it to the formulary. Generally, the pharmacist will liaise with the pharmacy business manager to ensure that all computer systems within the pharmacy are updated and the correct parameters for ordering and dispensing the newly approved item are set.

If the formulary is on the hospital intranet then it can be amended fairly rapidly.8 If however, as is still the case in most hospitals, the formulary is available only in book form, it is easier to produce an interim update list; this can be incorporated into the new edition when the formulary is republished. All deci-sions are publicised, often through a DTC newsletter produced by the formulary pharmacist in conjunction with the DTC chairman, or through a pharmacy newsletter. In addition to new formulary additions, the newsletter is used to inform trust staff of new protocols and other medicine related issues.

The formulary pharmacist

Formulary pharmacists carry out various roles related to the DTC and management of the formulary.

DTC secretary

The formulary pharmacist is often also the DTC secretary, and the combination of these two roles makes the post of formulary pharmacist quite demanding and one which carries considerable responsibility. It is the duty of the formulary pharmacist to liaise closely with the chairman of the DTC, arrange DTC meetings, produce agendas and minutes, and generally ensure that all committee members are kept abreast of new decisions. DTC meetings are held on a regular basis, although the frequency varies from trust to trust.

Between meetings, the formulary pharmacist is responsible for responding to new drug requests from consultants. This includes the whole process of critical appraisal from research to report writing outlined above.

The formulary pharmacist also has a supporting role within the pharmacy department, providing assistance and back-up to colleagues whenever prescribing issues arise. In addition, any matters of interest raised within pharmacy can be fed back directly to the DTC, for example, a sudden increase in the use of a non-formulary item, or the availability of a cheaper generic version of a patented drug.

Formulary management

The formulary pharmacist’s other significant role is the maintenance and update of the trust formulary. The formulary pharmacist is usually involved at every stage of formulary development, from conception to publication and distribution. Although the work is usually done in conjunction with a consultant, it is nevertheless arduous and challenging. Updating the formulary not only requires the addition of new drugs, but policies and procedures also require revision.This involves liaising with lead clinicians and section heads.

Copies of the relevant sections from the old formulary are sent out systematically to specialist consultants.They are asked to make any amendments as appropriate. In addition, specialist pharmacists are asked for their input. The process of obtaining comments isa fairly lengthy one and involves a considerable amount of correspondence and waiting for responses. It is important to get as many people as possible involved at this stage, so as to engender a general sense of ownership that will assist later in the implementation of the formulary.

After receiving feedback from the various parties, the formulary pharmacist incorporates the amended sections in the new edition.

The layout and design of the formulary is usually left to the pharmacist. Great care is taken to ensure consistency throughout the book and that the format is clear and easy to understand. A draft copy is printed and proofread by a team of pharmacists. Once a final version has been produced, a suitable printing firm is chosen and the formulary sent for printing. Choice of paper, cover and type of binding is limited by the budget allocated. Many trusts and specialist teaching hospitals are able to sell their formularies on a large scale, enabling them to produce glossy documents while keeping their costs to a minimum.

After publication, it is important to ensure that the message of rational prescribing conveyed by the formulary is consistently understood and applied in day-to-day practice. Thus the launch of the new edition is publicised in every way possible, ranging from newsletters to seminars. Rational prescribing is also promoted through prescription monitoring as well as direct liaison with consultants.

Many hospitals have a policy where pharmacists are authorised to substitute any non-formulary item with an equivalent from the hospital formulary. In such cases, formulary control is relatively easy. Other hospitals prefer not to change a patient’s medicines on admission, so as to maintain continuity of treatment. This means that the pharmacy department would have to keep a large variety of non-formulary medicines. To overcome this, such items are obtained on an individual patient basis, sufficient for their stay as inpatients and to take home on being discharged. This has become much simpler with the introduction of one-stop dispensing.

The most challenging aspect of formulary implementation is to get consultants to adhere to prescribing formulary items only.9Once the consultants are on board, it is relatively easy to educate the junior staff.However, this is a constant struggle because, almost as soon as a particular batch of doctors are trained, it is time for them to move on. Fortunately, the formulary pharmacist is able to enlist the support of ward pharmacists and dispensary staff in promoting formulary use. It is important to remain vigilant at all times. If a team of doctors are allowed to prescribe non-formulary items without check, the problem seems to expand rapidly and it becomes extremely difficult to regain adherence to the formulary.

The performance of a formulary and adherence to it needs to be monitored regularly through an audit of non-formulary items. This can be done in a variety of ways and there are various data analysis programs available to assist the formulary pharmacist.The data can highlight problem areas that can then be tackled individually, either by contacting the relevant consultant or through the DTC. However, a degree of flexibility is usually required to allow for unusual or urgent cases. In such circumstances, the chairman of the DTC will give “chairman’s action” authorising the use of a non-formulary item or an unlicensed drug. The aim of monitoring is to ensure that the DTC is aware of all drugs prescribed within the trust.

Skills required

In order to be able to fulfil their roles, formulary pharmacists have to be multiskilled. The basic skills required for the role include the following:

Project management skills

Project management skills are required for managing all aspects of formulary production effectively.Excellent organisational skills are also required.

Time management skills

Time management skills are required in order to be able to work to tight deadlines.

Communication skills

It is essential that the formulary pharmacist should be able to communicate successfully with all levels of staff. Good listening skills, a positive attitude and a positive body language are all involved.

Team-working skills

It also helps if the formulary pharmacist is a competent team player, because there is considerable involvement in subcommittees and working parties in addition to the DTC.

Negotiating and influencing skills

Often, the evidence is not clear-cut and good negotiating skills can prove useful in preventing unnecessary confrontations. It is also a great asset if the formulary pharmacist can persuade consultants that having a formulary is in their interest.

Writing skills

Good writing skills are essen-tial for conveying the right message.

Ethical decision making

Formulary pharmacists are expected to conduct themselves in accordance with the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s Code of Ethics for pharmacists.

In addition to the above, the formulary pharmacist must have a clear understanding of the NHS structure both within the hospital setting and in primary care. It is important to be aware of the lines of accountability and have an idea of how different parts of the NHS are interconnected.

A good grasp of the legal issues surround-ing refusal of treatment to patients in theNHS is useful when making decisions at theDTC meeting. For example, it is not considered appropriate to refuse treatment endorsed by NICE simply on the basis of cost. Although there have been cases where experts in particular fields do not agree with NICE guidance, in the final analysis, evidence-based medicine should prevail.

It is expected that the formulary pharmacist will have some knowledge of the procurement process and the hospital discounting scheme, although this is usually the responsibility of the procurement pharmacist or the pharmacy business manager. In addition, a good clinical knowledge base is required, as well as critical appraisal skills and basic IT skills (to search databases and the internet). General medicines information skills such as knowledge of different information sources, and the ability to develop sound search strategies, are also essential for the accomplished formulary pharmacist.

The future

Medicines management is vital for containing the sudden explosion in drug expenditure caused by the advent of new and expensive medicines.

Since a rigorous application of the formulary is central to any respectable medicines management system, the future for formulary pharmacists looks bright. They are likely to become more influential, particularly with the introduction of electronic prescribing and the intranet-based formulary, in addition to the development joint trust and PCT formularies. These changes will facilitate the implementation of a better medicines management system, reduce expenditure and improve the continuity of care to patients. The formulary pharmacist can indeed have a positive impact on the delivery of health care within the NHS.

References

1.Nuffield Foundation. Pharmacy: a report to the Nuffield Foundation. London: Nuffield Foundation; 1986.

2.Tweedie A. Medicines management and change management — the PSNC pilot trials. Pharm J 2002;268:146.

3.Haria M, Slater A. Formulary and MedicinesEvaluation (FAME) Manual 2002. London:London Regional Pharmacy Services; 2002.

4.Johnson M.Where to start looking for medicines information on the internet. Pharm J 2001;67:167–9.

5.Sources of evaluated information on clinical effectiveness. MeReC Briefing 1998;12:1–8.

6.Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to medical literature. JAMA 1993;270:2598–601.

7.Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to medical literature. JAMA 1994;271:59–63.

8.Tugwell C.Taking pharmacy services to a new level with the intranet. Hosp Pharm 2001;8:158–62.

9.Fitzpatrick RW, Mucklow FC, Fillingham D. A comprehensive system for managing medicines in secondary care. Pharm J 2001;266:585–8.