Shutterstock.com

Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/coronavirus

Mental health services for children and young people were struggling before the COVID-19 pandemic, but data suggest they are now reaching crisis point.

NHS figures, analysed by the Royal College of Psychiatrists and published in April 2021, show that 80,226 more children and young people were referred to mental health services between April 2020 and December 2020, up by 28% on 2019[1].

In addition, the analysis revealed that the number of children and young people needing urgent or emergency crisis care — including assessments to see if someone needs to be sectioned because they or others are at risk of harm — had increased by 18% compared with 2019.

However, this is — to use a cliché — ‘the tip of the iceberg’, in terms of need.

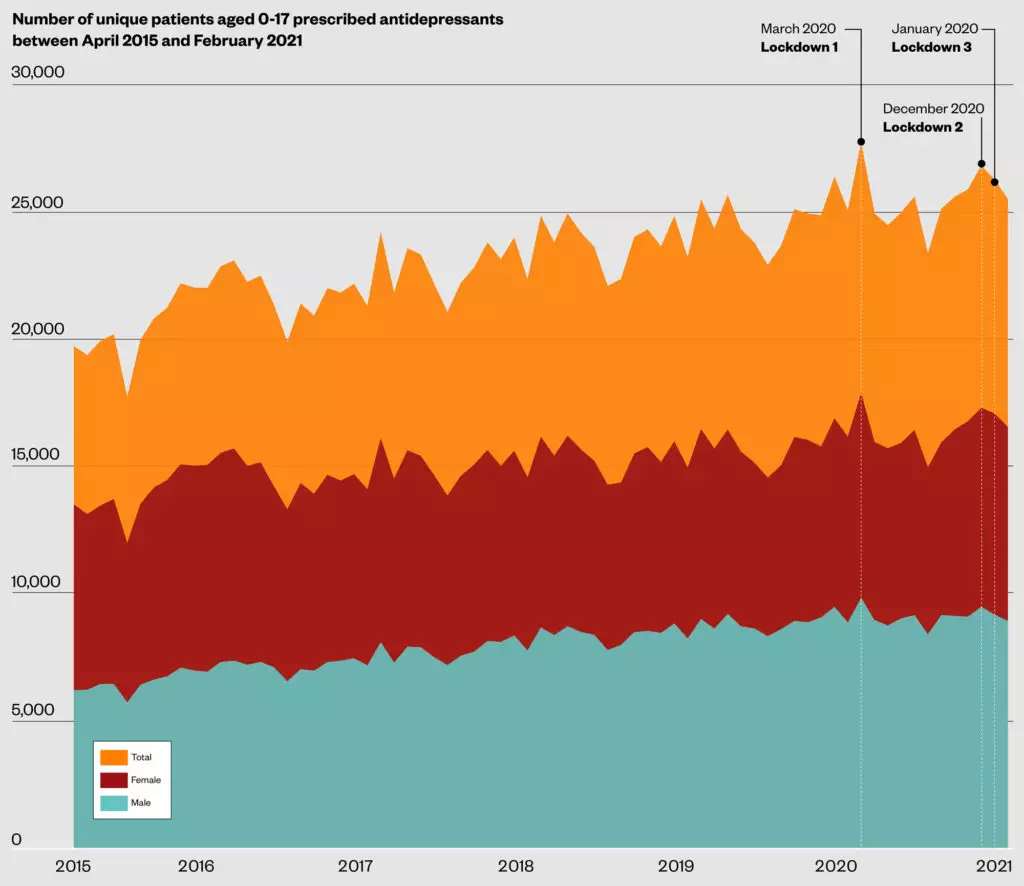

Further data, obtained exclusively by The Pharmaceutical Journal from the NHS Business Services Authority, show a steady increase over the past five years in the number of unique patients in England aged 0-17 years who were prescribed antidepressants, which were then dispensed in primary care settings.

Between April 2015 and April 2020, the number of unique patients prescribed antidepressants increased by 26%, from 19,739 to 24,957.

However, this trend appeared to accelerate during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly during periods of national lockdowns (see Figure)[2].

In March 2020, when the first UK lockdown began, the number of patients prescribed antidepressants reached a peak, with 17,902 females and 9,855 males; the first time the number of females prescribed antidepressants had surpassed 17,000 during the data period. This represented an 8% increase compared with the number of unique females and males who were prescribed antidepressants in March 2019.

Two further peaks of 17,311 and 17,088 antidepressant prescriptions for female patients were seen around the time of the second and third lockdowns, in December 2020 and January 2021, respectively[2].

There [was already] a demand and resource issue in terms of workforce recruitment and retention, and then … the pandemic struck

Bernadka Dubicka , consultant psychiatrist and chair of the Child and Adolescent Faculty at the Royal College of Psychiatrists

“Before the pandemic, we were concerned about childhood mental health problems,” says Bernadka Dubicka, a consultant psychiatrist and chair of the Child and Adolescent Faculty at the Royal College of Psychiatrists.

“There [was already] a demand and resource issue in terms of workforce recruitment and retention, and then of course the pandemic struck and … demand for services was at an all-time high; it was the perfect storm of a number of factors coming together.”

A perfect storm

These factors are varied — and many were there before the pandemic — but the result has been a notable rush in the numbers of young people now seeking help for mental illness in the UK.

Providing evidence to the health and social care committee’s inquiry into children and young people’s mental health services on 23 March 2021, Emma Thomas, chief executive of mental health charity Young Minds, told MPs that 30% of young people with existing mental health problems had lost the support they normally relied on during the pandemic. And, she said, there was now a second group of young people — those who had developed a mental illness during the pandemic.

Survey data published by Young Minds in February 2021 showed that many young people were feeling a sense of frustration, partnered with uncertainty about the future and a loss of hope[3]. Some said that they had started self-harming, having panic attacks or suicidal thoughts, while others expressed growing anxieties about food, eating or weight, missing human contact, or losing motivation to carry out basic tasks or to look after themselves.

The lockdowns and school closures in response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic led to breakdown in routines for many children

Beryl Navti, advanced mental health pharmacist at North East London NHS Foundation Trust

“Young people and their parents or carers are more aware of the signs and symptoms of mental health illness and increase in digital connectivity has meant more contact being made with services, either through self-referral or via GP practices, when needed,” explains Beryl Navti, an advanced mental health pharmacist at North East London NHS Foundation Trust.

“The various lockdowns and school closures in response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic led to breakdown in routines for many children, and from my experience working with a few in this period, increase in feelings of despondency.

“Many parents who ordinarily would have been able to give emotional support to children in their care have found themselves struggling with their own emotional wellbeing as the pandemic has gone on.”

In addition, Navti explains that for young people who used school attendance to get away from difficult situations at home, such as domestic violence, the various lockdowns left them feeling trapped and isolated.

Treatment delayed

The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline for depression in children and young people recommends only selected antidepressants for young people with moderate or severe depression[4]. It also recommends that they be given alongside talking therapies, following assessment by a mental health specialist.

However, with child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) stretched to the limit before the pandemic hit, the wait to access psychological support is getting longer and prescribing of antidepressants for children and young people appears to be on the rise.

“There isn’t much scope to help with psychological work … the wait lists are very, very long, and what that means is, medication becomes the default option,” says Graham Brown, lead children’s and younger people’s mental health pharmacist at Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust.

“If you’ve got a young person crying out for help, and you know that they’re not going to be seen for six months, it’s not ethical to withhold something that might help.”

There isn’t much scope to help with psychological work … the wait lists are very, very long, and … medication becomes the default option

Graham Brown, lead children’s and younger people’s mental health pharmacist at Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust

According to ePACT data collected by Brown, there have been sizeable increases in antidepressant prescribing by CAMHS services. For instance, Sussex CAMHS issued around 400 more antidepressant prescriptions between March 2020 and March 2021 than it did between March 2019 and February 2020 — around a 22% increase.

In addition, Hampshire CAMHS showed a larger increase in antidepressant prescribing, with an extra 750 antidepressant prescriptions issued between March 2020 and March 2021 compared with the same period the previous year; around a 32% increase.

“Certainly within Worthing CAMHS, where I am clinically based, there has been an increase in pressure to prescribe antidepressants, partly due to seeing more patients with such concerns but also there being insufficient resourcing of psychological therapy in this geographical area,” he explains.

Brown provided virtual counselling sessions during the pandemic to maintain contact with his patients. But this was not without its challenges.

“I had probably seven or eight young ladies who just refused to get in front of the camera. And the whole point of an assessment is not, not just to hear them, but it’s to watch them for those non-verbal cues, which are all important,” he explains.

“If somebody won’t get in front of the camera, it makes the assessment process a bit null and void really.”

These issues were partnered with temperamental internet connections and, in some patients, a failure to engage altogether.

“Virtually serves a purpose to a point, but it doesn’t replace face-to-face [contact],” he says.

Navti believes that all young people known to CAMHS should be individually assessed for suitability for using online services.

“In my experience, many young people are given the option of either telephone consultation or to have their cameras off during online video consultation. I feel a lot can be missed by not being able to assess someone’s body language, surroundings, facial expressions and other non-verbal communications,” she says.

A lot can be missed by not being able to assess someone’s body language, surroundings, facial expressions and other non-verbal communications

Beryl Navti, advanced mental health pharmacist at North East London NHS Foundation Trust

Despite the increasing availability of online counselling services, CAMHS continue to be overwhelmed, with children and young people having to wait months — sometimes years — for access to psychological support.

A survey by NHS Providers, published on 25 May 2021, showed that of the 35 mental health trust leaders who responded to the survey, 100% said that the demand their local systems were experiencing for CAMHS had increased either significantly or moderately, compared with six months ago[5].

In addition, 85% of trust leaders said they could not meet demand for eating disorder services and two thirds of trust leaders said they are not able to meet demand for community CAMHS (66%) and inpatient CAMHS (65%).

“We’re cut to the bone,” says Brown.

Antidepressant prescribing

Most parents will initially visit their GP with concerns about their child’s mental health issues. The GP will then refer them to a specialist in child and mental health, if appropriate. However, with waiting times sometimes exceeding six months, antidepressants often end up being the only immediate alternative for GPs[6].

“Antidepressants are often an effective treatment that can help patients manage mental health conditions — but any decision to prescribe will be made in conversation between a GP, the young patient and their family, taking into account their individual circumstances, the benefits and risks of the treatment, and considering alternative treatments, such as CBT [cognitive behavioural therapy] and talking therapies,” explains Martin Marshall, chair of the Royal College of GPs.

“However, access to appropriate, alternative therapies in the community, that many younger patients with mental health conditions find beneficial, is patchy across the country. This needs to be addressed urgently to ensure younger patients can access these treatments quickly, particularly in view of the increased demand for these services due to the pandemic.”

Access to appropriate, alternative therapies in the community … is patchy across the country

Martin Marshall, chair of the Royal College of GPs.

Commenting on the increase in antidepressant prescribing for children and young people during the lockdowns, Navti highlights that antidepressants are prescribed for both depression and anxiety disorders. “If we are saying that levels of anxiety increased among some young people during these periods, it makes sense that there would have been a corresponding increase in prescribed medication,” says Navti.

“In patients already diagnosed with anxiety disorders or depression and prescribed medication, there could have been an increase in demand for repeat prescriptions every time a lockdown was announced, and as community pharmacies remained open, it stands to reason that prescribing costs would reflect these spikes in demand.”

However, Dubicka is concerned about whether those same young people prescribed antidepressants are also able to access psychological therapy.

“We wouldn’t want medication prescribed to be a substitute for psychological therapy, if that was indicated and needed,” she adds.

Moving forward

In May 2021, NHS England announced that around 400 mental health support teams would be “up and running” covering 3,000 schools in England by 2023, offering support to almost three million pupils. A month later, it announced that an extra £40m has been allocated to address the impact of COVID-19 on children and young people’s mental health and enhance services across the country.

School-based support could make a significant difference; research carried out by the University of Exeter and University of Cambridge showed that school-based, one-to-one counselling sessions improved the long-term mental health of primary school-aged children, regardless of whether they had a mental health disorder to start with[7].

The roll out announced by NHS England represents an acceleration of the programme first mooted in the ‘NHS Long Term Plan’, which aims to ensure that, by 2028, 100% of children and young people who need specialist mental health support will be able to access it.

But, Dubicka says, “we’re a long way from that”.

“We don’t really have a blueprint as to how we’ll achieve that either with funding, or the structure and with workforce.”

However, she says, the pandemic has also presented opportunities of ways to do things differently.

We need to find out why prevalence signals were rising even before the pandemic … that suggests [there is] something very wrong going on in our society

BERNADKA DUBICKA , CONSULTANT PSYCHIATRIST AND CHAIR OF THE CHILD & ADOLESCENT FACULTY AT THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF PSYCHIATRISTS

“We’ve seen that with the way we’ve started working digitally in services and there’s lots of scope for that; we know there’s lots of children and young people who maybe wouldn’t want to attend in person so there are lots of opportunities for reaching out.”

However, ultimately Dubicka says it is necessary to address the fundamental issues that were present long before COVID-19 to truly move forward. For example, there has long been a disparity between what is spent on CAMHS, compared with what is spent on adult mental health services — on average, local clinical commissioning group areas spend less than 1% of their overall budget on children’s mental health and 14 times more on adult mental health[8].

“We need to [find out] why prevalence signals were rising even before the pandemic because that suggests [there is] something very wrong going on in our society,” says Dubicka. “Poverty is a huge driver in terms of mental health difficulties and inequalities, and of course we know that that has been made even worse with a pandemic.

“[What] we do know [is] that, the sooner you can provide help for mental health problems, the sooner young people can recover and get on with their lives.”

- 1Country in the grip of a mental health crisis with children worst affect, new analysis finds. Royal College of Psychiatrists. 2021.https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2021/04/08/country-in-the-grip-of-a-mental-health-crisis-with-children-worst-affected-new-analysis-finds (accessed 22 Jun 2021).

- 2Timeline of UK Coronavirus lockdowns. Institute for Government Analysis. 2021.https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/timeline-lockdown-web.pdf (accessed 22 Jun 2021).

- 3Coronavirus: Impact on Young People with Mental Health Needs. Young Minds. 2021.https://youngminds.org.uk/about-us/reports/coronavirus-impact-on-young-people-with-mental-health-needs/ (accessed 22 Jun 2021).

- 4Depression in children and young people: identification and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2019.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng134 (accessed 22 Jun 2021).

- 5Children and young people’s mental health survey. NHS Providers. 2021.https://nhsproviders.org/resource-library/surveys/children-and-young-peoples-mental-health-survey (accessed 22 Jun 2021).

- 6Jack RH, Hollis C, Coupland C, et al. Incidence and prevalence of primary care antidepressant prescribing in children and young people in England, 1998–2017: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003215. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1003215

- 7Finning K, White J, Toth K, et al. Longer-term effects of school-based counselling in UK primary schools. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry Published Online First: 14 May 2021. doi:10.1007/s00787-021-01802-w

- 8Oral evidence: Children and young people’s mental health, HC 1194. Health and Social Care Committee. 2021.https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/1959/html/ (accessed 22 Jun 2021).