Ranjita Dhital

The role of community pharmacists has evolved rapidly since the COVID-19 pandemic, placing them firmly at the top of the list of healthcare professionals accessed most often by the public.

But while their function has progressed, the spaces that pharmacists and their teams work in has, in most cases, not kept up with these changes — an issue that has prompted researchers at University College London (UCL) to consider the role of architecture in community pharmacy and what that might look like in the future.

The ‘Architecture of Pharmacies‘ is a research project created and led by Ranjita Dhital, a pharmacist, artist and lecturer in interdisciplinary health studies at UCL; and Joseph Cook, an anthropologist at UCL, with a focus on architectural design.

As an interdisciplinary arts-based research project, it aims to understand how the space within community pharmacies is experienced by patients and staff. Following initial research: a ‘Systematic review on the effects of the physical and social aspects of community pharmacy spaces on service users and staff’ (see Box), which was published in March 2022 in Perspect Public Health, the researchers have since set out to further discuss how the architecture of pharmacies may affect engagement with current and future services.

Having worked as an addiction specialist pharmacist, a community pharmacist and in public health, Dhital has first-hand experience of how a space can shape a patient’s experience. “I saw patients with a wide range of health and social problems [and] I remember the awkwardness of trying to have private conversations with them whilst not really having any private space,” she says.

Even with the significant developments in the profession we’ve seen over the years, the pharmacy space remains a neglected area

Ranjita Dhital, pharmacist, artist and lecturer in interdisciplinary health studies at University College London

Later involvement in research for an MSc and a PhD exploring alcohol problems and how people could be supported by their pharmacist to reduce their level of drinking led Dhital to think again about the importance of private spaces, where people could sit comfortably and express their health needs without shame or embarrassment.

“Even with the significant developments in the profession we’ve seen over the years, the pharmacy space remains a neglected area,” she says.

“There’s very little guidance and support for pharmacy teams who are looking to optimise their spaces, especially to enable them to care for their patients in ways that fully demonstrate their professional knowledge and expertise. Therefore, through having poor pharmacy spaces, we are not optimising the breadth and depth of learning and training pharmacists and their team possess.” Dhital adds that now is an important time to do this study, as the profession — and pharmacy training — is changing, with graduates set to qualify as independent prescribers from 2026.

To address the lack of guidance, Dhital and her team brought together practitioners in pharmacy and architecture, a health historian, an anthropologist, experts in mental health and a PhD student to scope out multiple perspectives for the project.

Among this team is Darshan Negandhi, a pharmacy trainer and clinical pharmacist at Morden Primary Care Network (PCN), whose work in community pharmacy has given him first-hand insight into how the layout of a pharmacy can significantly affect patient care.

“In essence, the Architecture of Pharmacies study is not just about aesthetics; it’s about reimagining an environment that supports the health and wellbeing of patients through efficient service delivery and safe medication practices,” he says.

“A welcoming and well-organised space can positively influence patients’ perception of the pharmacy, fostering trust and encouraging repeat visits. The space can also be conducive towards the patient’s wellbeing and utilise all the senses to evoke a positive and honest conversation with the pharmacist, especially since we are heading towards a service-centric model.”

Corrinne Burns

Workflow efficiency is another benefit of a considered layout, which Negandhi says can “prevent delays and errors in medication dispensing, leading to improved patient safety and patient experience”.

“Having an effective layout can also facilitate better medication management practices, ensuring that pharmacists and patients have quick and accurate access to medications, and a planogram [a schematic drawing of shelves and products] that takes into account the diversity in physical restrictions and promoting self-care for the patient,” he explains.

Privacy implications

While there is no argument over the importance of privacy for patient consultations, this issue has come further to the fore since the implementation of Pharmacy First at the beginning of 2024, as well as the community pharmacy independent prescribing pathfinder pilots, which will enable pharmacists to prescribe medicines on the NHS.

“As we know, Pharmacy First allows pharmacists to manage certain conditions directly, which necessitates a private environment for safe and confidential patient assessments,” says Negandhi, adding that the independent prescribing pathfinder pilot programme further increases the need for private consultation areas to discuss sensitive health information.

In addition, the recent announcement that pharmacy technicians will be able to supply medication under patient group directions from 26 June 2024 demonstrates what Negandhi calls “a seismic shift” towards a change in the responsibilities of pharmacy teams.

It has to be a welcoming space, but one that also reassures patients that they will be safe and their consultation will be private

Bukky Alli, pharmacy manager and group training lead for the undergraduate foundation programme at Green Light Pharmacy Group

For Bukky Alli — who splits her role at the Green Light Pharmacy Group between managing pharmacies and as the group’s training lead for its undergraduate foundation programme — the pharmacy space is about more than just the building itself.

“The pharmacy serves so many different purposes for staff and patients,” she says. “It’s a place for people to come and be heard, and for staff to work with them to find out how best they can help, which is why architecture is so important.

“It has to be a welcoming space, but one that also reassures patients that they will be safe and their consultation will be private, and where staff can move around freely in order to do their job in the best and safest way.”

Future pharmacies

To this end, Alli says there are some possible changes to pharmacy in the future that architecture needs to consider. “At the moment, pharmacists tend to think practically in terms of storage and general functionality, with a large counter and a consultation room, no matter how small,” she says.

“But going forward, maybe we should flip it so the counter is a very minimal area that maybe just takes payments, whereas for everything else that requires advice, it’s more important to patients to have a safe, private, comfortable consultation space they can go into.”

Catherine Walker, museum officer at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS), highlighted that patients’ feedback about the pharmacy counter in the Architecture of Pharmacies systematic review was that it felt like a barrier to accessing the pharmacy team.

“Reimagining the counter will help the pharmacy team be more visible,” says Walker. “Depending on the height of the counter, the team can be hidden, so lowering it could make the pharmacy more welcoming. However, we must ensure that any redesign continues to prioritise the safety of medicines and pharmacy teams.”

More inclusive pharmacies

When it comes to tackling other barriers to access, Amandeep Doll, head of engagement and professional belonging at the RPS, says in order to make pharmacies more inclusive, there are several areas to focus on.

“It’s important to ensure that the entire pharmacy, including the consultation room, is accessible to everyone, including those using wheelchairs,” says Doll. “While many pharmacies are designed with patient accessibility in mind, staff areas often aren’t.”

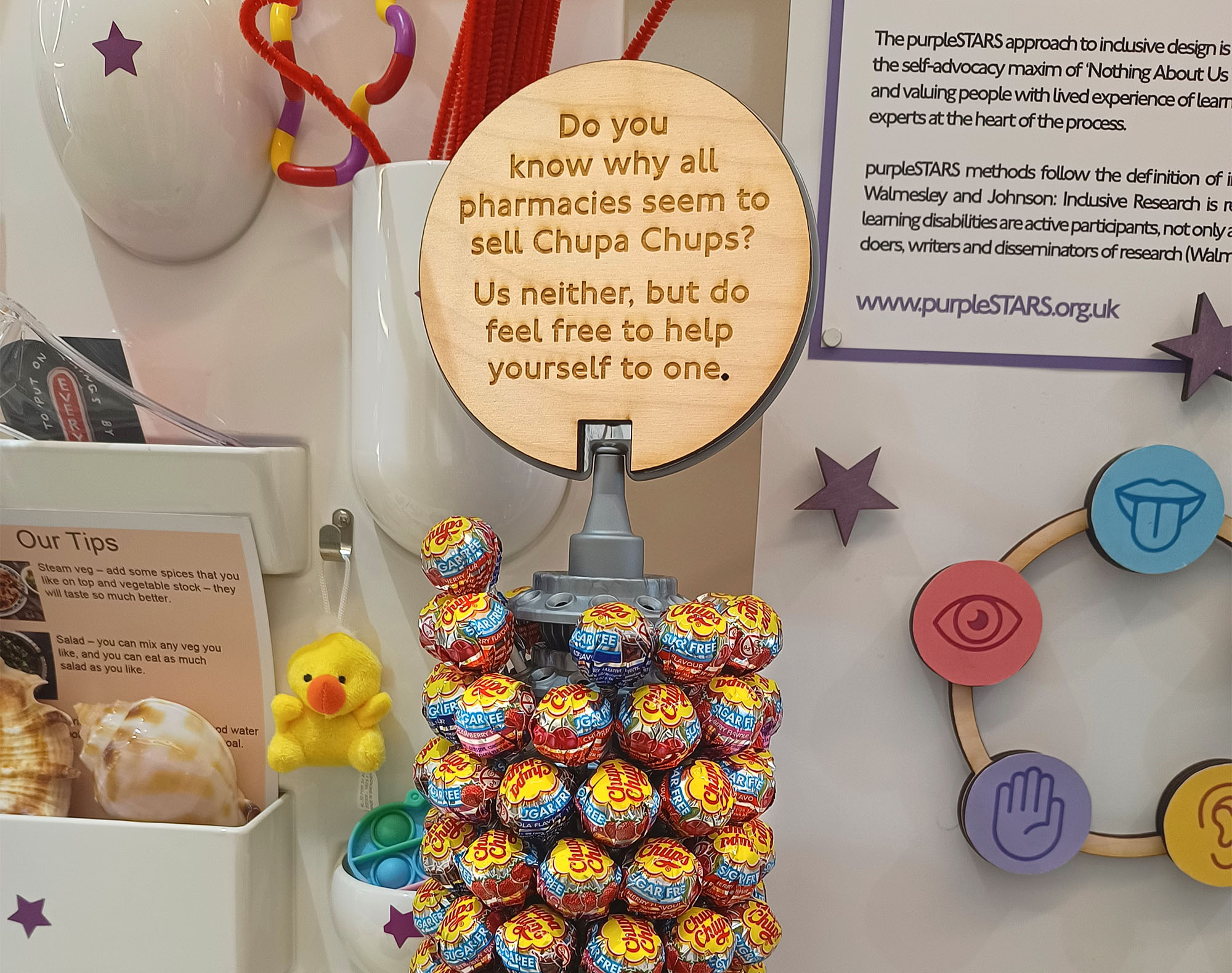

Doll notes that pharmacy teams also “need to consider the sensory experience within the pharmacy”. This includes limiting clutter on the counter, determining appropriate lighting for people with visual impairments and “managing noise levels”.

“In addition to improving physical and sensory accessibility, pharmacies can better support people with learning disabilities and ethnic minorities by focusing on communication. Staff should use clear patient communication styles and give people time to express their concerns and understand their medicines,” she says.

Corrinne Burns

“Providing materials in easy-to-understand formats, multiple languages and culturally sensitive content is essential to meet the diverse needs of these communities.”

Eleanor Brough, an architect commenting in a personal capacity, who led a session at the ‘Architecture of Pharmacies: Counter Culture’ exhibition at the Bromley by Bow Centre in east London (see Box) on 3 June 2024, says further changes to wider healthcare services may also need to be reflected in a community pharmacy space of the future.

The growth in social prescribing “might prompt links between pharmacies and broader health and wellbeing initiatives on offer in other places and services, [such as] leisure centres, parks, community centres, schools, with the potential for community pharmacies to be combined with other health and wellbeing businesses and community services on a single site”.

Dhital says the Architecture of Pharmacies study is the beginning of this kind of creative interdisciplinary research for pharmacy, using architecture and co-designed ideas to better support patients and help pharmacists and their teams to consider architectural thinking as part of healthcare expertise.

“Unfortunately, pharmacy spaces have not been explored in meaningful ways, especially with approaches involving diverse communities,” she says.

“We don’t fully understand what could make pharmacy spaces comfortable and engaging. During this research, we’re realising that to build on this knowledge we need to work collaboratively and in equitable ways with our communities, especially those with rich understanding of their neighbourhoods and with lived experience,” Dhital adds.

“If research is to inform pharmacy practice and policy in effective ways, it needs to engage with participatory and interdisciplinary thinking. Then there could be a real potential to make community pharmacies an even more significant hub of the community.”

Box: Unveiling hidden healing spaces

The first stage of the Architecture of Pharmacies project involved Dhital and her team carrying out a systematic review of 80 articles reporting on 80 studies, published between 1994 and 2020, relating to patients, staff, pharmacy spaces and health outcomes. The study concluded that “to optimise the delivery and experience of pharmacy health services, these spaces should be made more engaging”, adding that future applied research “could focus on optimising inclusive pharmacy design features”.

During the course of their research, the UCL team observed how little discourse there is around staff and patients’ experience of community pharmacy spaces.

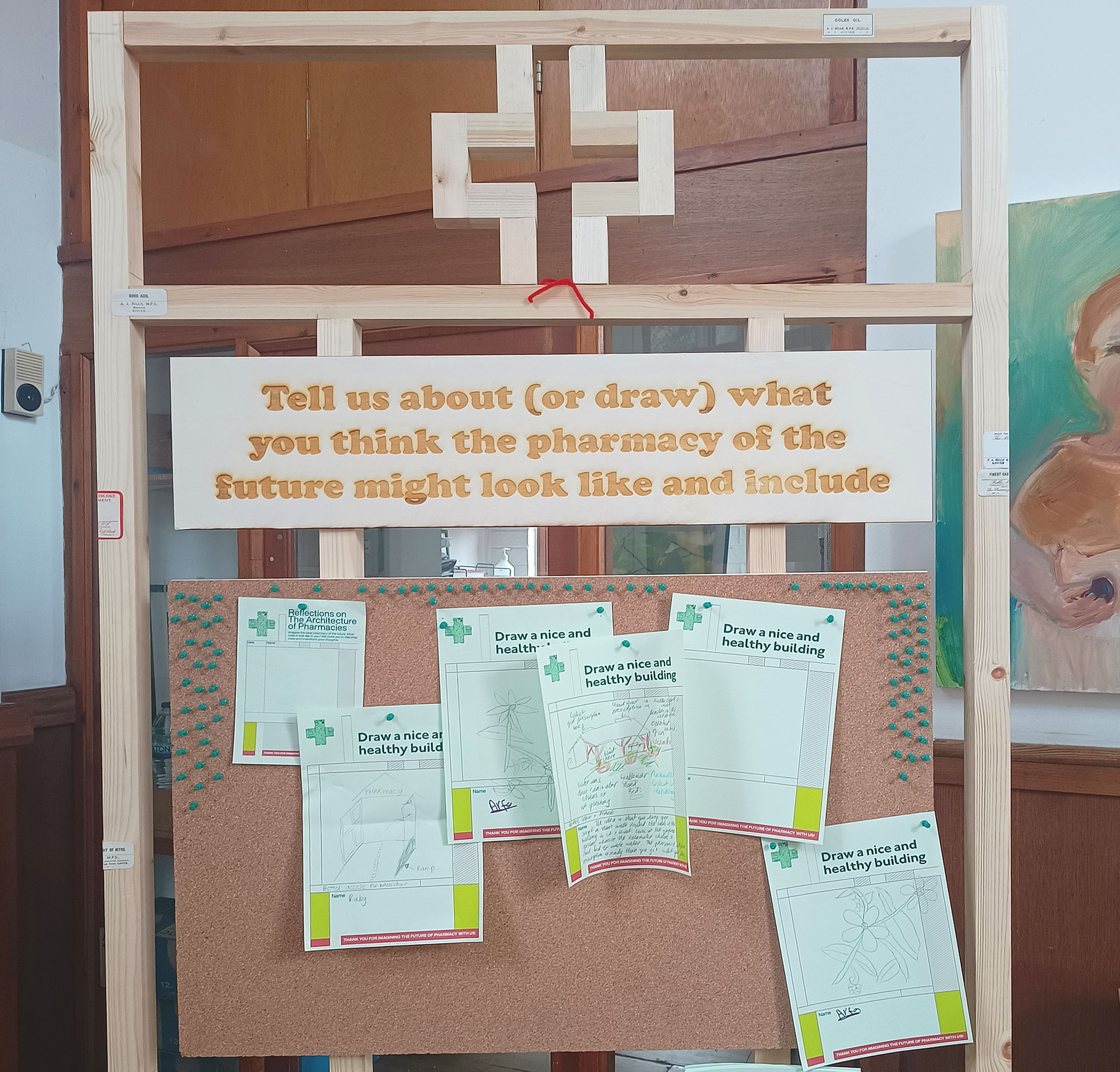

Dhital says that she noticed a “hesitancy and sometimes reluctance to express ideas” when discussing pharmacy design. “We therefore felt it was important to create an environment which enabled expression of such ideas and stimulated creative thinking about pharmacy spaces,” she says.

As a result, following a series of pharmacy workshops, and input from a variety of academic and lived experience experts, the team held the ‘Architecture of Pharmacies: Counter Culture’ exhibition at the Bromley by Bow Centre in east London, which ran from 29 May to 7 June 2024, with the aim of prompting discussions around how pharmacy spaces can be optimised to be more inclusive, promote health, and support pharmacy teams to achieve best practice.

For more information on the exhibition and the ‘Architecture of Pharmacies’ project, visit: www.architectureofpharmacies.com