roger askew / Alamy Stock Photo

Sodium valproate is a broad-spectrum anticonvulsant drug that has been on the UK market since 1973[1]. In the UK, it is licensed for the treatment of epilepsy and bipolar disorder and can also be considered in patients with episodic or chronic migraine[2].

Commonly used brands in the UK include Dyzantil (Aspire Pharma), Epilim (Sanofi), Episenta (Desitin Pharma) and Epival (Gerot Lannach UK).

The drug’s product information has included a warning about the possible risk of birth defects in the unborn children of women taking valproate since the 1970s, but as the risks have become better understood, regulators have issued stronger warnings and established stricter safeguards.

In this article, we will look at what has been put in place to protect against harm from sodium valproate in the UK and ask whether it is enough to prevent harm.

What are the risks associated with sodium valproate?

Since 1972, when sodium valproate was first licensed in the UK to treat epilepsy, evidence has emerged that it can cause physical and neurodevelopmental effects in children if taken by mothers during pregnancy.

Children exposed in utero to valproate are at a high risk of serious developmental disorder (up to 40% of cases) and/or congenital malformations (around 10% of cases)[3].

Data also show that children exposed to valproate in utero are around three times more likely to develop autistic spectrum disorder and five times more likely to have childhood autism, compared to the general population[3].

What measures have been put in place to reduce the risks of valproate?

In January 2015, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) issued a drug safety update highlighting the risks associated with sodium valproate[3]. At the time, the MHRA said that if the drug was the only treatment option, women of childbearing age should be given effective contraception. This usually means long-acting reversible contraception, such as a copper intrauterine device.

The following year, the MHRA produced a toolkit to support discussions between prescribers and female patients about the risks associated with taking valproate[4]. This included a patient guide to be issued to all women or girls of childbearing potential, and a patient card to be issued by pharmacists whenever valproate was dispensed to this group of patients.

However, since then, there have been even stricter measures put in place. In April 2018, the MHRA followed suit by also announcing that valproate must no longer be prescribed to women or girls of childbearing potential unless they are on a pregnancy prevention programme (PPP).

According to the MHRA, the PPP is applicable to “all premenopausal female patients unless the prescriber considers that there are compelling reasons to indicate that there is no risk of pregnancy”[5].

Those on a PPP are given materials needed to understand the risks posed by valproate, prescribed “highly effective” contraception — preferably a user-independent form such as an intrauterine device or implant — and undertake an annual review with their specialist[6].

The new regulatory guidance also included reducing pack sizes and adding warning labels. Further to this, it recommended that pharmacists should dispense valproate in whole packs whenever possible to ensure that patients are more likely to see the warnings on the information leaflet, which may not be included with partial packs of medicine.

“Every year, every woman on valproate needs to sign an annual risk acknowledgement form together with their healthcare professional, as her circumstances regarding the risk of pregnancy may change,” explains Alison Cave, chief safety officer at the MHRA.

Also in April 2018, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence amended its valproate guidelines to reflect the new regulatory position.

Have these measures worked?

Yes, but progress has been slow.

According to a Clinical Practice Research Datalink study, both new and repeat prescribing of valproate in girls and women of childbearing age declined between January 2010 and December 2019 across the UK[7].

However, about 3.3 per 10,000 pregnancies in the UK were exposed to valproate in 2017 — the equivalent to around 250 live births[8].

Furthermore, in 2020, a survey of 2,000 women with epilepsy — carried out by the charities Epilepsy Action, Epilepsy Society and Young Epilepsy — indicated that 18% of women taking valproate were unaware of the risks that the medicine could pose in pregnancy[9].

The results also revealed that nearly a third of women taking valproate (28%) had not been informed of the risks of the medicine in pregnancy, and 68% had not received any materials from the MHRA toolkit[9].

In the same year, Baroness Julia Cumberlege led the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Review, which found that women were still becoming pregnant while taking valproate, without any knowledge of the risks[10]. It estimated that hundreds of babies were being born each year after being exposed to valproate in utero, despite the teratogenic risk being well recognised[10].

The review led to calls for a register of all women taking antiepileptic drugs who become pregnant, which would include mandatory data reporting on the women and their children over their lifetimes. It also said that all women currently taking sodium valproate should be contacted for a medication review[10].

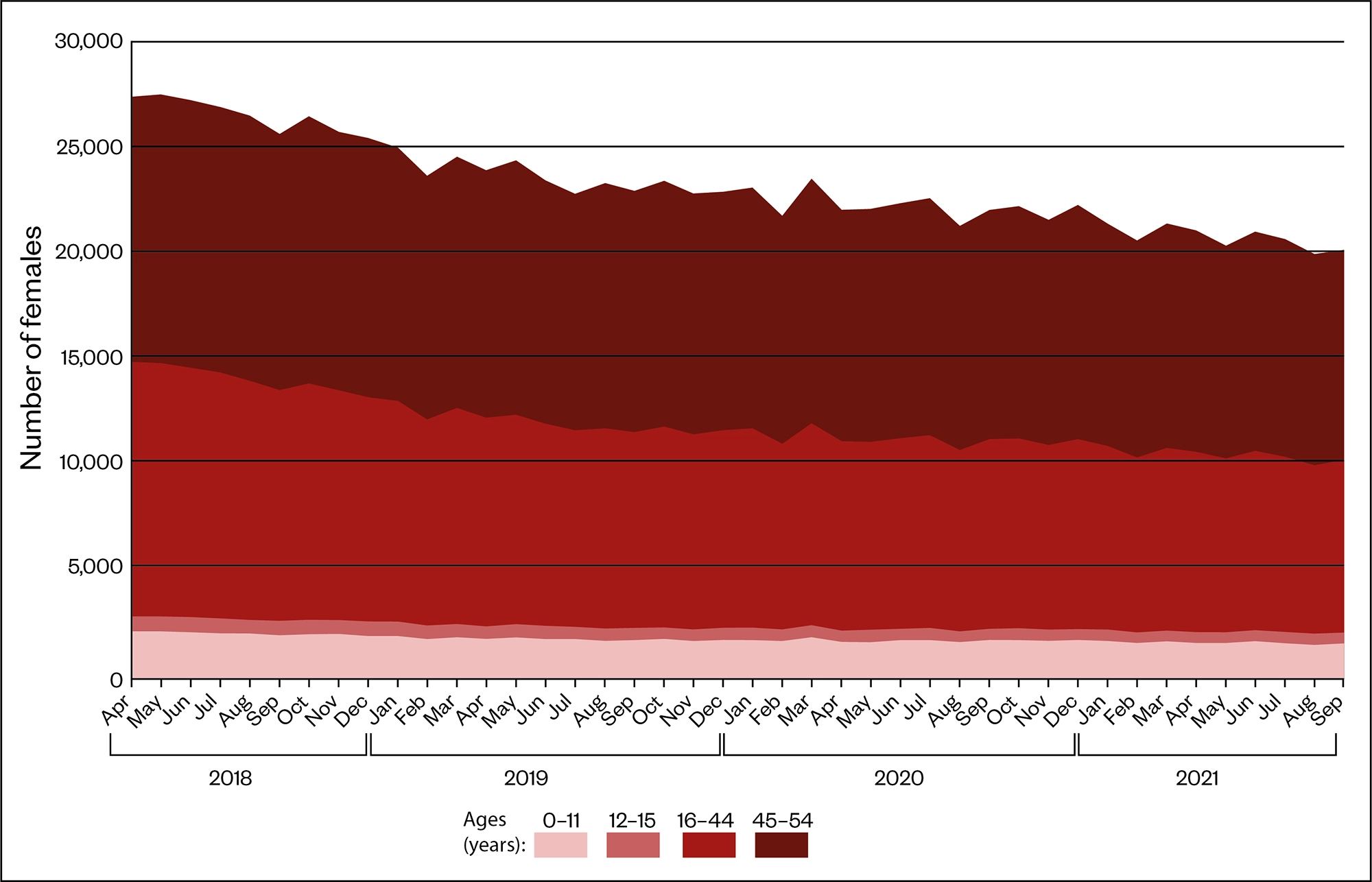

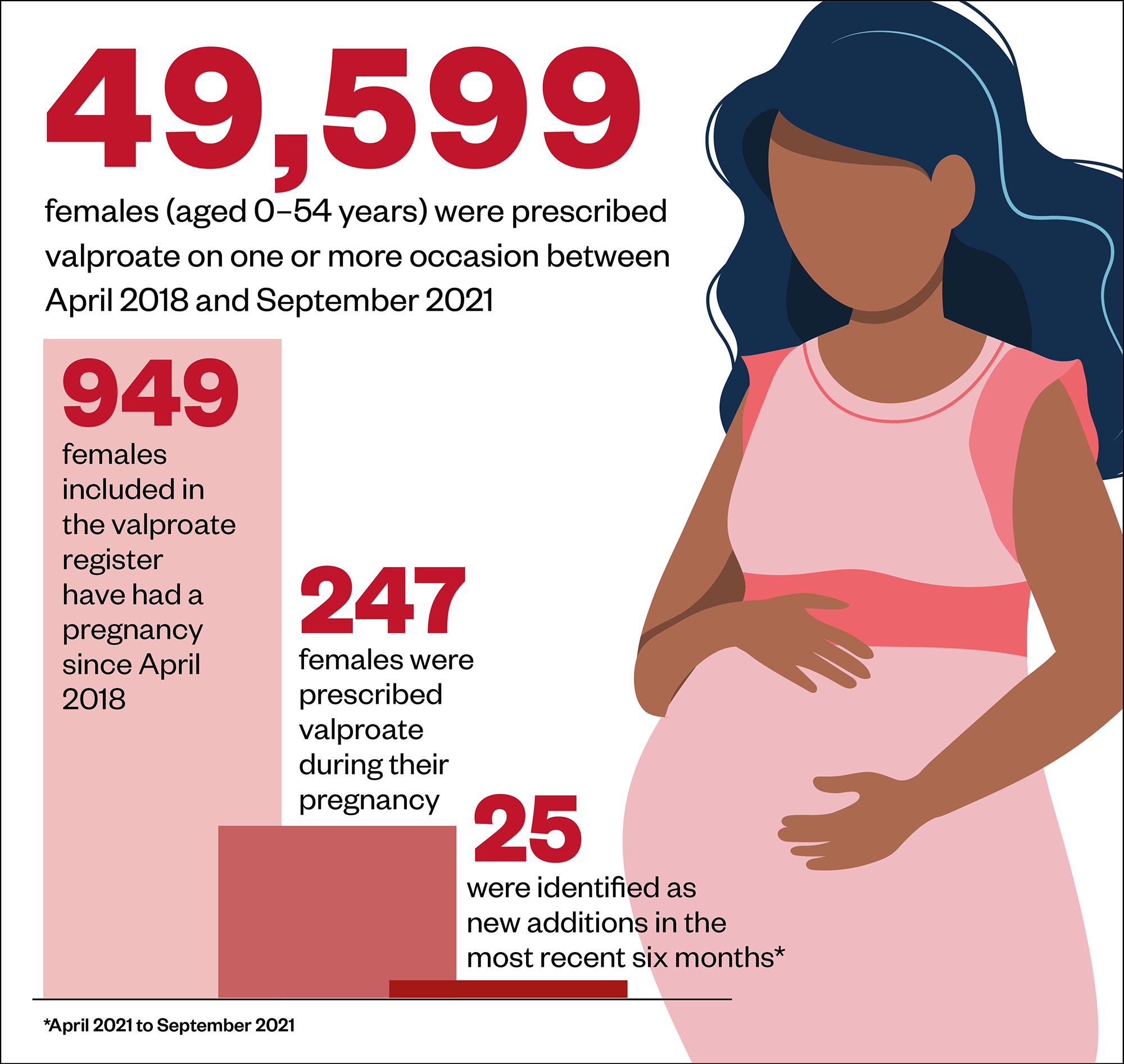

Since then, the MHRA launched a valproate registry in partnership with NHS Digital, using existing administrative data from England available from April 2018[11]. The registry included the number of females prescribed valproate, the number of pregnancies and if valproate continued to be prescribed during pregnancy or was stopped before. The aim was to track the implementation of the PPP and allow the MHRA to identify and investigate any exposures to sodium valproate during pregnancy and incidences where the PPP has not been followed.

Source: Medicines and Pregnancy Registry (March 2022)

How many women are still being prescribed valproate when pregnant?

According to figures published by NHS Digital in March 2022, 949 women in England on the valproate register have had a pregnancy since April 2018, 247 (26%) of whom were prescribed sodium valproate during their pregnancy[11].

Of these, 46 women were prescribed sodium valproate during their pregnancy in the most recent recording period, from October 2020 to September 2021, although this was a reduction from 65 women recorded in the same period the previous year.

Most recently, in April 2022, a major investigation carried out by The Sunday Times found that the drug was being dispensed by pharmacies in plain packets with the information leaflets missing or with stickers over the warnings[12].

Source: Medicines and Pregnancy Registry (March 2022)

What is the government doing about this?

In 2021, NHS England set a target of reducing the use of valproate in people who can get pregnant by 50% by 2023, although it is not clear what the baseline figure is.

Proposals set out in a consultation document published by the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) on 1 November 2021 called for sodium valproate to always be supplied in original packaging, regardless of any conditions set around original pack dispensing[13].

The DHSC is still analysing feedback from the consultation. On 25 April 2022, a spokesperson told The Pharmaceutical Journal that it did not have an update regarding implementation of these proposals.

“We have … worked with the DHSC to seek views from the UK public on requirements to ensure medicines that contain sodium valproate are always dispensed in the original manufacturer’s packaging so that the important safety information on risks in pregnancy is provided with every dispensed prescription,” says Cave.

“If there are examples where this information has not been provided we would investigate this.”

However, Jeremy Hunt, former health secretary and chair of the House of Commons Health and Social Care Committee, went even further and called for a ban on prescribing sodium valproate to pregnant women with epilepsy.

Speaking in the House of Commons on 19 April 2022, Hunt said: “Last year, the government consulted on putting warning labels on valproate. Is it not time to go much further and ban the prescription of sodium valproate to epileptic pregnant mothers?”

In response, health secretary Sajid Javid said: “It is right that we reconsider this and make sure that sodium valproate, and any other medicine, is given only in the clinically appropriate setting.”

However, for many women with epilepsy, valproate is the only medicine that controls their seizures and, until effective alternatives are available, these women will continue to rely on valproate, despite the risks.

On 29 April 2022, Alison Cave, chief safety officer at the MHRA told The Pharmaceutical Journal that its safety work on sodium valproate was “ongoing” and that it would continue to “review, adapt and implement regulatory measures” where appropriate to enable the continued safe use of valproate in individuals who can get pregnant where there are no other viable options available.

“In addition, we have worked extensively with patients, the public and healthcare professionals to minimise prescribing of valproate in women who may become pregnant and we continue to do so through the Valproate Stakeholder’s Network, which is helping inform us of the effectiveness of our measures.”

Are there any other antiepileptic medicines that could also increase the risk of congenital malformations?

Unfortunately, yes. In January 2021, the MHRA released the results of a safety review, which highlighted that carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin and topiramate were all associated with an increased risk of having a baby born with a physical birth abnormality[14].

In the review, lamotrigine and levetiracetam were said to be safer than other antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy because they were not linked with an increased risk of birth abnormalities compared with the general population.

A patient safety leaflet, developed as a result of this review, gives women access to authoritative and up-to-date information on risks in pregnancy of epilepsy medicines, so that together with their healthcare professional, they can make informed decisions about which epilepsy medicine is right, given their individual circumstances.

In a parliamentary written answer on 4 March 2021, health minister Nadine Dorries said that extending the valproate registry to include all women prescribed an antiepileptic medicine had been “prioritised within the next phase of development”.

She also said that work was “ongoing” to extend the registry to include women in the devolved administrations; Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The valproate registry has since been extended and reports published on 30 September 2021 and 31 March 2022 included all antiepileptic drugs.

According the MHRA, the registry will continue to be developed so that more systematic data on non-adherence to all regulatory requirements can be obtained. It added that although the registry data does not yet give detailed information about the indication or dose of medication, an increase in usage of some of the antiepileptics may represent diversion or switching away from more harmful alternatives.

READ MORE: Valproate use in women: minimising the risks

- 1Mahase E. Sodium valproate continues to be prescribed in hundreds of pregnancies, data show. The BMJ. 2022.https://www.bmj.com/content/377/bmj.o1013 (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 2SODIUM VALPROATE. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/sodium-valproate.html (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 3Medicines related to valproate: risk of abnormal pregnancy outcomes. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2015.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/medicines-related-to-valproate-risk-of-abnormal-pregnancy-outcomes (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 4New toolkit supports better understanding of the risks of valproate and pregnancy. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2016.https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-toolkit-supports-better-understanding-of-the-risks-of-valproate-and-pregnancy (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 5Valproate Pregnancy Prevention Programme: actions required now from GPs, specialists, and dispensers. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2018.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/valproate-pregnancy-prevention-programme-actions-required-now-from-gps-specialists-and-dispensers (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 6Information on the risks of Valproate use in girls (of any age) and women of childbearing potential (Epilim, Depakote, Convulex, Episenta, Epival, Kentlim, Orlept, Sodium Valproate, Syonell, Valpal, Belvo & Dyzantil). Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/950802/107995_Valproate_HCP_Booklet_DR15_v07_DS_07-01-2021.pdf (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 7CPRD STUDY MONITORING THE USE OF VALPROATE IN GIRLS AND WOMEN IN THE UK: January 2010 to December 2019. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency . 2020.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/880614/CPRD_valproate_usage_report_DSU_Feb_2020_final.pdf (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 8Valproate medicines: are you acting in compliance with the pregnancy prevention measures? Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2018.https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/valproate-medicines-are-you-in-acting-in-compliance-with-the-pregnancy-prevention-measures (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 9Almost one-fifth of women taking sodium valproate for epilepsy still not aware of risks in pregnancy, survey shows. Epilepsy Today. 2017.https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/news/news/almost-one-fifth-women-taking-sodium-valproate-epilepsy-still-not-aware-risks-pregnancy (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 10Julia C. First Do No Harm The report of the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review. APS Group 2020. https://www.webarchive.org.uk/wayback/archive/20200721101148mp_/https://www.immdsreview.org.uk/downloads/IMMDSReview_Web.pdf (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 11Medicines and Pregnancy Registry. NHS Digital. 2022.https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mi-medicines-and-pregnancy-registry (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 12Lintern S. A scandal worse than thalidomide. The Sunday Times. 2022.https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/the-new-thalidomide-d5lmlwvdc (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 13Original pack dispensing and supply of medicines containing sodium valproate. Department of Health and Social Care. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/original-pack-dispensing-and-supply-of-medicines-containing-sodium-valproate/original-pack-dispensing-and-supply-of-medicines-containing-sodium-valproate (accessed 4 May 2022).

- 14Antiepileptic drugs: review of safety of use during pregnancy. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. 2021.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/public-assesment-report-of-antiepileptic-drugs-review-of-safety-of-use-during-pregnancy/antiepileptic-drugs-review-of-safety-of-use-during-pregnancy (accessed 4 May 2022).

1 comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I was aware of the risks but needed to update my knowledge