In 2023, US officials raised serious concerns about an increase in the presence of xylazine in illegal fentanyl supplies, with the White House calling it an “emerging threat”. Known as “tranq”, or “tranq dope” when cut with fentanyl or heroin, it has dangerous sedative effects and is being implicated in a growing number of drug-related deaths.

While not yet anywhere near the scale seen in the United States, xylazine has made it to the UK, with the first death reported in the West Midlands in May 2022. In April 2024, researchers from King’s College London (KCL) found xylazine present not only in heroin supplies, but also in counterfeit medicines, including benzodiazepines, codeine and tramadol[1].

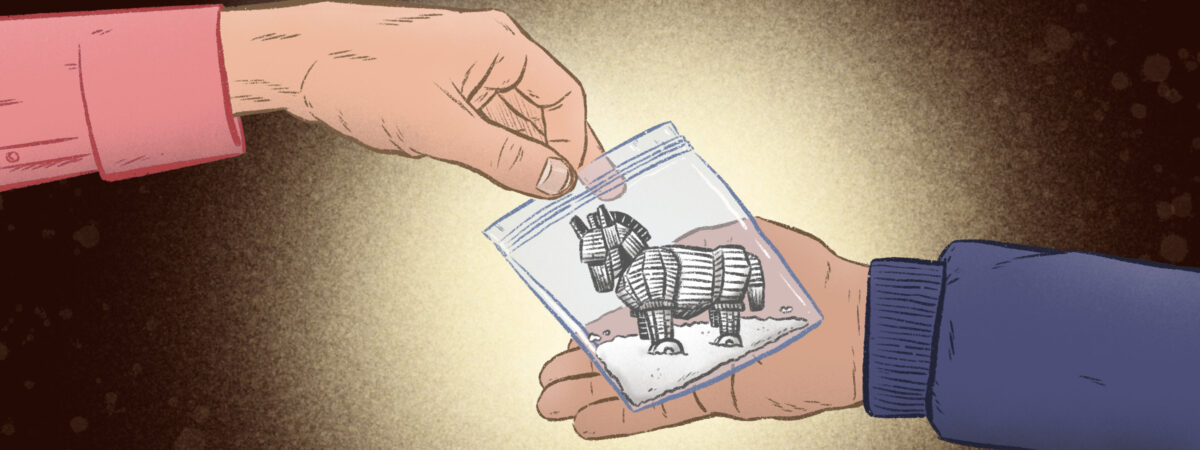

What is xylazine?

A powerful animal tranquiliser, xylazine is a non-opioid sedative painkiller and muscle relaxant, first developed in the 1960s[2]. Licensed for use in veterinary medicine, it was never approved for use in humans because of the risk of severe central nervous system depression. The analgesic, hypnotic and anaesthetic effects it produces relate to its affinity for the alpha-2 adrenergic receptor and, pharmacologically, it has similarities to drugs such as clonidine, which is licensed for hypertension, migraines and menopausal symptoms, including hot flushes.

Xylazine overdose can be fatal in itself, but the vast majority of overdoses that have been reported in the past few years have been alongside other drugs, particularly fentanyl. The sedative effects of xylazine, which slow down breathing and heart rate, and lower blood pressure, are more dangerous when combined with opioids, which have similar effects. It is also a potent vasoconstrictor and chronic use of the drug can lead to the development of skin ulcers because of limited blood flow to the skin.

Xylazine comes as a liquid solution for injection but can be dried into a white or brown powder. Routes of administration include intravenous, intramuscular, intranasal, oral and via vaping. It has a rapid onset of action within minutes and its effects can last eight hours or longer depending on the dose, route of administration and whether it was mixed with other drugs[3].

How many deaths have been associated with xylazine in the UK?

After tracking coroner’s reports, toxicology information and drug testing, researchers at KCL found that, by the end of August 2023, xylazine had been identified in 16 biological samples from overdose cases, 11 of which were fatal, 2 non-fatal and 3 that could not be reported on while the coroner’s inquiry was ongoing[1]. At the time of the KCL research, coroners had concluded inquiries for three of the fatal cases and had directly implicated xylazine in all of these deaths. The deaths were spread across England, with two deaths in Scotland (see Figure). In the nine fatal cases where full toxicology was available, individuals also had other drugs in their system, mostly heroin, another strong opioid, or both.

The people who are using xylazine are thinking that they’re using other drugs

Caroline Copeland, senior lecturer in pharmacology and toxicology, King’s College London

Study lead Caroline Copeland, senior lecturer in pharmacology and toxicology at KCL, says the data show that the first death reported in the West Midlands in May 2022 was not a “one off”. Since the research paper was published, that number has grown to at least 18 deaths, she says. “As far as we can see, there is no active market for xylazine and the people who are using it are thinking that they’re using other drugs. I don’t honestly know if the dealers know that’s what they’re selling; I think it goes further back in the chain.”

When looked at in the context of all UK drug deaths, the 11 fatalities account for around 0.002% of these, but that is probably a “gross underestimate” of the true number, says Copeland. Extrapolating from the US experience, where there has been a 20-fold increase in deaths linked to xylazine since 2015, the UK could anticipate more than 220 deaths by 2028, the team concluded. That would be more than those caused by tramadol, fentanyl, oxycodone, codeine or dihydrocodeine.

Where has xylazine been found?

The KCL researchers found xylazine in 14 drug samples from across Wales, England and Scotland where individuals had purchased counterfeit medicines and sent them to the Welsh Emerging Drug and Identification of Novel Substances (WEDINOS) service in Wales for anonymous testing. Two samples were in THC vapes and the others had been sold as benzodiazepines, codeine and tramadol. Evidence from five drug seizures in England also supports the premise that xylazine is being used as an adulterant in the UK, according to the researchers.

While it is most likely that xylazine had been used as an adulterant in heroin or other strong opioid supplies in the fatal overdoses, the WEDINOS evidence suggests it could also have come from counterfeit tablets.

In one of the drug seizures in London, drug testing showed a specific mix: xylazine; heroin; the benzodiazepine bromazolam; the nitazenes metonitazene and protonitazene; caffeine; and paracetamol. This exact mixture was found subsequently in deaths in Scotland and England, explains Copeland. “They could have just happened to take that mix as well, but it suggests to me that it’s been pre-mixed like that and then distributed.”

What are the signs of xylazine overdose and how is it treated?

An overdose with heroin that has been cut with xylazine would present in a similar way to a straightforward opioid overdose. Advice for clinicians from the New York State Department of Health states that while opioids cause severe respiratory depression, with xylazine in the mix, severe impacts on the central nervous system can lead to airway compromise[3].

Naloxone will still work against any co-administered opioid . . . but when you do that in a mixed opioid xylazine overdose, you would . . . need potentially more respiratory support

Caroline Copeland, senior lecturer in pharmacology and toxicology, King’s College London

“It’s a sedative like the opioids but it works in a different way, so naloxone, which is used for opioid overdose, won’t work,” explains Copeland. “It will still work against any co-administered opioid and, in fact, naloxone is very safe, but when you do that in a mixed opioid xylazine overdose, you would need to be more vigilant and would need potentially more respiratory support.”

A further complicating factor is that some xylazine overdoses involve nitazenes, which themselves are potent opioids that need more doses of naloxone, she explains, adding that xylazine would not necessarily be picked up on clinical toxicology screens done in hospital. “The majority of NHS labs won’t be capturing them.”

When it comes to treatment for the ulcers seen with chronic xylazine use, careful wound care is essential, including cleaning with soap, water or saline (not alcohol or hydrogen peroxide) and keeping it moist and covered.

What is the UK government doing to curb xylazine-related harm?

The government announced in March 2024 that it would be making xylazine a Class C drug and would be providing information to harm reduction services about its potential use as an adulterant in other illegal drugs[4]. It added that the Department of Health and Social Care, Home Office and law enforcement would “continue to monitor the prevalence and harms of xylazine and synthetic opioids, including through analysis of seized or submitted drug samples and patient and post-mortem toxicology”.

But the lack of drug testing in the UK is hindering the ability to get a sense of the true prevalence of xylazine use in the community. At the moment, the only in-person drug-checking service is open once a month in Bristol; however, Aberdeen and Dundee have recently applied for Home Office licenses to open similar services. Other countries have effective drug-checking facilities in place — notably the Netherlands, where public-funded services have operated nationally since 1992.

Point-of-use test strips for xylazine could be an important harm reduction tool

Adam Holland, drug-related harm researcher, University of Bristol

There are point-of-use test strips for xylazine on the market. Adam Holland, a drug-related harm researcher at the University of Bristol who co-authored the KCL research, notes these tests have some limitations in terms of the potential to give false reassurance, “but if people are taught to understand these limitations, they could be an important harm reduction tool”.

Amira Guirguis, MPharm programme director at Swansea University and an expert in novel psychoactive substances, agrees that drug checking, if done properly, would be “an incredible way to reduce harm and deaths”. But adds that “you don’t really look for what you’re not expecting, and that’s the challenge of having a new drug emerging on the market”.

“We need to understand the patterns of use, the behaviours, why people are doing it, so we can actually prepare for that,” she says.

Copeland adds: “It’s here and it’s going to continue to be here. It’s a good thing that the government is planning to control xylazine as a Class C, but how much will that change behaviours when a lot of people don’t even know they’re possessing it? What we need to do is stem the demand for the drugs and that is by getting people the help that they need.”

What can pharmacy staff do to support people who misuse drugs to minimise risks of xylazine?

Pharmacists potentially have a role here; first, for those working in intensive care to recognise xylazine toxicity, as well as those in the community, where raising awareness will be essential, says Guirguis. She points to advice issued by US officials on being aware of the symptoms and providing naloxone for overdose[5]. The advice also recommends the recovery position and rescue breaths in patients who have overdosed because of the effect of xylazine in causing breathing to slow.

Education is really needed, along with drug checking and referring people to treatments

Amira Guirguis, MPharm programme director, Swansea University

Work is beginning in the UK to make sure that people who use illegal drugs are aware of the potential risks of xylazine as an adulterant with heroin and other drugs, as well as the importance of seeking skin care for any wounds because these can quickly become infected and lead to amputation. Information is being shared with patients through harm reduction services, such as drug treatment and rehabilitation services, as well as via the national anti-drug advisory service FRANK.

“Education is really needed, along with drug checking and referring people to treatments, because the withdrawal symptoms are severe and people might need to be detoxed and/or detoxified,” says Guirguis.

- 1Copeland CS, Rice K, Rock KL, et al. Broad evidence of xylazine in the UK illicit drug market beyond heroin supplies: Triangulating from toxicology, drug‐testing and law enforcement. Addiction. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16466

- 2Sue KL, Hawk K. Clinical considerations for the management of xylazine overdoses and xylazine‐related wounds. Addiction. 2023;119:606–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.16388

- 3Xylazine: What Clinicians Need to Know. New York State Department of Health. 2023. https://www.health.ny.gov/publications/12044.pdf (accessed 8 May 2024)

- 4Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs. Government response to the ACMD’s advice on xylazine and related compounds. Gov.uk. 2024. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/response-to-the-acmds-report-on-xylazine-and-related-compounds/government-response-to-the-acmds-advice-on-xylazine-and-related-compounds (accessed 8 May 2024)

- 5What You Should Know About Xylazine. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/deaths/other-drugs/xylazine/faq.html#illegal (accessed 8 May 2024)