Shutterstock.com

Open access article

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has made this feature article free to access in order to help healthcare professionals stay informed about an issue of national importance.

To learn more about coronavirus, please visit: https://www.rpharms.com/resources/pharmacy-guides/wuhan-novel-coronavirus.

A novel strain of coronavirus — SARS-CoV-2 — was first detected in December 2019 in Wuhan, a city in China’s Hubei province with a population of 11 million, after an outbreak of pneumonia without an obvious cause. The virus has now spread to over 200 countries and territories across the globe, and was characterised as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020[1],[2].

As of 3 May 2021, there were 152,534,452 laboratory-confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection globally, with 3,198,528 reported deaths. The number of cases and deaths outside of China overtook those within the country on 16 March 2020[3].

As of 3 May 2021, there have been 4,421,850 confirmed cases of the virus in the UK and 127,539 of these have died (in all settings, within 28 days of the test).

This article gives a brief overview of the new virus and what to look out for, and will be updated weekly. It provides answers to the following questions:

Where has the new coronavirus come from?

What social distancing measures are being taken in the UK?

What is happening with testing for COVID-19?

What should I do if a patient thinks they have COVID-19?

What can I do to protect myself and my staff?

What about ‘business as usual’ during the pandemic?

Will the government provide financial help during the pandemic?

How can cross-infection be prevented?

Where can I find information on managing COVID-19 patients?

Is the coronavirus pandemic likely to precipitate medicines shortages?

Are there national clinical trials of potential drugs to treat COVID-19?

Is there a vaccine for COVID-19 and, if so, will pharmacy staff be involved in its roll out?

What are coronaviruses?

SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a family of single-stranded RNA viruses known as coronaviridae, a common type of virus which affects mammals, birds and reptiles.

In humans, it commonly causes mild infections, similar to the common cold, and accounts for 10–30% of upper respiratory tract infections in adults[4]. More serious infections are rare, although coronaviruses can cause enteric and neurological disease[5]. The incubation period of a coronavirus varies but is generally up to two weeks[6].

Previous coronavirus outbreaks include Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), first reported in Saudi Arabia in September 2012, and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), identified in southern China in 2003[7],[8]. MERS infected around 2,500 people and led to more than 850 deaths while SARS infected more than 8,000 people and resulted in nearly 800 deaths[9],[10]. The case fatality rates for these conditions were 35% and 10%, respectively.

SARS-CoV-2 is a new strain of coronavirus that has not been previously identified in humans. Although the incubation period of this strain is currently unknown, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that symptoms may appear in as few as 2 days or as long as 14 days after exposure[6]. Chinese researchers have indicated that SARS-CoV-2 may be infectious during its incubation period[11].

The number of cases and deaths outside of China overtook those within it on 16 March 2020

Where has the new coronavirus come from?

It is currently unclear where the virus has come from. Originally, the virus was understood to have originated in a food market in Wuhan and subsequently spread from animal to human. Some research has claimed that the cross-species transmission may be between snake and human; however, this claim has been contested[12],[13].

Mammals such as camels and bats have been implicated in previous coronavirus outbreaks, but it is not yet clear the exact animal origin, if any, of SARS-CoV-2[14].

How contagious is COVID-19?

Increasing numbers of confirmed diagnoses, including in healthcare professionals, has indicated that person-to-person spread of SARS-CoV-2 is occurring[15]. The preliminary reproduction number (i.e. the average number of cases a single case generates over the course of its infectious period) is currently estimated to be between 1.4 to 2.5, meaning that each infected individual could infect between 1.4 and 2.5 people[16].

Similarly to other common respiratory tract infections, MERS and SARS are spread by respiratory droplets produced by an infected person when they sneeze or cough[17]. There is also some evidence that SARS-CoV-2 can spread by airborne transmission. Measures to guard against the infection work under the current assumption that SARS-CoV-2 is spread in the same manner.

How is COVID-19 diagnosed?

As this coronavirus affects the respiratory tract, common presenting symptoms include fever and dry cough, with some patients presenting with respiratory symptoms (e.g. sore throat, nasal congestion, malaise, headache and myalgia) or even struggling for breath.

In severe cases, the coronavirus can cause pneumonia, severe acute respiratory syndrome, kidney failure and death[18].

The case definition for COVID-19 is based on symptoms regardless of travel history or contact with confirmed cases. Diagnosis is suspected in patients with a new, continuous cough, fever or a loss or changed sense of normal smell or taste (anosmia). A diagnostic test has been developed, and countries are quarantining suspected cases[19].

Box 1: Who qualifies as a suspected COVID-19 case?

Individuals with:

- New continuous cough AND/OR

- Temperature ≥37.8°C AND/OR

- Anosmia (a loss or changed sense of normal smell or taste)

Individuals with any of the above symptoms but who are well enough to remain in the community should stay at home for 10 days from the onset of symptoms and get tested. Households should all self-isolate for 10 days if one member shows symptoms.

What social distancing measures are being taken in the UK?

The government launched its coronavirus action plan on 3 March 2020, which details four stages: contain, delay, mitigate, research[20]. On 12 March 2020, the UK moved to the delay phase of the plan and raised the risk level to ‘high’.

On 16 March 2020, Johnson announced social distancing measures, such as working from home and avoiding social gatherings, as well as household isolation for those with symptoms[21],[22].

Further social distancing measures were announced on 18 March 2020, including closing all schools in the UK except for vulnerable children and those of key workers, such as pharmacists and other health and social care staff, teachers and delivery drivers. Restaurants, cafes, pubs, leisure centres, nightclubs, cinemas, theatres, museums and other businesses were also told to close.

On 22 March 2020, Johnson announced that the most clinically extremely vulnerable people, including those who have received organ transplants, are living with severe respiratory conditions or specific cancers, and some people taking immunosuppressants, should stay in their homes for at least the next 12 weeks (see Box 2).

Since this date, shielding in England, Scotland and Wales has been eased and brought back in several times in line with lockdown restrictions. And on 16 February 2021, a new risk assessment model was introduced in England to help clinicians identify adults with multiple risk factors that make them more vulnerable to COVID-19, resulting in an additional 1.7 million people being added to the shielding list. Shielding ended in England and Wales on 1 April 2021 and in Scotland on 26 April 2021.

Box 2: Shielding from COVID-19

Those classed as “clinically extremely vulnerable” may include the following (disease severity, history or treatment levels will also affect who is in this group):

- Solid organ transplant recipients

- People with cancer who are undergoing active chemotherapy

- People with lung cancer who are undergoing radical radiotherapy

- People with cancers of the blood or bone marrow such as leukaemia, lymphoma or myeloma who are at any stage of treatment

- People having immunotherapy or other continuing antibody treatments for cancer

- People having other targeted cancer treatments which can affect the immune system, such as protein kinase inhibitors or PARP inhibitors

- People who have had bone marrow or stem cell transplants in the last 6 months, or who are still taking immunosuppression drugs

- People with severe respiratory conditions including all cystic fibrosis, severe asthma and severe chronic obstructive pulmonary

- People with rare diseases that significantly increase the risk of infections (such as severe combined immunodeficiency, homozygous sickle cell)

- People on immunosuppression therapies sufficient to significantly increase risk of infection

- Adults with Down’s syndrome

- Adults on dialysis or with chronic kidney disease (stage 5)

- Women who are pregnant with significant heart disease, congenital or acquired

- Other people who have also been classed as clinically extremely vulnerable, based on clinical judgement and an assessment of their needs. GPs and hospital clinicians have been provided with guidance to support these decisions

A strict lockdown started in the UK on 23 March 2020, with people told to stay at home except to buy essential food and medicines, one form of exercise a day, any medical need, and travelling to and from essential work. Gatherings of more than two people in public was not allowed and all shops selling non-essential goods, libraries, playgrounds, outdoor gyms and places of worship closed. All social events, including weddings, baptisms and other ceremonies, but excluding funerals were cancelled.

A relaxation of the lockdown was announced by Johnson on 10 May 2020. The government published a 60-page ‘recovery strategy’ on 11 May 2020, which sets out the next phases of the UK’s response to the virus, including easing some social restrictions, getting people back to work and reopening schools.

Local lockdowns were introduced at the end of June 2020 to try to control the spread of coronavirus in particular regions in England but cases continue to rise and a second national lockdown was imposed from 5 November 2020 for four weeks. A three-tier system of restrictions will follow the national lockdown in England. In Scotland, a five-level alert system was introduced on 2 November, which will allow different restrictions to be imposed in local areas depending on the prevalence of the infection. A fire-break lockdown came into force in Wales from 23 October 2020, and ran until 9 November 2020.

On 19 December 2020, new tier-four restrictions were imposed in London, Kent and Essex and other parts of the South East of England, meaning that individuals in those areas had to stay at home and not meet up with other households. On 31 December 2020, further areas of England including the Midlands, North East, parts of the North West and parts of the South West were also escalated to tier four.

A new national lockdown was imposed in England and Scotland from 5 January 2021, and similar restrictions were introduced in Wales shortly after. The lockdowns began to lift in steps from the end of March 2021.

What is happening with testing for COVID-19?

Tests can now be accessed by anyone with symptoms via nhs.uk/coronavirus.

An NHS test and trace service was launched across England on 28 May 2020, with similar services starting in Scotland and Wales around the same time. Anyone who tests positive for the virus is contacted to share information about their recent interactions. People identified as being in close contact with someone who tests positive will have to self-isolate for 10 days, regardless of whether they have symptoms.

Testing is also now available to care home staff and residents in England, and NHS workers where there is a clinical need, whether or not they have symptoms.

Pharmacy staff in England and Scotland should book tests online via gov.uk and they will be conducted at drive-through testing sites across the country, as well as via home testing kits.

Pharmacy staff in Wales with symptoms of COVID-19 are able to access testing through their Local Health Board.

The government has also announced the start of a new national antibody testing programme, with plans to provide antibody tests to NHS and care staff in England from the end of May 2020. Clinicians will also be able to request the tests for patients in both hospital and social care settings if they think it is appropriate.

Regular testing of asymptomatic patient-facing staff delivering NHS services using lateral flow antigen tests was introduced in NHS trusts in November and expanded to primary care services in December 2020.

What should I do if a patient thinks they have COVID-19?

Patients have been advised not to go to their community pharmacy if they are concerned that they have COVID-19. Those with a new, continuous cough or a high temperature or anosmia (a loss or changed sense of normal smell or taste) who live alone should self-isolate for 10 days from the onset of symptoms. Households should all self-isolate for 10 days if one member shows symptoms[22]. There is no need for people with minor symptoms to telephone NHS 111.

However, given the outbreak has coincided with the cold and flu season, it is likely that patients may present in the pharmacy with queries about the virus, or with concerns about their cold or flu symptoms.

Community pharmacies were told by NHS England and NHS Improvement on 27 February 2020 that, in the unlikely event that a suspected case does present, they must prepare a “designated isolation space”[23].

If the pharmacy does not have a suitable room to isolate a suspected patient, an area that would keep a patient at least two metres away from staff and other patients in the pharmacy should be prepared so that it can be cordoned off.

Patients who present with a new, continuous cough or a high temperature or anosmia should be told to return home immediately and self-isolate. If, in the clinical judgement of the pharmacist, the person is too unwell to return home, they and any accompanying family should be invited into the designated isolation space where emergency services should be contacted.

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society is publishing ongoing guidance on contingency planning for COVID-19, which includes measures to protect the pharmacy team, such as limiting the number of people within the pharmacy at the same time, keeping at least two metres apart from staff and people coming into the pharmacy, and sectioning the pharmacy to encourage social distancing with floor markings (using tape) or barriers. The RPS has also produced a table to help pharmacists distinguish between COVID-19, a cold, the flu and hayfever.

Those with cold and flu symptoms that are not indicative of COVID-19 should be managed as usual, or using the pathway developed by The Pharmaceutical Journal.

The General Pharmaceutical Council said on 3 March 2020 that it recognises pharmacists may need to depart from established procedures in order to care for patients during the coronavirus outbreak and that regulatory standards are designed to be flexible and to provide a framework for decision-making in a wide range of situations.

In a joint statement with ten other health regulators, the GPhC said: “Where a concern is raised about a registered professional, it will always be considered on the specific facts of the case, taking into account the factors relevant to the environment in which the professional is working”.

What can I do to protect myself and my staff?

An updated standard operating procedure (SOP) for community pharmacies, published on 22 March 2020, sets out measures to protect pharmacy staff, including advising customers to keep a distance of at least two metres from other people, limiting entry and exit to the pharmacy and installing full screens to protect members of staff from airborne particles (see Learning article section ‘Enforcing social distancing’ for further details).

Following some confusion early on in the pandemic about whether community pharmacists should wear personal protective equipment (PPE), Public Health England updated its guidance on 23 July 2020 to say that pharmacy staff, both in clinical and non-clinical roles, should wear a type I, type II or type IIR facemask if the environment is not COVID-19 secure, using social distancing, optimal hand hygiene, frequent surface decontamination, ventilation and other measures where appropriate.

This brings the PHE guidance in line with that from the RPS, which says that pharmacy staff working in community pharmacies and general practice should wear fluid-resistant surgical masks if they are unable to maintain a social distance of 2 metres from patients and staff, and emphasises that it is still important to try to maintain social distance when wearing surgical masks wherever possible. The RPS also advises that gloves, apron and surgical masks should be worn by staff in direct contact with a patient, for example, when a person is too unwell to go home and is being cared for in the designated isolation space.

PPE can be ordered for free via the government’s PPE portal.

On 5 June 2020, the DHSC announced that all staff in hospitals in England will have to wear surgical masks from 15 June 2020, regardless of the clinical area in which they work.

Guidance has been issued by pharmacy organisations on how community pharmacies in England can accept patient returns of unwanted medicines while minimising risk to pharmacy teams. Since coronaviruses can survive on certain surfaces for up to five days, it recommends that all returns should be double bagged and placed directly in waste medicines bins. Controlled Drugs should be double bagged and placed in the CD cabinet for five days before denaturing. A suggested procedure is detailed within the guidance.

Staff who have symptoms of COVID-19 should stay at home and get tested as soon as possible. NHS England and Improvement confirmed in a letter to community pharmacies on 9 June 2020 that NHS staff “must self-isolate” for 14 days (reduced to 10 days from 14 December 2020) if the NHS test and trace service advises them to do so because they have come into close contact with a person with COVID-19. However, the letter adds that close contact “excludes circumstances where PPE is being worn”. If a member of the pharmacy team tests positive and there is a risk to the provision of pharmaceutical services then advice regarding the individual circumstances should be sought from the local Health Protection Team.

Staff who fall into one of the vulnerable groups at particular risk of complications from COVID-19 should not see patients face-to-face, regardless of whether the patient has possible COVID-19. Remote working should be prioritised for these staff.

NHS staff from a black, Asian or minority ethnic (BAME) background and others who who may be particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 — including those working in community pharmacies — should be risk assessed. In a letter dated 29 April 2020, NHS England said that “emerging UK and international data” suggest that people from BAME backgrounds are “being disproportionately affected by COVID-19”.

The Faculty of Occupational Medicine later published a risk reduction framework — backed by NHS England — to assist with the risk assessments on 14 May 2020. This was updated on 28 May 2020 to include guidance from the Health and Safety Executive to “help organisations identify who is at risk of harm”.

All NHS staff can access free wellbeing support and frontline health and care staff can access NHS volunteer responders support for themselves by calling 0808 196 3646.

What about ‘business as usual’ during the pandemic?

Pharmacies are on the frontline of the fight against coronavirus and demand for services is high. An updated standard operating procedure published on 27 October 2020 enables regional NHS England and NHS Improvement teams to notify pharmacies that they are able to adjust their opening hours to cope with increased demand. Pharmacies will be able to work behind closed doors for up to 2.5 hours a day before 10am, between 12 and 2pm or after 4pm.

A number of contractual services have been put on hold and others have been brought forward (see Learning article section ‘Adjusting opening hours and pharmacy services’ for further details). The Hepatitis C testing service in England will now launch on 1 September 2020 and the discharge medicines service is expected to start in February 2021.

During the first full lockdown in the spring of 2020, community pharmacies ensured that those who were shielding from COVID-19 (see Box 2) were able to receive their prescription medicines, either through friends and family, volunteers, or via pandemic delivery services but these were paused when cases dropped. The pandemic delivery service in England resumed for four weeks from 5 November 2020 to 3 December 2020, and again from 5 January 2021 to 31 March 2021, owing to sustained community transmission of COVID-19; it was expanded to patients told to self-isolate by NHS Test and Trace on 16 March 2021 until 30 June 2021. In Scotland, a pandemic delivery service started on 18 January 2021 and will continue until the end of March 2021.

Another new advanced service, distributing COVID-19 lateral flow test kits, was announced on 29 March 2021 for community pharmacies in England. Pharmacies will be able to earn up to £972 per week by providing the test kits to asymptomatic patients as part of NHS Test and Trace.

The need for patients to sign the back of prescription forms has been suspended until 30 June 2021 so as to reduce cross contamination and minimise handling of paperwork. Patients must still pay the prescription charge or prove their eligibility for exemption. Pharmacy staff should mark the relevant box for exempt patients and annotate all forms with COVID-19 in place of a signature.

Amendments to legislation to allow community pharmacies to close, with the permission of NHS England, “to focus on the delivery of flu or COVID-19 vaccinations” will come into effect on 9 November 2020 to allow for “flexible provision of immunisation services during the pandemic”. These changes follow the government’s decision to allow pharmacists to deliver unlicensed — in addition to licensed — vaccinations, such as a COVID-19 vaccine when one becomes available, with further work under way to expand the workforce able to deliver flu vaccines.

The amendments also allow community pharmacists in England to dispense COVID-19 treatments without a prescription under pandemic treatment protocols that will be issued by the government if a COVID-19 treatment became available that was suitable for distribution via community pharmacies and it was not found to be necessary for an authorised prescriber to decide to treat.

The General Pharmaceutical Council has stopped all routine inspections of pharmacies. Submission of revalidation records is postponed for registrants who were due to submit between 20 March 2020 and 31 August 2020, and requirements have been reduced for those due to submit between 1 September 2020 and 31 December 2020.

On 26 March 2020, the GPhC announced that the pharmacy registration assessments for June and September 2020 have been postponed. The GPhC confirmed on 30 November 2020 that online registration assessments would take place at centres around the UK on 17 and 18 March 2021.

More than 6,200 pharmacy professionals who left the register within the past three years have been given temporary registration so that they can to return to work during the COVID-19 pandemic, if they wish to do so. And in guidance published on 9 April 2020, final year pharmacy students were told they can join their arranged preregistration workplace ahead of the scheduled start date to help deal with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Will the government provide financial help during the pandemic?

The PSNC announced on 31 March 2020 that community pharmacies in England will be given cash advances totalling £300.0m over the next two months to help with cashflow during the pandemic, but no extra funding has been negotiated so far. Further advanced funding of £50m and

£20m at the end of May 2020 and June 2020, respectively, has since been announced by the PSNC. As with the £300m previously announced, the £70m is not additional funding and will be reconciled in 2020/2021.

Advance payments have also been agreed for community pharmacies in Scotland and Wales.

Additional funding of an initial £5.6m was agreed in Scotland on 7 April 2020 to support unparalleled levels of activity within community pharmacy during the pandemic. The funding will cover equipment costs, adaptations to premises, additional staffing and locum fees. Further additional funding of £4.5m for staffing costs for May and June 2020 was announced on 27 November 2020.

On 2 April 2020, the government announced that it had written off £13.4bn of debt as part of a major financial reset for NHS providers.

How can cross-infection be prevented?

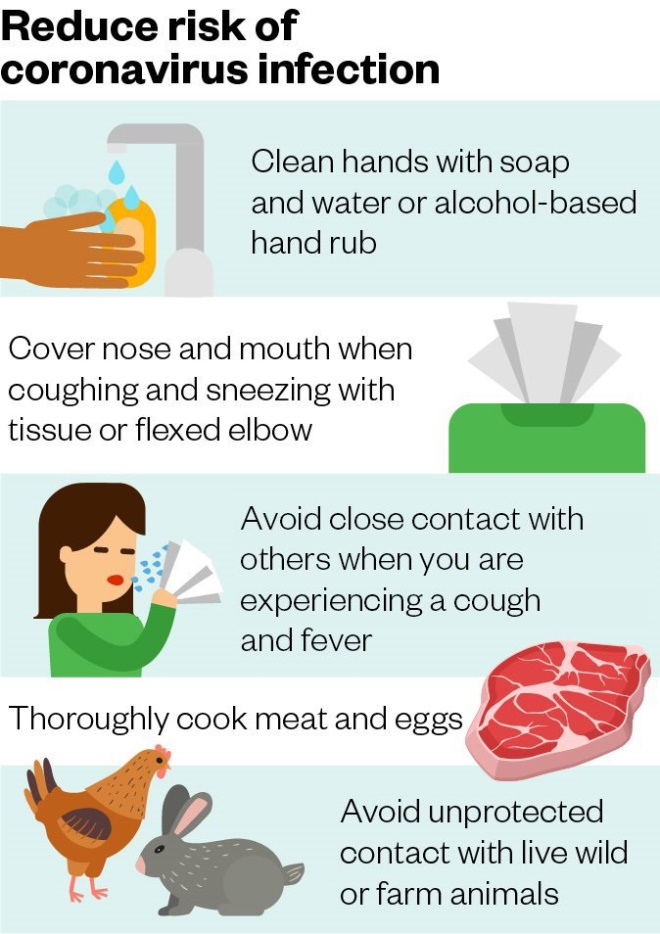

The WHO has created a range of infographics to illustrate how patients can protect themselves and others from getting sick; however, most of the advice is similar to what would be provided for colds and flu (see Figure)[24].

Figure: Infographic – How to reduce the risk of coronavirus infection

Source: Source: World Health Organization; 2020. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

There is no specific treatment for COVID-19. Although vaccines can be developed to treat viruses, owing to the novel nature of this infection, no vaccine has currently been developed and the process to develop one may take 12 to 18 months[18]. As an example, many antiviral agents have been identified to inhibit SARS in vitro, but there are currently no approved antiviral agents or vaccines available to tackle any potential SARS or SARS-like outbreaks, such as MERS or SARS-CoV-2[25].

There has been a lot of talk in the news and on social media about how certain medications can exacerbate the symptoms of COVID-19, what is the current advice around these medications?

On 16 March 2020, the British Cardiovascular Society and the British Society for Heart Failure published a statement saying that patients should continue treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers unless “specifically advised to stop by their medical team”.

The advice was issued following concerns circulated on social media that these medicines could predispose them to adverse outcomes should they become infected with COVID-19.

Both societies recommended that patients taking these medicines who present as unwell, or with a suspected or known COVID-19 infection, should be assessed on an individual basis and their medication managed according to established guidance. Inappropriate cessation of therapy could lead to a decline in control of blood pressure, heart failure or any other condition the individuals takes these medicines for.

Similar concerns have also arisen around the use of ibuprofen following unverified claims, backed by Oliver Veran, France’s health minister, that ibuprofen may exacerbate symptoms of the virus.

On 14 April 2020, the Committee of Human Medicines (CHM) — an advisory body of Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency — and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence both published reviews, which concluded that there is insufficient evidence to establish a link between use of ibuprofen, or other NSAIDs, and susceptibility to contracting COVID-19 or the worsening of its symptoms.

A rapid policy statement published by NHS England on the same date, highlighted that there had been some reports of possible adverse effects of the use of NSAIDs in acute respiratory tract infections more generally, which had led to suggestions to use paracetamol preferentially for fever/pain in such situations. However, it said that there was currently no evidence that the acute use of NSAIDs caused an increased risk of developing COVID-19 or of developing a more severe COVID-19 disease.

Where can I find information on managing COVID-19 patients?

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society has collated resources for hospital pharmacists on the clinical management of patients with COVID-19, including treatments, use of experimental therapies, and evidence-based summaries.

The resources also include information on critical care services during the pandemic and guidance on COVID-19 in special populations, such as children, pregnant women, patients taking warfarin and those with cancer, respiratory conditions, diabetes, rheumatological conditions and HIV.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has produced COVID-19 rapid guidelines covering a number of areas as well as rapid evidence summaries on COVID-19 treatments. NHS England and NHS Improvement has also published several specialty guides aimed at specialists working in hospitals during the pandemic. These resources have all been brought together on the NICE website.

NICE and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network are working with the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) to develop a guideline on the effects of long COVID on patients.

Is the coronavirus pandemic likely to precipitate medicines shortages?

The government banned the parallel export of chloroquine, as well as the antiretroviral lopinavir/ritonavir, on 26 February 2020 because they are being tested as possible treatments for COVID-19. There has been a lot of attention in the media on the potential benefits of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in treating patients with COVID-19 but the Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency has warned that these medicines are not licensed to treat COVID-19 related symptoms or prevent infection and, until there is clear, definitive evidence that these treatments are safe and effective for the treatment of COVID-19, they should only be used for this purpose within a clinical trial.

On 20 March 2020, the government banned from parallel export more than 80 medicines used to treat patients in intensive care units. The restrictions cover crucial medicines such as adrenaline, insulin, paracetamol and morphine and are designed to prevent medicines shortages. A further 52 medicines, including a number of respiratory medicines, antibiotics, analgesics and insulin products, were banned from export on 1 April 2020. And a further 33 medicines were banned from export on 24 April 2020, including further respiratory medicines and some drugs that are being trialled for COVID-19, such as azithromycin, dexamethasone, ruxolitinib, sarilumab and tocilizumab.

Community pharmacists have been experiencing huge demand for paracetamol and many have reported shortages of paracetamol tablets 500mg as pharmacy and general sales list packs. The National Pharmacy Association and the GPhC have both said that pharmacies are able to break down larger packs to prepare supplies of a non-prescription items for retail sale.

Shortages of Chiesi’s Clenil and Fostair inhalers, along with inhalers from other brands, have been noticed by pharmacists as patients begin to panic and order inhalers they potentially do not need. The wholesaler AAH Pharmaceuticals placed 11 inhalers on its “out of stock” list on the 30 March 2020. NHS England wrote to healthcare professionals working in primary care on 31 March 2020, asking them not to overprescribe or over-order during this time, as this will create further pressures on the supply chain.

Are there national clinical trials of potential drugs to treat COVID-19?

There are three major randomised controlled trials of medicines to treat COVID-19 being funded by the UK government: PRINCIPLE, RECOVERY and REMAP-CAP (see Feature and trials briefing), and several other trials are being nationally prioritised.

Preliminary results from the RECOVERY trial suggest that low-dose dexamethasone offers significant reductions in mortality for those patients with COVID-19 who require oxygen or ventilation, and it has been approved for use on the NHS.

Results from the REMAP-CAP trial have suggested that tocilizumab and sarilumab reduced the risk of death from COVID-19 by 24% when administered in the first 24 hours of a patient entering intensive care, and these drugs should now be considered by the NHS for hospitalised patients.

Results from the RECOVERY trial also suggest that tocilizumab reduces deaths in patients hospitalised with COVID-19.

An interim analysis of the PRINCIPLE trial suggests the corticosteroid budesonide shortens recovery time from COVID-19 by a median of three days, compared with usual care, in older people treated in the community.

In addition, on 28 April 2020, the Accelerating COVID-19 Research & Development (ACCORD) platform was launched, a collaboration between government, industry and research organisations that aims to reduce the time taken to set up clinical studies for new COVID therapies from months to weeks. ACCORD will rapidly test potential drugs through early stage clinical trials and, if they show promise, will feed them into the UK’s large-scale COVID-19 studies, such as RECOVERY. Bemcentinib, an AXL kinase inhibitor, will be the first to begin phase II studies across the UK within the next few days.

Further potential treatments will be rapidly fed into ACCORD as the programme rolls out over the next few weeks.

A Yellow Card website dedicated to reporting side-effects or incidents from medicines being used to treat COVID-19 has been set up by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

Is there a vaccine for COVID-19 and, if so, will pharmacy staff be involved in its roll out?

The UK has pre-ordered 357 million doses of different potential COVID-19 vaccines from seven manufacturers. The portfolio includes two adenoviral vector vaccines (Oxford/AstraZeneca and Janssen), two mRNA vaccines (BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna), an inactivated whole virus vaccine (Valneva), and two protein adjuvant vaccines (GSK/Sanofi, Novavax) (see feature).

Three of the vaccines being backed by the UK —BioNTech/Pfizer, Moderna and Oxford/AstraZeneca — released positive results from phase III trials in November 2020. The Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine was approved by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on 2 December 2020 and the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine was authorised for use by the MHRA on 30 December 2020 and the Moderna vaccine was authorised on 8 January 2021 (see feature).

Hospital pharmacists are overseeing ‘safe handling’ of COVID-19 vaccines in vaccination centres and hospital hubs as part of the mass vaccination programme, which started on 8 December 2020.

NHS England wrote to pharmacy contractors on 27 November 2020, saying that it is planning for designated pharmacy sites to be ready to administer COVID-19 vaccines under a local enhanced service from late December 2020 or early January 2021. However, “complex logistics” in the vaccine’s supply chain mean NHS England does not expect the majority of contractors’ sites will be able to meet a specific set of requirements, such as administering a minimum of 1,000 vaccines per week, with the fridge space, physical layout and staffing necessary to support that.

Community pharmacy contractors can also collaborate with their local primary care network to support them to deliver maximum vaccine uptake via the GP enhanced service or with vaccination centres, which started vaccinating patients on 14 December 2020.

Vaccination sites led by community pharmacies started administering COVID-19 vaccines to patients on 11 January 2021, with about 200 joining the first wave.

In a letter to contractors dated 16 February 2021, NHS England officials said it would reopen the application process to improve vaccination provision in a list of “priority locations”.

Community pharmacies able to administer up to 400 COVID-19 vaccines per week can now apply to become designated vaccination sites.

References

[1] BMJ Best Practice. 2020. Available at: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/3000165 (accessed January 2020)

[2] World Health Organization. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/ith/2020-24-01-outbreak-of-Pneumonia-caused-by-new-coronavirus/en/ (accessed January 2020)

[3] World Health Organization. 2020. Available at:https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports (accessed March 2020)

[4] Paules CI, Marston HD & Fauci AS. JAMA. 2020; In press. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0757

[5] Esper F, Ou Z & Huang YT. J Clin Virol. 2010;48(2):131–133. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2010.03.007

[6] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/symptoms.html (accessed January 2020)

[7] Otrompke J. Pharm J 2014;293:7833. doi: 10.1211/PJ.2014.20066890

[8] World Health Organization. 2004. Available at: https://www.who.int/ith/diseases/sars/en/ (accessed January 2020)

[9] World Health Organization. 2019. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ (accessed January 2020)

[10] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/sars/about/fs-sars.html (accessed January 2020)

[11] Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T et al. JAMA 2020. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565

[12] Ji W, Wang W, Zhao, X et al. J Med Virol 2020; In press. doi: 10.1002/fut.22099

[13] Callaway E & Cyranoski D. 2020. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-00180-8 (accessed January 2020)

[14] Banerjee A, Kulcsar K, Misra V et al. Viruses. 2019;11(1):41. doi:10.3390/v11010041

[15] Public Health England. 2020. Available at: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2020/01/23/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-what-you-need-to-know/ (accessed January 2020)

[16] Mahase E. BMJ 2020;368:m308. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m308

[17] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/about/transmission.html (accessed January 2020)

[18] World Health Organization. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/q-a-coronaviruses (accessed January 2020)

[19] World Health Organization. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/wuhan-virus-assay-v1991527e5122341d99287a1b17c111902.pdf?sfvrsn=d381fc88_2 (accessed January 2020)

[20] Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-action-plan (accessed March 2020)

[21] Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-on-social-distancing-and-for-vulnerable-people/guidance-on-social-distancing-for-everyone-in-the-uk-and-protecting-older-people-and-vulnerable-adults (accessed March 2020)

[22] Public Health England. 2020. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-stay-at-home-guidance/stay-at-home-guidance-for-households-with-possible-coronavirus-covid-19-infection (accessed March 2020).

[23] NHS England & NHS Improvement. 2020. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/covid-19-primary-care-sop-community-pharmacy-v1.pdf (accessed March 2020)

[24] World Health Organization. 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed March 2020)

[25] Adedeji AO & Sarafianos SG. Curr Opin Virol 2014;8:45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2014.06.002