Mclean

Monkeypox is caused by the monkeypox virus, an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus that is part of the orthopoxvirus genus, which also includes smallpox. Despite its name, which came from its initial discovery in monkeys in a Danish laboratory in 1958, monkeypox can infect various animals, including rope squirrels, tree squirrels, Gambian pouched rats and dormice.

Transmission is primarily through close contact with an infected animal, close or sexual contact with an infected person, or with materials contaminated with the virus (e.g. bed linen and towels).

How quickly is monkeypox spreading in the UK?

The first human case of monkeypox was identified in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1970, after which it became endemic across Central and West Africa. There were 558 suspected cases in Nigeria between 2017 and April 2022, during which time the virus was exported to several countries, including the United States, UK, Israel and Singapore.

However, in 2022, multiple cases of monkeypox began to be detected in non-endemic countries, including those in Europe, North America and Australasia, with a total of 25,864 cases in 80 countries that have not historically reported monkeypox as of 3 August 2022[1]. The first cases in the UK were identified on 6 May 2022 and, as of 2 August 2022, there were 2,759 highly probable and confirmed cases, with most of those being in England (see Figure 1)[2].

Almost three-quarters (73%) of cases in England are in London (see Figure 2).

What are the symptoms?

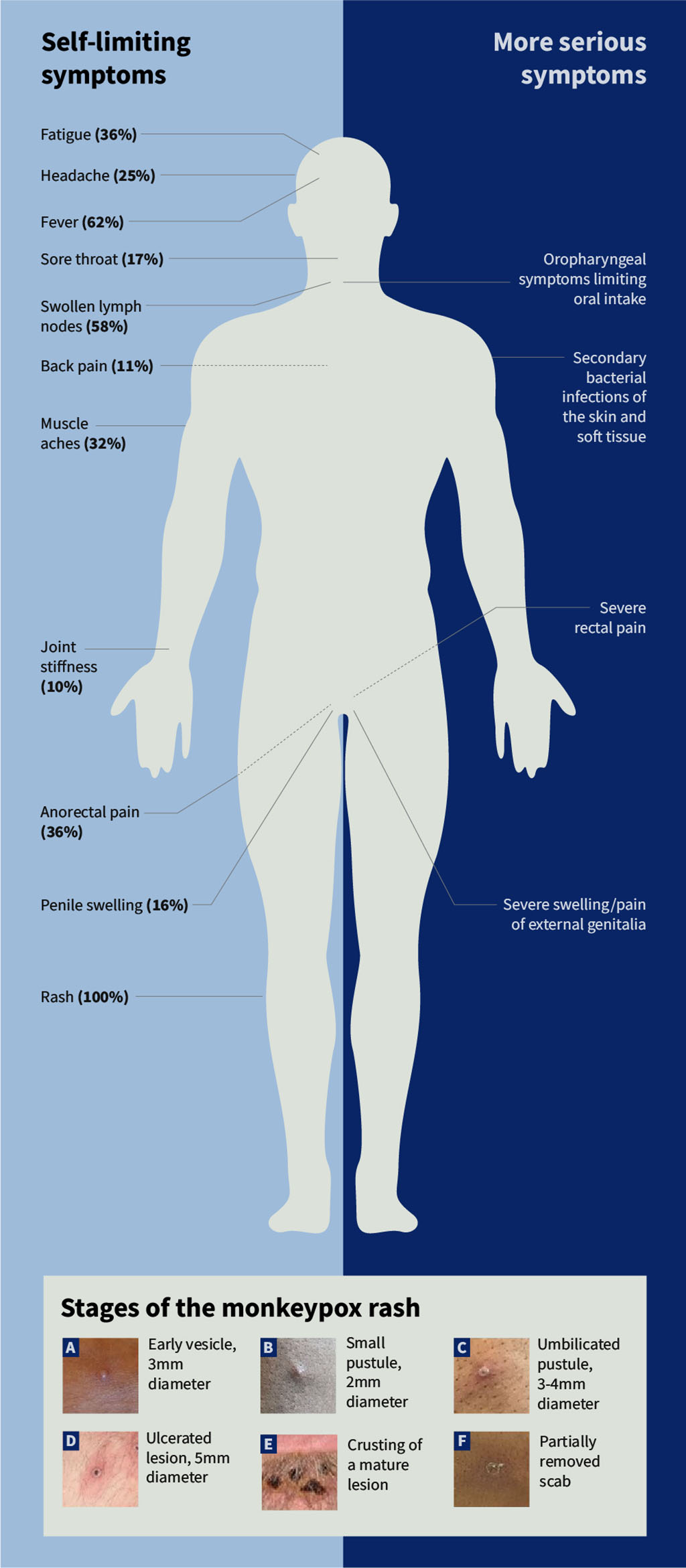

The incubation period for monkeypox can be 5–21 days following exposure, but is typically 6–13 days. Most symptoms are mild and self-limiting, with the prodromal phase lasting 1–5 days, followed by a second phase characterised by the appearance of a rash (see Figures 3)[3,4]. The rash generally starts at the site of inoculation, and spreads rapidly to other parts of the body, going from macules and papules to vesicles and pustules, which then crust over and fall off in 2–3 weeks. Lesions can occur on the oral mucous membranes, genitals, conjunctivae and cornea in some patients, and can be a single lesion or thousands of lesions.

Around 1 in 10 cases in the UK have received hospital care (this includes some cases unable to isolate at home)[5]. Patients admitted to hospital for clinical reasons have significant disease. There are no reported deaths so far in the UK, but several patients in European countries and those where the infection is not usually endemic have died.

Photographs: courtesy of the UK Health Security Agency

Who is most at risk of infection?

Anyone can catch monkeypox. However, as of 19 July 2022, 96.5% of cases in the UK have been in gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men and transmission continues to occur primarily within interconnected sexual networks (see Figure 4)[6].

There have been 13 cases in women and 1 in a child (aged under 16 years) in England as of 19 July 2022 (see Figure 5).

The case fatality of monkeypox depends on the virus clade, and it falls between 1% and 10% for the Central African clade and less than 3% for the West African clade[7]. The West African clade is currently circulating in the UK, with pregnant women, children and immunocompromised hosts being at highest risk of severe disease.

Box 1: What do I do if presented with a potential case?

Possible or probable cases should be tested for monkeypox. Patients should be advised to contact a sexual health clinic by telephone to make an appointment or call 111 for advice. Patients should stay at home and avoid close contact with other people until they have been assessed by the sexual health clinic and have received their results[8].

Possible case

A possible case is defined as anyone who fits one or more of the following criteria:

- A febrile prodrome compatible with monkeypox infection where there is known prior contact with a confirmed case in the 21 days before symptom onset

- An illness where the clinician has a suspicion of monkeypox — this could include unexplained genital, anogenital or oral lesion(s) (e.g. ulcers, nodules) or proctitis (e.g. anorectal pain, bleeding)

Probable case

A probable case is defined as anyone with an unexplained rash or lesion(s) on any part of their body (including genital/perianal, oral), or proctitis (e.g. anorectal pain, bleeding) and who:

- Has an epidemiological link to a confirmed, probable or highly probable case of monkeypox in the 21 days before symptom onset OR

- Identifies as a gay, bisexual or other man who has sex with men OR

- Has had one or more new sexual partners in the 21 days before symptom onset OR

- Reports a travel history to West or Central Africa in the 21 days before symptom onset

What is the treatment?

Treatment for monkeypox is generally supportive (e.g. pain relief, keeping hydrated, etc.). However, antivirals may be used for more severe cases, or for people who are at risk of severe disease[9].

In July 2022, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency approved tecovirimat, an antiviral drug that works against orthopoxviruses, including smallpox, cowpox and monkeypox, for adults and children who weigh at least 13kg[10].

Tecovirimat has not been studied in human efficacy trials for monkeypox, although it has demonstrated efficacy against orthopoxviruses (including monkeypox) in animal models, and there are pharmacokinetic and safety data in humans[11].

Tecovirimat inhibits the activity of the VP37 envelope protein, which is encoded by a highly conserved gene in all members of the orthopoxvirus genus; this stops the virus from leaving the infected cell, therefore slowing spread of the infection.

The National Institute for Health Research has commissioned a phase II study to investigate the efficacy of tecovirimat for the management of monkeypox in non-hospitalised patients[12].

Can it be prevented?

The UK Health Security Agency has ordered more than 100,000 doses of the third-generation smallpox vaccine Imvanex (MVA-BN; Bavarian Nordic), which is approved in the UK for prevention of smallpox and can be used for monkeypox. However, global supplies are limited and supplies will become available as each batch is manufactured. To begin with, only one dose of vaccine will be offered, with a second dose offered if the outbreak continues and more vaccine becomes available.

Imvanex contains a replication defective virus and should be considered as an inactivated vaccine.

Vaccination is being offered at specialist sexual health clinics to those most at risk (see Figure 6).

Box 2: Vaccination schedule

Pre-exposure vaccination:

- Two doses, 28 days apart for individuals previously not vaccinated against smallpox (smallpox vaccines were only used up to 1970s);

- A single dose for individuals previously vaccinated against smallpox.

Post-exposure vaccination:

- A single dose, preferably within 4 days of exposure but can be given up to 14 days after exposure in those at ongoing risk, or those who are at higher risk of the complications of monkeypox.

Booster:

- A booster dose can be given at least two years after the primary course if the individual is at ongoing risk[13].

- 12022 Monkeypox Outbreak Global Map. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2022.https://www.cdc.gov/poxvirus/monkeypox/response/2022/world-map.html (accessed 4 Aug 2022).

- 2UK Health Security Agency. Monkeypox outbreak: epidemiological overview, 29 July 2022. Gov.uk. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-outbreak-epidemiological-overview/monkeypox-outbreak-epidemiological-overview-29-july-2022 (accessed 4 Aug 2022).

- 3Factsheet for health professionals on monkeypox. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2022.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/all-topics-z/monkeypox/factsheet-health-professionals (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 4Patel A, Bilinska J, Tam JCH, et al. Clinical features and novel presentations of human monkeypox in a central London centre during the 2022 outbreak: descriptive case series. BMJ. 2022;:e072410. doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-072410

- 5UK Health Security Agency. Investigation into monkeypox outbreak in England: technical briefing 3. Gov.uk. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-outbreak-technical-briefings/investigation-into-monkeypox-outbreak-in-england-technical-briefing-3 (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 6UK Health Security Agency. Investigation into monkeypox outbreak in England: technical briefing 4. Gov.uk. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-outbreak-technical-briefings/investigation-into-monkeypox-outbreak-in-england-technical-briefing-4 (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 7Adler H, Gould S, Hine P, et al. Clinical features and management of human monkeypox: a retrospective observational study in the UK. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022;22:1153–62. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00228-6

- 8UK Health Security Agency. Monkeypox: case definitions. Gov.uk. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/monkeypox-case-definitions (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 9UK Health Security Agency. Monkeypox: background information. Gov.uk. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/guidance/monkeypox#treatment (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 10SIGA Technologies Receives Approval from UK for TecovirimatTreatment Approved for Smallpox, Monkeypox, Cowpox, and Vaccinia Complications. BioSpace. 2022.https://www.biospace.com/article/releases/siga-technologies-receives-approval-from-uk-for-tecovirimattreatment-approved-for-smallpox-monkeypox-cowpox-and-vaccinia-complications (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 11Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, et al. Oral Tecovirimat for the Treatment of Smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:44–53. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1705688

- 12Efficacy of Tecovirimat for the treatment of non-hospitalised patients with confirmed monkeypox – research brief. National Institute for Health and Care Research. 2022.https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/efficacy-of-tecovirimat-for-the-treatment-of-non-hospitalised-patients-with-confirmed-monkeypox-research-brief/30705 (accessed 2 Aug 2022).

- 13UK Health Security Agency. Monkeypox vaccination recommendations. Gov.uk. 2022.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/monkeypox-vaccination (accessed 3 Aug 2022).

You may also be interested in

Everything you need to know about mpox

Norovirus and strategies for infection control