Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

Developing “adaptable pharmacists” and “proficient prescribers” who are confident and capable of working in multidisciplinary teams across healthcare settings from the start of their careers — this was the goal set by the General Pharmaceutical Council in its 2021 standards for the initial education and training of pharmacists.

To meet these new standards, clinical placements for pharmacy students are being extended and enriched. Students are spending more time on placements, learning in all sectors of practice and moving from observing tasks to carrying them out.

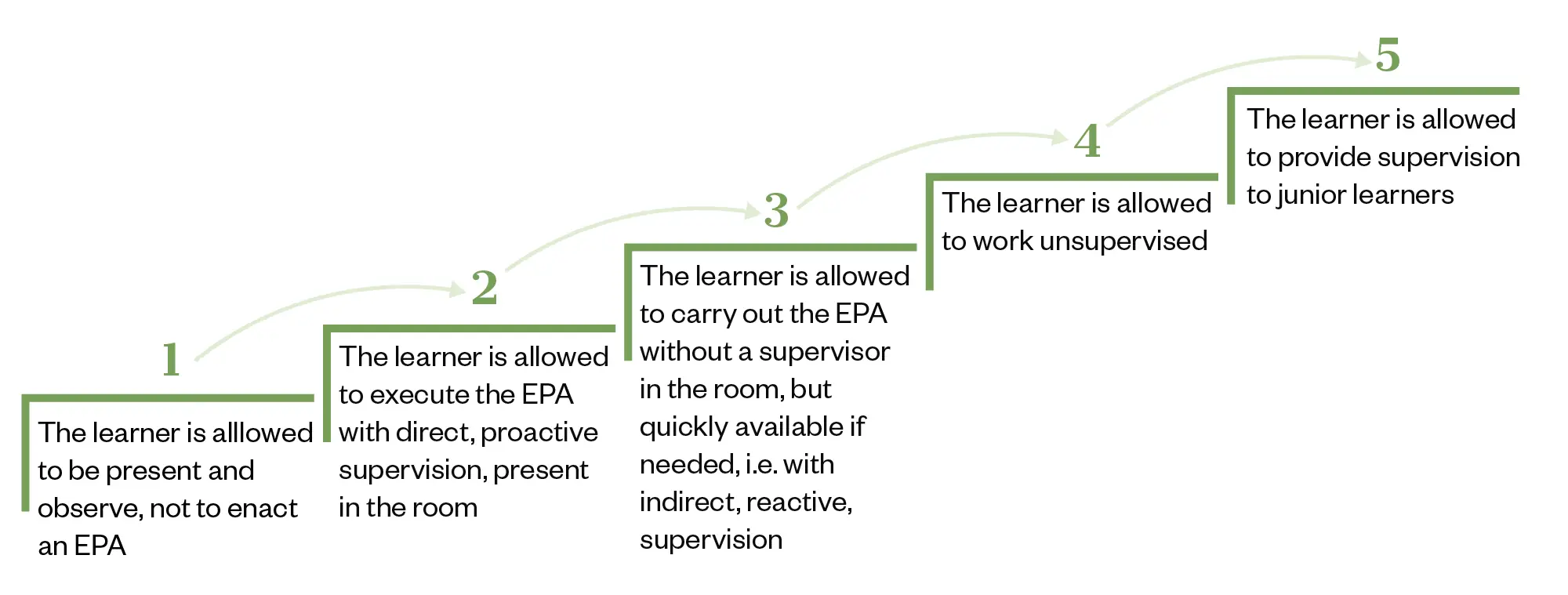

There have been pilots to test how these expanded placements will work and what “entrustable professional activities” (EPAs) students should be doing while spending time in community, hospital and GP pharmacy services. EPAs are activities that students can be entrusted to carry out with appropriate supervision (see Figure).

Across England, Scotland and Wales, the differing population sizes and service offerings have meant that the approach to placements has been markedly distinct.

In England, there is no target set for time spent on placements, with the only guidance being that it should be “significant”, says Katie Maddock, head of the School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering at Keele University and chair of the Pharmacy Schools Council.

In Wales and Scotland, universities are working towards a goal of 11 weeks on placement over the 4-year MPharm course and are currently at 9 weeks. The incremental increase is to make sure there is enough capacity in the system and to review how placements are working.

Funding and oversight also differ between England, Scotland and Wales, and each country has its own list of EPAs.

The level of entrustment increases as the level of supervision decreases

The Pharmaceutical Journal

Lack of funding

Undergraduate pharmacy clinical placements were included in the ‘Education and Training Tariff for England’ for the first time in September 2022, which means that employers providing MPharm placements now receive nationally standardised funding at £5,343 per full-time equivalent (see Box). The funding is intended to cover the direct costs involved in delivering the placements; for example, staff teaching time, administration costs, and educational supervisors and assessors.

Box: Funding across the three nations

England

Education and training tariffs are set by the Department of Health and Social Care. Pharmacy students are eligible for the clinical tariff, which is £5,343 plus the market forces factor (MFF), which accounts for a difference in regional costs, per full-time equivalent, which is 40.8 weeks of placement activity. A week should be reflective of 37.5 hours of placement activity. Simulation-based learning is included.

Wales

Under the Funded Pharmacy Undergraduate Placement Programme, host sites receive £120 per day per student, provided by the Welsh government.

Scotland

Pharmacy ‘Additional Cost of Teaching’ fees are available from the Scottish government for training providers that are facilitating placements and have committed to undertaking Preparation for Facilitating Experiential Learning Training. The amount received in Scotland is generally closer to the Welsh payment but is “prone to variation as it is an allocation model”, according to a spokesperson for NHS Education for Scotland. The funding covers payment for placements, facilitator training and student expenses, they add.

However, with £32,552 per year on offer for taking on a medical undergraduate, Maddock believes the stark difference between the amount of funding could threaten the number of primary care pharmacy placements.

Primary care network pharmacists are very keen to host MPharm students, but as soon as they run it past their practice manager, that puts the block on

Katie Maddock, head of the School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering, Keele University, and chair of the Pharmacy Schools Council

“Primary care network pharmacists are very keen [to host MPharm students], but as soon as they run it past their practice manager, that puts the block on. We will get there, we’re just finding it hard to break into,” she says.

Using development funding from NHS England, the School of Pharmacy at the University of Bradford is doing a project to grow the number of general practice placements available to its students. “We’re quite hopeful we’ll be able to offer [placements to] a whole year group next year,” says Jonathan Silcock, associate professor in pharmacy practice at the university. The school is also considering different types of experience, including in care homes and community services, he adds.

The funding for pharmacy placement providers in England is also far less than that received in Scotland and Wales.

Sam Chidlow, policy and programmes manager at the Company Chemists’ Association (CCA), says the lower funding for providers in England prevents community pharmacy multiples from offering as many placements as they would like, adding that the CCA has calculated that pharmacies receive about £20 per day per student in England, compared with £120 in Wales and £150 in Scotland.

I would suspect there are significantly more places offered by CCA members in Wales and Scotland where it is funded better

Sam Chidlow, policy and programmes manager at the Company Chemists’ Association

“I would suspect there are significantly more places offered by CCA members in those places where it is funded [better],” he says.

Khalid Khan is head of training and professional standards at Imaan Healthcare, a regional community pharmacy chain with about 70 branches, mainly throughout the M6 corridor and Yorkshire. The company works closely with four schools of pharmacy to provide placements. Khan says that Imaan Healthcare is keen to offer placements because it is good for the profession, but the funding is “almost negligible”.

“We have stressed to the universities to please just minimise the [administrative] burden on our teams because there’s very little capacity in community pharmacy. They have to make this as painless as possible.”

Hospitals in England also have concerns about the tariff not being enough to pay for pharmacists’ time, says Maddock. “We have reassured [them] that it does not have to be pharmacists [who supervise the students] and, while [universities] all have different models about how placements are happening, secondary care is starting to settle into it.”

Richard Draper, advanced specialist pharmacist at University Hospitals of North Midlands NHS Trust, has been involved with Keele University from the pilot stage of the new style of placements in 2021/2022.

The trust now offers 50 places to Keele students across two sites. Keele University has also funded a pharmacy technician at the trust — Hayley Wilson — to lead on placements. “We were finding on the wards that [the students] didn’t have much drug history experience so we are running workshops [at the university] in the second year before they come to us in year three. We guide them through it and build their confidence,” explains Wilson, who organises how the placements work at the hospital.

Draper says: “We’ve got at least six schools of pharmacy across the Midlands. That’s thousands of students needing placements, so taking two or three students isn’t good enough. I’m convinced of scale because that’s what is needed but also that’s the only way to get a meaningful tariff generation.”

Pharmacy students in England are also not eligible for the NHS learning support fund, which is available to other healthcare students studying in England and offers £5,000 per academic year to pay for travel and temporary accommodation costs while on clinical placements.

“As the pharmacy degree has evolved to include a greater emphasis on clinical practice, pharmacy schools are delivering a growing number of clinical placements across a range of care settings and geographies. It seems more and more unjust that pharmacy students are excluded from the financial support they deserve to attend these placements,” says James Davies, director for England at the Royal Pharmaceutical Society.

Lack of guidance

The lack of guidance on placements from NHS England has been frustrating, says Draper, and that is why universities are all doing things slightly differently. “If we didn’t have Hayley, we would be finding this really difficult, and that’s where scale comes in, because it provides more funding.”

There is a workforce crisis for pharmacists, and then that has a knock-on effect to what people feel that they can offer

Michelle Elston, head of professional experience at the School of Pharmacy at Aston University

Michelle Elston, head of professional experience at the School of Pharmacy at Aston University, agrees that it has been left up to schools to interpret what placements should look like, adding that it has been a major piece of work.

“We can’t send 160 [students] in a year group to one place on one day. We’ve got to fit that into our timetable. We’ve got to work with employers and providers to what they can feasibly do. There is a workforce crisis for pharmacists, and then that has a knock-on effect to what people feel that they can offer,” she explains.

Aston University aims for four-week blocks of placements at the end of second and third years, but that has come with capacity headaches in community pharmacy, owing to the number of providers needed, and hospital pharmacy, because of staffing.

Natalie Lewis, associate head (operations) for the School of Pharmacy at Aston University, adds that it will be vital to evaluate the new style placements, particularly around whether quality is being maintained. “Everyone is doing something really different, and it’d be really good at some point to share and learn how other people are tracking it.”

Silcock says the University of Bradford is aiming for a more even spread of three weeks of placements per year, across the sectors. “Hospitals prefer longer placements, but they also prefer to have fewer people, so there are some conflicts that we haven’t completely resolved.”

A national contract

Another aspect causing difficulties for large community pharmacy multiples in England is the lack of a national contract setting out the terms of the placement, says Maddock.

“Boots is potentially working with 32 schools of pharmacy, that’s 32 [service level agreements], 32 legal departments to deal with,” says Maddock.

“I know it would appreciate something like the education contract that secondary care and primary care have got, because that means the contracting element comes from NHS England rather than individual schools,” she adds.

Chidlow agrees that a national contract would be helpful. “We think there’s probably a bit more of a role for NHS England in setting out a standardised approach. At the moment, it seems relatively burdensome.”

The NHS Education Contract between NHS England and education and placement providers details the framework for responsibilities and enables NHS-managed sector organisations, such as hospitals, to be paid in response to healthcare student placement activity data submitted by universities. However, community pharmacies are currently paid directly by universities. According to NHS England, a future iteration of the NHS Education Contract is currently being developed and how contracting might work for community pharmacy is being considered as part of this.

NHS England declined to comment further on the opportunities and challenges that the new clinical placements have brought for universities and providers.

A team approach

In Scotland, the growth of experiential learning began in 2018/2019 as a collaboration between NHS Education for Scotland (NES), the schools of pharmacy at Robert Gordon University and the University of Strathclyde, and health boards.

‘Additional Cost of Teaching’ funding from the Scottish government provides payment for placements and training for a pharmacist facilitator, as well as supporting student financial costs, since the 1,000 pharmacy students across Scotland can be sent anywhere in the country for placement.

It is very much a team approach, explains Ailsa Power, NES associate postgraduate pharmacy dean. In 2023, detailed frameworks were published to outline EPAs that students on placements should carry out under supervision, which build in complexity as they progress.

Craig McDonald, lecturer in pharmacy practice and placement officer at Robert Gordon University, says placements build from one week in community pharmacy in the first year of the MPharm to four weeks across all sectors by the final year. The offering is the same for the University of Strathclyde to minimise the impact on providers, with the placements organised and quality assessed by NES.

“We need to give a breadth of experience in different settings and in different locations,” says McDonald. “The frameworks are not exhaustive but a suggested list of items to be covered that are appropriate for students in different stages.”

Each facilitator will give individual feedback on the student and their placement experience

Ailsa Power, NHS Education for Scotland associate postgraduate pharmacy dean

Paul Kearns, teaching Fellow in experiential learning at the University of Strathclyde, adds that universities keep adapting. “We get facilitators [from the providers] in over the summer each year, and we look at what activities students can do and build that into our handbooks. In advance of placements, facilitators get in touch with students and check their level of experience so they can tailor activities.”

High standards of facilitation of learning and development are expected, explains Power. “Each facilitator will give individual feedback on the student and their placement experience.”

Hospital has been the most challenging sector in terms of capacity, partly because there are fewer large acute hospitals, says Power. “We’re currently looking to see if community services could take on more of it.” Some placements already take place within community mental health or drug addiction services, she adds.

“As a team, the focus has been on the quality of the placements provided rather than the number of weeks,” says McDonald.

“We get data from students after each placement. We’re collecting a lot of intelligence on placement sites,” adds Power. “If there’s any issues, we will contact them and go through an action plan if they still want to be a provider.”

Roisin Kavanagh, director of pharmacy at NHS Ayrshire and Arran health board, says that, over time, providers have gained a better understanding of what the students are able to do at different stages and try to avoid repetition. “We are looking at a passport for the students so they can show what they have done and get a broad experience.”

Improving capacity

Wales is taking a similar approach to Scotland in that Health Education and Improvement Wales (HEIW) and the two schools of pharmacy at Cardiff University and Swansea University (a new MPharm course at Bangor University is currently being accredited) have come together to plan placements. HEIW takes expressions of interest and quality manages the placements, as well as providing supervisor training.

The schools have now reached 40 days of placement over the 4-year degree, with a goal to move to 55 days over the next year or two, explains Renata Poole, HEIW pharmacy clinical placement lead. It started with a pilot with Cardiff University, predominantly in community pharmacy, with several placements in hospital and GP sites. The evaluation of students — there are around 750 in Wales — and provider feedback has informed future plans and is ongoing. Students across the country have the same placement workbook and expectations are set nationally.

In the 2023/2024 academic year, every third- and fourth-year student has spent at least one week in each sector. “It’s a good position to be in and students are getting a variable experience, which we want to continue,” explains Robert James, lecturer in pharmacy practice and academic placement lead at Cardiff University.

“Although, last year, we initially had limited places in hospital and GP, now that the word is getting out, capacity is improving quite a bit in both,” he adds.

Wales too has been looking into more specialist and community sectors for a breadth of experience on placement. “We have had students go into mental health hospitals, for example,” says Simon Wilkins, associate professor in pharmacy at Swansea University. “They can achieve the EPAs in various sectors and the feedback has been that have had some really good supervision and experience.”

The list of EPAs that has been set out in Wales is purposely broad and has six categories that can be used across sectors: patient history taking; responding to patient queries/signs/symptoms; medicines reviews; clinical checking; patient counselling; and lifestyle optimisation.

Pros and cons

There are pros and cons to the different approaches being taken in each of the home nations, says Maddock. In England, there is more freedom for schools of pharmacy to develop a placement offer that works for their students, which might include more time in one place or more weeks on placements. But, with smaller systems, it has been easier for Scotland and Wales to coordinate and oversee placements, she adds.

There will never be a national placement system in England, I know the providers want it but it’s never going to happen

Katie Maddock, head of the School of Pharmacy and Bioengineering, Keele University, and chair of the Pharmacy Schools Council

However, she emphasises that schools of pharmacy in England have robust mechanisms for checking quality and hold regular regional meetings. “There will never be a national placement system [in England], I know the providers want it but it’s never going to happen. But we are working towards common documentation and we’re also waiting for the EPA toolkit to come out, which I think placement providers will be very grateful for.”

It will take the first cohort of graduates who have been through placements with EPAs to really embed them, Maddock says. “It is a culture shift — they should be interacting with other healthcare professionals, they should be putting themselves forward and asking for things to do, and that has been the knottiest problem for students and providers.”

For more information on entrustable professional activities, see the following resource from The Pharmaceutical Journal:

3 comments

You must be logged in to post a comment.

CTMUHB is the provider of the most clinical placements in the UK. We have a model that can be used to scale placements for other acute and community hospital sites. We are also looking at how to deliver GP and Prison placements, as part of our health boards offer. A chance to share and discuss this on a national level would be a great opportunity for other teams across the UK. My feeling, having delivered nearly 6 months worth of placements, for over 250 students, is that the model is not dependent on high levels of funding, though will increase provider will to undertake. A change in the culture in pharmacy education is a critical success factor, as well as working in partnership with local HEIs, clinical education colleagues. Strong leadership of the placements is essential, and the attitude of "it's too much work" is a risk to the future sustainability of the pharmacy professions development and ability to come out as prescribers in 2026.

I'd agree with Rhian that culture is as big a barrier as funding. In large organisations this funding can also get lost and not directly reach pharmacy teams. Very happy for you to talk to our placement development group in West Yorkshire ICS and Yorkshire & the Humber. The local HEIs and providers (of all sorts) are trying to understand each other's needs and capabilities.

Happy too, it's my passion! Send me an email on rhian.carta@wales.nhs.uk