Wes Mountain/The Pharmaceutical Journal

Responses to a survey carried out by the British Oncology Pharmacy Association (BOPA) on the state of anticancer therapy provision in the UK make for difficult reading[1].

One anonymous respondent to the survey of NHS trusts, published in September 2022, reported repeated delays to cancer treatment for a patient aged 21 years with Hodgkin’s lymphoma because the medicine he needed was not delivered on time by the private aseptic unit contracted to prepare it. With his first three treatments all delayed, “it affected his morale so much”, the respondent said.

“Every time he had to have a few days to gather himself to receive treatment again.”

Of the survey’s 69 responses, 91% said patients were experiencing delays to their cancer treatment, where they had to wait more than 60 minutes from their appointment time[1]. Of these, 45% said these delays happen monthly, 27% said weekly, and 16% said they were a daily occurrence.

Respondents reported various reasons for the delays: 69% said they were caused by late deliveries of systemic anticancer therapies (SACT) from commercial compounders, while 62% said they were caused by delays in preparing SACT within pharmacy aseptic units[1].

Both issues are the result of ongoing and worsening capacity issues within aseptic services. A problem that shows no signs of slowing despite repeated calls to the government for help.

Cancer learning ‘hub’

Pharmacists are playing an increasingly important role in supporting patients with cancer, working within multidisciplinary teams and improving outcomes.

However, in a rapidly evolving field with numbers of new cancer medicines is increasing and the potential for adverse effects, it is now more important than ever for pharmacists to have a solid understanding of the principles of cancer biology, its diagnosis and approaches to treatment and prevention.

This new collection of cancer content, brought to you in partnership with BeOne Medicines, provides access to educational resources that support professional development for improved patient

Increase in demand

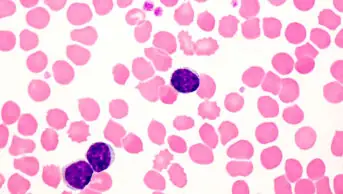

SACT are any drug treatment used to control or treat cancer, including chemotherapy, immunotherapy, targeted therapy, hormonal therapy or a combination of these[2].

A growing number of cancer patients are relying on SACT for treatment. According to NHS CancerData, SACT administrations increased by 90,000 in 2022 compared with 2021, around 400,000 higher than in 2020[3].

In England, it is reported that nearly 3.5 million doses of SACT were delivered from April 2021 to March 2022, estimated to be increasing at a rate of 6–8% per year[3].

This growth in demand is largely owing to increasing numbers of patients living with advanced cancer on maintenance therapies and new treatment options becoming available.

The demand for these products has increased hugely and it’s impossible for anyone to keep up with that

Emma Foreman, consultant pharmacist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and vice chair of the British Oncology Pharmacy Association

“The number of different cancer treatments available has increased, there are new drugs available every year, and patients are living longer,” says Emma Foreman, consultant pharmacist at The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and vice chair of BOPA.

Latest data from Cancer Research UK (2017–2019) reveal that there are around 167,000 cancer deaths in the UK each year. The mortality rates for all cancers combined have decreased by 10% over the past decade, and this is projected to fall by another 6% within the next 15 years[4].

Since 2000, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has made 523 individual recommendations on cancer drugs across 453 technology appraisals, 78% of which have been positive recommendations for use [5]. More than 200 technology appraisals have been published in the past five years alone and, with several cancer drugs currently being assessed by NICE, it is inevitable that more will be approved in the future (see Figure)[5].

While these figures are excellent news for cancer patients, it has put enormous pressure on the shrinking oncology workforce.

“The demand for these products has increased hugely and it’s impossible for anyone to keep up with that,” adds Foreman.

Strain on workforce

In May 2023, BOPA and other cancer organisations wrote to then health minister Steve Barclay to highlight their struggles with meeting rising demand for services without equivalent investment or support for the oncology workforce[6].

“To meet this increased demand, oncology teams are having to create capacity in ways which compromise patient safety and quality of care and increase pressure on already overworked staff,” it said.

BOPA’s survey revealed vacancy rates of 20.6% (176/854) in technical services staff and 19.0% (135/711) in clinical services staff across the 69 respondents — 31.7% and 16.6% of these vacancies, respectively, had been advertised at least once without successful recruitment[1].

Foreman, who co-authored the report, explains that there are fewer and fewer pharmacists and technicians coming through with technical skills, just when they are needed the most.

“The pharmacy degree is getting more and more clinical, and the focus is more on this advanced practitioner pathway where we become prescribers and spend more time face to face with patients.

“Rightly so, but it does mean that our formulations skills, technical services skills and preparation skills — they’re falling by the wayside,” she says.

People with cancer continue to face unacceptable delays for vital diagnosis and treatment in every part of the UK

Matt Sample, health policy manager at Cancer Research UK

Foreman adds that a lot of experience is being lost at the other end of the spectrum, with many supervising pharmacists and quality assurance pharmacists retiring.

“There simply isn’t enough capacity, both in terms of staff and equipment, to meet the rising demand. This includes pharmacy services, which play a vital role in cancer treatment,” says Matt Sample, health policy manager at Cancer Research UK.

“Despite the tireless work of staff across the health system, [people with cancer] continue to face unacceptable delays for vital diagnosis and treatment in every part of the UK,” he adds.

“The UK government must show leadership and ensure that every part of the cancer pathway has the resources it needs to offer patients the timely, quality care they deserve.”

Reliance on private providers

To continue meeting the growing demand for SACT, NHS trusts are having to rely heavily on commercial compounders. Almost three-quarters (74%) of respondents to the BOPA survey said they use a mixture of in-house preparations and outsourcing to commercial compounders and 16% said they rely entirely on commercial compounders, leaving only 10% of trusts being able to prepare all IV SACT in house[1].

This reliance on commercial compounders can cause problems for patients.

“When it comes to commercial manufacturers, sometimes they are punctual with the order and sometimes not,” says James Cheung, specialist pharmacist, aseptic services at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

“[People with cancer] have a very tight timeframe to start therapy once diagnosed and for our day unit, we have around 40 to 50 patients per day.

“So, we want these orders [from commercial compounders] because they are straightforward to dispense and patients don’t have to wait too long for their dose. But they are unreliable,” he adds.

According to the BOPA survey, 76% of respondents reported that patients had to reschedule their treatment to a different day at least once in the past six months. The most common reasons being supply issues (67%), followed by aseptic unit capacity issues (35%) and staffing issues (33%)[1].

“One respondent to our survey wrote about a patient who had their dose of cetuximab delayed three times in a row because their commercial compounder could not provide the dose for them,” says Foreman, highlighting that delays seem “to be worse with the people that are reliant on these third-party providers”.

“Sometimes you don’t even know there was an issue with the order until it doesn’t turn up. We always have to call the customer service [department] just to find out what is happening,” says Cheung.

“[Commercial compounders] might have reduced capacity, but sometimes orders are delayed a month. That’s a long time.”

BOPA’s letter to the health secretary notes “that for each month a patient is delayed from starting treatment, the risk of death increases by around 10%”, before adding that “these types of waits are now sadly routine”[6].

Nearly all (98%) respondents procuring SACT from commercial compounders said that they had experienced delays in receiving orders, 51% had orders cancelled and 47% had orders changed[1].

However, the British Specialist Nutrition Association (BSNA), which represents independent aseptic compounders, says its members are not aware of any instances where patients have not been able to access treatment.

Declan O’Brien, director general of BSNA, highlights that the BOPA survey reports instances where respondents have recorded products from aseptic manufacturers as not being available or being delayed. “This is a ‘catch all’ concept that covers many issues from ordering practices, such as late ordering or ordering out of contract, rescheduling of patients, to the impact of product volume caps on aseptic manufacturers,” he says.

“It also reflects a shortage in the supply of important drugs, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). There are currently approximately 40 APIs in scarce supply for the NHS, as well as aseptic manufacturers.”

Joseph Williams, a specialist cancer pharmacist at the Christie NHS Foundation Trust and chair of BOPA, explains that the Christie has started to use closed systems at ward level and in patient homes to try to relieve the pressure on commercial compounders and improve patient care.

Closed system drug-transfer devices enable certain cancer drugs to be compounded outside of aseptic units by mechanically prohibiting environmental contaminants from entering the system and preventing hazardous drugs or vapour from escaping[7].

While this provides a temporary relief to aseptic service capacity, Williams and Foreman stress that it is only shifting the workload from pharmacy to nurses. “It’s a short-term solution but it’s not the end-goal,” Foreman states.

O’Brien agrees. Moving more preparation currently compounded by aseptic facilities back to the ward for nurses to undertake “should be of concern to everyone, including patients, due to the increasing time pressure on nurses”, he says, adding that it runs counter to the 2020 Carter report on transforming NHS pharmacy aseptic services in England, which aimed to free up 4,000 nurse full time equivalents[8].

Financial cost

The move towards outsourcing aseptic services as a solution to the workforce pressures is also coming at a heavy financial cost.

Over the past five years, there have been several commercial contracts up for tender for aseptic manufacturing of medicines for the NHS, ranging from £1.5m to £200m[9]. The highest contract, at £3.5bn (over two years), was submitted by University Hospitals of Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust in 2022 for aseptic manufacture and supply of ‘ready-to-administer’ anticancer chemotherapy drugs in accordance with the national dose banding standards, with an option to extend for a further two years.

A search of the government’s contract finder website for contracts relating to aseptically prepared chemotherapy and parenteral nutrition by The Pharmaceutical Journal found 12 tenders for contracts covering April 2021 to July 2035, worth a total of £4.19bn — an average cost of £185m per year per contract[9].

Many NHS trusts are also using private companies for clean room services, home delivery services and upkeep of their aseptic units, which can cost millions of pounds per year[8].

From 2023/2024, NHS England is reverting to pre-COVID funding arrangements, whereby funding is based on the volume of treatment delivered[10].

This has raised concerns among oncology departments because “if capacity issues are preventing treatments from being delivered, this may result in a reduction in annual funding”, a policy briefing published by the Royal College of Radiologists in May 2023 on SACT capacity issues states.

“In addition, by setting the departmental budget based on past activity, future budgets will not account for the increasing rate of SACT delivery,” it adds [10].

A combination of these financial and workforce factors have forced some aseptic facilities to shut down, further adding to the ‘perfect storm’ of problems[1].

In October 2023, The Pharmaceutical Journal asked NHS England for the number of aseptic facilities that had shut down in England over the past five years via a freedom of information request. On 15 November 2023, NHS England replied: “Neither NHS England nor Specialist Pharmacy Services are required to keep records of unit closures, however we believe there have been around 10 unit closures over the last few years. Some of these units may reopen.”

There are currently 129 NHS aseptic units (excluding radiopharmacies) on the NHS Specialist Pharmacy Service quality assurance audit list, according to NHS England.

NHS intervention — pathfinder hubs

Limited service capacity means many oncology departments are having to make difficult decisions over whether to withhold access to approved treatments or prioritise which patients receive treatment within a safe timeframe[10].

To mitigate these issues, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) announced in June 2023 the development of five “pathfinder” aseptic hub facilities to open across England by 2026/2027.

We’re establishing a network of regional hubs, which will be Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency authorised to prepare and supply aseptic medicines across a large area

Sue Ladds, hospital pharmacy modernisation lead at NHS England

Speaking at an NHS Benchmarking Network webinar in October 2023, Sue Ladds, hospital pharmacy modernisation lead at NHS England, explained: “We’re establishing a network of regional hubs, which will be Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency authorised to prepare and supply aseptic medicines across a large area, ideally [over] several integrated care systems[11].”

Ladds said that hospitals will be purchasing the majority of their ready to administer doses of injectable products or standard products from either commercial suppliers or NHS hubs — or most likely a combination — adding that hospitals will only be making patient-specific products in local spoke facilities, where there are no standard batch produced products available[11].

“These hubs are going to provide the capacity to enable a ten-fold increase in production from 4 million to 40 million doses per year across England, and this will cover the growing demand that we’re seeing for chemotherapy and parenteral nutrition,” she said[11].

The DHSC has allocated £75m in funding between 2022 and 2025 for the initial five pathfinder hubs, the first of which will start to be built in 2023. Further capital will be required to support funding of additional hubs for a full national rollout, estimated to cost £275m.

Increasing workforce

The ‘NHS long-term workforce plan’, published in June 2023, committed to expanding training places for pharmacists by 29% to around 4,300 by 2029, as well as increasing the number of pharmacy technicians[12].

During the NHS Benchmarking Network webinar, Ladds said that, while there is a strong focus on the much-needed growth and development of the community pharmacy workforce within the plan, it does cover all pharmacy teams.

She highlighted that the plan includes optimising the development of the technical service workforce and increasing the scope of pharmacy technician practice.

“We’ve got a workforce working group within the programme, and they have identified priorities and developed action plans to achieve the workforce vision,” said Ladds.

“They’re looking at reviewing the education and training that’s available for this group of staff, assessing the fitness for purpose of that training and aiming for standardisation.”

In addition to the planned expansion of the pharmacy workforce, the Institute for Apprenticeships and Technical Education has said it is developing a new standard for the science manufacturing process apprenticeship. This will aim to provide a clearer pathway for science manufacturing technicians to work in aseptic units, improving the access and number of technicians available in the oncology workforce. The new apprenticeship standards are expected to be approved in 2024.

“Level 2 science manufacturing operatives and level 3 science manufacturing technicians are going to fill the technical services roles that used to be undertaken by pharmacy assistants, technicians and pharmacists,” says Foreman.

“But, obviously, these people are just being trained now. And it will take a while for sufficient numbers of them to come through the system to replace the staff that we’ve got at the moment,” she warns.

Future of SACT

Although there is light at the end of the tunnel in the form of the pathfinder hubs and the ‘NHS long-term workforce plan’, these interventions are unlikely to have much impact on the immediate service needs of oncology departments, which are currently in “crisis management” to maintain the SACT service.

To address this, in September 2023, the UK SACT board — an independent representative body for SACT services — published a set of short-term recommendations to relieve pressures on the aseptic service (see Box)[13].

Foreman calls for unity among oncology sectors. “We need to work collaboratively across our cancer pharmacy, nursing and medical teams; and partner with the commercial sector to address this problem head on so we can continue to provide excellent care to our patients,” she explains.

In response to the letter addressed to Barclay, a meeting with cancer care organisations and health minister Helen Whately was initially scheduled for July 2023 to discuss the recommendations. However, at the time of going to press in December 2023, this meeting had still not taken place, leaving the long-term future of NHS SACT and aseptic services in jeopardy.

Box: The UK SACT board’s recommendations

The recommendations provide specific advice to pharmacy, nursing and prescribers; and focus on five essential principles to increase workforce capacity by:

- Better utilisation of optimal scheduling;

- Pre-prescribing SACT;

- Timely authorisation of treatment;

- Timely blood reporting in advance where possible and where appropriate;

- Effective communication around dose changes, delays and missed appointments [13].

Advice for cancer pharmacy teams includes adopting national dose banding for appropriate SACT, using ready-made products, oral or subcutaneous administration and immunotherapy regimens with longest administration interval times, co-administration of lower risk products with SACT, as well as several other recommendations around policy and workflow optimisation [13].

“These are basically recommendations on how to prioritise chemotherapy, and how to keep your service going when you can’t do everything,” says Foreman.

“So, this is more like a crisis management type guideline, similar to what we had in COVID-19, when our capacity was reduced significantly,” she adds.

The UK SACT board stresses that while these recommendations are designed to provide ‘quick wins’ for oncology services, they should not reduce the efficacy of SACT treatment, affect patient outcomes or reduce patient or staff safety in any way[13].

- 1Duncombe R, Foreman E, Biliune J. A National Evaluation of Capacity in Intravenous Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy (IV SACT) Preparatory Services. BOPA Committee 2022. https://www.bopa.org.uk/resources/national-capacity-ivsact-evaluation/ (accessed December 2023)

- 2East and North Hertfordshire NHS Trust. Systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT) Patient Information Series PI02. Systemic anti-cancer therapy (SACT) – a patient’s guide. 2021. https://www.ljmc.org/pi_series/pi02_sact.pdf (accessed December 2023)

- 3National Disease Registration Service, NHS Digital. Systemic Anti-Cancer Therapy COVID-19 Dashboard. Cancer Data: SACT COVID-19 Dashboard. https://www.cancerdata.nhs.uk/covid-19/sact (accessed December 2023)

- 4Cancer Research UK. Cancer mortality statistics. Cancer Research UK. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/mortality#heading-Zero (accessed December 2023)

- 5National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Technology appraisal data: cancer appraisal recommendations. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-technology-appraisal-guidance/data/cancer-appraisal-recommendations (accessed December 2023)

- 6BOPA Committee . Letter to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care – Capacity challenges in oncology departments preventing the effective delivery of cancer drugs. BOPA. 2023. https://www.bopa.org.uk/letter-to-the-secretary-of-state-for-health-and-social-care-2023-capacity-challenges-in-oncology-departments-preventing-the-effective-delivery-of-cancer-drugs/ (accessed December 2023)

- 7Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Closed System Drug-Transfer Device (CSTD) Research. HAZARDOUS DRUG EXPOSURES IN HEALTHCARE. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hazdrug/CSTD.html (accessed December 2023)

- 8Carter of Coles LP. Transforming NHS Pharmacy Aseptic Services in England. Department of Health and Social Care. 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5f9afdbdd3bf7f1e405d9a23/aseptic-pharmacy.pdf (accessed 6 December 2023)

- 9Gov.UK. Find a contract. Contract Finger. https://www.contractsfinder.service.gov.uk/Search (accessed December 2023)

- 10The Royal College of Radiologists. The SACT capacity crisis in the NHS. Policy reports & initiatives. https://www.rcr.ac.uk/news-policy/policy-reports-initiatives/the-sact-capacity-crisis-in-the-nhs/#:~:text=The%20Royal%20College%20of%20Radiologists%20has%20produced%20an%20important%20briefing,therapies%20(SACT)%20to%20patients. (accessed December 2023)

- 11Ladds S. Update from the Hospital Pharmacy Modernisation Team. Webinar 2023.

- 12NHS England. NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. NHS England. 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan/ (accessed December 2023)

- 13UK SACT Board. General principles to support SACT aseptic capacity pressures. UK SACT Board – Publications. 2023. https://www.uksactboard.org/_files/ugd/638ee8_84eebe8e6ea04543bf08b43dd3e2b6d7.pdf (accessed December 2023)