Graham Turner / Alamy Stock Photo

Recommended thresholds for statin treatment to prevent cardiovascular (CV) events have encouraged wider access since the drugs were first introduced in the late 1980s.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) first recommended primary prevention with statins in those without pre-existing cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 2006, with the risk threshold lowered to 10% in 2014.

Current draft guidance from NICE, published on 12 January 2023, goes even further by recommending that statins can be considered for people without CVD, who have a ten-year risk of a CV event of less than 10% (measured by the QRISK3 calculator).

This change may mean an estimated 15 million more adults can now be considered for statin therapy. But what prompted this most recent change — and is it a good idea?

The case for:

Clinical efficacy

NICE says the evidence shows that if more people took statins at lower risks than 10%, fewer people would have a heart attack or stroke. Its calculations show that if 1,000 people with a 5% CV risk took a statin for 10 years, 20 people would avoid a CV episode (2% fewer events).

While the clinical evidence is not new, the risk–benefit calculation has changed. A review of independent patient data, published in The Lancet in August 2022, revealed that muscle pain was less common a side effect than previously thought, with results showing that only 1 in 15 reports of muscle pain by people taking statins could be attributed to the medicine.

Paul Wright, lead cardiac pharmacist at Bart’s Health Centre in London, says this change may not be such a big deal. “The 10% QRISK3 threshold is already relatively low. This is bringing it down that little bit further. [United States] guidelines have their risk at 7.5%. It’s that fine balance between risk and benefit and [the risk] has come down.”

Sir Nilesh Samani, medical director of the British Heart Foundation, says: “Heart attacks and strokes still kill more people prematurely than anything else, with high levels of cholesterol being a major risk factor.” He describes the NICE recommendation as “good news as it will help to reduce the number of heart attacks and strokes”.

Cost effectiveness

NICE’s analysis has concluded that statins were cost effective “for all people aged 40–80 years with a ten-year CVD-risk above 2%”, using the QRISK3 calculator.

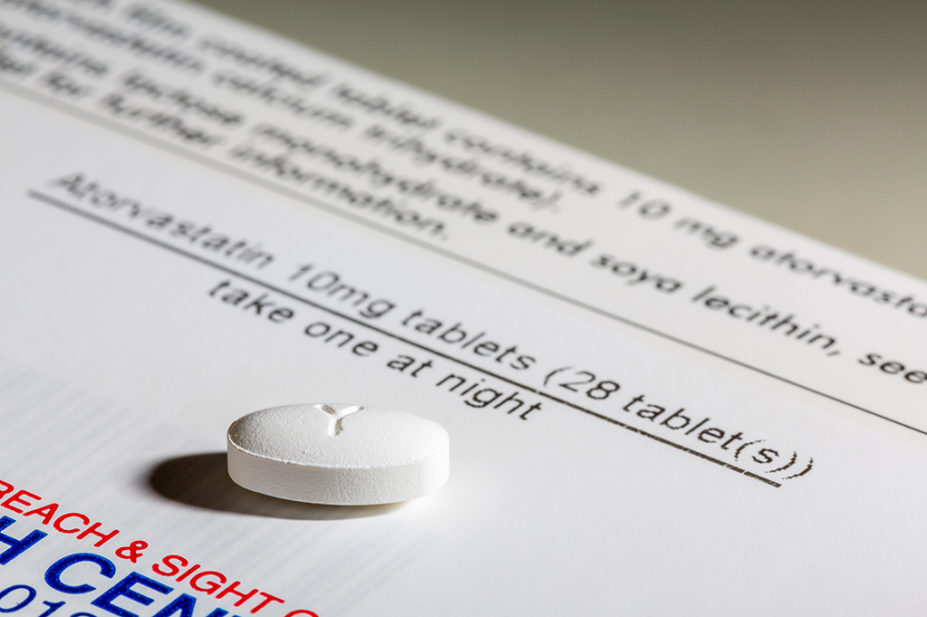

The analysis looked at drug costs (£12 annually for 12 months’ supply of atorvastatin 20mg, based on the September 2022 NHS Drug Tariff), annual healthcare visits and monitoring tests. However, NICE said “risk assessment costs were assumed common to everyone and not included”.

Individualised care and lifetime risk

The report says: “Given the clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence, the committee agreed that statins should not be restricted strictly for people with ten-year CVD risk scores over 10%.

“Younger people near the ten-year risk treatment threshold… will have a higher lifetime risk and potential to benefit from lipid lowering and should not be excluded from treatment,” the report says, adding that the new recommendation will “support individualised care”.

Rani Khatib, consultant pharmacist in cardiology at Leeds Teaching Hospitals, says that there is a debate between use of ten-year risk score and lifetime risk score. “If your risk over ten years is [reduced by] 2%, what does that mean lifelong?” he asks.

The case against:

Clinical efficacy

The risk of CVD for people below the 10% QRISK3 threshold does reduce with statins, but it is a case of diminishing returns. Reductions in CV events are much larger for people with 10% or 20% risk than for those with 5% risk.

NICE estimates that if 1,000 people with a 5% CVD risk took a statin for 10 years, 20 of those people would avoid a CVD episode. For people with a 10% and 20% risk, 40 and 70 of those people would avoid a CVD episode, respectively.

If the proposed guidelines were adopted, the UK would be a front runner (or an outlier) in opening access to statins for all adults. It is difficult to make direct comparisons between UK, US and European guidelines owing to varying CV risk calculators; however, both the European and US guidelines have a minimum risk level.

The European Society of Cardiology recommends treatment of CVD risk factors “in apparently healthy people… who are at very high CVD risk (SCORE2 7.5 or more [in those aged] under 50 [years], 10% or more [in those aged] 50–69 [years], 15% or more for aged 70 [years] and over”; whereas the US guidelines, authored by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, recommend initiation of statin therapy “in patients at borderline risk (5.0%–<7.5% ten-year Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease [ASCVD] risk)’ or intermediate risk (7.5%–20.0% risk)”.

While both sets of guidelines allow for statins at risk level lower than the 10% adopted by the UK previously, they do not suggest doing away with a minimum risk level altogether.

It could also be argued that work needs to be done to protect people at higher risk. Only 56% of people with a 20% CVD risk take statins, and only 45% of those with a 10% risk take them.

“The majority of the committee agreed that getting more people to start statins at the existing threshold was more important than lowering the threshold,” the NICE report says.

Wright agrees: “The gains to be made are among those at higher risk. The focus should be about getting higher risk patients — identifying them and having discussions and getting them on to treatment.”

Over-medicalisation is another fear, according to Jo Bateman, lead cardiology pharmacist at the Countess of Chester Hospital NHS Foundation Trust in Cheshire: “There is a risk of over-medicalising healthy people,” she says. “It would be better perhaps if more was invested into healthy living, diet, exercise etc., in those areas with high risk for CVD.”

Kamila Hawthorne, chair of the Royal College of GPs, concurs: “It is imperative that we do not overtreat and over-medicalise people, and that clinicians look beyond a risk calculator to measure someone’s risk of developing a certain condition — considering all the various factors potentially impacting on a patient’s health.”

Rani Khatib, consultant pharmacist in cardiology at Leeds Teaching Hospitals in Yorkshire, is unsure how much of an impact the change would have: “It is welcome, but is it a milestone? I’m not sure.”

“People need more guidance in deciding how would somebody with a risk less than 10% be a good candidate for statins,” he says. “Even when the risk is over 10%, they wonder should they start them on medication which is lifelong? It’s more complicated than it sounds. The patient has to be convinced to see the benefit and clinicians need to be confident.”

Other ways to reduce CV risk, such as blood pressure control or improved exercise and diet, may be equally worthy of attention before prescribing statins, although Paul Chrisp, director of the Centre for Guidelines at NICE, did say: “We are not advocating that statins are used alone. The draft guideline continues to say that it is only if lifestyle changes on their own are not sufficient, and that other risk factors such as hypertension are also managed, that people who are still at risk can be offered the opportunity to use a statin, if they want to.”

Cost effectiveness and opportunity costs

While NICE’s draft guideline has addressed the issue of cost effectiveness of providing treatment, it did not look at the potential opportunity costs of targeting lower-risk patients when so many at higher risk are not receiving optimal treatment. How will GPs — at a time of huge demand — be able to prioritise treating patients at higher risk while also considering offering treatment to those at lower risk?

The evidence review says that risk assessment costs (i.e. the costs of assessing whether a patient should take statins or not) were not included, as they were “assumed common to everyone” whether they were prescribed a statin or not. Yet increasing the population who might be eligible for statins seems likely to increase the numbers who need a risk assessment.

Risk assessment conversations about statins are not simple. Decisions are more finely balanced when patients are at lower risk, which could result in longer consultations as people try to reach a decision that is right for them. Add the possibility of more consultations if people have side effects or need dose titration or adjustment, annual checks to monitor the medication’s effects and discuss compliance with therapy, and these so-called ‘cheap’ pills start to get expensive.

Hawthorne says the guidance is adding unwelcome pressure: “GPs are currently under immense pressure of work, and the NICE guidelines — if eventually approved — will result in considerable addition to this workload.”

Bateman agrees: “Prevention is really important, and anything we can do to reduce the future burden of CV disease has to be a positive thing; however, from my experience looking at work across the region, the system is struggling to ensure patients with 10% CVD risk and the secondary prevention patients are managed properly.”

Wright says: “I think it is unlikely we will see a myriad of people coming in demanding or expecting [statin] therapy. The focus should be about getting higher risk patients — identifying them and having discussions and getting them on to treatment.”

Statement from NICE

NICE declined to comment further on the draft guidelines, or to allow its guideline development committee members to be interviewed; however, a statement says: “The draft guideline is still subject to public consultation and may therefore change as a result; the committee will have to consider feedback from stakeholders on this point (if there is any) and could put themselves in the position of being conflicted on it.”

Full details of the evidence review, draft guideline and information about how to respond to the public consultation can be found on the NICE website.

Our verdict

On 13 January 2023, the Daily Mail reported the change of guidelines with the startling headline: “Now anyone over 18 can get statins!”, but that looks unlikely to happen. The clinical and cost-effectiveness evidence is robust, but the real costs will be in identifying and assessing patients, which — considering the immense pressure currently on the NHS — might be a big ask.

Have your say

Is there any evidence we have missed? What do you think? Leave a comment below, or email us at: editor@pharmaceutical-journal.com