SEBASTIAN KAULITZKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this learning article, you should be able to:

- Differentiate between asplenia and hyposplenism and understand their causes and risk factors;

- Understand the normal role of the spleen and the consequences of loss in splenic function;

- Know how the condition is managed, including relevant advice on rescue antibodies and vaccinations.

The term ‘asplenia’ describes the absence of the spleen; this can be congenital (i.e. from birth) or acquired (i.e. surgical removal) and includes hyposplenism, which refers to the absence or reduction in splenic function[1]. Isolated congenital asplenia is extremely rare, although a French retrospective study has indicated that it may be more common than previously thought[2]. Certain chronic conditions can cause hyposplenism, such as sickle cell disease. Additionally, around 30% of adults with coeliac disease have reduced splenic function. With appropriate management of coeliac disease, hyposplenism can be reversed[1,3].

Patients with asplenia or hyposplenism are at increased risk of developing sepsis associated with encapsulated bacteria, namely Streptococcus pneumonia[3,4]. Although a variety of methods are available to screen for functional hyposplenism, there is currently no easily applied technique in routine practice to identify individuals who are at risk[5].

This article discusses the diagnosis and management of asplenia and hyposplenism. All healthcare providers should be aware of a patient’s absence of spleen or splenic function, as management will likely change; pharmacists and technicians working in hospital or GP settings should know the importance of early prescribing of antibiotics in unwell asplenic patients and when to escalate, as well as including vaccination history in medicines reconciliation processes.

Spleen

The spleen is located in the abdomen behind the 9th, 10th and 11th ribs[6]. Although there are variations in shape and size, the spleen is usually 12–20cm in length and weighs between 70–200g. Owing to the spleen’s location, it is difficult to feel unless it is abnormally large[7,8].

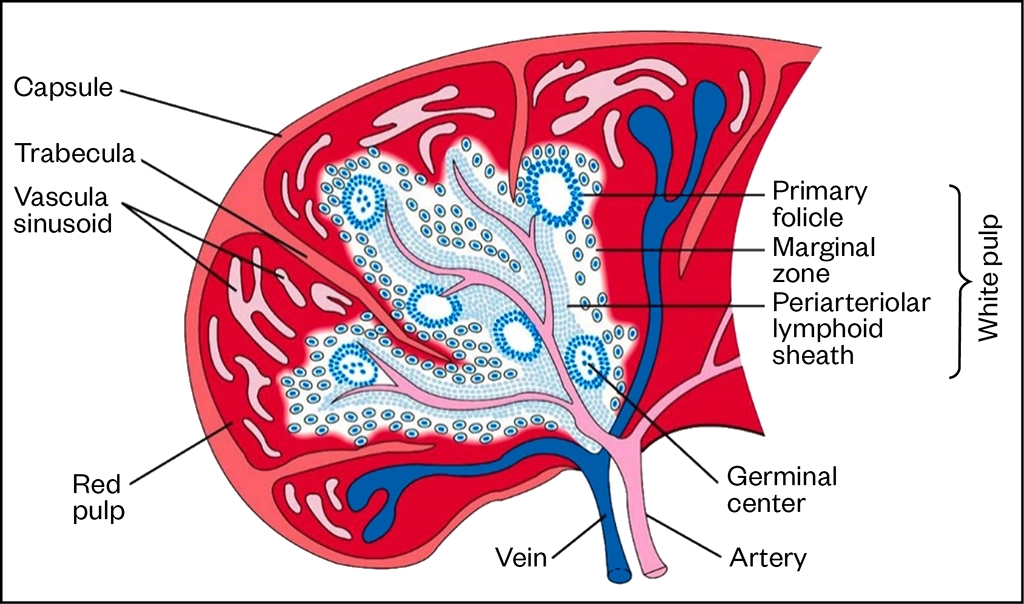

The spleen is made up of red and white pulp, which remove fatigued red blood cells, leucocytes and bacteria by phagocytosis via different pathways[9]. The red pulp makes up 75% of the spleen’s tissue and consists of a reticular framework that breaks down old red blood cells and haem[9]. The white pulp consists of lymphocytes, fibroblasts and the bodies largest aggregation of macrophages[9].

PIXOLOGICSTUDIO / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Adaptive immunity

The spleen is fundamental to the adaptive immune response, supporting both B- and T- cell activation; it is the only site in the body where an immune response can be initiated when the antigen is present in blood but absent from tissue. Memory B-cells are found most abundant here, making up 45% of the total B-cell population of the spleen[9–11].

An immune response can be mounted by the spleen in several ways, including:

- Exposure of foreign antigen to T-cells in the periarterial lymphatic sheath. In turn activating follicular B-cells to become antibody-producing plasma cells and travel into the wider systemic circulation;

- Contact between viral pathogen and follicular B-cells exposes antigen to nearby T-cells activating response;

- Foreign pathogen exposure to macrophages leading to subsequent exposure to B- and T-cells and activation/ production of plasma cells and antibodies[9].

A foetal spleen can produce all blood cells; however, in adults only lymphocytes are produced by the spleen. The spleen is also a store for blood and platelets that can be pushed into circulation when needed, such as in the event of trauma or blood loss[10,11].

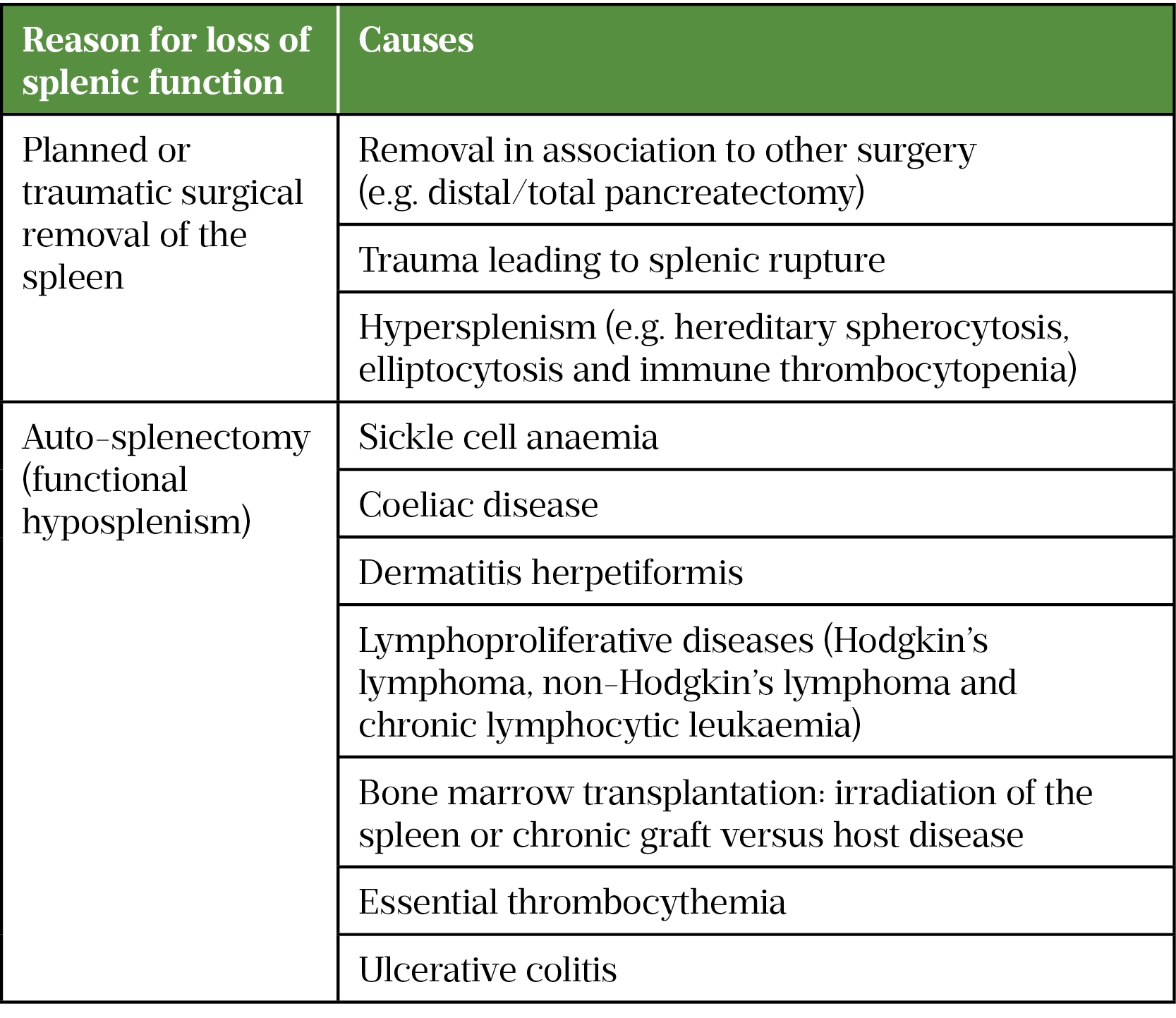

Causes of hyposplenism and asplenia

There are two ways that splenic function can be lost — planned or traumatic surgical removal — and auto-splenectomy referring to the physiological loss of splenic function associated with certain diseases, as detailed in Table 1[10,12].

*This list is not exhaustive

A damaged or ruptured spleen tends to result from abdominal trauma associated with traffic collisions or certain contact sports[13]. The spleen can rupture immediately but it has also been observed to occur weeks after the initial injury[13]. Patients are likely to complain of pain in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen located behind the ribs, which is generally tender to touch; they may also experience dizziness and tachycardia[13]. When lying down, a patient may complain of pain in the tip of their left shoulder, otherwise known as the Kehr’s sign, which results from irritation of the diaphragm, from a ruptured spleen, leading to nerve impulses in the phrenic nerve[14]. A ruptured spleen is a medical emergency, as it can lead to life-threatening bleeding, patients should be referred to a hospital emergency department if they have symptoms of this condition[13].

Splenomegaly — commonly referred to as an enlarged spleen — is a rare condition with an estimated prevalence of around 2% and can be caused by a number of pathophysiological mechanisms, including congestion associated with portal hypertension, infiltration of cells foreign to the spleen such as metastasis; immune factors such as sarcoidosis or rheumatoid arthritis; and cells with a neoplastic origin[6]. Symptoms tend to be non-specific abdominal pain, abdominal bloating and a reduction in appetite[6]. Treatment should target the underlying cause of splenomegaly, but additional caution should be advised to avoid rupture of the spleen, such as not partaking in contact sports[6].

Diagnosis

As part of the diagnostic process, the clinician can check blood films, specifically looking for Howell-Jolly bodies, which are nuclear remnants of erythrocytes that the spleen would usually filter[15]. Other imaging techniques, such as ultrasound, CT or MRI, may also be used[12]. Patients may have a palpable spleen with or without other findings of underlying illness; they may present with fatigue and/or anaemia, and bleeding or bruising associated with reduced platelet counts[13].

Management

Once a diagnosis of hyposplenism has been confirmed (whether it is congenital, surgical or functional) patients should receive appropriate vaccinations and prophylactic antibiotics as outlined below[3]. This includes those with intact spleens, as function is impaired, making them susceptible to infections.

It is important that patient’s medical records are updated to highlight their hyposplenic/asplenic status. Patients should also notify any new care providers as this may impact the management of other conditions[5]. An information leaflet and ‘alert card’ are also available for patients to carry with them[16].

Post-splenectomy infection is relatively uncommon, occurring in around 4% of patients without prophylaxis, but carries a high mortality rate, estimated at 50% within the first two years[12]. Those who are asplenic are at greater risk of encapsulated bacterial infections (e.g. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Neisseria meningitidis). The risk of infection can be minimised with appropriate education, timely vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis[12].

Vaccinations

For elective splenectomies, vaccinations should ideally be administered four to six weeks prior to admission[17]. Vaccination should never delay surgery and, in cases of emergency splenectomy or where vaccinations are not possible, they should be administered two weeks post-splenectomy[17]. All vaccinations are given via intramuscular injection; however, those with bleeding disorders should receive vaccinations via the deep subcutaneous route to reduce the risk of bleeding[3,18]. All patients should receive annual influenza vaccination owing to the increased risk of secondary bacterial infections[5].

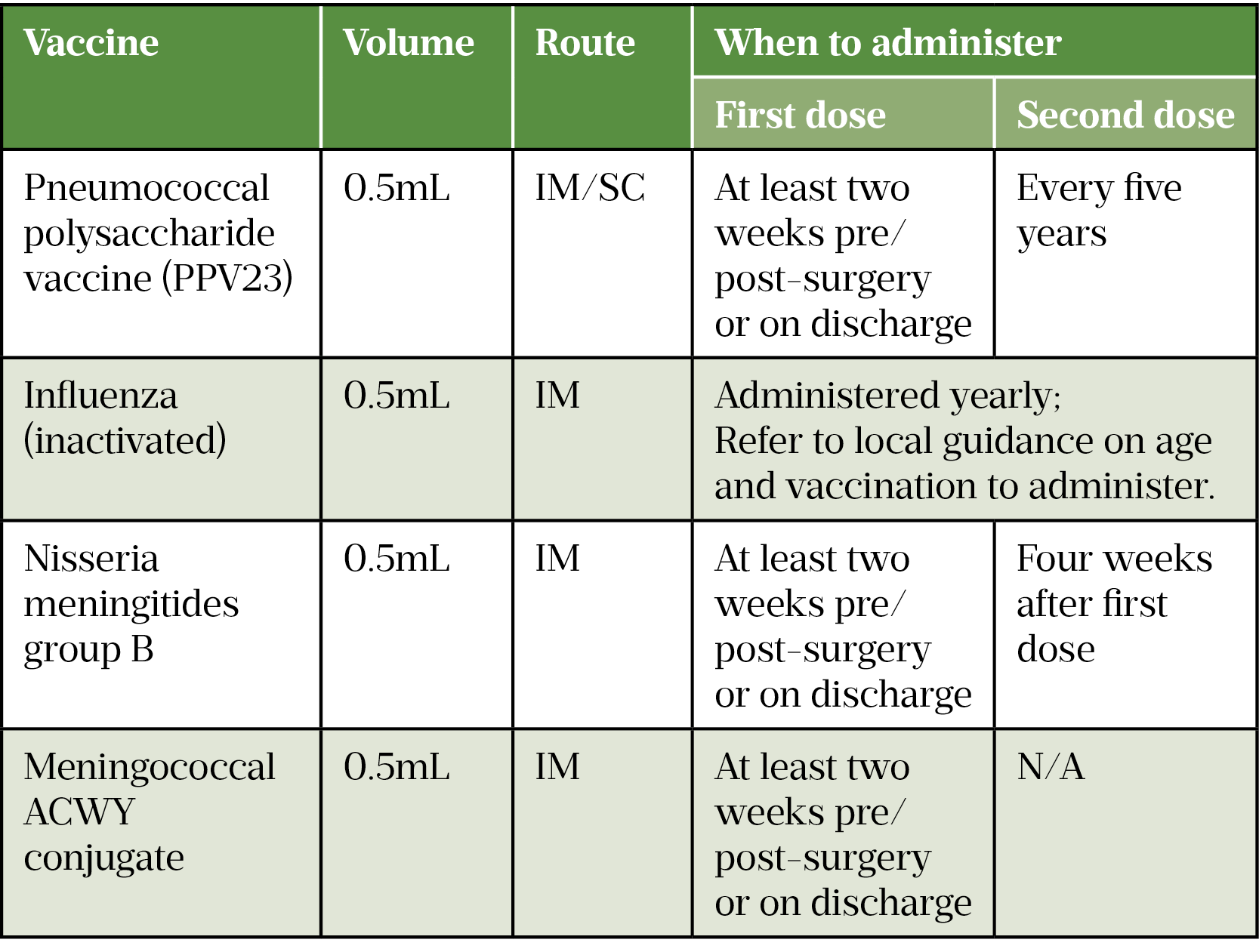

National guidance on vaccination schedules for patients with asplenia and splenic dysfunction is available via ‘The Green Book’, which is available online and is summarised in Table 2[3,19–23].

IM: intramuscular; SC: subcutaneous

There has recently been a move away from the requirement to vaccinate asplenic patients against haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) owing to the success of the childhood vaccination schedule resulting in extremely low risk of disease[3].

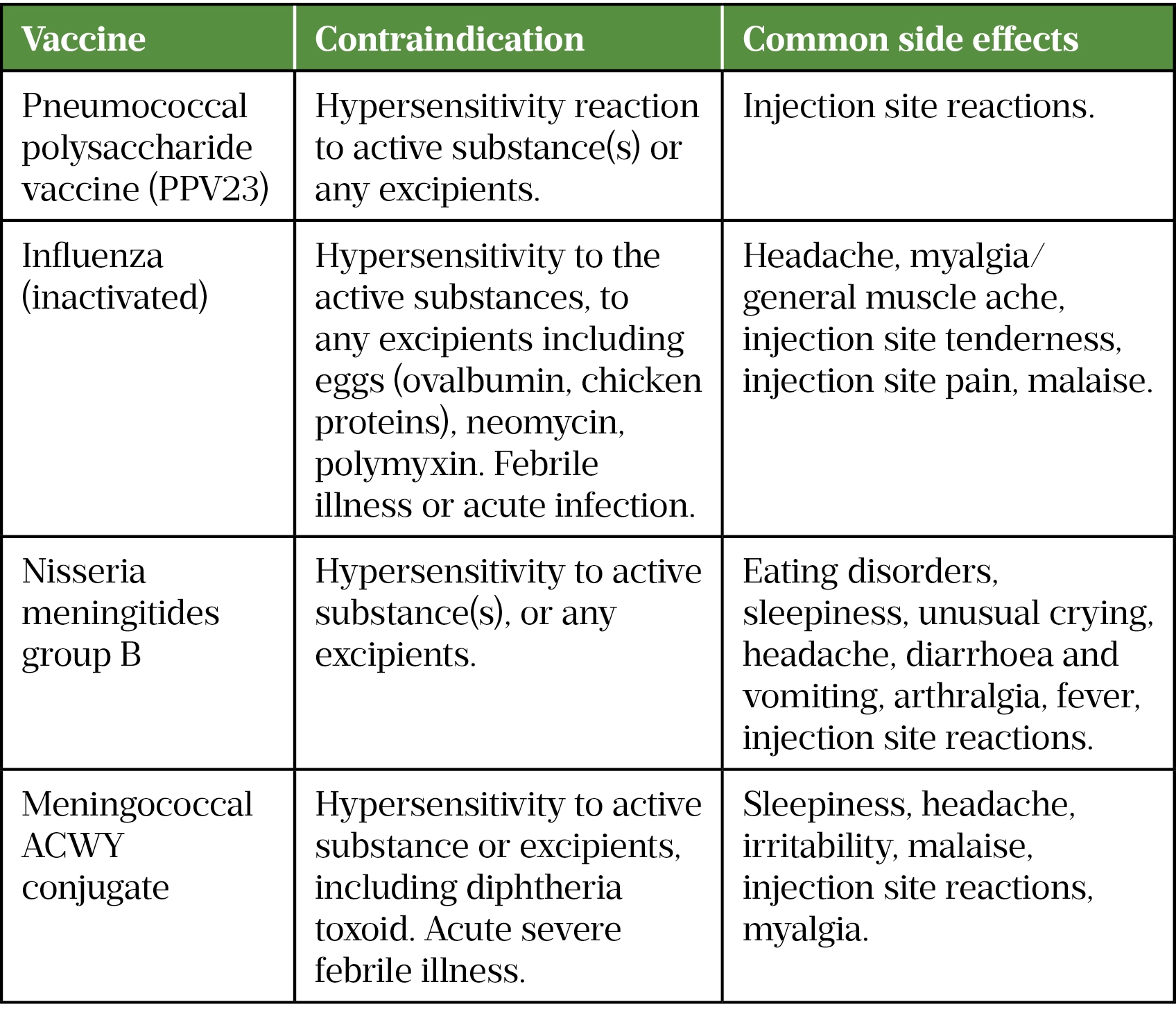

Contraindications do not always automatically result in a decision not to vaccinate — it should be done on a case-by-case basis. For some patients, the benefit from vaccination outweighs the risk, while in others alternative management would need to be considered such as long-term antibiotic prophylaxis alone[24]. Contraindications and common side effects from vaccines recommended to patients with splenic dysfunction can be seen in Table 3[19–23].

Antibiotics

The choice of antibiotic should consider the requirements to cover encapsulated bacteria, specifically Streptococcus pneumoniae, as the spleen naturally has a role in clearing these threats[25]. Prophylactic antibiotic recommendations are phenoxymethylpenicillin 250mg twice daily or an appropriate macrolide for penicillin allergic patients; guidelines may differ based on local antibiotic sensitivities[5,26].

Owing to the increased risk immediately post-operatively, patients are advised to take prophylactic antibiotics for several years. Currently, guidance varies, ideally antibiotics should be continued throughout the patient’s life, especially if there is high risk of pneumococcal infections. If antibiotic prophylaxis is discontinued, then the patient should have access to broad-spectrum antibiotics as outlined below[12].

Examples of patients who are at high risk of pneumococcal infections include[12]:

- Aged under 16 years or over 50 years;

- Poor response to pneumococcal vaccination;

- Previous invasive pneumococcal illness;

- Splenectomy for an underlying haematological malignancy (increased risk if immunosuppressed).

‘Rescue’ antibiotics

The term ‘rescue’ antibiotics refers to the accessibility of antibiotics to be taken as soon as symptoms of infection occur. All asplenic patients should have access to broad-spectrum antibiotics with appropriate education on usage and signs of infection (5). Patients should be advised to check the expiry date periodically and request replacement supplies from their GP should the course be used or expire. The prescriber should consider infective cause and/or cultures to tailor antibiotics as necessary to reduce risk of antibiotic resistances.

These antibiotics should be used when patients have the following signs and symptoms of infection, and seek medical advice as soon as is possible:

- Pyrexia (i.e. fever);

- Sore throat and/or cough;

- Severe headaches;

- Drowsiness or a rash;

- Abdominal pain;

- Redness or swelling around surgical site (post-operatively)[13].

Travelling abroad

Any patient planning to travel abroad should seek advice on prophylaxis for specific local infections and vaccinations; this is particularly important for those who are immunocompromised, as is the case for those without a functioning spleen[27].

Those who travel in certain parts of the world could be more susceptible to rare infections, such as babesiosis transmitted by tick bites, and malaria transmitted by mosquitoes. Additional advice should be offered, including: to wear clothes that reduce skin exposure, especially the legs; to seek medical advice if they become unwell; and to always travel with their ‘rescue’ antibiotics even if taking prophylaxis[28].

Accessibility to GPs or other travel clinics for advice is crucial to ensure travelling abroad is as safe as possible. There are a growing number of pharmacist prescribers offering services for travel clinics, meaning patients can be vaccinated and offered malaria prophylaxis without the need to see their GP.

Animal bites

Skin penetration risks increased complications of skin infections with Streptococcus and Staphylococcus species without timely management[28]. A patient’s likelihood of exposure to bugs or animals that may bite or sting should be discussed during counselling. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be used regardless of bite and patients are advised to seek medical advice should they become unwell after any bites. While in rural areas, patients should be advised to cover up to avoid tick bites[28].

Secondary (reactive) thrombocytosis

Secondary thrombocytosis refers to an unusually high platelet count owing to an underlying disease or event, such as acute blood loss or acute infection[29]. Platelet counts may be elevated post-splenectomy, this could be owing to blood loss during surgery, infection or inflammatory response[29]. Roughly 75% of patients without any prior diagnosed myeloproliferative disorders will develop thrombocytosis after a splenectomy[30].

Platelet counts usually peak between 7 and 20 days post-operatively with a well-documented thrombosis incidence of 5%[30]. Aspirin can be considered for patients whose platelet count exceeds 1,000,000 per microlitre to reduce risk of hyper-aggregation[12,29].

The pharmacist’s role

Post-operative recovery will reflect that of any surgical patient, including optimisation of fluid management, nutritional support, pain management, risk of venous thromboembolism, side effects of opioids and many other opportunities for pharmacist interventions. In the immediate post-operative period, pharmacists should ensure that medicines are appropriate, effective and safe for the patient.

Splenectomy counselling is extensive and should follow set guidance, as outlined in this article. Use the counselling checklist (see Box[5]) to stay on topic, along with an appropriate framework for consultations, such as the Calgary-Cambridge framework[31]. Repetition ensures the patient has grasped the main points, and it is important to allow ample opportunity for patients to ask questions. Patient and carer questions usually relate to antibiotic course length, vaccination schedules and immunity.

During the consultation, patients should be signposted to sources of information, which may include a splenectomy leaflet and websites (see ‘Useful resources‘). The patient’s local community pharmacies should be highlighted; they are likely to see the patient monthly for medication and can utilise the new medicines service and refer where appropriate. This level of interaction provides increased opportunity for patients to digest information and ask questions. Pharmacists should enquire about a patient’s ongoing antibiotic prophylaxis, vaccination schedule and offer advice on animal bites and travel vaccinations[5].

Counselling checklist for splenectomy patients

As a minimum, counselling points for splenectomy patients should include the following:

- Update of patient record and asplenic alert card (reminding them to highlight to any healthcare professional that they do not have a functioning spleen);

- Vaccination schedule (GP to administer boosters);

- Ongoing antibiotic prophylaxis (refer to ‘high-risk’ groups for life-long prophylaxis);

- Emergency antibiotics (should always be available — periodically check expiry date);

- Travelling abroad (vaccinations, malaria prophylaxis etc);

- Animal bites;

- Reiterate important points and offer time for questions;

- Signpost for future information.

Useful resources for patients:

Public Health England Leaflet and Card for patients

- 1Ashorobi D, Fernandez R. statpearls. Published Online First: 27 May 2021.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538171/

- 2Mahlaoui N, Minard-Colin V, Picard C, et al. Isolated Congenital Asplenia: A French Nationwide Retrospective Survey of 20 Cases. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2011;158:142-148.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.07.027

- 3Chapter 7: Immunisation of individuals with underlying medical conditions. The Green Book of Immunisation. 2020.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/857279/Greenbook_chapter_7_Immunsing_immunosupressed.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 4Ryan K, Cooper N, Eleftheriou P, et al. Guidance on shielding for Children and Adults with splenectomy or splenic dysfunction during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Society of Haematology. 2020.https://b-s-h.org.uk/media/18292/covid19-bsh-guidance-on-splenectomy-v2-final-6-may2020_.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 5Davies JM, Lewis MPN, Wimperis J, et al. Review of guidelines for the prevention and treatment of infection in patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen: Prepared on behalf of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology by a Working Party of the Haemato‐Oncology Task Force. British Journal of Haematology. 2011;155:308–17. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08843.x

- 6Chapman J, Bansal P, Goyal A, et al. statpearls. Published Online First: 11 August 2021.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430907/

- 7Ellis H. Clinical Anatomy – Applied Anatomy for Students and Junior Doctors . 11th ed. Oxford, UK: : Blackwell Publishing 2006.

- 8Marcovitch H. Spleen. In: Black’s Medical Dictionary. Maryland and Oxford, UK: : The Scarecrow Press 2006.

- 9Nigam Y, Knight J. The lymphatic system 3: its role in the immune system. Nurs Times 2020;116.https://cdn.ps.emap.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2020/11/201125-The-lymphatic-system-3-its-role-in-the-immune-system1.pdf

- 10Hume DA. The mononuclear phagocyte system. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2006;18:49–53. doi:10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.008

- 11Singh I. The Spleen. In: Textbook of Humar Histology (With Colour Atlas & Practical Guide. New Delhi: : Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers 2011.

- 12Tidy C. Splenectomy and Hyposplenism. Patient. 2020.https://patient.info/doctor/splenectomy-and-hyposplenism (accessed Nov 2021).

- 13Spleen problems and spleen removal. NHS. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/spleen-problems-and-spleen-removal/ (accessed Nov 2021).

- 14Savel H. A SIGN FOR PERIDIAPHRAGMATIC INFLAMMATION. JAMA. 1960;174:2162. doi:10.1001/jama.1960.03030170052023

- 15Scafidi J, Gupta V. statpearls. Published Online First: 27 April 2021.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557489/

- 16Splenectomy: leaflet and card. gov.uk. 2015.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/splenectomy-leaflet-and-card (accessed Nov 2021).

- 17Pneumococcal. In: The Green Book of Immunisation. UK government 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/857267/GB_Chapter_25_pneumococcal_January_2020.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 18Immunisation procedures. In: The Green Book of Immunisation. UK government 2012. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/147915/Green-Book-Chapter-4.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 19Summary of Product Characteristics for Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2017.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/1446 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 20Summary of Product Characteristics for Influenza vaccine (split virion, inactivated). Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2017.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27426 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 21Influenza. In: The Green Book of Immunisation. UK government 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/931139/Green_book_chapter_19_influenza_V7_OCT_2020.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 22Summary of Product Characteristics for Bexsero Meningococcal Group B vaccine for injection. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2017.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/28407 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 23Summary of Product Characteristics for Menveo Group A, C, W135 and Y conjugate vaccine. Electronic Medicines Compendium. 2015.https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/27347 (accessed Nov 2021).

- 24Contraindications and special considerations. In: The Green Book of Immunisation. UK government 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/655225/Greenbook_chapter_6.pdf (accessed Nov 2021).

- 25Sinwar PD. Overwhelming post splenectomy infection syndrome – Review study. International Journal of Surgery. 2014;12:1314–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.11.005

- 26Phenoxymethylpenicillin. BNF. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/phenoxymethylpenicillin.html (accessed Nov 2021).

- 27Immunocompromised Travellers. Fit for Travel, Public Health Scotland. https://www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/advice/general-travel-health-advice/immunocompromised-travellers (accessed Nov 2021).

- 28Rull G. Preventing Infection after Splenectomy. Patient. 2018.https://patient.info/digestive-health/spleen-pain/preventing-infection-after-splenectomy (accessed Nov 2021).

- 29Rokkam V, Kotagiri R. statpearls. Published Online First: 1 August 2021.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560810/

- 30Khan PN, Nair RJ, Olivares J, et al. Postsplenectomy Reactive Thrombocytosis. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings. 2009;22:9–12. doi:10.1080/08998280.2009.11928458

- 31Kurtz S, Silverman J, Benson J, et al. Marrying Content and Process in Clinical Method Teaching. Academic Medicine. 2003;78:802–9. doi:10.1097/00001888-200308000-00011