SEBASTIAN KAULITZKI/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

After reading this article, you should be able to:

- Recognise the common signs and symptoms associated with pernicious anaemia and vitamin B12 deficiency and those people most at risk;

- Understand the difficulties in gaining an accurate diagnosis of pernicious anaemia;

- Advise on the appropriate management of people with pernicious anaemia.

Introduction

Pernicious anaemia is an autoimmune condition that affects the stomach; however, it is the resultant vitamin B12 deficiency that causes the symptoms commonly associated with pernicious anaemia. It is characterised by inflammation and atrophy of the gastric mucosa resulting in reduced production of intrinsic factor and gastric acid. In many cases, auto-antibodies cause further damage by attacking gastric parietal cells and/or intrinsic factor. This is known as atrophic gastritis and results in ineffective transport and absorption of vitamin B12 from dietary sources[1]. Pernicious anaemia is a megaloblastic anaemia, because a lack of vitamin B12 — also commonly referred to as cobalamin — can cause abnormality in haematopoietic cell maturation[2].

Vitamin B12 is essential for cellular metabolism, particularly DNA synthesis, methylation and mitochondrial metabolism. Any deficiency can result in significant haematological, neurological and psychiatric manifestations which, if not identified and treated promptly, can be irreversible and cause significant morbidity and even mortality[3].

Vitamin B12 deficiency, including pernicious anaemia, is commonly encountered in primary care and pharmacists should be able to identify those people most at risk, know the common symptoms and ensure that patients receive adequate and personalised treatment. This article provides an overview of the diagnosis and management of pernicious anaemia, highlighting some of the challenges experienced by people living with this condition.

Prevalence

The incidence of pernicious anaemia is uncertain but international studies have estimated it to be 0.1% among the general population, rising to 1.9% in those aged over 60 years; pernicious anaemia may account for up to 20–50% of cases of vitamin B12 deficiency in adults[1,4]. This is likely to be an underestimate as obtaining a definitive diagnosis for the condition is challenging.

It is possible that some people who develop symptoms of a vitamin B12 deficiency with no clear causative factors may have ‘antibody-negative’ pernicious anaemia[2]. Pernicious anaemia is often considered to be a disease that only affects the older population; however, it can be diagnosed at any age and is more common in women[5]. There are strong familial links, with most patients having first-degree relatives with the disease, and recent genome-wide association studies have identified risk loci[6]. People with pernicious anaemia will typically have other autoimmune conditions, such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Grave’s disease and vitiligo[7].

Vitamin B12 deficiency and pernicious anaemia

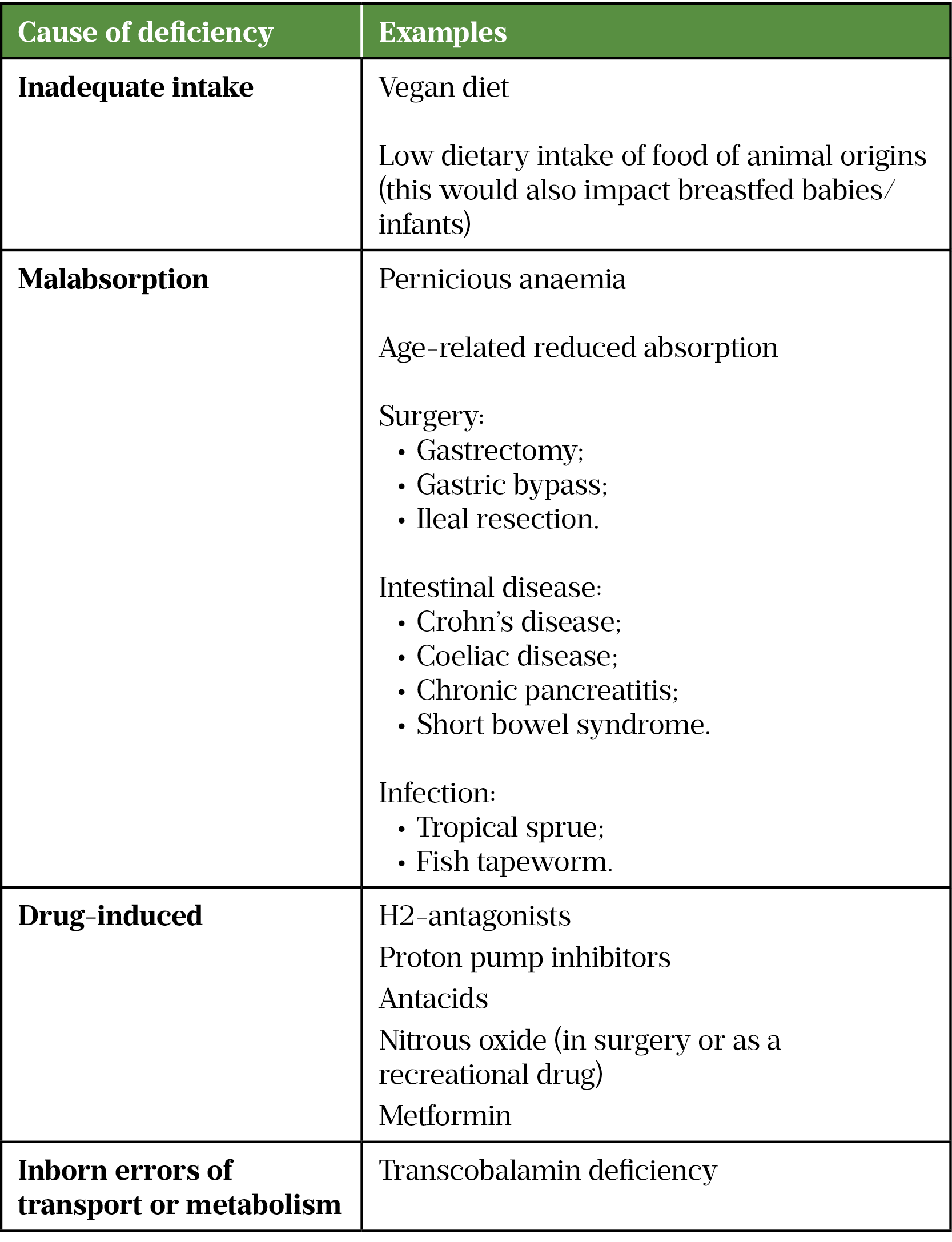

While pernicious anaemia accounts for a high proportion of cases of vitamin B12 deficiency, other causes include malabsorption or an inadequate dietary intake of vitamin B12 (see Table 1)[4,8–14]. While these would not cause pernicious anaemia, they could further deplete serum vitamin B12 levels and contribute towards the development of a symptomatic vitamin B12 deficiency.

Signs and symptoms

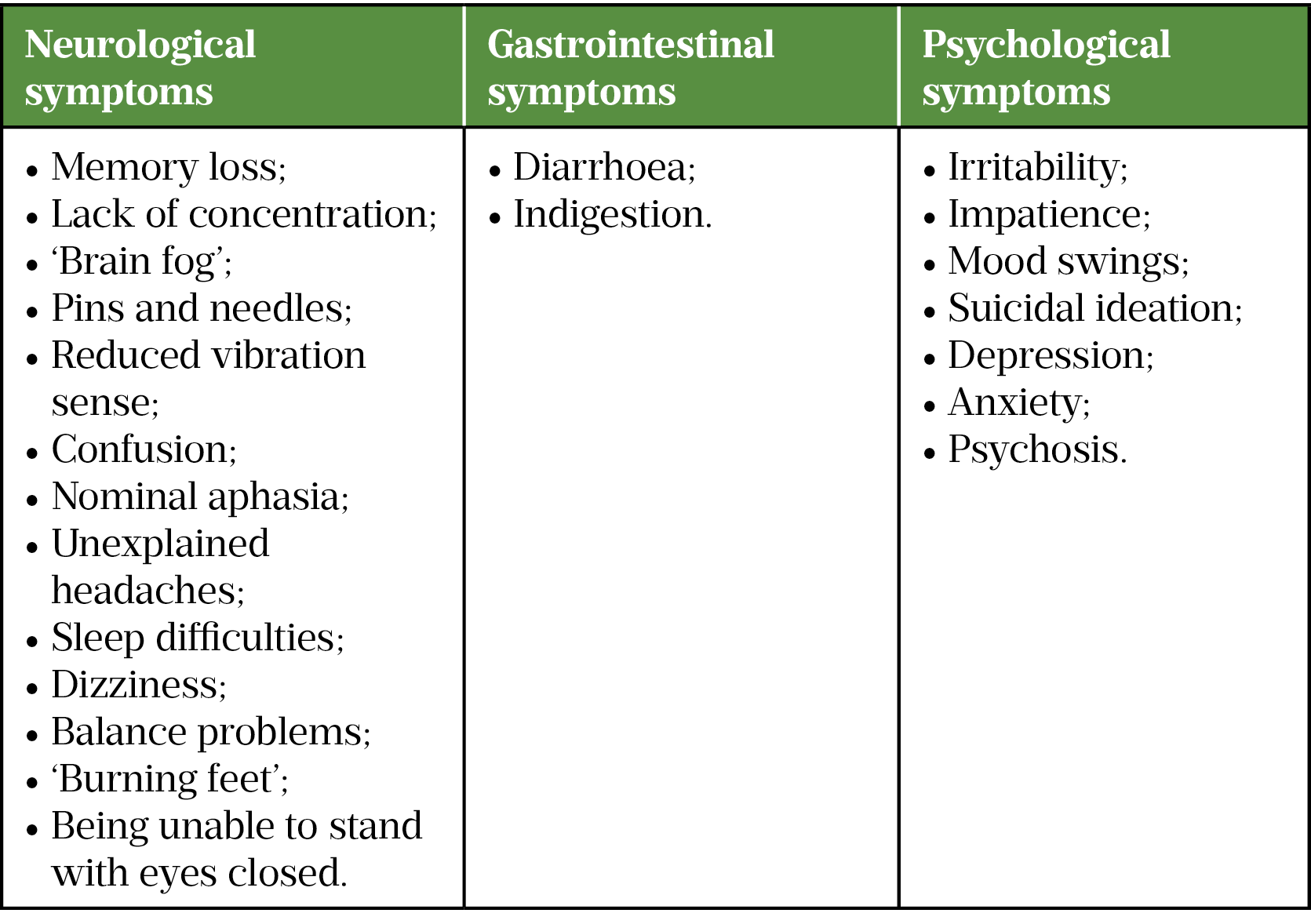

The presentation of pernicious anaemia typically follows a pattern of insidious symptoms and gradual onset. These symptoms are frequently misattributed to lifestyle and stage of life, such as work-related stress, pregnancy, menopause, ageing and dementia[15]. Fatigue is the most common symptom, often described as an unrelenting tiredness, which is not relieved by rest[15]. Neurological, gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms are also common along with glossitis (an inflamed and swollen tongue; see Table 2).

There is high variability in reported symptoms of pernicious anaemia: some patients report multiple symptoms that significantly impact their quality of life; others experience only minor issues. The symptoms experienced may also change as someone ages or goes through significant life events (e.g. pregnancy or the menopause).

These symptoms overlap with several other conditions, such as chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia and long COVID and, as a result, it is not always obvious when a referral for a serum vitamin B12 should be made. However, if a patient presents in primary care with a combination of these symptoms with no other obvious cause, or if they report any concerning neurological symptoms, they should be referred to their GP for testing[2].

Delays in diagnosis and subsequent initiation in treatment of pernicious anaemia have been shown to increase the risk of irreversible neurological damage involving both the central and peripheral nervous system, resulting in permanent symptoms, such as peripheral neuropathy, cognitive impairment and damage to the spinal cord (known as subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord)[9,16]. Other indicators include a family history of pernicious anaemia or other autoimmune conditions (such as type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, or Grave’s disease), or if the patient is taking metformin, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2 antagonists or has a history of nitrous oxide misuse[15].

Diagnosis

For patients presenting with clinical symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency, current guidelines recommend testing serum vitamin B12 levels alongside a full blood count and folate levels[2]. It is important that the patient avoids taking vitamin B12 supplements until after the serum test to ensure the accuracy of the test and establish a baseline.

Testing should also consider possible iron deficiency anaemia, macrocytosis, and take into account people on a vegan diet and individuals with a gastrointestinal disorder associated with a vitamin B12 deficiency (see Table 2)[17]. The term ‘pernicious anaemia’ itself can lead to confusion among clinicians, because there is not always an anaemia, macrocytosis or raised mean corpuscular volume at first presentation[2].

Diagnosis can be challenging because the serum test is not always conclusive. The current serum vitamin B12 assay has limited specificity and sensitivity and there is much debate on what level should be classed as normal, as there is not always correlation between serum level and the symptoms experienced by the patient[11,17]. Exact reference ranges also vary between individual laboratories, but generally a serum vitamin B12 of under 148pmol/L or 200ng/L is thought to indicate a deficiency[2]. If pernicious anaemia is suspected, a test for anti-intrinsic factor antibody should also be undertaken. However, the current available antibody assay has low sensitivity and studies have found that antibodies are only detectable in 40–60% of pernicious anaemia cases, so a negative test cannot categorically exclude pernicious anaemia[18,19].

Plasma methylmalonic acid (MMA) and plasma total homocysteine (tHcy) levels are also raised in vitamin B12 deficiency; however, these are not specific and may also be raised in other conditions, including renal disease. As such, these tests should be utilised in a supplementary context alongside the vitamin B12 level, full blood count and investigations to exclude other conditions[11].

Owing to the insidious onset of symptoms and limitations in diagnostic testing, many patients experience delays in diagnosis, with studies indicating that 38% of patients wait five years or more before diagnosis[20]. It is common for patients to be initially diagnosed with other conditions, such as depression, chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome before receiving their pernicious anaemia diagnosis[20]. As a result, these patients could be frequent visitors to their GP and community pharmacist during this time seeking symptom relief, over-the-counter ‘tonics’ or supplements and an identifiable cause for their symptoms.

Management

At the time of writing, the only guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pernicious anaemia currently available in the UK are the British Committee for the Standards in Haematology Guidelines published in 2014[2]. National Institute for Healthcare Excellence (NICE) guidance for the diagnosis and management of vitamin B12 deficiency, which will cover pernicious anaemia, is currently in development, due for publication in November 2023.

Hydroxocobalamin given by intra-muscular injection is recommended for the management of pernicious anaemia in the UK because this circumvents the atrophic damage in the stomach[21]. Cyanocobalamin injections are used in other countries, such as the United States. Treatment must be started promptly following diagnosis to reduce the risk of irreversible neurological symptoms (see Table 2)[17]. Loading doses are given initially, followed by regular maintenance injections as per the dosing schedule in the Box below.

Box: Hydroxocobalamin dosing schedule for the management of pernicious anaemia

If no neurological involvement:

Loading dose: 1,000 micrograms three times per week for two weeks

Maintenance dose: 1,000 micrograms every two to three months

If neurological involvement:

Loading dose: 1,000 micrograms every other day until no further improvement

Maintenance dose: 1,000 micrograms every two months

Injections are usually administered at a GP surgery, although some patients can be taught to self administer[22]. It is essential that hydroxocobalamin therapy is continued for life. Patients should be regularly asked about the impact of the treatment on their predominant symptoms and their quality of life, and the maintenance dosing interval adjusted as appropriate. Once treatment has been commenced there is no value in re-checking serum cobalamin levels; it is likely that these will be above the normal range and do not necessarily show any correlation with the symptoms experienced by patients[2,11].

Cyanocobalamin tablets are also available in the UK. While these are prescribed for some patients with pernicious anaemia, it should be noted that these are only licensed for vitamin B12 deficiency of dietary origin and not pernicious anaemia[21]. Many oral cyanocobalamin formulations are also available to purchase over the counter, in health food shops and online as dietary supplements. However, their efficacy is reduced in patients with pernicious anaemia. Oral formulations rely on passive absorption but, owing to the pathophysiology of the condition, patients with pernicious anaemia will only absorb around 1% of an orally administered dose[23].

While there is some limited evidence of the efficacy of 1,000 micrograms daily dosing of oral cyanocobalamin, this is mainly based on the correction of serum vitamin B12 levels, rather than any impact on clinical signs and symptoms[24]. Caution is advised regarding the use of oral supplements in patients with pernicious anaemia, meaning that careful monitoring of symptoms would be required, and is not generally advised in patients with neurological symptoms, owing to limited efficacy and potentially serious impact of permanent neurological damage[25]. Intramuscular treatment should be re-instated at the first sign of a recurrence of neurological symptoms in a patient previously changed to an oral formulation.

Other formulations are available to purchase in pharmacies, health food shops and online sources, including buccal tablets, sprays and patches. These may contain hydroxocobalamin or other cobalamins, such as methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin, and are classed as supplements for use in people with dietary deficiencies, such as those on vegan diets. Some patients with pernicious anaemia use these in addition to their prescribed injections if adequate symptom relief is not sustained throughout their maintenance treatment interval. Treatment with vitamin B12 is thought to be safe, with long-term studies noting that there is no increased risk of mortality associated with high serum vitamin B12 concentrations[26].

It is also important to ensure adequate folate levels through supplementation, if appropriate, once vitamin B12 supplementation has been commenced to avoid precipitating subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord[2].

Challenges in effective management

While treatment with hydroxocobalamin is effective in most cases, some patients may continue to experience symptoms (particularly neurological symptoms and fatigue)[27]. Responses to a 2014 survey of 889 patients with pernicious anaemia revealed that up to 92% of patients notice a return of their symptoms before their next dose is due[28]. Some physicians will authorise patients to receive injections more frequently than the recommended regimen (see Box), but many will not.

In this same survey, 44% of patients that perceived their treatment to be inadequate purchased their own additional supplementation, which in some cases included purchasing injections online from other countries, such as Germany, where hydroxocobalamin it is available over the counter and self-administered.

It is also important to be aware that patients may visit private providers for additional injections, including aesthetic practitioners and sometimes unregulated ‘IV vitamin drip clinics’[29].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many patients experienced challenges in accessing their regular injections, with some GP practices stopping injections temporarily or changing patients to oral tablets, resulting in significant anxiety and a return of symptoms for some patients[30]. Subsequently, some practices have not reverted back to injections.

Patients may visit their community pharmacy seeking advice regarding purchasing additional supplementation or ask how they can access syringes, needles and sharps bins to facilitate self-administration of injections, if they are not finding adequate symptom relief from their prescribed regimen or find their symptoms return before their next dose is due. They may also seek reassurance if their GP practice has altered or stopped their usual maintenance therapy.

Pharmacy staff should advise patients to keep a diary of their symptoms and to speak to their GP about any potential change to their treatment schedule. Information and support for both patients and healthcare professionals is available from the Pernicious Anaemia Society.

Diagnosis and management of pernicious anaemia is currently imprecise, with many unanswered questions and a lack of consistency in practise[31]. Research is currently in progress to address some of these issues and, as mentioned, NICE guidelines for the diagnosis and management of vitamin B12 deficiency are in development. These changes will support the provision of more consistent, person-centred and individualised management of pernicious anaemia by all members of the healthcare team, including pharmacists, working in partnership with patients.

Disclosures

Nicola Ward undertakes unpaid advisory work for the Pernicious Anaemia Society, and has presented at their annual conferences. She was a trustee between 2018 and 2020. She is a member of CluB12, an international research network of clinicians and researchers in vitamin B12.

Martyn Hooper is the executive chair of the Pernicious Anaemia Society. He has published three books on pernicious anaemia and contributed to several publications providing expert patient experience.

- 1Toh B-H, van Driel IR, Gleeson PA. Pernicious Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1441–8. doi:10.1056/nejm199711133372007

- 2Devalia V, Hamilton M, Molloy A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cobalamin and folate disorder. British Society for Haemotology. 2014.https://b-s-h.org.uk/guidelines/guidelines/diagnosis-of-b12-and-folate-deficiency/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 3Stabler SP. Vitamin B12Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:149–60. doi:10.1056/nejmcp1113996

- 4Loukili NH, Noel E, Blaison G, et al. Données actuelles sur la maladie de Biermer. À propos d’une étude rétrospective de 49 observations. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2004;25:556–61. doi:10.1016/j.revmed.2004.03.008

- 5Lahner E, Dilaghi E, Cingolani S, et al. Gender-sex differences in autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Translational Research. 2022. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2022.04.006

- 6Laisk T, Lepamets M, Koel M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five risk loci for pernicious anemia. Nat Commun. 2021;12. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-24051-6

- 7Michels AW, Gottlieb PA. Autoimmune polyglandular syndromes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2010;6:270–7. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2010.40

- 8Bakaloudi DR, Halloran A, Rippin HL, et al. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Clinical Nutrition. 2021;40:3503–21. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.035

- 9Andrès E, Affenberger S, Vinzio S, et al. Food-cobalamin malabsorption in elderly patients: Clinical manifestations and treatment. The American Journal of Medicine. 2005;118:1154–9. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.02.026

- 10Kornerup LS, Hvas CL, Abild CB, et al. Early changes in vitamin B12 uptake and biomarker status following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Clinical Nutrition. 2019;38:906–11. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2018.02.007

- 11Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood. 2017;129:2603–11. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-10-569186

- 12Miller JW. Proton Pump Inhibitors, H2-Receptor Antagonists, Metformin, and Vitamin B-12 Deficiency: Clinical Implications. Advances in Nutrition. 2018;9:511S-518S. doi:10.1093/advances/nmy023

- 13Oussalah A, Julien M, Levy J, et al. Global Burden Related to Nitrous Oxide Exposure in Medical and Recreational Settings: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis. JCM. 2019;8:551. doi:10.3390/jcm8040551

- 14Kibirige D, Mwebaze R. Vitamin B12 deficiency among patients with diabetes mellitus: is routine screening and supplementation justified? J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2013;12. doi:10.1186/2251-6581-12-17

- 15Hooper M. What you need to know about Pernicious Anaemia and Vitamin B12 Deficiency. Hammersmith Health Books 2015. https://www.hammersmithbooks.co.uk/product/what-you-really-need-to-know-about-vitamin-b12-deficiency-and-pernicious-anaemia/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 16Lindenbaum J, Healton EB, Savage DG, et al. Neuropsychiatric Disorders Caused by Cobalamin Deficiency in the Absence of Anemia or Macrocytosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1720–8. doi:10.1056/nejm198806303182604

- 17Hunt A, Harrington D, Robinson S. Vitamin B12 deficiency. BMJ. 2014;349:g5226–g5226. doi:10.1136/bmj.g5226

- 18Berth M, Bonroy C, Guerti K, et al. Comparison of five commercially available ELISA kits for the determination of intrinsic factor antibodies in a vitamin B12 deficient adult population. Int. Jnl. Lab. Hem. 2015;38:e12–4. doi:10.1111/ijlh.12449

- 19CARMEL R. Reassessment of the relative prevalences of antibodies to gastric parietal cell and to intrinsic factor in patients with pernicious anaemia: influence of patient age and race. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 1992;89:74–7. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06880.x

- 20Hooper M, Hudson P, Porter F, et al. Patient journeys: diagnosis and treatment of pernicious anaemia. Br J Nurs. 2014;23:376–81. doi:10.12968/bjon.2014.23.7.376

- 21BNF 83. London: : Pharmaceutical Press 2022. https://bnf.nice.org.uk (accessed Jul 2022).

- 22Warren J. Pernicious anaemia: self-administration of hydroxocobalamin in the covid-19 crisis. BMJ. 2020;:m2380. doi:10.1136/bmj.m2380

- 23Berlin H, Berlin R, Brante G. ORAL TREATMENT OF PERNICIOUS ANEMIA WITH HIGH DOSES OF VITAMIN B12 WITHOUT INTRINSIC FACTOR. Acta Medica Scandinavica. 2009;184:247–58. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1968.tb02452.x

- 24Wang H, Li L, Qin LL, et al. Oral vitamin B12 versus intramuscular vitamin B12 for vitamin B12 deficiency. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd004655.pub3

- 25Carmel R. How I treat cobalamin (vitamin B12) deficiency. Blood. 2008;112:2214–21. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-03-040253

- 26Wolffenbuttel BHR, Heiner-Fokkema MR, Green R, et al. Relationship between serum B12 concentrations and mortality: experience in NHANES. BMC Med. 2020;18. doi:10.1186/s12916-020-01771-y

- 27McCaddon A. Vitamin B12 in neurology and ageing; Clinical and genetic aspects. Biochimie. 2013;95:1066–76. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2012.11.017

- 28Ward N, Hooper M. How collaborating with patients led to improved management of pernicious anaemia. Rx Magazine. 2019.https://rxmagazine.org/how-collaborating-with-patients-led-to-improved-management-of-pernicious-anaemia/ (accessed Jul 2022).

- 29Dayal S, Kolasa KM. Consumer Intravenous Vitamin Therapy : Wellness Boost or Toxicity Threat? Nutr Today 2021;56:234–8.https://alliedhealth.ceconnection.com/ovidfiles/00017285-202109000-00004.pdf

- 30Seage CH, Semedo L. How Do Patients Receiving Prescribed B12 Injections for the Treatment of PA Perceive Changes in Treatment During the COVID-19 Pandemic? A UK-Based Survey Study. Journal of Patient Experience. 2021;8:237437352199884. doi:10.1177/2374373521998842

- 31Pernicious Anaemia Top 10. Pernicious Anaemia Priority Setting Partnership. https://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/pernicious-anaemia/top-10-priorities.htm (accessed Jul 2022).